Tennessee–Tombigbee Waterway

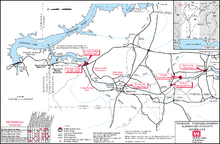

The Tennessee–Tombigbee Waterway (popularly known as the Tenn-Tom) is a 234-mile (377 km) man-made waterway that extends from the Tennessee River to the junction of the Black Warrior-Tombigbee River system near Demopolis, Alabama, United States. The Tennessee–Tombigbee Waterway links commercial navigation from the nation's midsection to the Gulf of Mexico. The major features of the waterway are ten locks and dams, a 175-foot-deep (53 m) cut between the Tombigbee River watershed and the Tennessee River watershed, and 234 miles (377 km) of navigation channels.[1] The ten locks are 9 by 110 by 600 feet (2.7 m × 33.5 m × 182.9 m), the same dimension as the locks on the Mississippi above Lock and Dam 26 at Alton, Illinois.[2][3] Under construction for twelve years by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the Tennessee–Tombigbee Waterway was completed in December 1984 at a total cost of nearly $2 billion.[4]

The Tenn-Tom encompasses 17 public ports and terminals, 110,000 acres (450 km2) of land, and another 88,000 acres (360 km2) managed by state conservation agencies for wildlife habitat preservation and recreational use.[4]

Early history and construction

First proposed in the Colonial period, the idea for a commercial waterway link between the Tennessee and Tombigbee rivers did not receive serious attention until the advent of steamboat traffic in the early nineteenth century. As steamboat efficiency gains caused water transport costs to decline, in 1875 engineers surveyed a potential canal route for the first time.[5] However, they issued a negative report, emphasizing that prohibitive cost estimates kept the project from economic feasibility.[5]

Enthusiasm for the project languished until the presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt. The development of the Tennessee River by the TVA, especially the construction of the Pickwick Lock and Dam in 1938, helped decrease the Tenn-Tom's potential economic costs and increase its potential benefits. Pickwick Lake's design included an embayment on its south shore at Yellow Creek, which would permit the design and construction of an entrance to a future southward waterway (leading to the Tombigbee River), should it be decided that such a waterway should be built in the future. Later, construction (under World War II emergency authorization) of Kentucky Dam at Gilbertsville, Kentucky, near the mouth of the Tennessee River's entrance into the Ohio River, would complete the "northern" half of the future waterway.[5] As early as 1941 the proposal was combined with other waterways, such as the St. Lawrence Seaway, with the aim of building broader political support.[6] Additionally, political candidates began to favor the construction of the waterway for political reasons, that is, in order to appeal to the voters in the South, rather than for economic reasons. In the early 1960s it was proposed that the canal could be created by use of atomic blasts.[7]

As part of his "Southern Strategy" for reelection, President Nixon included $1 million in the Corps of Engineers' 1971 budget to start construction of the Tenn-Tom.[8] Funding shortages and legal challenges delayed construction until December 1972, but President Nixon's efforts nevertheless initiated official Tenn-Tom waterway construction.[8]

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began work on the project in 1972. During the construction process, land excavation reached about 175 feet (53 m) in depth and required the excavation of nearly 310 million cubic yards of soil (the equivalent of more than 100 million dump truck loads). The project was completed on December 12, 1984, nearly two years ahead of schedule.[9]

Controversy

The $2 billion in required funding for the Tenn-Tom waterway was repeatedly attacked by elected representatives and political organizations. Opponents asserted that the estimated economic benefits of the waterway by the Corps of Engineers were unsupportable based on projected traffic volume. The waterway's essential economic rationales—that it would generate a demand for industries to locate along its banks, and use its barge handling capacity—simply did not (as its critics correctly predicted) materialize, nor did the growth in traffic volume on the existing Missouri – Ohio – Mississippi waterway require a second parallel route (the Tenn-Tom), between Cairo, Illinois, and the Gulf of Mexico. Immediately after his election, President Jimmy Carter announced a plan to slash Tenn-Tom federal funding.

By 1977, the Tenn-Tom was merely one of many such Corps of Engineers projects that had been initiated on the dubious rationale that they would somehow directly or indirectly return to the Treasury their cost(s) of construction. Carter, and the economic advisors recruited to his administration, objected not only to the "waste" of taxpayer dollars on pork-barrel projects; they strongly disapproved of the distortions in investment that such expenditures caused within the "real" economy.[8] However, after over 6,500 waterway supporters attended a public hearing held in Columbus, Mississippi, as part of Carter's review of the waterway, the President withdrew his opposition.[8]

A series of lawsuits were filed by the Louisville and Nashville Railroad to halt construction of the waterway.[10] Railroad companies, who served as a major transport alternative and stood to potentially lose the most value from its creation, asserted that the waterway construction violated the National Environmental Policy Act.[10] Nevertheless, federal courts ruled in favor of the project.[10]

An article published in the Tuscaloosa News on January 9, 2005, to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the opening of the canal noted that it carried just 7 million tons of cargo in 2004,[2] only one-quarter of the 28 million tons proponents of the canal had projected for the canal's first year. The Mississippi, in contrast, carried 307 million tons of cargo in 2004. Proponents had predicted the canal would carry 99 million tons by 2035.

Economic impact

When completed, the Tenn-Tom waterway's total cost was $1.992 billion, including non-federal costs, which led some political and economic commentators to deride the Tenn-Tom waterway as "pork-barrel politics at its worst".[5] For the first few years after its creation these criticisms appeared valid. The Tennessee–Tombigbee Waterway had opened in the midst of an economic recession in the barge business, which resulted in initially disappointingly low use of the waterway.[10]

The 1988 drought, however, closed the Mississippi River and shifted traffic to the Tenn-Tom canal.[8] This coincided with an economic turnaround on the Tennessee-Tombigbee corridor, wherein trade tonnage and commercial investment increased steadily over several years.

