Sound film

A sound film is a motion picture with synchronized sound, or sound technologically coupled to image, as opposed to a silent film. The first known public exhibition of projected sound films took place in Paris in 1900, but decades passed before sound motion pictures were made commercially practical. Reliable synchronization was difficult to achieve with the early sound-on-disc systems, and amplification and recording quality were also inadequate. Innovations in sound-on-film led to the first commercial screening of short motion pictures using the technology, which took place in 1923.

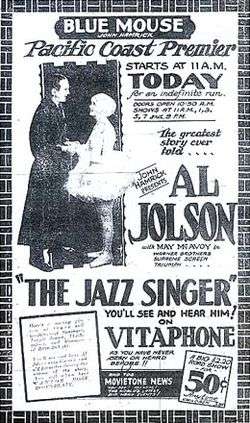

The primary steps in the commercialization of sound cinema were taken in the mid- to late 1920s. At first, the sound films which included synchronized dialogue, known as "talking pictures", or "talkies", were exclusively shorts. The earliest feature-length movies with recorded sound included only music and effects. The first feature film originally presented as a talkie was The Jazz Singer, released in October 1927. A major hit, it was made with Vitaphone, which was at the time the leading brand of sound-on-disc technology. Sound-on-film, however, would soon become the standard for talking pictures.

By the early 1930s, the talkies were a global phenomenon. In the United States, they helped secure Hollywood's position as one of the world's most powerful cultural/commercial centers of influence (see Cinema of the United States). In Europe (and, to a lesser degree, elsewhere), the new development was treated with suspicion by many filmmakers and critics, who worried that a focus on dialogue would subvert the unique aesthetic virtues of soundless cinema. In Japan, where the popular film tradition integrated silent movie and live vocal performance, talking pictures were slow to take root. Conversely, in India, sound was the transformative element that led to the rapid expansion of the nation's film industry.

History

Early steps

The idea of combining motion pictures with recorded sound is nearly as old as the concept of cinema itself. On February 27, 1888, a couple of days after photographic pioneer Eadweard Muybridge gave a lecture not far from the laboratory of Thomas Edison, the two inventors met privately. Muybridge later claimed that on this occasion, six years before the first commercial motion picture exhibition, he proposed a scheme for sound cinema that would combine his image-casting zoopraxiscope withholding Edison's recorded-sound technology.[2] No agreement was reached, but within a year Edison commissioned the development of the Kinetoscope, essentially a "peep-show" system, as a visual complement to his cylinder phonograph. The two devices were brought together as the Kinetophone in 1895, but individual, cabinet viewing of motion pictures was soon to be outmoded by successes in film projection.[3] In 1899, a projected sound-film system known as Cinemacrophonograph or Phonorama, based primarily on the work of Swiss-born inventor François Dussaud, was exhibited in Paris; similar to the Kinetophone, the system required individual use of earphones.[4] An improved cylinder-based system, Phono-Cinéma-Théâtre, was developed by Clément-Maurice Gratioulet and Henri Lioret of France, allowing short films of theater, opera, and ballet excerpts to be presented at the Paris Exposition in 1900. These appear to be the first publicly exhibited films with projection of both image and recorded sound. Phonorama and yet another sound-film system—Théâtroscope—were also presented at the Exposition.[5]

Three major problems persisted, leading to motion pictures and sound recording largely taking separate paths for a generation. The primary issue was synchronization: pictures and sound were recorded and played back by separate devices, which were difficult to start and maintain in tandem.[6] Sufficient playback volume was also hard to achieve. While motion picture projectors soon allowed film to be shown to large theater audiences, audio technology before the development of electric amplification could not project satisfactorily to fill large spaces. Finally, there was the challenge of recording fidelity. The primitive systems of the era produced sound of very low quality unless the performers were stationed directly in front of the cumbersome recording devices (acoustical horns, for the most part), imposing severe limits on the sort of films that could be created with live-recorded sound.[7]

Cinematic innovators attempted to cope with the fundamental synchronization problem in a variety of ways. An increasing number of motion picture systems relied on gramophone records—known as sound-on-disc technology. The records themselves were often referred to as "Berliner discs", after one of the primary inventors in the field, German-American Emile Berliner. In 1902, Léon Gaumont demonstrated his sound-on-disc Chronophone, involving an electrical connection he had recently patented, to the French Photographic Society.[8] Four years later, Gaumont introduced the Elgéphone, a compressed-air amplification system based on the Auxetophone, developed by British inventors Horace Short and Charles Parsons.[9] Despite high expectations, Gaumont's sound innovations had only limited commercial success. Despite some improvements, they still did not satisfactorily address the three basic issues with sound film and were expensive as well. For some years, American inventor E. E. Norton's Cameraphone was the primary competitor to the Gaumont system (sources differ on whether the Cameraphone was disc- or cylinder-based); it ultimately failed for many of the same reasons that held back the Chronophone.[10]

In 1913, Edison introduced a new cylinder-based synch-sound apparatus known, just like his 1895 system, as the Kinetophone. Instead of films being shown to individual viewers in the Kinetoscope cabinet, they were now projected onto a screen. The phonograph was connected by an intricate arrangement of pulleys to the film projector, allowing—under ideal conditions—for synchronization. However, conditions were rarely ideal, and the new, improved Kinetophone was retired after little more than a year.[11] By the mid-1910s, the groundswell in commercial sound motion picture exhibition had subsided.[10] Beginning in 1914, The Photo-Drama of Creation, promoting Jehovah's Witnesses' conception of humankind's genesis, was screened around the United States: eight hours worth of projected visuals involving both slides and live action, synchronized with separately recorded lectures and musical performances played back on phonograph.[12]

Meanwhile, innovations continued on another significant front. In 1900, as part of the research he was conducting on the photophone, the German physicist Ernst Ruhmer recorded the fluctuations of the transmitting arc-light as varying shades of light and dark bands onto a continuous roll of photographic film. He then determined that he could reverse the process and reproduce the recorded sound from this photographic strip by shining a bright light through the running filmstrip, with the resulting varying light illuminating a selenium cell. The changes in brightness caused a corresponding change to the selenium's resistance to electrical currents, which was used to modulate the sound produced in a telephone receiver. He called this invention the photographophone,[13] which he summarized as: "It is truly a wonderful process: sound becomes electricity, becomes light, causes chemical actions, becomes light and electricity again, and finally sound."[14]

Ruhmer began a correspondence with the French-born, London-based Eugene Lauste,[15] who had worked at Edison's lab between 1886 and 1892. In 1907, Lauste was awarded the first patent for sound-on-film technology, involving the transformation of sound into light waves that are photographically recorded direct onto celluloid. As described by historian Scott Eyman,

It was a double system, that is, the sound was on a different piece of film from the picture.... In essence, the sound was captured by a microphone and translated into light waves via a light valve, a thin ribbon of sensitive metal over a tiny slit. The sound reaching this ribbon would be converted into light by the shivering of the diaphragm, focusing the resulting light waves through the slit, where it would be photographed on the side of the film, on a strip about a tenth of an inch wide.[16]

In 1908, Lauste purchased a photographophone from Ruhmer, with the intention of perfecting the device into a commercial product.[17] Though sound-on-film would eventually become the universal standard for synchronized sound cinema. Lauste never successfully exploited his innovations, which came to an effective dead end. In 1914, Finnish inventor Eric Tigerstedt was granted German patent 309,536 for his sound-on-film work; that same year, he apparently demonstrated a film made with the process to an audience of scientists in Berlin.[18] Hungarian engineer Denes Mihaly submitted his sound-on-film Projectofon concept to the Royal Hungarian Patent Court in 1918; the patent award was published four years later.[19] Whether sound was captured on cylinder, disc, or film, none of the available technology was adequate for big-league commercial purposes, and for many years the heads of the major Hollywood film studios saw little benefit in producing sound motion pictures.[20]

Crucial innovations

A number of technological developments contributed to making sound cinema commercially viable by the late 1920s. Two involved contrasting approaches to synchronized sound reproduction, or playback:

Advanced sound-on-film

In 1919, American inventor Lee De Forest was awarded several patents that would lead to the first optical sound-on-film technology with commercial application. In De Forest's system, the sound track was photographically recorded onto the side of the strip of motion picture film to create a composite, or "married", print. If proper synchronization of sound and picture was achieved in recording, it could be absolutely counted on in playback. Over the next four years, he improved his system with the help of equipment and patents licensed from another American inventor in the field, Theodore Case.[21]

At the University of Illinois, Polish-born research engineer Joseph Tykociński-Tykociner was working independently on a similar process. On June 9, 1922, he gave the first reported U.S. demonstration of a sound-on-film motion picture to members of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers.[22] As with Lauste and Tigerstedt, Tykociner's system would never be taken advantage of commercially; however, De Forest's soon would.

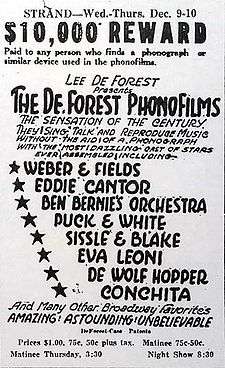

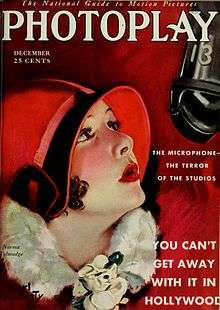

On April 15, 1923, at the New York City's Rivoli Theater took place the first commercial screening of motion pictures with sound-on-film, which would become the future standard. It consisted of a set of short film varying in length and featuring some of the most popular stars of the 1920s (including Eddie Cantor, Harry Richman, Sophie Tucker, and George Jessel among others) doing stage performances such as vaudevilles, musical acts, and speeches which accompanied the screening of the silent feature film Bella Donna.[23] All of them were presented under the banner of De Forest Phonofilms.[24] The set included the 11-minute short film From far Seville starring Concha Piquer. In 2010, a copy of the tape was found in the U.S. Library of Congress, where is currently preserved.[25][26][27] Critics attending the event praised the novelty but not the sound quality which received negative reviews in general.[28] That June, De Forest entered into an extended legal battle with an employee, Freeman Harrison Owens, for title to one of the crucial Phonofilm patents. Although De Forest ultimately won the case in the courts, Owens is today recognized as a central innovator in the field.[29] The following year, De Forest's studio released the first commercial dramatic film shot as a talking picture—the two-reeler Love's Old Sweet Song, directed by J. Searle Dawley and featuring Una Merkel.[30] However, phonofilm's stock in trade was not original dramas but celebrity documentaries, popular music acts, and comedy performances. President Calvin Coolidge, opera singer Abbie Mitchell, and vaudeville stars such as Phil Baker, Ben Bernie, Eddie Cantor and Oscar Levant appeared in the firm's pictures. Hollywood remained suspicious, even fearful, of the new technology. As Photoplay editor James Quirk put it in March 1924, "Talking pictures are perfected, says Dr. Lee De Forest. So is castor oil."[31] De Forest's process continued to be used through 1927 in the United States for dozens of short Phonofilms; in the UK it was employed a few years longer for both shorts and features by British Sound Film Productions, a subsidiary of British Talking Pictures, which purchased the primary Phonofilm assets. By the end of 1930, the Phonofilm business would be liquidated.[32]

In Europe, others were also working on the development of sound-on-film. In 1919, the same year that DeForest received his first patents in the field, three German inventors, Josef Engl (1893–1942), Hans Vogt (1890–1979), and Joseph Massolle (1889–1957), patented the Tri-Ergon sound system. On September 17, 1922, the Tri-Ergon group gave a public screening of sound-on-film productions—including a dramatic talkie, Der Brandstifter (The Arsonist) —before an invited audience at the Alhambra Kino in Berlin.[33] By the end of the decade, Tri-Ergon would be the dominant European sound system. In 1923, two Danish engineers, Axel Petersen and Arnold Poulsen, patented a system that recorded sound on a separate filmstrip running parallel with the image reel. Gaumont licensed the technology and briefly put it to commercial use under the name Cinéphone.[34]

Domestic competition, however, eclipsed Phonofilm. By September 1925, De Forest and Case's working arrangement had fallen through. The following July, Case joined Fox Film, Hollywood's third largest studio, to found the Fox-Case Corporation. The system developed by Case and his assistant, Earl Sponable, given the name Movietone, thus became the first viable sound-on-film technology controlled by a Hollywood movie studio. The following year, Fox purchased the North American rights to the Tri-Ergon system, though the company found it inferior to Movietone and virtually impossible to integrate the two different systems to advantage.[35] In 1927, as well, Fox retained the services of Freeman Owens, who had particular expertise in constructing cameras for synch-sound film.[36]

Advanced sound-on-disc

Parallel with improvements in sound-on-film technology, a number of companies were making progress with systems that recorded movie sound on phonograph discs. In sound-on-disc technology from the era, a phonograph turntable is connected by a mechanical interlock to a specially modified film projector, allowing for synchronization. In 1921, the Photokinema sound-on-disc system developed by Orlando Kellum was employed to add synchronized sound sequences to D. W. Griffith's failed silent film Dream Street. A love song, performed by star Ralph Graves, was recorded, as was a sequence of live vocal effects. Apparently, dialogue scenes were also recorded, but the results were unsatisfactory and the film was never publicly screened incorporating them. On May 1, 1921, Dream Street was re-released, with love song added, at New York City's Town Hall theater, qualifying it—however haphazardly—as the first feature-length film with a live-recorded vocal sequence.[37] There would be no others for more than six years.

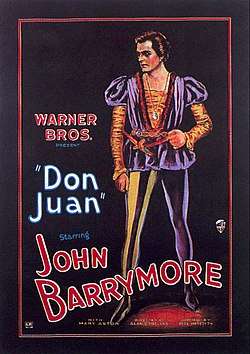

In 1925, Sam Warner of Warner Bros., then a small Hollywood studio with big ambitions, saw a demonstration of the Western Electric sound-on-disc system and was sufficiently impressed to persuade his brothers to agree to experiment with using this system at New York City's Vitagraph Studios, which they had recently purchased. The tests were convincing to the Warner Brothers, if not to the executives of some other picture companies who witnessed them. Consequently, in April 1926 the Western Electric Company entered into a contract with Warner Brothers and W. J. Rich, a financier, giving them an exclusive license for recording and reproducing sound pictures under the Western Electric system. To exploit this license the Vitaphone Corporation was organized with Samuel L. Warner as its president.[38][39] Vitaphone, as this system was now called, was publicly introduced on August 6, 1926, with the premiere of Don Juan; the first feature-length movie to employ a synchronized sound system of any type throughout, its soundtrack contained a musical score and added sound effects, but no recorded dialogue—in other words, it had been staged and shot as a silent film. Accompanying Don Juan, however, were eight shorts of musical performances, mostly classical, as well as a four-minute filmed introduction by Will H. Hays, president of the Motion Picture Association of America, all with live-recorded sound. These were the first true sound films exhibited by a Hollywood studio.[40] Warner Bros.' The Better 'Ole, technically similar to Don Juan, followed in October.[41]

Sound-on-film would ultimately win out over sound-on-disc because of a number of fundamental technical advantages:

- Synchronization: no interlock system was completely reliable, and a projectionist's error, or an inexactly repaired film break, or a defect in the soundtrack disc could result in the sound becoming seriously and irrecoverably out of sync with the picture

- Editing: discs could not be directly edited, severely limiting the ability to make alterations in their accompanying films after the original release cut

- Distribution: phonograph discs added expense and complication to film distribution

- Wear and tear: the physical process of playing the discs degraded them, requiring their replacement after approximately twenty screenings[42]

Nonetheless, in the early years, sound-on-disc had the edge over sound-on-film in two substantial ways:

- Production and capital cost: it was generally less expensive to record sound onto disc than onto film and the exhibition systems—turntable/interlock/projector—were cheaper to manufacture than the complex image-and-audio-pattern-reading projectors required by sound-on-film

- Audio quality: phonograph discs, Vitaphone's in particular, had superior dynamic range to most sound-on-film processes of the day, at least during the first few playings; while sound-on-film tended to have better frequency response, this was outweighed by greater distortion and noise[43][44]

As sound-on-film technology improved, both of these disadvantages were overcome.

The third crucial set of innovations marked a major step forward in both the live recording of sound and its effective playback:

Fidelity electronic recording and amplification

In 1913, Western Electric, the manufacturing division of AT&T, acquired the rights to the de Forest audion, the forerunner of the triode vacuum tube. Over the next few years they developed it into a predictable and reliable device that made electronic amplification possible for the first time. Western Electric then branched-out into developing uses for the vacuum tube including public address systems and an electrical recording system for the recording industry. Beginning in 1922, the research branch of Western Electric began working intensively on recording technology for both sound-on-disc and sound-on film synchronised sound systems for motion-pictures.

The engineers working on the sound-on-disc system were able to draw on expertise that Western Electric already had in electrical disc recording and were thus able to make faster initial progress. The main change required was to increase the playing time of the disc so that it could match that of a standard 1,000 ft (300 m) reel of 35 mm film. The chosen design used a disc nearly 16 inches (about 40 cm) in diameter rotating at 33 1/3 rpm. This could play for 11 minutes, the running time of 1000 ft of film at 90 ft/min (24 frames/s).[45] Because of the larger diameter the minimum groove velocity of 70 ft/min (14 inches or 356 mm/s) was only slightly less than that of a standard 10-inch 78 rpm commercial disc. In 1925, the company publicly introduced a greatly improved system of electronic audio, including sensitive condenser microphones and rubber-line recorders (named after the use of a rubber damping band for recording with better frequency response onto a wax master disc[46]). That May, the company licensed entrepreneur Walter J. Rich to exploit the system for commercial motion pictures; he founded Vitagraph, in which Warner Bros. acquired a half interest, just one month later.[47] In April 1926, Warners signed a contract with AT&T for exclusive use of its film sound technology for the redubbed Vitaphone operation, leading to the production of Don Juan and its accompanying shorts over the following months.[38] During the period when Vitaphone had exclusive access to the patents, the fidelity of recordings made for Warners films was markedly superior to those made for the company's sound-on-film competitors. Meanwhile, Bell Labs—the new name for the AT&T research operation—was working at a furious pace on sophisticated sound amplification technology that would allow recordings to be played back over loudspeakers at theater-filling volume. The new moving-coil speaker system was installed in New York's Warners Theatre at the end of July and its patent submission, for what Western Electric called the No. 555 Receiver, was filed on August 4, just two days before the premiere of Don Juan.[44][48]

Late in the year, AT&T/Western Electric created a licensing division, Electrical Research Products Inc. (ERPI), to handle rights to the company's film-related audio technology. Vitaphone still had legal exclusivity, but having lapsed in its royalty payments, effective control of the rights was in ERPI's hands. On December 31, 1926, Warners granted Fox-Case a sublicense for the use of the Western Electric system; in exchange for the sublicense, both Warners and ERPI received a share of Fox's related revenues. The patents of all three concerns were cross-licensed.[49] Superior recording and amplification technology was now available to two Hollywood studios, pursuing two very different methods of sound reproduction. The new year would finally see the emergence of sound cinema as a significant commercial medium.

Triumph of the "talkies"

In February 1927, an agreement was signed by five leading Hollywood movie companies: Famous Players-Lasky (soon to be part of Paramount), Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Universal, First National, and Cecil B. DeMille's small but prestigious Producers Distributing Corporation (PDC). The five studios agreed to collectively select just one provider for sound conversion, and then waited to see what sort of results the front-runners came up with.[50] In May, Warner Bros. sold back its exclusivity rights to ERPI (along with the Fox-Case sublicense) and signed a new royalty contract similar to Fox's for use of Western Electric technology. Fox and Warners pressed forward with sound cinema, moving in different directions both technologically and commercially: Fox moved into newsreels and then scored dramas, while Warners concentrated on talking features. Meanwhile, ERPI sought to corner the market by signing up the five allied studios.[51]

The big sound film sensations of the year all took advantage of preexisting celebrity. On May 20, 1927, at New York City's Roxy Theater, Fox Movietone presented a sound film of the takeoff of Charles Lindbergh's celebrated flight to Paris, recorded earlier that day. In June, a Fox sound newsreel depicting his return welcomes in New York City and Washington, D.C., was shown. These were the two most acclaimed sound motion pictures to date.[52] In May, as well, Fox had released the first Hollywood fiction film with synchronized dialogue: the short They're Coming to Get Me, starring comedian Chic Sale.[53] After rereleasing a few silent feature hits, such as Seventh Heaven, with recorded music, Fox came out with its first original Movietone feature on September 23: Sunrise, by acclaimed German director F. W. Murnau. As with Don Juan, the film's soundtrack consisted of a musical score and sound effects (including, in a couple of crowd scenes, "wild", nonspecific vocals).[54]

Then, on October 6, 1927, Warner Bros.' The Jazz Singer premiered. It was a smash box office success for the mid-level studio, earning a total of $2.625 million in the United States and abroad, almost a million dollars more than the previous record for a Warners film.[55] Produced with the Vitaphone system, most of the film does not contain live-recorded audio, relying, like Sunrise and Don Juan, on a score and effects. When the movie's star, Al Jolson, sings, however, the film shifts to sound recorded on the set, including both his musical performances and two scenes with ad-libbed speech—one of Jolson's character, Jakie Rabinowitz (Jack Robin), addressing a cabaret audience; the other an exchange between him and his mother. The "natural" sounds of the settings were also audible.[56] Though the success of The Jazz Singer was due largely to Jolson, already established as one of U.S. biggest music stars, and its limited use of synchronized sound hardly qualified it as an innovative sound film (let alone the "first"), the movie's profits were proof enough to the industry that the technology was worth investing in.[57]

The development of commercial sound cinema had proceeded in fits and starts before The Jazz Singer, and the film's success did not change things overnight. Influential gossip columnist Louella Parsons reaction to The Jazz Singer was badly off the mark: "I have no fear that the screeching sound film will ever disturb our theaters," while MGM head of production Irving Thalberg called the film "a good gimmick, but that's all it was."[58] Not until May 1928 did the group of four big studios (PDC had dropped out of the alliance), along with United Artists and others, sign with ERPI for conversion of production facilities and theaters for sound film. It was a daunting commitment; revamping a single theater cost as much as $15,000 (the equivalent of $220,000 in 2019), and there were more than 20,000 movie theaters in the United States. By 1930, only half of the theaters had been wired for sound.[59]

Initially, all ERPI-wired theaters were made Vitaphone-compatible; most were equipped to project Movietone reels as well.[60] However, even with access to both technologies, most of the Hollywood companies remained slow to produce talking features of their own. No studio besides Warner Bros. released even a part-talking feature until the low-budget-oriented Film Booking Offices of America (FBO) premiered The Perfect Crime on June 17, 1928, eight months after The Jazz Singer.[61] FBO had come under the effective control of a Western Electric competitor, General Electric's RCA division, which was looking to market its new sound-on-film system, Photophone. Unlike Fox-Case's Movietone and De Forest's Phonofilm, which were variable-density systems, Photophone was a variable-area system—a refinement in the way the audio signal was inscribed on film that would ultimately become the standard. (In both sorts of systems, a specially-designed lamp, whose exposure to the film is determined by the audio input, is used to record sound photographically as a series of minuscule lines. In a variable-density process, the lines are of varying darkness; in a variable-area process, the lines are of varying width.) By October, the FBO-RCA alliance would lead to the creation of Hollywood's newest major studio, RKO Pictures.

Meanwhile, Warner Bros. had released three more talkies, all profitable, if not at the level of The Jazz Singer: In March, Tenderloin appeared; it was billed by Warners as the first feature in which characters spoke their parts, though only 15 of its 88 minutes had dialogue. Glorious Betsy followed in April, and The Lion and the Mouse (31 minutes of dialogue) in May.[62] On July 6, 1928, the first all-talking feature, Lights of New York, premiered. The film cost Warner Bros. only $23,000 to produce, but grossed $1.252 million, a record rate of return surpassing 5,000%. In September, the studio released another Al Jolson part-talking picture, The Singing Fool, which more than doubled The Jazz Singer's earnings record for a Warners movie.[63] This second Jolson screen smash demonstrated the movie musical's ability to turn a song into a national hit: inside of nine months, the Jolson number "Sonny Boy" had racked up 2 million record and 1.25 million sheet music sales.[64] September 1928 also saw the release of Paul Terry's Dinner Time, among the first animated cartoons produced with synchronized sound. Soon after he saw it, Walt Disney released his first sound picture, the Mickey Mouse short Steamboat Willie.[65]

Over the course of 1928, as Warner Bros. began to rake in huge profits due to the popularity of its sound films, the other studios quickened the pace of their conversion to the new technology. Paramount, the industry leader, put out its first talkie in late September, Beggars of Life; though it had just a few lines of dialogue, it demonstrated the studio's recognition of the new medium's power. Interference, Paramount's first all-talker, debuted in November.[66] The process known as "goat glanding" briefly became widespread: soundtracks, sometimes including a smatter of post-dubbed dialogue or song, were added to movies that had been shot, and in some cases released, as silents.[67] A few minutes of singing could qualify such a newly endowed film as a "musical." (Griffith's Dream Street had essentially been a "goat gland.") Expectations swiftly changed, and the sound "fad" of 1927 became standard procedure by 1929. In February 1929, sixteen months after The Jazz Singer's debut, Columbia Pictures became the last of the eight studios that would be known as "majors" during Hollywood's Golden Age to release its first part-talking feature, The Lone Wolf's Daughter.[68] In late May, the first all-color, all-talking feature, Warner Bros.' On with the Show!, premiered.[69]

Yet most American movie theaters, especially outside of urban areas, were still not equipped for sound: while the number of sound cinemas grew from 100 to 800 between 1928 and 1929, they were still vastly outnumbered by silent theaters, which had actually grown in number as well, from 22,204 to 22,544.[70] The studios, in parallel, were still not entirely convinced of the talkies' universal appeal—until mid-1930, the majority of Hollywood movies were produced in dual versions, silent as well as talking.[71] Though few in the industry predicted it, silent film as a viable commercial medium in the United States would soon be little more than a memory. Points West, a Hoot Gibson Western released by Universal Pictures in August 1929, was the last purely silent mainstream feature put out by a major Hollywood studio.[72]

Transition: Europe

The Jazz Singer had its European sound premiere at the Piccadilly Theatre in London on September 27, 1928.[73] According to film historian Rachael Low, "Many in the industry realized at once that a change to sound production was inevitable."[74] On January 16, 1929, the first European feature film with a synchronized vocal performance and recorded score premiered: the German production Ich küsse Ihre Hand, Madame (I Kiss Your Hand, Madame). Dialogueless, it contains only a few songs performed by Richard Tauber.[75] The movie was made with the sound-on-film system controlled by the German-Dutch firm Tobis, corporate heirs to the Tri-Ergon concern. With an eye toward commanding the emerging European market for sound film, Tobis entered into a compact with its chief competitor, Klangfilm, a joint subsidiary of Germany's two leading electrical manufacturers. Early in 1929, Tobis and Klangfilm began comarketing their recording and playback technologies. As ERPI began to wire theaters around Europe, Tobis-Klangfilm claimed that the Western Electric system infringed on the Tri-Ergon patents, stalling the introduction of American technology in many places.[76] Just as RCA had entered the movie business to maximize its recording system's value, Tobis also established its own production operations.[77]

During 1929, most of the major European filmmaking countries began joining Hollywood in the changeover to sound. Many of the trend-setting European talkies were shot abroad as production companies leased studios while their own were being converted or as they deliberately targeted markets speaking different languages. One of Europe's first two feature-length dramatic talkies was created in still a different sort of twist on multinational moviemaking: The Crimson Circle was a coproduction between director Friedrich Zelnik's Efzet-Film company and British Sound Film Productions (BSFP). In 1928, the film had been released as the silent Der Rote Kreis in Germany, where it was shot; English dialogue was apparently dubbed in much later using the De Forest Phonofilm process controlled by BSFP's corporate parent. It was given a British trade screening in March 1929, as was a part-talking film made entirely in the UK: The Clue of the New Pin, a British Lion production using the sound-on-disc British Photophone system. In May, Black Waters, a British and Dominions Film Corporation promoted as the first UK all-talker, received its initial trade screening; it had been shot completely in Hollywood with a Western Electric sound-on-film system. None of these pictures made much impact.[78]

