Bodhidharma

Bodhidharma was a semi-legendary Buddhist monk who lived during the 5th or 6th century. He is traditionally credited as the transmitter of Chan Buddhism to China, and regarded as its first Chinese patriarch. According to Chinese legend, he also began the physical training of the monks of Shaolin Monastery that led to the creation of Shaolin kungfu. In Japan, he is known as Daruma. His name means "dharma of awakening (bodhi)" in Sanskrit.[1]

Bodhidharma

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Bodhidharma, Ukiyo-e woodblock print by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, 1887. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Title | Chanshi 1st Chan Patriarch | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Buddhism | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| School | Chan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Senior posting | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Huike | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Students

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Zen Buddhism |

|---|

|

|

Persons Chán in China Classical

Contemporary

Zen in Japan Seon in Korea Thiền in Vietnam Zen / Chán in the USA Category: Zen Buddhists |

|

Doctrines

|

|

Awakening |

|

Practice |

|

Schools

|

|

Related schools |

| Part of a series on |

| Chinese Buddhism 汉传佛教 / 漢傳佛教 |

|---|

Chinese: "Buddha" |

|

Major figures |

|

Architecture |

Little contemporary biographical information on Bodhidharma is extant, and subsequent accounts became layered with legend and unreliable details.[2][note 1]

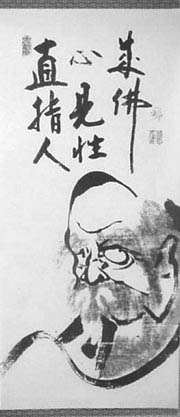

According to the principal Chinese sources, Bodhidharma came from the Western Regions,[5][6] which refers to Central Asia but may also include the Indian subcontinent, and was either a "Persian Central Asian"[5] or a "South Indian [...] the third son of a great Indian king."[6][note 2] Throughout Buddhist art, Bodhidharma is depicted as an ill-tempered, profusely-bearded, wide-eyed non-Chinese person. He is referred as "The Blue-Eyed Barbarian" (Chinese: 碧眼胡; pinyin: Bìyǎnhú) in Chan texts.[11]

Aside from the Chinese accounts, several popular traditions also exist regarding Bodhidharma's origins.[note 4]

The accounts also differ on the date of his arrival, with one early account claiming that he arrived during the Liu Song dynasty (420–479) and later accounts dating his arrival to the Liang dynasty (502–557). Bodhidharma was primarily active in the territory of the Northern Wei (386–534). Modern scholarship dates him to about the early 5th century.[16]

Bodhidharma's teachings and practice centered on meditation and the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra. The Anthology of the Patriarchal Hall (952) identifies Bodhidharma as the 28th Patriarch of Buddhism in an uninterrupted line that extends all the way back to the Gautama Buddha himself.[17] Bodhidharma also known as "The Wall-Gazing Brahmin".[18]

Biography

Principal sources

.png)

There are two known extant accounts written by contemporaries of Bodhidharma. According to these sources, Bodhidharma came from the Western Regions,[5][6] and was either a "Persian Central Asian"[5] or a "South Indian [...] the third son of a great Indian king."[6] Later sources draw on these two sources, adding additional details, including a change to being descendent from a Brahmin king,[8][9] which accords with the reign of the Pallavas, who "claim[ed] to belong to a brahmin lineage."[web 2][19]

The Western Regions was a historical name specified in the Chinese chronicles between the 3rd century BC to the 8th century AD[20] that referred to the regions west of Yumen Pass, most often Central Asia or sometimes more specifically the easternmost portion of it (e.g. Altishahr or the Tarim Basin in southern Xinjiang). Sometimes it was used more generally to refer to other regions to the west of China as well, such as the Indian subcontinent (as in the novel Journey to the West).

The Record of the Buddhist Monasteries of Luoyang

The earliest text mentioning Bodhidharma is The Record of the Buddhist Monasteries of Luoyang (Chinese: 洛陽伽藍記 Luòyáng Qiélánjì) which was compiled in 547 by Yang Xuanzhi (楊衒之), a writer and translator of Mahayana sutras into Chinese. Yang gave the following account:

At that time there was a monk of the Western Region named Bodhidharma, a Persian Central Asian.[note 5] He traveled from the wild borderlands to China. Seeing the golden disks on the pole on top of Yǒngníng's stupa reflecting in the sun, the rays of light illuminating the surface of the clouds, the jewel-bells on the stupa blowing in the wind, the echoes reverberating beyond the heavens, he sang its praises. He exclaimed: "Truly this is the work of spirits." He said: "I am 150 years old, and I have passed through numerous countries. There is virtually no country I have not visited. Even the distant Buddha-realms lack this." He chanted homage and placed his palms together in salutation for days on end.[5]

The account of Bodhidharma in the Luoyan Record does not particularly associate him with meditation, but rather depicts him as a thaumaturge capable of mystical feats. This may have played a role in his subsequent association with the martial arts and esoteric knowledge.[24]

Tanlin – preface to the Two Entrances and Four Acts

The second account was written by Tanlin (曇林; 506–574). Tanlin's brief biography of the "Dharma Master" is found in his preface to the Long Scroll of the Treatise on the Two Entrances and Four Practices, a text traditionally attributed to Bodhidharma and the first text to identify him as South Indian:

The Dharma Master was a South Indian of the Western Region. He was the third son of a great Indian king. His ambition lay in the Mahayana path, and so he put aside his white layman's robe for the black robe of a monk […] Lamenting the decline of the true teaching in the outlands, he subsequently crossed distant mountains and seas, traveling about propagating the teaching in Han and Wei.[6]

Tanlin's account was the first to mention that Bodhidharma attracted disciples,[25] specifically mentioning Daoyu (道育) and Dazu Huike (慧可), the latter of whom would later figure very prominently in the Bodhidharma literature. Although Tanlin has traditionally been considered a disciple of Bodhidharma, it is more likely that he was a student of Huike.[26]

"Chronicle of the Laṅkāvatāra Masters"

Tanlin's preface has also been preserved in Jingjue's (683–750) Lengjie Shizi ji "Chronicle of the Laṅkāvatāra Masters", which dates from 713–716.[4]/ca. 715[7] He writes,

The teacher of the Dharma, who came from South India in the Western Regions, the third son of a great Brahman king."[8]

"Further Biographies of Eminent Monks"

In the 7th-century historical work "Further Biographies of Eminent Monks" (續高僧傳 Xù gāosēng zhuàn), Daoxuan (道宣) possibly drew on Tanlin's preface as a basic source, but made several significant additions:

Firstly, Daoxuan adds more detail concerning Bodhidharma's origins, writing that he was of "South Indian Brahmin stock" (南天竺婆羅門種 nán tiānzhú póluómén zhŏng).[9]

Secondly, more detail is provided concerning Bodhidharma's journeys. Tanlin's original is imprecise about Bodhidharma's travels, saying only that he "crossed distant mountains and seas" before arriving in Wei. Daoxuan's account, however, implies "a specific itinerary":[27] "He first arrived at Nan-yüeh during the Sung period. From there he turned north and came to the Kingdom of Wei"[9] This implies that Bodhidharma had travelled to China by sea and that he had crossed over the Yangtze.

Thirdly, Daoxuan suggests a date for Bodhidharma's arrival in China. He writes that Bodhidharma makes landfall in the time of the Song, thus making his arrival no later than the time of the Song's fall to the Southern Qi in 479.[27]

Finally, Daoxuan provides information concerning Bodhidharma's death. Bodhidharma, he writes, died at the banks of the Luo River, where he was interred by his disciple Dazu Huike, possibly in a cave. According to Daoxuan's chronology, Bodhidharma's death must have occurred prior to 534, the date of the Northern Wei's fall, because Dazu Huike subsequently leaves Luoyang for Ye. Furthermore, citing the shore of the Luo River as the place of death might possibly suggest that Bodhidharma died in the mass executions at Heyin (河陰) in 528. Supporting this possibility is a report in the Chinese Buddhist canon stating that a Buddhist monk was among the victims at Héyīn.[28]

Later accounts

Anthology of the Patriarchal Hall

In the Anthology of the Patriarchal Hall (祖堂集 Zǔtángjí) of 952, the elements of the traditional Bodhidharma story are in place. Bodhidharma is said to have been a disciple of Prajñātāra,[29] thus establishing the latter as the 27th patriarch in India. After a three-year journey, Bodhidharma reached China in 527,[29] during the Liang (as opposed to the Song in Daoxuan's text). The Anthology of the Patriarchal Hall includes Bodhidharma's encounter with Emperor Wu of Liang, which was first recorded around 758 in the appendix to a text by Shenhui (神會), a disciple of Huineng.[30]

Finally, as opposed to Daoxuan's figure of "over 180 years,"[4] the Anthology of the Patriarchal Hall states that Bodhidharma died at the age of 150. He was then buried on Mount Xiong'er (熊耳山) to the west of Luoyang. However, three years after the burial, in the Pamir Mountains, Song Yun (宋雲)—an official of one of the later Wei kingdoms—encountered Bodhidharma, who claimed to be returning to India and was carrying a single sandal. Bodhidharma predicted the death of Song Yun's ruler, a prediction which was borne out upon the latter's return. Bodhidharma's tomb was then opened, and only a single sandal was found inside.

According to the Anthology of the Patriarchal Hall, Bodhidharma left the Liang court in 527 and relocated to Mount Song near Luoyang and the Shaolin Monastery, where he "faced a wall for nine years, not speaking for the entire time",[31] his date of death can have been no earlier than 536. Moreover, his encounter with the Wei official indicates a date of death no later than 554, three years before the fall of the Western Wei.

Record of the Masters and Students of the Laṅka

The Record of the Masters and Students of the Laṅka, which survives both in Chinese and in Tibetan translation (although the surviving Tibetan translation is apparently of older provenance than the surviving Chinese version), states that Bodhidharma is not the first ancestor of Zen, but instead the second. This text instead claims that Guṇabhadra, the translator of the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra, is the first ancestor in the lineage. It further states that Bodhidharma was his student. The Tibetan translation is estimated to have been made in the late eighth or early ninth century, indicating that the original Chinese text was written at some point before that.[32]

Daoyuan – Transmission of the Lamp

Subsequent to the Anthology of the Patriarchal Hall, the only dated addition to the biography of Bodhidharma is in the Jingde Records of the Transmission of the Lamp (景德傳燈錄 Jĭngdé chuándēng lù, published 1004 CE), by Daoyuan (道原), in which it is stated that Bodhidharma's original name had been Bodhitāra but was changed by his master Prajñātāra.[33] The same account is given by the Japanese master Keizan's 13th-century work of the same title.[34]

Popular traditions

Several contemporary popular traditions also exist regarding Bodhidharma's origins. An Indian tradition regards Bodhidharma to be the third son of a Pallava king from Kanchipuram.[12][note 3] This is consistent with the Southeast Asian traditions which also describe Bodhidharma as a former South Indian Tamil prince who had awakened his kundalini and renounced royal life to become a monk.[14] The Tibetan version similarly characterises him as a dark-skinned siddha from South India.[15] Conversely, the Japanese tradition generally regards Bodhidharma as Persian.[web 1]

Legends about Bodhidharma

Several stories about Bodhidharma have become popular legends, which are still being used in the Ch'an, Seon and Zen-tradition.

Encounter with Emperor Wu of Liang

The Anthology of the Patriarchal Hall says that in 527, Bodhidharma visited Emperor Wu of Liang, a fervent patron of Buddhism:

Emperor Wu: "How much karmic merit have I earned for ordaining Buddhist monks, building monasteries, having sutras copied, and commissioning Buddha images?"

Bodhidharma: "None. Good deeds done with worldly intent bring good karma, but no merit."

Emperor Wu: "So what is the highest meaning of noble truth?"

Bodhidharma: "There is no noble truth, there is only emptiness."

Emperor Wu: "Then, who is standing before me?"

Bodhidharma: "I know not, Your Majesty."[35]

This encounter was included as the first kōan of the Blue Cliff Record.

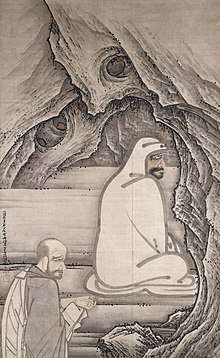

Nine years of wall-gazing

Failing to make a favorable impression in South China, Bodhidharma is said to have travelled to the Shaolin Monastery. After either being refused entry or being ejected after a short time, he lived in a nearby cave, where he "faced a wall for nine years, not speaking for the entire time".[31]

The biographical tradition is littered with apocryphal tales about Bodhidharma's life and circumstances. In one version of the story, he is said to have fallen asleep seven years into his nine years of wall-gazing. Becoming angry with himself, he cut off his eyelids to prevent it from happening again.[36] According to the legend, as his eyelids hit the floor the first tea plants sprang up, and thereafter tea would provide a stimulant to help keep students of Chan awake during zazen.[37]

The most popular account relates that Bodhidharma was admitted into the Shaolin temple after nine years in the cave and taught there for some time. However, other versions report that he "passed away, seated upright";[31] or that he disappeared, leaving behind the Yijin Jing;[38] or that his legs atrophied after nine years of sitting,[39] which is why Daruma dolls have no legs.

Huike cuts off his arm

In one legend, Bodhidharma refused to resume teaching until his would-be student, Dazu Huike, who had kept vigil for weeks in the deep snow outside of the monastery, cut off his own left arm to demonstrate sincerity.[36][note 6]

Transmission

Skin, flesh, bone, marrow

Jingde Records of the Transmission of the Lamp (景德传灯录) of Daoyuan, presented to the emperor in 1004, records that Bodhidharma wished to return to India and called together his disciples:

Bodhidharma asked, "Can each of you say something to demonstrate your understanding?"

Dao Fu stepped forward and said, "It is not bound by words and phrases, nor is it separate from words and phrases. This is the function of the Tao."

Bodhidharma: "You have attained my skin."

The nun Zong Chi[note 7][note 8] stepped up and said, "It is like a glorious glimpse of the realm of Akshobhya Buddha. Seen once, it need not be seen again."

Bodhidharma; "You have attained my flesh."

Dao Yu said, "The four elements are all empty. The five skandhas are without actual existence. Not a single dharma can be grasped."

Bodhidharma: "You have attained my bones."

Finally, Huike came forth, bowed deeply in silence and stood up straight.

Bodhidharma said, "You have attained my marrow." [42]

Bodhidharma passed on the symbolic robe and bowl of dharma succession to Dazu Huike and, some texts claim, a copy of the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra.[43] Bodhidharma then either returned to India or died.

Bodhidharma at Shaolin

Some Chinese myths and legends describe Bodhidharma as being disturbed by the poor physical shape of the Shaolin monks,[44] after which he instructed them in techniques to maintain their physical condition as well as teaching meditation.[44] He is said to have taught a series of external exercises called the Eighteen Arhat Hands[44] and an internal practice called the Sinew Metamorphosis Classic.[45] In addition, after his departure from the temple, two manuscripts by Bodhidharma were said to be discovered inside the temple: the Yijin Jing and the Xisui Jing. Copies and translations of the Yijin Jing survive to the modern day. The Xisui Jing has been lost.[46]

Travels in Southeast Asia

According to Southeast Asian folklore, Bodhidharma travelled from Jambudvipa by sea to Palembang, Indonesia. Passing through Sumatra, Java, Bali, and Malaysia, he eventually entered China through Nanyue. In his travels through the region, Bodhidharma is said to have transmitted his knowledge of the Mahayana doctrine and the martial arts. Malay legend holds that he introduced forms to silat.[47]

Vajrayana tradition links Bodhidharma with the 11th-century south Indian monk Dampa Sangye who travelled extensively to Tibet and China spreading tantric teachings.[48]

Appearance after his death

Three years after Bodhidharma's death, Ambassador Song Yun of northern Wei is said to have seen him walking while holding a shoe at the Pamir Mountains. Song asked Bodhidharma where he was going, to which Bodhidharma replied "I am going home". When asked why he was holding his shoe, Bodhidharma answered "You will know when you reach Shaolin monastery. Don't mention that you saw me or you will meet with disaster". After arriving at the palace, Song told the emperor that he met Bodhidharma on the way. The emperor said Bodhidharma was already dead and buried and had Song arrested for lying. At Shaolin Monastery, the monks informed them that Bodhidharma was dead and had been buried in a hill behind the temple. The grave was exhumed and was found to contain a single shoe. The monks then said "Master has gone back home" and prostrated three times: "For nine years he had remained and nobody knew him; Carrying a shoe in hand he went home quietly, without ceremony."[49]

Practice and teaching

Bodhidharma is traditionally seen as introducing dhyana-practice in China.

Pointing directly to one's mind

One of the fundamental Chán texts attributed to Bodhidharma is a four-line stanza whose first two verses echo the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra's disdain for words and whose second two verses stress the importance of the insight into reality achieved through "self-realization":

A special transmission outside the scriptures

Not founded upon words and letters;

By pointing directly to [one's] mind

It lets one see into [one's own true] nature and [thus] attain Buddhahood.[50]

The stanza, in fact, is not Bodhidharma's, but rather dates to the year 1108.[51]

Wall-gazing

Tanlin, in the preface to Two Entrances and Four Acts, and Daoxuan, in the Further Biographies of Eminent Monks, mention a practice of Bodhidharma's termed "wall-gazing" (壁觀 bìguān). Both Tanlin[note 9] and Daoxuan[web 5] associate this "wall-gazing" with "quieting [the] mind"[25] (Chinese: 安心; pinyin: ānxīn).

In the Two Entrances and Four Acts, traditionally attributed to Bodhidharma, the term "wall-gazing" is given as follows:

Those who turn from delusion back to reality, who meditate on walls, the absence of self and other, the oneness of mortal and sage, and who remain unmoved even by scriptures are in complete and unspoken agreement with reason".[53][note 10]

Daoxuan states, "The merits of Mahāyāna wall-gazing are the highest".[54]

These are the first mentions in the historical record of what may be a type of meditation being ascribed to Bodhidharma.

Exactly what sort of practice Bodhidharma's "wall-gazing" was remains uncertain. Nearly all accounts have treated it either as an undefined variety of meditation, as Daoxuan and Dumoulin,[54] or as a variety of seated meditation akin to the zazen (Chinese: 坐禪; pinyin: zuòchán) that later became a defining characteristic of Chan. The latter interpretation is particularly common among those working from a Chan standpoint.[web 6][web 7]

There have also, however, been interpretations of "wall-gazing" as a non-meditative phenomenon.[note 11]

The Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra

There are early texts which explicitly associate Bodhidharma with the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra. Daoxuan, for example, in a late recension of his biography of Bodhidharma's successor Huike, has the sūtra as a basic and important element of the teachings passed down by Bodhidharma:

In the beginning Dhyana Master Bodhidharma took the four-roll Laṅkā Sūtra, handed it over to Huike, and said: "When I examine the land of China, it is clear that there is only this sutra. If you rely on it to practice, you will be able to cross over the world."[40]

Another early text, the "Record of the Masters and Disciples of the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra" (Chinese: 楞伽師資記; pinyin: Léngqié Shīzī Jì) of Jingjue (淨覺; 683–750), also mentions Bodhidharma in relation to this text. Jingjue's account also makes explicit mention of "sitting meditation" or zazen:[web 8]

For all those who sat in meditation, Master Bodhi[dharma] also offered expositions of the main portions of the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra, which are collected in a volume of twelve or thirteen pages […] bearing the title of "Teaching of [Bodhi-]Dharma".[8]

In other early texts, the school that would later become known as Chan Buddhism is sometimes referred to as the "Laṅkāvatāra school" (楞伽宗 Léngqié zōng).[56]

The Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra, one of the Mahayana sutras, is a highly "difficult and obscure" text[57] whose basic thrust is to emphasize "the inner enlightenment that does away with all duality and is raised above all distinctions".[58] It is among the first and most important texts for East Asian Yogācāra.[59]

One of the recurrent emphases in the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra is a lack of reliance on words to effectively express reality:

If, Mahamati, you say that because of the reality of words the objects are, this talk lacks in sense. Words are not known in all the Buddha-lands; words, Mahamati, are an artificial creation. In some Buddha-lands ideas are indicated by looking steadily, in others by gestures, in still others by a frown, by the movement of the eyes, by laughing, by yawning, or by the clearing of the throat, or by recollection, or by trembling.[60]

In contrast to the ineffectiveness of words, the sūtra instead stresses the importance of the "self-realization" that is "attained by noble wisdom"[61] and occurs "when one has an insight into reality as it is":[62] "The truth is the state of self-realization and is beyond categories of discrimination".[63] The sūtra goes on to outline the ultimate effects of an experience of self-realization:

[The bodhisattva] will become thoroughly conversant with the noble truth of self-realization, will become a perfect master of his own mind, will conduct himself without effort, will be like a gem reflecting a variety of colours, will be able to assume the body of transformation, will be able to enter into the subtle minds of all beings, and, because of his firm belief in the truth of Mind-only, will, by gradually ascending the stages, become established in Buddhahood.[64]