The two primary commodities shipped via the Tenn-Tom are coal and timber products, together comprising about 70 percent of total commercial shipping on the waterway.[11] The Tenn-Tom also provides access to over 34 million acres (140,000 km2) of commercial forests and approximately two-thirds of all recoverable coal reserves in the nation. Industries that utilize these natural resources have found the waterway to be their most cost-efficient mode of transportation.[11] Other popular Tenn-Tom trade products include grain, gravel, sand, and iron.

According to a 2009 Troy University study, since 1996 the United States has realized a direct, indirect, and induced economic impact of nearly $43 billion due to the existence and usage of the Tenn-Tom Waterway, and it has directly created more than 29,000 jobs.[11] Without the waterway as a viable source of transportation, an average of 284,000 additional truckloads per year would be required to handle the materials currently being shipped.[11]

Divide Cut

The Divide Cut (34°55′0″N 88°14′31″W) is a 29 mi (47 km) canal that makes the connection to the Tennessee River. It connects Pickwick Lake on the Tennessee to Bay Springs Lake, at Mississippi Highway 30. The cut carries the waterway between the Tennessee River watershed, which eventually empties into the Ohio River, and the Tombigbee River watershed, which eventually empties into the Gulf of Mexico at Mobile.

Pickwick Lake is a popular location for water sports such as waterskiing and wakeboarding.

For construction of the Divide Cut, the entire town of Holcut, Mississippi, had to be removed and demolished. Today, the Holcut Memorial lies alongside the waterway on the previous site of the town.

Locks and dams

The waterway is composed of ten locks (listed below from north to south along the waterway):

- Jamie Whitten Lock and Dam; formerly named Bay Springs Lock and Dam – impounds Bay Springs Lake 34°31′20″N 88°19′30″W

- G. V. Montgomery Lock; formerly named Lock E 34°27′47.06″N 88°21′53.5″W

- John Rankin Lock; formerly named Lock D 34°21′47.1″N 88°24′28.23″W

- Fulton Lock; located in Fulton, Mississippi, formerly named Lock C 34°15′28″N 88°25′29″W

- Glover Wilkins Lock; located in Smithville, Mississippi, formerly named Lock B 34°3′53.54″N 88°25′33.19″W

- Amory Lock; located in Amory, Mississippi, formerly named Lock A 34°00′40″N 88°29′21″W

- Aberdeen Lock and Dam; located in Aberdeen, Mississippi – impounds Aberdeen Lake 33°49′50″N 88°31′11″W

- John C. Stennis Lock and Dam; formerly named Columbus Lock and Dam – impounds Columbus Lake 33°31′5″N 88°29′20″W

- Tom Bevill Lock and Dam; formerly named Aliceville Lock and Dam – impounds Aliceville Lake 33°12′38″N 88°17′16″W

- Howell Heflin Lock and Dam; formerly named Gainesville Lock and Dam – impounds Gainesville Lake 32°50′12.86″N 88°8′8.73″W

Gallery

The Divide Cut under construction in the early 1980s

The Divide Cut under construction in the early 1980s Amory Lock at Amory, Mississippi

Amory Lock at Amory, Mississippi An Illinois Central Railroad (IC) bridge over the waterway at mile 424.8

An Illinois Central Railroad (IC) bridge over the waterway at mile 424.8 Detailed map of the Divide Cut (Corps of Engineers)

Detailed map of the Divide Cut (Corps of Engineers)

Notes

- "Tenn-Tom Waterway Key Components". 2009. Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway Development Authority. Available at <http://www.tenntom.org/about/ttwkeycomponents.htm>.

-

Johnny Kampis (January 9, 2005). "20-year anniversary of Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway: Canal's success debated". Tuscaloosa News. Archived from the original on August 19, 2016.

The Tenn-Tom is at least 300 feet wide over its entire length, but the inside dimensions of its 10 locks are 110 feet wide by 600 feet long ... The locks on the Mississippi River are the same dimensions as those on the Tenn-Tom, but none of them are south of St. Louis, which means commercial traffic isn't slowed down by navigating a lock system.

-

Lynn Seldon. "Boating the Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway". Retrieved January 2, 2013.

While early plans called for a canal 28 feet wide and four feet deep, with 44 locks, the 234-mile Waterway was built with a minimum width of 300 feet, a depth of nine feet (or more), and just 10 large locks (all 600 feet long and 110 feet wide).

- "About the Tenn-Tom Waterway". 2009. Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway Development Authority. Available at <http://www.tenntom.org/about/ttwhistory3.htm>.

- Van West, Carroll. Tennessee History. University of Tennessee Press, 1998.

- The St. Petersburg Times, April 13, 1941, pg 10

- The Florence (Alabama) Times, September 21, 1960, pg 3

- Ward, Rufus. Tombigbee River. History Press, 2010.

- Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway Development Authority.

- Ferris, William. Encyclopedia of Southern History. University of North Carolina, 1989.

- "Economic Impacts of the Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway". 2009. Troy University.

Further reading

- Patterson, Carolyn Bennett (March 1986). "The Tennessee–Tombigbee Waterway — Bounty or Boondoggle?". National Geographic. Vol. 169 no. 3. pp. 364–387. ISSN 0027-9358. OCLC 643483454.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |