Lost film

A lost film is a feature or short film that is no longer known to exist in any studio archives, private collections, or public archives, such as the U.S. Library of Congress.[1]

Conditions

During most of the 20th century, U.S. copyright law required at least one copy of every American film to be deposited at the Library of Congress at the time of copyright registration, but the Librarian of Congress was not required to retain those copies: "Under the provisions of the act of March 4, 1909, authority is granted for the return to the claimant of copyright of such copyright deposits as are not required by the Library."[2] Of American silent films, far more have been lost than have survived, and of American sound films made from 1927 to 1950, perhaps half have been lost.[3]

The phrase "lost film" can also be used in a literal sense for instances where footage of deleted scenes, unedited, and alternative versions of feature films are known to have been created, but can no longer be accounted for. Sometimes, a copy of a lost film is rediscovered. A film that has not been recovered in its entirety is called a partially lost film. For example, the 1922 film Sherlock Holmes was eventually discovered, but some of the footage is still missing.

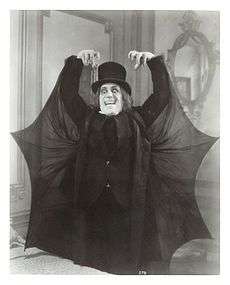

Stills

Most film studios routinely had a still photographer with a large-format camera working on the set during production, taking pictures for potential publicity use.[4] The high-quality photographic paper prints that resulted — some produced in quantity for display use by theaters, others in smaller numbers for distribution to newspapers and magazines — have preserved imagery from many otherwise lost films. In some cases, such as London After Midnight, the surviving coverage is so extensive that an entire lost film can be reconstructed scene by scene from still photographs. Stills have been used to stand in for missing footage when making new preservation prints of partially lost films, for example the Gloria Swanson picture Sadie Thompson (1928).

Reasons for film loss

.jpg)

Most lost films are from the silent film and early talkie era, from about 1894 to 1930.[6] Martin Scorsese's Film Foundation estimates that more than 90% of American films made before 1929 are lost,[7] and the Library of Congress estimates that 75% of all silent films are lost forever.[8]

The largest cause of silent film loss was intentional destruction. Before the era of television (and home video) films were viewed as having little future value when their theatrical runs ended. Similarly, silent films were perceived as worthless after the end of the silent era. Film preservationist Robert A. Harris has said, "Most of the early films did not survive because of wholesale junking by the studios. There was no thought of ever saving these films. They simply needed vault space and the materials were expensive to house."[9] Meanwhile, the studios could earn money by recycling the film for their silver content. Many Technicolor two-color negatives from the 1920s and 1930s were thrown out when studios simply refused to reclaim their films, still being held by Technicolor in its vaults. Some used prints were sold to scrap dealers and ultimately cut up into short segments for use with small, hand-cranked 35 mm movie projectors, which were sold as a toy for showing brief excerpts from Hollywood movies at home.

In some cases the destruction was proactive. Following a series of trials (which ultimately acquitted him) for the alleged rape and killing of actress Virginia Rappe in 1921, silent film star Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle's name had become so toxic that studios engaged in a program of determined destruction of films in which he had starred.[10]

Many other early motion pictures are lost because the nitrate film used for nearly all 35 mm negatives and prints made before 1952 is highly flammable. When in very badly deteriorated condition and improperly stored (e.g. in a sun-baked shed), nitrate film can spontaneously combust. Fires have destroyed entire archives of films. For example, a storage vault fire in 1937 destroyed all the original negatives of pre-1935 films made by Fox Pictures.[11] The 1965 MGM vault fire resulted in the loss of hundreds more silent films and early talkies.

Nitrate film is chemically unstable and over time can decay into a sticky mass or a powder akin to gunpowder. This process can be very unpredictable: some nitrate film from the 1890s is still in good condition today, while some much later nitrate had to be scrapped as unsalvageable when it was barely 20 years old. Much depends on the environment in which it is stored. Ideal conditions of low temperature, low humidity, and adequate ventilation can preserve nitrate film for centuries, but in practice, the storage conditions were usually far from ideal. When a film on nitrate base is said to have been "preserved", this almost always means simply that it has been copied onto safety film or, more recently, digitized; both methods result in some loss of quality.

Eastman Kodak introduced a nonflammable 35 mm film stock in spring 1909. However, the plasticizers used to make the film flexible evaporated too quickly, making the film dry and brittle, causing splices to part and perforations to tear. By 1911, the major American film studios were back to using nitrate stock.[12] "Safety film" was relegated to sub-35 mm formats such as 16 mm and 8 mm until improvements were made in the late 1940s.

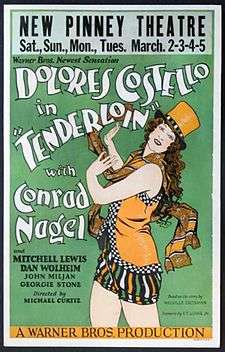

Some pre-1931 sound films made by Warner Bros. and First National have been lost because they used a sound-on-disc system with a separate soundtrack on special phonograph records. If some of a film's soundtrack discs could not be found in the 1950s when 16 mm sound-on-film reduction prints of early "talkies" were being made for inclusion in television syndication packages, that film's chances of survival plummeted: many sound-on-disc films have survived only by way of those 16 mm prints.

As a consequence of this widespread lack of care, the work of many early filmmakers and performers has made its way to the present only in fragmentary form. A high-profile example is the case of Theda Bara; one of the best-known actresses of the early silent era, she made 40 films, but only six are now known to exist. Clara Bow was equally celebrated in her heyday, but 20 of her 57 films are completely lost, and another five are incomplete.[13] Once-popular stage actresses who made the jump to silent films, such as Pauline Frederick and Elsie Ferguson, are now largely forgotten with little left of their film performances; fewer than 10 movies exist from Frederick's work from 1915–28, and Ferguson has just two surviving films: one from 1919 and her only talkie from 1930.

All of the film performances of the stage actress and Bara rival Valeska Suratt have been lost. William Farnum, a Fox player like Bara and Suratt, was one of the early screen's big Western actors, rivalling the likes of William S. Hart, Tom Mix, and Harry Carey. However, today only three of his Fox films are extant. Others, such as Francis X. Bushman and William Desmond, had numerous film credits, but films made in their heyday are missing due to junking, neglect, or studios becoming defunct. Nevertheless, unlike Suratt and Bara, these men continued working into the sound era and even on television, so their later performances can be viewed.

There are occasional exceptions. Almost all of the films made by Charlie Chaplin have survived, as well as extensive amounts of unused footage dating back to 1916. The exceptions are A Woman of the Sea (which he destroyed himself as a tax write-off) and one of his early Keystone films, Her Friend the Bandit (see Unknown Chaplin). The filmography of D. W. Griffith is nearly complete, as many of his early Biograph films were deposited by the company in paper print form at the Library of Congress. Many of Griffith's feature-film works of the 1910s and 1920s found their way to the film collection at the Museum of Modern Art in the 1930s, and were preserved under the auspices of curator Iris Barry. Mary Pickford's filmography is nearly complete; her early years were spent with Griffith, and she gained control of her own productions in the late 1910s and early 1920s. She also backtracked to as many of her Zukor-controlled early Famous Players films as were salvageable. Stars such as Chaplin and Douglas Fairbanks enjoyed stupendous popularity, and their films were reissued over and over throughout the silent era, meaning prints of their films were likely to surface decades later. Pickford, Chaplin, Harold Lloyd, and Cecil B. DeMille were early champions of film preservation, although Lloyd lost a good number of his silent works in a vault fire in the early 1940s.

In March 2019, the National Film Archive of India reported that 31,000 of its film reels had been lost or destroyed.[14]

Later lost films

An improved 35 mm safety film was introduced in 1949. Since safety film is much more stable than nitrate film, comparatively few films were lost after about 1950. However, color fading of certain color stocks and vinegar syndrome threaten the preservation of films made since about this time.

Most mainstream movies from the 1950s onwards survive today, but several early pornographic films and some B movies are lost. In most cases, these obscure films go unnoticed and unknown, but some films by noted cult directors have been lost, as well:

- Several films by Kenneth Anger from across his career have been lost for a variety of reasons.

- The 1972 film The Undergraduate, directed by Ed Wood, has been lost. His 1971 film Necromania was believed lost for years, until an edited version resurfaced at a yard sale in 1992, followed by a complete unedited print in 2001.[15] A complete print of the previously lost Wood pornographic film The Young Marrieds was discovered in 2004. His 1970 film Take It Out in Trade was thought to exist only in fragments without sound, released on home video in 1995 as Take It Out in Trade: The Outtakes, until the release of a scanned 16mm theatrical print on Blu-ray Disc in 2018.

- The Noble Experiment (1955), the first feature film from director/writer Tom Graeff (in which he played a misunderstood genius scientist) was considered lost for many years, until it was found by Elle Schneider during the production of The Boy from Out of This World, a documentary about Graeff.

- Most of the early films of Andy Milligan are considered lost.

- Many short sponsored films—films made for educational, training, or religious purposes—from the 1940s through the 1970s are also lost, as they were thought of as disposable or upgradable.

- Some of the first roles of Jackie Chan and Sammo Hung, including Big and Little Wong Tin Bar, were considered lost until their discovery and re-release in 2016.

- The first three films of noted Finnish melodrama actor and director Teuvo Tulio were lost, along with several other films that were of interest at least for historians of Finnish cinema, when the film depository of the company Adams Filmi burned down in Helsinki in 1959.

- Sometimes, only certain aspects of films may be lost. Early color films such as The Mysterious Island (The Boy from Out of This World, 1929) and The Show of Shows (John G. Adolfi, 1929) exist only partially or not at all in color, because the copies that were made of the film which still exist were created on black-and-white stock. (See List of early color feature films.)

- Two three-dimensional films from 1954, Top Banana and Southwest Passage, exist only in their flat form because only one print, made for either the left or right eye, exists.

Lost film soundtracks

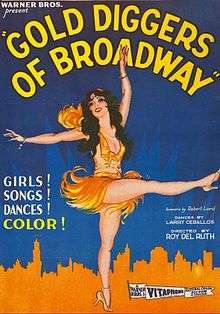

Some films produced from 1926–31 using the Vitaphone sound-on-disc system, in which the soundtrack is separate from the film, are now considered lost because the soundtrack discs were lost or destroyed, while the picture elements survive. Conversely, and more commonly, some early sound films survive only as sets of soundtrack discs, with the picture elements completely missing (e.g. The Man from Blankley's (1930), starring John Barrymore) or surviving only in fragmentary form (e.g. Gold Diggers of Broadway (1929) and The Rogue Song (1930), two highly popular and profitable early musicals in two-color Technicolor).

Many stereophonic soundtracks from the early to mid-1950s that were either played in interlock on a 35 mm fullcoat magnetic reel or single-strip magnetic film (such as Fox's four-track magnetic, which became the standard of mag stereophonic sound) are now lost. Films such as House of Wax, The Caddy, The War of the Worlds, The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T, and From Here to Eternity that were originally available with 3-track, magnetic sound are now available only with a monophonic optical soundtrack. The chemistry behind adhering magnetic particles to the tri-acetate film base eventually caused the autocatalytic breakdown of the film (vinegar syndrome). As long as studios had a monaural optical negative that could be printed, studio executives felt no need to preserve the stereophonic versions of the soundtracks.

List of lost films

List of incomplete or partially lost films

Rediscovered films

Occasionally, prints of films considered lost have been rediscovered. An example is the 1910 version of Frankenstein which was believed lost for decades until the existence of a print (which had been in the hands of an unwitting collector for years) was discovered in the 1970s. A print of Richard III (1912) was found in 1996 and restored by the American Film Institute. In 2013, an early Mary Pickford film, Their First Misunderstanding, notable for being the first film in which she was credited by name, was found in a New Hampshire barn and donated to Keene State College.[16]

Beyond the Rocks (1922), with Gloria Swanson and Rudolph Valentino, was considered a lost film for several decades. Swanson lamented the loss of this and other films in her 1980 memoirs, but optimistically concluded: ‘I do not believe these films are gone forever.’ In 2000, a print was found in the Netherlands and restored by the Nederlands Filmmuseum and the Haghefilm Conservation. It turned up among about two thousand rusty film canisters donated by an eccentric Dutch collector, Joop van Liempd, of Haarlem. It was given its first modern screening in 2005, and has since been aired on Turner Classic Movies.

In the early 2000s, the German film Metropolis — which had been distributed in many different edits over the years — was restored to as close to the original version as possible, by reinstating edited footage and using computer technology to repair damaged footage. However, at that point, approximately a quarter of the original film footage was considered lost, according to the Kino Video DVD release of the restored film. On July 1, 2008, Berlin film experts announced that a copy of the film had been discovered in the archives of the film museum Museo del Cine in Buenos Aires, Argentina, which contained almost all of the scenes still missing from the 2002 restoration.[17][18] The film now has been restored very close to its premiere version. The restoration process is featured in the documentary Metropolis refundada.

In 2010, digital copies of ten early American films were presented to the Library of Congress by the Boris Yeltsin Presidential Library, the first film installment from the Russian state archives to be repatriated.[19]

Television material existing on film has sometimes been recovered. The 1951 pilot of I Love Lucy was long believed lost; but in 1990, the widow of one of the actors, Pepito Pérez (who played Pepito the Clown), found a copy. It has since been shown on television. Sometimes, a film believed lost in its original state has been restored, either through the process of colorization, or other restoration methods. "The Cage", the original 1964 pilot film for Star Trek, survived only in a black-and-white print until 1987, when a film archivist found an unmarked (mute) 35 mm reel in a Hollywood film laboratory with the negative trims of the unused scenes.[20]

Similarly, a number of videotaped television programmes, previously thought lost (see wiping) have been recovered as overseas Kinescope film prints from private collectors and various other sources over the years. For example, nine lost episodes of Doctor Who were discovered in storage at a television broadcasting station in Nigeria in 2013.[21]

Stock footage

Several films that would otherwise be entirely lost survive in the form of stock footage used for later films.

The Universal Pictures feature film The Cat Creeps (1930) is a lost film, and its only remaining footage was included in the Universal short film Boo! (1932). However, UCLA still has a copy of the soundtrack. The James Cagney film Winner Take All (1932) used scenes from the early talkie Queen of the Night Clubs (1929) starring Texas Guinan. While Queen of the Night Clubs was not a lost film in 1932, no prints of the film have survived through the decades, and the footage included in Winner Take All is all that remains.

Actress-turned-gossip columnist Hedda Hopper made her screen debut in the Fox Film The Battle of Hearts (1916). The star was William Farnum, then at the beginning of his long Fox contract. Twenty-six years later, in 1942, Hopper produced her short series Hedda Hopper's Hollywood #2. In the short, Hopper, Farnum, her son William Hopper, and William's wife Jane Gilbert viewed portions of The Battle of Hearts. These brief portions of that movie survive within the Hopper documentary. More than likely, Hopper had an entire print of the movie in 1942. However, like many early Fox films, The Battle of Hearts is now lost or missing.

One of the best-known Charlie Chaplin's works, silent film The Gold Rush (1925), was re-released in 1942 to include a musical track and narration by Chaplin himself. The reissue would end up having the unintentional result of preserving the film, as the original 1925 film (though generally not considered a lost film) shows noticeable degradation of image and missing frames, damage not evident in the 1942 version.

The Polish film O czym się nie mówi (1939) contains three short fragments of Arabella (1917), one of the early films of Pola Negri which later became lost.

In film

Several films have been made with lost film fragments incorporated into the work. Decasia (2002) used nothing but decaying film footage as an abstract tone poem of light and darkness, much like the more historical Lyrical Nitrate (Peter Delpeut, 1991) which contained only footage from canisters found stored in an Amsterdam cinema. In 1993, Delpeut released The Forbidden Quest, combining early film footage and archival photographs with new material to tell the fictional story of an ill-fated Antarctic expedition.

The 2016 documentary Dawson City: Frozen Time, about the history of Dawson City, Canada and the 1978 discovery of previously lost silent films there, incorporates parts of many of those films.