Lineage

Construction of lineages

The idea of a patriarchal lineage in Ch'an dates back to the epitaph for Faru (法如), a disciple of the 5th patriarch Hongren (弘忍). In the Long Scroll of the Treatise on the Two Entrances and Four Practices and the Continued Biographies of Eminent Monks, Daoyu and Dazu Huike are the only explicitly identified disciples of Bodhidharma. The epitaph gives a line of descent identifying Bodhidharma as the first patriarch.[65][66]

In the 6th century biographies of famous monks were collected. From this genre the typical Chan lineage was developed:

These famous biographies were non-sectarian. The Ch'an biographical works, however, aimed to establish Ch'an as a legitimate school of Buddhism traceable to its Indian origins, and at the same time championed a particular form of Ch'an. Historical accuracy was of little concern to the compilers; old legends were repeated, new stories were invented and reiterated until they too became legends.[67]

D. T. Suzuki contends that Chan's growth in popularity during the 7th and 8th centuries attracted criticism that it had "no authorized records of its direct transmission from the founder of Buddhism" and that Chan historians made Bodhidharma the 28th patriarch of Buddhism in response to such attacks.[68]

Six patriarchs

The earliest lineages described the lineage from Bodhidharma into the 5th to 7th generation of patriarchs. Various records of different authors are known, which give a variation of transmission lines:

| The Continued Biographies of Eminent Monks Xù gāosēng zhuàn 續高僧傳 Daoxuan 道宣 (596–667) |

The Record of the Transmission of the Dharma-Jewel Chuán fǎbǎo jì 傳法寶記 Dù Fěi 杜胐 |

History of Masters and Disciples of the Laṅkāvatāra-Sūtra Léngqié shīzī jì 楞伽師資紀記 Jìngjué 淨覺 (ca. 683 – ca. 650) |

Xiǎnzōngjì 显宗记 of Shénhuì 神会 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bodhidharma | Bodhidharma | Bodhidharma | Bodhidharma |

| 2 | Huìkě 慧可 (487? – 593) | Dàoyù 道育 | Dàoyù 道育 | Dàoyù 道育 |

| Huìkě 慧可 (487? – 593) | Huìkě 慧可 (487? – 593) | Huìkě 慧可 (487? – 593) | ||

| 3 | Sēngcàn 僧璨 (d.606) | Sēngcàn 僧璨 (d.606) | Sēngcàn 僧璨 (d.606) | Sēngcàn 僧璨 (d.606) |

| 4 | Dàoxìn 道信 (580–651) | Dàoxìn 道信 (580–651) | Dàoxìn 道信 (580–651) | Dàoxìn 道信 (580–651) |

| 5 | Hóngrěn 弘忍 (601–674) | Hóngrěn 弘忍 (601–674) | Hóngrěn 弘忍 (601–674) | Hóngrěn 弘忍 (601–674) |

| 6 | - | Fǎrú 法如 (638–689) | Shénxiù 神秀 (606? – 706) | Huìnéng 慧能 (638–713) |

| Shénxiù 神秀 (606? – 706) 神秀 (606? – 706) | Xuánzé 玄賾 | |||

| 7 | – | – | – | Xuánjué 玄覺 (665–713) |

Continuous lineage from Gautama Buddha

Eventually these descriptions of the lineage evolved into a continuous lineage from Śākyamuni Buddha to Bodhidharma. The idea of a line of descent from Śākyamuni Buddha is the basis for the distinctive lineage tradition of Chan Buddhism.

According to the Song of Enlightenment (證道歌 Zhèngdào gē) by Yongjia Xuanjue,[69] one of the chief disciples of Huìnéng, was Bodhidharma, the 28th Patriarch of Buddhism in a line of descent from Gautama Buddha via his disciple Mahākāśyapa:

Mahakashyapa was the first, leading the line of transmission;

Twenty-eight Fathers followed him in the West;

The Lamp was then brought over the sea to this country;

And Bodhidharma became the First Father here

His mantle, as we all know, passed over six Fathers,

And by them many minds came to see the Light.[70]

The Transmission of the Light gives 28 patriarchs in this transmission:[34][71]

| Sanskrit | Chinese | Vietnamese | Japanese | Korean | |

| 1 | Mahākāśyapa | 摩訶迦葉 / Móhējiāyè | Ma-Ha-Ca-Diếp | Makakashō | 마하가섭 / Mahagasŏp |

| 2 | Ānanda | 阿難陀 (阿難) / Ānántuó (Ānán) | A-Nan-Đà (A-Nan) | Ananda (Anan) | 아난다 (아난) / Ananda (Anan) |

| 3 | Śānavāsa | 商那和修 / Shāngnàhéxiū | Thương-Na-Hòa-Tu | Shōnawashu | 상나화수 / Sangnahwasu |

| 4 | Upagupta | 優婆掬多 / Yōupójúduō | Ưu-Ba-Cúc-Đa | Ubakikuta | 우바국다 / Upakukta |

| 5 | Dhrtaka | 提多迦 / Dīduōjiā | Đề-Đa-Ca | Daitaka | 제다가 / Chedaga |

| 6 | Miccaka | 彌遮迦 / Mízhējiā | Di-Dá-Ca | Mishaka | 미차가 / Michaga |

| 7 | Vasumitra | 婆須密 (婆須密多) / Póxūmì (Póxūmìduō) | Bà-Tu-Mật (Bà-Tu-Mật-Đa) | Bashumitsu (Bashumitta) | 바수밀다 / Pasumilta |

| 8 | Buddhanandi | 浮陀難提 / Fútuónándī | Phật-Đà-Nan-Đề | Buddanandai | 불타난제 / Pŭltananje |

| 9 | Buddhamitra | 浮陀密多 / Fútuómìduō | Phục-Đà-Mật-Đa | Buddamitta | 복태밀다 / Puktaemilda |

| 10 | Pārśva | 波栗濕縛 / 婆栗濕婆 (脅尊者) / Bōlìshīfú / Pólìshīpó (Xiézūnzhě) | Ba-Lật-Thấp-Phược / Bà-Lật-Thấp-Bà (Hiếp-Tôn-Giả) | Barishiba (Kyōsonja) | 파률습박 (협존자) / P'ayulsŭppak (Hyŏpjonje) |

| 11 | Punyayaśas | 富那夜奢 / Fùnàyèshē | Phú-Na-Dạ-Xa | Funayasha | 부나야사 / Punayasa |

| 12 | Ānabodhi / Aśvaghoṣa | 阿那菩提 (馬鳴) / Ānàpútí (Mǎmíng) | A-Na-Bồ-Đề (Mã-Minh) | Anabotei (Memyō) | 아슈바고샤 (마명) / Asyupakosya (Mamyŏng) |

| 13 | Kapimala | 迦毘摩羅 / Jiāpímóluó | Ca-Tỳ-Ma-La | Kabimora (Kabimara) | 가비마라 / Kabimara |

| 14 | Nāgārjuna | 那伽閼剌樹那 (龍樹) / Nàqiéèlàshùnà (Lóngshù) | Na-Già-Át-Lạt-Thụ-Na (Long-Thọ) | Nagaarajuna (Ryūju) | 나가알랄수나 (용수) / Nakaallalsuna (Yongsu) |

| 15 | Āryadeva / Kānadeva | 迦那提婆 / Jiānàtípó | Ca-Na-Đề-Bà | Kanadaiba | 가나제바 / Kanajeba |

| 16 | Rāhulata | 羅睺羅多 / Luóhóuluóduō | La-Hầu-La-Đa | Ragorata | 라후라다 / Rahurada |

| 17 | Sanghānandi | 僧伽難提 / Sēngqiénántí | Tăng-Già-Nan-Đề | Sōgyanandai | 승가난제 / Sŭngsananje |

| 18 | Sanghayaśas | 僧伽舍多 / Sēngqiéshèduō | Tăng-Già-Da-Xá | Sōgyayasha | 가야사다 / Kayasada |

| 19 | Kumārata | 鳩摩羅多 / Jiūmóluóduō | Cưu-Ma-La-Đa | Kumorata (Kumarata) | 구마라다 / Kumarada |

| 20 | Śayata / Jayata | 闍夜多 / Shéyèduō | Xà-Dạ-Đa | Shayata | 사야다 / Sayada |

| 21 | Vasubandhu | 婆修盤頭 (世親) / Póxiūpántóu (Shìqīn) | Bà-Tu-Bàn-Đầu (Thế-Thân) | Bashubanzu (Sejin) | 바수반두 (세친) / Pasubandu (Sechin) |

| 22 | Manorhita | 摩拏羅 / Mónáluó | Ma-Noa-La | Manura | 마나라 / Manara |

| 23 | Haklenayaśas | 鶴勒那 (鶴勒那夜奢) / Hèlènà (Hèlènàyèzhě) | Hạc-Lặc-Na | Kakurokuna (Kakurokunayasha) | 학륵나 / Haklŭkna |

| 24 | Simhabodhi | 師子菩提 / Shīzǐpútí | Sư-Tử-Bồ-Đề / Sư-Tử-Trí | Shishibodai | 사자 / Saja |

| 25 | Vasiasita | 婆舍斯多 / Póshèsīduō | Bà-Xá-Tư-Đa | Bashashita | 바사사다 / Pasasada |

| 26 | Punyamitra | 不如密多 / Bùrúmìduō | Bất-Như-Mật-Đa | Funyomitta | 불여밀다 / Punyŏmilta |

| 27 | Prajñātāra | 般若多羅 / Bānruòduōluó | Bát-Nhã-Đa-La | Hannyatara | 반야다라 / Panyadara |

| 28 | Dharma / Bodhidharma | Ta Mo / 菩提達磨 / Pútídámó | Đạt-Ma / Bồ-Đề-Đạt-Ma | Daruma / Bodaidaruma | Tal Ma / 보리달마 / Poridalma |

Modern scholarship

Bodhidharma has been the subject of critical scientific research, which has shed new light on the traditional stories about Bodhidharma.

Biography as a hagiographic process

According to John McRae, Bodhidharma has been the subject of a hagiographic process which served the needs of Chan Buddhism. According to him it is not possible to write an accurate biography of Bodhidharma:

It is ultimately impossible to reconstruct any original or accurate biography of the man whose life serves as the original trace of his hagiography – where "trace" is a term from Jacques Derrida meaning the beginningless beginning of a phenomenon, the imagined but always intellectually unattainable origin. Hence any such attempt by modern biographers to reconstruct a definitive account of Bodhidharma's life is both doomed to failure and potentially no different in intent from the hagiographical efforts of premodern writers.[72]

McRae's standpoint accords with Yanagida's standpoint: "Yanagida ascribes great historical value to the witness of the disciple Tanlin, but at the same time acknowledges the presence of "many puzzles in the biography of Bodhidharma". Given the present state of the sources, he considers it impossible to compile a reliable account of Bodhidharma's life.[8]

Several scholars have suggested that the composed image of Bodhidharma depended on the combination of supposed historical information on various historical figures over several centuries.[73] Bodhidharma as a historical person may even never have actually existed.[74]

Origins and place of birth

Dumoulin comments on the three principal sources. The Persian heritage is doubtful, according to Dumoulin: "In the Description of the Lo-yang temple, bodhidharma is called a Persian. Given the ambiguity of geographical references in writings of this period, such a statement should not be taken too seriously."[75] Dumoulin considers Tanlin's account of Bodhidharma being "the third son of a great Brahman king" to be a later addition, and finds the exact meaning of "South Indian Brahman stock" unclear: "And when Daoxuan speaks of origins from South Indian Brahman stock, it is not clear whether he is referring to roots in nobility or to India in general as the land of the Brahmans."[76]

These Chinese sources lend themselves to make inferences about Bodhidharma's origins. "The third son of a Brahman king" has been speculated to mean "the third son of a Pallavine king".[12] Based on a specific pronunciation of the Chinese characters 香至 as Kang-zhi, "meaning fragrance extreme",[12] Tsutomu Kambe identifies 香至 to be Kanchipuram, an old capital town in the state Tamil Nadu, India. According to Tsutomu Kambe, "Kanchi means 'a radiant jewel' or 'a luxury belt with jewels', and puram means a town or a state in the sense of earlier times. Thus, it is understood that the '香至-Kingdom' corresponds to the old capital 'Kanchipuram'."[12]

Acharya Raghu, in his work 'Bodhidharma Retold', used a combination of multiple factors to identify Bodhidharma from the state of Andhra Pradesh in South India, specifically to the geography around Mt. Sailum or modern day Srisailam. [77]

The Pakistani scholar Ahmad Hasan Dani speculated that according to popular accounts in Pakistan's northwest, Bodhidharma may be from the region around the Peshawar valley, or possibly around modern Afghanistan's eastern border with Pakistan.[78]

Caste

In the context of the Indian caste system the mention of "Brahman king"[8] acquires a nuance. Broughton notes that "king" implies that Bodhidharma was of caste of warriors and rulers.[29] Brahman is, in western contexts, easily understood as Brahmana or Brahmin, which means priest.

Name

According to tradition Bodhidharma was given this name by his teacher known variously as Panyatara, Prajnatara, or Prajñādhara.[79] His name prior to monkhood is said to be Jayavarman.[14]

Bodhidharma is associated with several other names, and is also known by the name Bodhitara. Faure notes that:

Bodhidharma’s name appears sometimes truncated as Bodhi, or more often as Dharma (Ta-mo). In the first case, it may be confused with another of his rivals, Bodhiruci.[80]

Tibetan sources give his name as "Bodhidharmottara" or "Dharmottara", that is, "Highest teaching (dharma) of enlightenment".[1]

Abode in China

Buswell dates Bodhidharma abode in China approximately at the early 5th century.[81] Broughton dates Bodhidharma's presence in Luoyang to between 516 and 526, when the temple referred to—Yongning Temple (永寧寺), was at the height of its glory.[82] Starting in 526, Yǒngníngsì suffered damage from a series of events, ultimately leading to its destruction in 534.[83]

Shaolin boxing

Traditionally Bodhidharma is credited as founder of the martial arts at the Shaolin Temple. However, martial arts historians have shown this legend stems from a 17th-century qigong manual known as the Yijin Jing.[84] The preface of this work says that Bodhidharma left behind the Yi Jin Jing, from which the monks obtained the fighting skills which made them gain some fame.[38]

The authenticity of the Yijin Jing has been discredited by some historians including Tang Hao, Xu Zhen and Matsuda Ryuchi. According to Lin Boyuan, "This manuscript is full of errors, absurdities and fantastic claims; it cannot be taken as a legitimate source."[38][note 12]

The oldest available copy was published in 1827.[85] The composition of the text itself has been dated to 1624.[38] Even then, the association of Bodhidharma with martial arts only became widespread as a result of the 1904–1907 serialization of the novel The Travels of Lao Ts'an in Illustrated Fiction Magazine.[86] According to Henning, the "story is clearly a twentieth-century invention," which "is confirmed by writings going back at least 250 years earlier, which mention both Bodhidharma and martial arts but make no connection between the two."[87][note 13]

Works attributed to Bodhidharma

- Two Entrances and Four Practices,《二入四行論》

- The Bloodstream sermon《血脈論》

- Dharma Teaching of Pacifying the Mind《安心法門》

- Treatise on Realizing the Nature《悟性論》

- Bodhidharma Treatise《達摩論》

- Refuting Signs Treatise 《破相論》(a.k.a. Contemplation of Mind Treatise《觀心論》)

- Two Types of Entrance《二種入》

See also

Notes

- There are three principal sources for Bodhidharma's biography:[3]

- Yang Xuanzhi's The Record of the Buddhist Monasteries of Luoyang (547);

- Tanlin's preface to the Two Entrances and Four Acts (6th century CE), which is also preserved in Ching-chüeh's Chronicle of the Lankavatar Masters (713–716);[4]

- Daoxuan's Further Biographies of Eminent Monks (7th century CE).

- The origins which are mentioned in these sources are:

- "[A] monk of the Western Region named Bodhidharma, a Persian Central Asian"[5] c.q. "from Persia"[7] (Buddhist monasteries, 547);

- "[A] South Indian of the Western Region. He was the third son of a great Indian king."[6] (Tanlin, 6th century CE);

- "[W]ho came from South India in the Western Regions, the third son of a great Brahman king"[8] c.q. "the third son of a Brahman of South India" [7] (Lankavatara Masters, 713–716[4]/ca. 715[7]);

- "[O]f South Indian Brahman stock"[9] c.q. "a Brahman monk from South India"[7] (Further Biographies, 645).

- See also South India, Dravidian peoples, Tamil people and Tamil nationalism for backgrounds on the Tamil identity.

- An Indian tradition regards Bodhidharma to be the third son of a Tamil Pallava king from Kanchipuram.[12][13][note 3] The Tibetan and Southeast traditions consistently regard Bodhidharma as South Indian,[14] the former in particular characterising him as a dark-skinned Dravidian.[15] Conversely, the Japanese tradition generally regards Bodhidharma as Persian.[web 1]

- Bodhidharma's first language was likely one of the many Eastern Iranian languages (such as Sogdian or Bactrian), that were commonly spoken in most of Central Asia during his lifetime and, in using the more specific term "Persian", Xuànzhī likely erred. As Jorgensen has pointed out, the Sassanian realm contemporary to Bodhidharma was not Buddhist. Johnston supposes that Yáng Xuànzhī mistook the name of the south-Indian Pallava dynasty for the name of the Sassanian Pahlavi dynasty;[19] however, Persian Buddhists did exist within the Sassanian realm, particularly in the formerly Greco-Buddhist east, see Persian Buddhism.

- Daoxuan records that Huìkě's arm was cut off by bandits.[40]

- Various names are given for this nun. Zōngzhǐ is also known by her title Soji, and by Myoren, her nun name. In the Jǐngdé Records of the Transmission of the Lamp, Dharani repeats the words said by the nun Yuanji in the Two Entrances and Four Acts, possibly identifying the two with each other .[41] Heng-Ching Shih states that according to the Jǐngdé chuándēng lù 景德传灯录 the first `bhikṣuni` mentioned in the Chán literature was a disciple of the First Chan Patriarch, Bodhidharma, known as Zōngzhǐ 宗旨 [early-mid 6th century][web 3]

- In the Shōbōgenzō 正法眼蔵 chapter called Katto ("Twining Vines") by Dōgen Zenji (道元禅師), she is named as one of Bodhidharma's four Dharma heirs. Although the First Patriarch's line continued through another of the four, Dogen emphasizes that each of them had a complete understanding of the teaching.[web 4]

- [52] translates 壁觀 as "wall-examining".

- [25] offers a more literal rendering of the key phrase 凝住壁觀 (níngzhù bìguān) as "[who] in a coagulated state abides in wall-examining".

- viz., [55] where a Tibetan Buddhist interpretation of "wall-gazing" as being akin to Dzogchen is offered.

- This argument is summarized by modern historian Lin Boyuan in his Zhongguo wushu shi: "As for the "Yi Jin Jing" (Muscle Change Classic), a spurious text attributed to Bodhidharma and included in the legend of his transmitting martial arts at the temple, it was written in the Ming dynasty, in 1624, by the Daoist priest Zining of Mt. Tiantai, and falsely attributed to Bodhidharma. Forged prefaces, attributed to the Tang general Li Jing and the Southern Song general Niu Gao were written. They say that, after Bodhidharma faced the wall for nine years at Shaolin temple, he left behind an iron chest; when the monks opened this chest they found the two books "Xi Sui Jing" (Marrow Washing Classic) and "Yi Jin Jing" within. The first book was taken by his disciple Huike, and disappeared; as for the second, "the monks selfishly coveted it, practicing the skills therein, falling into heterodox ways, and losing the correct purpose of cultivating the Real. The Shaolin monks have made some fame for themselves through their fighting skill; this is all due to having obtained this manuscript." Based on this, Bodhidharma was claimed to be the ancestor of Shaolin martial arts. This manuscript is full of errors, absurdities and fantastic claims; it cannot be taken as a legitimate source."[38]

- Henning: "One of the most recently invented and familiar of the Shaolin historical narratives is a story that claims that the Indian monk Bodhidharma, the supposed founder of Chinese Chan (Zen) Buddhism, introduced boxing into the monastery as a form of exercise around a.d. 525. This story first appeared in a popular novel, The Travels of Lao T’san, published as a series in a literary magazine in 1907. This story was quickly picked up by others and spread rapidly through publication in a popular contemporary boxing manual, Secrets of Shaolin Boxing Methods, and the first Chinese physical culture history published in 1919. As a result, it has enjoyed vast oral circulation and is one of the most "sacred" of the narratives shared within Chinese and Chinese-derived martial arts. That this story is clearly a twentieth-century invention is confirmed by writings going back at least 250 years earlier, which mention both Bodhidharma and martial arts but make no connection between the two.[87]

References

- Goodman & Davidson 1992, p. 65.

- McRae 2003, p. 26-27.

- Dumoulin, Heisig & Knitter 2005, p. 85-90.

- Dumoulin, Heisig & Knitter 2005, p. 88.

- Broughton 1999, p. 54–55.

- Broughton 1999, p. 8.

- McRae 2003, p. 26.

- Dumoulin, Heisig & Knitter 2005, p. 89.

- Dumoulin, Heisig & Knitter 2005, p. 87.

- Broughton 1999, p. 54-55.

- Soothill & Hodous 1995.

- Kambe 2012.

- Zvelebil 1987, p. 125-126.

- Anand Krishna (2005). Bodhidharma: Kata Awal adalah Kata Akhir (in Indonesian). Gramedia Pustaka Utama. ISBN 9792217711.

- Edou 1996.

- Macmillan (publisher) 2003, p. 57, 130.

- Philippe Cornu, Dictionnaire enclyclopédique du Bouddhisme

- Nukariya, Kaiten (2012). The Religion Of The Samurai. Jazzybee Verlag. ISBN 978-3-8496-2203-9.

- Jorgensen 2000, p. 159.

- Tikhvinskiĭ, Sergeĭ Leonidovich and Leonard Sergeevich Perelomov (1981). China and her neighbours, from ancient times to the Middle Ages: a collection of essays. Progress Publishers. p. 124.

- von Le Coq, Albert. (1913). Chotscho: Facsimile-Wiedergaben der Wichtigeren Funde der Ersten Königlich Preussischen Expedition nach Turfan in Ost-Turkistan Archived 2016-09-15 at the Wayback Machine. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer (Ernst Vohsen), im Auftrage der Gernalverwaltung der Königlichen Museen aus Mitteln des Baessler-Institutes, Tafel 19 Archived 2016-09-15 at the Wayback Machine. (Accessed 3 September 2016).

- Gasparini, Mariachiara. "A Mathematic Expression of Art: Sino-Iranian and Uighur Textile Interactions and the Turfan Textile Collection in Berlin," in Rudolf G. Wagner and Monica Juneja (eds.), Transcultural Studies, Ruprecht-Karls Universität Heidelberg, No 1 (2014), pp. 134–163. ISSN 2191-6411. See also endnote #32. (Accessed 3 September 2016.)

- Hansen, Valerie (2012), The Silk Road: A New History, Oxford University Press, p. 98, ISBN 978-0-19-993921-3.

- Powell, William (2004). "Martial Arts". MacMillan Encyclopedia of Buddhism. 1. New York: MacMillan Reference USA. pp. 214–18. ISBN 0-02-865719-5.

- Broughton 1999, p. 9.

- Broughton 1999, p. 53.

- Broughton 1999, p. 56.

- Broughton 1999, p. 139.

- Broughton 1999, p. 2.

- McRae 2000.

- Lin 1996, p. 182.

- van Schaik, Sam (2015), Tibetan Zen, Discovering a Lost Tradition, Boston: Snow Lion, pp. 71–78

- Broughton 1999, p. 119.

- Cook 2003.

- Broughton 1999, pp. 2–3.

- Maguire 2001, p. 58.

- Watts 1962, p. 106.

- Lin 1996, p. 183.

- Dumoulin, Heisig & Knitter 2005, p. 86.

- Broughton 1999, p. 62.

- Broughton 1999, p. 132.

- Ferguson, pp 16-17

- Faure 1986, p. 187-198.

- Garfinkel 2006, p. 186.

- Wong 2001, p. Chapter 3.

- Haines 1995, p. Chapter 3.

- Shaikh Awab & Sutton 2006.

- Edou 1996, p. 32, p.181 n.20.

- Watts 1958, p. 32.

- Dumoulin, Heisig & Knitter 2005, p. 85.

- Dumoulin, Heisig & Knitter 2005, p. 102.

- Broughton 1999, pp. 9, 66.

- Red Pine 1989, p. 3, emphasis added.

- Dumoulin, Heisig & Knitter 2005, p. 96.

- Broughton 1999, p. 67–68.

- Dumoulin, Heisig & Knitter 2005, p. 52.

- Suzuki 1932, Preface.

- Kohn 1991, p. 125.

- Sutton 1991, p. 1.

- Suzuki 1932, XLII.

- Suzuki 1932, XI(a).

- Suzuki 1932, XVI.

- Suzuki 1932, IX.

- Suzuki 1932, VIII.

- Dumoulin 1993, p. 37.

- Cole 2009, p. 73–114.

- Yampolski 2003, p. 5-6.

- Suzuki 1949, p. 168.

- Chang 1967.

- Suzuki 1948, p. 50.

- Diener & friends 1991, p. 266.

- McRae 2003, p. 24.

- McRae 2003, p. 25.

- Chaline 2003, pp. 26–27.

- Dumoulin, Heisig & Knitter 2005, p. 89-90.

- Dumoulin, Heisig & Knitter 2005, p. 90.

- Acharya 2017.

- See Dani, AH, 'Some Early Buddhist Texts from Taxila and Peshawar Valley', Paper, Lahore SAS, 1983; and 'Short History of Pakistan' Vol 1, original 1967, rev ed 1992, and 'History of the Northern Areas of Pakistan' ed Lahore: Sang e Meel, 2001

- Eitel & Takakuwa 1904.

- Faure 1986.

- Buswell, pp. 57, 130.

- Broughton 1999, p. 55.

- Broughton 1999, p. 138.

- Shahar 2008, pp. 165–173.

- Ryuchi 1986.

- Henning 1994.

- Henning & Green 2001, p. 129.

Sources

Printed sources

- Broughton, Jeffrey L. (1999), The Bodhidharma Anthology: The Earliest Records of Zen, Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-21972-4

- Buswell, Robert E. (ed.), Encyclopedia of Buddhism, 1, Macmillan, ISBN 0-02-865718-7

- Chaline, Eric (2003), The Book of Zen: The Path to Inner Peace, Barron's Educational Series, ISBN 0-7641-5598-9

- Chang, Chung-Yuan (1967), "Ch'an Buddhism: Logical and Illogical", Philosophy East and West, Philosophy East and West, Vol. 17, No. 1/4, 17 (1/4): 37–49, doi:10.2307/1397043, JSTOR 1397043, archived from the original on 2011-05-24, retrieved 2006-12-01

- Cole, Alan (2009), Fathering Your Father: The Zen of Fabrication in Tang Buddhism, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-25485-5

- Cook, Francis Dojun (2003), Transmitting the Light: Zen Master's Keizan's Denkoroku, Boston: Wisdom Publications

- Diener, Michael S.; friends (1991), The Shambhala Dictionary of Buddhism and Zen, Boston: Shambhala

- Dumoulin, Heinrich (1993), "Early Chinese Zen Reexamined: A Supplement to Zen Buddhism: A History" (PDF), Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, 20 (1): 31–53, ISSN 0304-1042, archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-04.

- Dumoulin, Heinrich; Heisig, James; Knitter, Paul F. (2005). Zen Buddhism: India and China. World Wisdom, Inc. ISBN 978-0-941532-89-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Edou, Jérôme (1996), Machig Labdrön and the Foundations of Chöd, Snow Lion Publications, ISBN 978-1-55939-039-2

- Eitel, Ernest J.; Takakuwa, K. (1904), Hand-book of Chinese Buddhism: Being a Sanskrit-Chinese Dictionary with Vocabularies of Buddhist terms (Second ed.), Tokyo, Japan: Sanshusha, p. 33

- Faure, Bernard (1986), "Bodhidharma as Textual and Religious Paradigm", History of Religions, 25 (3): 187–198, doi:10.1086/463039

- Ferguson, Andrew. Zen's Chinese Heritage: The Masters and their Teachings. Somerville: Wisdom Publications, 2000. ISBN 0-86171-163-7.

- Garfinkel, Perry (2006), Buddha or Bust, Harmony Books, ISBN 978-1-4000-8217-9

- Goodman, Steven D.; Davidson, Ronald M. (1992), Tibetan Buddhism, SUNY Press

- Haines, Bruce (1995), Karate's history and traditions, Charles E. Tuttle Publishing Co., Inc, ISBN 0-8048-1947-5

- Henning, Stanley (1994), "Ignorance, Legend and Taijiquan" (PDF), Journal of the Chenstyle Taijiquan Research Association of Hawaii, 2 (3): 1–7, archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-02-23, retrieved 2019-10-19

- Henning, Stan; Green, Tom (2001), Folklore in the Martial Arts. In: Green, Thomas A., "Martial Arts of the World: An Encyclopedia", Santa Barbara, Calif: ABC-CLIO

- Jorgensen, John (2000), "Bodhidharma", in Johnston, William M. (ed.), Encyclopedia of Monasticism: A-L, Taylor & Francis

- Kambe, Tstuomu (2012), Bodhidharma. A collection of stories from Chinese literature (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-11-06, retrieved 2011-11-23

- Kohn, Michael H., ed. (1991), The Shambhala Dictionary of Buddhism and Zen, Boston: Shambhala.

- Lin, Boyuan (1996), Zhōngguó wǔshù shǐ 中國武術史, Taipei 臺北: Wǔzhōu chūbǎnshè 五洲出版社

- Macmillan (publisher) (2003), Encyclopedia of Buddhism (Volume One), MacMillan

- Maguire, Jack (2001), Essential Buddhism, New York: Pocket Books, ISBN 0-671-04188-6

- McRae, John R. (2000), "The Antecedents of Encounter Dialogue in Chinese Ch'an Buddhism", in Heine, Steven; Wright, Dale S. (eds.), The Kōan: Texts and Contexts in Zen Buddhism, Oxford University Press.

- McRae, John (2003), Seeing Through Zen. Encounter, Transformation, and Genealogy in Chinese Chan Buddhism, The University Press Group Ltd, ISBN 978-0-520-23798-8

- Acharya, Raghu (2017), Shanon, Sidharth (ed.), Bodhidharma Retold - A Journey from Sailum to Shaolin, New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120841529

- Red Pine, ed. (1989), The Zen Teaching of Bodhidharma: A Bilingual Edition, New York: North Point Press, ISBN 0-86547-399-4.

- Ryuchi, Matsuda 松田隆智 (1986), Zhōngguó wǔshù shǐlüè 中國武術史略 (in Chinese), Taipei 臺北: Danqing tushu

- Shahar, Meir (2008), The Shaolin Monastery: history, religion, and the Chinese martial arts, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 978-0-8248-3110-3.

- Shaikh Awab, Zainal Abidin; Sutton, Nigel (2006), Silat Tua: The Malay Dance Of Life, Kuala Lumpur: Azlan Ghanie Sdn Bhd, ISBN 978-983-42328-0-1

- Soothill, William Edward; Hodous, Lewis (1995), A Dictionary of Chinese Buddhist Terms (PDF), London: RoutledgeCurzon, archived from the original (PDF) on March 3, 2014

- Sutton, Florin Giripescu (1991), Existence and Enlightenment in the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra: A Study in the Ontology and Epistemology of the Yogācāra School of Mahāyāna Buddhism, Albany: State University of New York Press, ISBN 0-7914-0172-3.

- Suzuki, D.T., ed. (1932), The Lankavatara Sutra: A Mahayana Text.

- Suzuki, D.T. (1948), Manual of Zen Buddhism (PDF).

- Suzuki, D.T. (1949), Essays in Zen Buddhism, New York: Grove Press, ISBN 0-8021-5118-3

- Watts, Alan W. (1962), The Way of Zen, Great Britain: Pelican books, p. 106, ISBN 0-14-020547-0

- Watts, Alan (1958), The Spirit of Zen, New York: Grove Press.

- Williams, Paul. Mahayana Buddhism: The Doctrinal Foundations. ISBN 0-415-02537-0.

- Wong, Kiew Kit (2001), The Art of Shaolin Kungfu, Tuttle Publishing, ISBN 0-8048-3439-3

- Yampolski, Philip (2003), Chan. A Historical Sketch. In: Buddhist Spirituality. Later China, Korea, Japan and the Modern World; edited by Takeuchi Yoshinori, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass

- Zvelebil, Kamil V. (1987), "The Sound of the One Hand", Journal of the American Oriental Society, Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 107, No. 1, 107 (1): 125–126, doi:10.2307/602960, JSTOR 602960.

- 金实秋. Sino-Japanese-Korean Statue Dictionary of Bodhidharma (中日韩达摩造像图典). 宗教文化出版社, 2007–07. ISBN 7-80123-888-5

Web sources

- Masato Tojo, Zen Buddhism and Persian Culture

- Emmanuel Francis (2011), The Genealogy of the Pallavas: From Brahmins to Kings, Religions of South Asia, Vol. 5, No. 1/5.2 (2011)

- "The Committee of Western Bhikshunis". thubtenchodron.org.

- Zen Nun. "WOMEN IN ZEN BUDDHISM: Chinese Bhiksunis in the Ch'an Tradition". geocities.com. Archived from the original on 27 October 2009.

- Taishō Shinshū Daizōkyō, Vol. 50, No. 2060 Archived 2008-06-05 at the Wayback Machine, p. 551c 06(02)

- Denkoroku Archived September 1, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Simon Child. "In The Spirit of Chan". Western Chan Fellowship.

- Taishō Shinshū Daizōkyō, Vol. 85, No. 2837 Archived 2008-06-05 at the Wayback Machine, p. 1285b 17(05)

Further reading

- Broughton, Jeffrey L. (1999), The Bodhidharma Anthology: The Earliest Records of Zen, Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-21972-4

- Red Pine, ed. (1989), The Zen Teaching of Bodhidharma: A Bilingual Edition, New York: North Point Press, ISBN 0-86547-399-4

- McRae, John (2003), Seeing Through Zen. Encounter, Transformation, and Genealogy in Chinese Chan Buddhism, The University Press Group Ltd, ISBN 978-0-520-23798-8

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bodhidharma. |

- Essence of Mahayana Practice By Bodhidharma, with annotations. Also known as "The Outline of Practice." translated by Chung Tai Translation Committee

- Bodhidharma

| Buddhist titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Prajñādhara |

Lineage of Zen Buddhist patriarchs | Succeeded by Huike |