The mockumentary Forgotten Silver, made by Peter Jackson, purports to show recovered footage of early films. Instead, the filmmakers used newly shot film sequences treated to look like lost film.

In the double feature Grindhouse (2006), both segments - Planet Terror (directed by Robert Rodriguez) and Death Proof (directed by Quentin Tarantino) - have references to missing reels, used as plot devices.

"Cigarette Burns", an episode of the John Carpenter series Masters of Horror, deals with the search for a fictional lost film, La Fin Absolue Du Monde (The Absolute End of The World).

See also

References

- Pierce, David (September 2013). "The Survival of American Silent Feature Films: 1912–1929" (PDF). Library of Congress. Retrieved September 10, 2019.

- Report of the Register of Copyrights for the Fiscal Year 1912–1913, Library of Congress, 1913, p. 141.

- Dave Kehr (October 14, 2010). "Film Riches, Cleaned Up for Posterity". New York Times. Retrieved October 15, 2010.

It’s bad enough, to cite a common estimate, that 90 percent of all American silent films and 50 percent of American sound films made before 1950 appear to have vanished forever.

- Brian Dzyak (2010). What I Really Want to Do on Set in Hollywood: A Guide to Real Jobs in the Film Industry. Crown Publishing Group. pp. 303–. ISBN 978-0-307-87516-7.

- Robert Godwin, H.G. Wells The First Men in the Moon: the Story of the 1919 Film, Apogee Space Books, ISBN 978-1926837-31-4- see web page at Apogee books (retrieved May 5, 2014).

- "Silent Era : Presumed Lost". www.silentera.com.

- Film Preservation Archived March 12, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, The Film Foundation.

- Ohlheiser, Abby (December 4, 2013). "Most of America's Silent Films Are Lost Forever". The Wire. Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- Robert A. Harris, public hearing statement to the National Film Preservation Board of the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C., February 1993.

- Humphreys, Sally; Humphreys, Geraint (February 1, 2011). Century of Scandal. Haynes Publishing. ISBN 978-1-844259-50-2.

- "$45,000 Fire Drives Families From Homes in Little Ferry", Bergen Evening Record, July 9, 1937, p. 1. Quoted by Richard Koszarski in Fort Lee: The Film Town, Indiana University Press, 2005, pp. 339–341. ISBN 978-0-86196-652-3.

- Eileen Bowser, The Transformation of Cinema 1907–1915, Charles Scribner's Sons 1990, p. 74–75. ISBN 0-684-18414-1.

- "The Clara Bow Page".

- "Over 31,000 film reels 'lost or destroyed' at National Films Archives of India: CAG report". indianexpress.com. March 18, 2019.

- Paumgarten, Nick (October 18, 2004). "Weird Love". In the Vault. New Yorker.

- Mason, Anthony (September 24, 2013). "Lost Mary Pickford movie discovered in N.H. barn". CBS News. Retrieved June 24, 2014.

- Faraci, Devin (July 3, 2008). "METROPOLIS REBORN". CHUD. p. 1. Archived from the original on July 5, 2008.

- "Lost scenes of 'Metropolis' discovered in Argentina". The Local. July 2, 2008. Archived from the original on August 20, 2008.

- "'Lost' silent movies found in Russia, returned to U.S." cnn.com. October 21, 2010. Retrieved February 11, 2011.

- Bob Furmanek, post to Classic Horror Film Board, April 21, 2008. The reconstruction used the soundtrack of Roddenberry's 16mm print for those scenes otherwise without sound.

- "Doctor Who: Yeti classic among episodes found in Nigeria". bbc.com. October 11, 2013. Retrieved July 5, 2018.

External links

- Presumed Lost list at SilentEra

- International Lost Films Database

- Historic Fires at Universal Studios essay

- A Lost Film blog about lost films, outtakes, etc.

- How Do Silent Films Become “Lost”? essay at Silentology

- The Lost Movies list of 1970s titles at the Wayback Machine

- Film Threat's Top 50 Lost Films of All Time and Version 2.0

- American Silent Feature Film Database at the Library of Congress

- List of 7200 Lost U.S. Silent Feature Films 1912-29 at the Library of Congress

- Vitaphone Project finds and restores Vitaphone films and their soundtrack discs