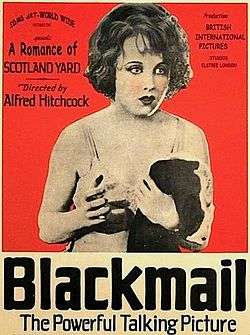

The first successful European dramatic talkie was the all-British Blackmail. Directed by twenty-nine-year-old Alfred Hitchcock, the movie had its London debut June 21, 1929. Originally shot as a silent, Blackmail was restaged to include dialogue sequences, along with a score and sound effects, before its premiere. A British International Pictures (BIP) production, it was recorded on RCA Photophone, General Electric having bought a share of AEG so they could access the Tobis-Klangfilm markets. Blackmail was a substantial hit; critical response was also positive—notorious curmudgeon Hugh Castle, for example, called it "perhaps the most intelligent mixture of sound and silence we have yet seen."[80]

On August 23, the modest-sized Austrian film industry came out with a talkie: G'schichten aus der Steiermark (Stories from Styria), an Eagle Film–Ottoton Film production.[81] On September 30, the first entirely German-made feature-length dramatic talkie, Das Land ohne Frauen (Land Without Women), premiered. A Tobis Filmkunst production, about one-quarter of the movie contained dialogue, which was strictly segregated from the special effects and music. The response was underwhelming.[82] Sweden's first talkie, Konstgjorda Svensson (Artificial Svensson), premiered on October 14. Eight days later, Aubert Franco-Film came out with Le Collier de la reine (The Queen's Necklace), shot at the Épinay studio near Paris. Conceived as a silent film, it was given a Tobis-recorded score and a single talking sequence—the first dialogue scene in a French feature. On October 31, Les Trois masques (The Three Masks) debuted; a Pathé-Natan film, it is generally regarded as the initial French feature talkie, though it was shot, like Blackmail, at the Elstree studio, just outside London. The production company had contracted with RCA Photophone and Britain then had the nearest facility with the system. The Braunberger-Richebé talkie La Route est belle (The Road Is Fine), also shot at Elstree, followed a few weeks later.[83]

Before the Paris studios were fully sound-equipped—a process that stretched well into 1930—a number of other early French talkies were shot in Germany.[84] The first all-talking German feature, Atlantik, had premiered in Berlin on October 28. Yet another Elstree-made movie, it was rather less German at heart than Les Trois masques and La Route est belle were French; a BIP production with a British scenarist and German director, it was also shot in English as Atlantic.[85] The entirely German Aafa-Film production It's You I Have Loved (Dich hab ich geliebt) opened three-and-a-half weeks later. It was not "Germany's First Talking Film", as the marketing had it, but it was the first to be released in the United States.[86]

In 1930, the first Polish talkies premiered, using sound-on-disc systems: Moralność pani Dulskiej (The Morality of Mrs. Dulska) in March and the all-talking Niebezpieczny romans (Dangerous Love Affair) in October.[88] In Italy, whose once vibrant film industry had become moribund by the late 1920s, the first talkie, La Canzone dell'amore (The Song of Love), also came out in October; within two years, Italian cinema would be enjoying a revival.[89] The first movie spoken in Czech debuted in 1930 as well, Tonka Šibenice (Tonka of the Gallows).[90] Several European nations with minor positions in the field also produced their first talking pictures—Belgium (in French), Denmark, Greece, and Romania.[91] The Soviet Union's robust film industry came out with its first sound features in December 1930: Dziga Vertov's nonfiction Enthusiasm had an experimental, dialogueless soundtrack; Abram Room's documentary Plan velikikh rabot (The Plan of the Great Works) had music and spoken voiceovers.[92] Both were made with locally developed sound-on-film systems, two of the two hundred or so movie sound systems then available somewhere in the world.[93] In June 1931, the Nikolai Ekk drama Putevka v zhizn (The Road to Life or A Start in Life), premiered as the Soviet Union's first true talking picture.[94]

Throughout much of Europe, conversion of exhibition venues lagged well behind production capacity, requiring talkies to be produced in parallel silent versions or simply shown without sound in many places. While the pace of conversion was relatively swift in Britain—with over 60 percent of theaters equipped for sound by the end of 1930, similar to the U.S. figure—in France, by contrast, more than half of theaters nationwide were still projecting in silence by late 1932.[95] According to scholar Colin G. Crisp, "Anxiety about resuscitating the flow of silent films was frequently expressed in the [French] industrial press, and a large section of the industry still saw the silent as a viable artistic and commercial prospect till about 1935."[96] The situation was particularly acute in the Soviet Union; as of May 1933, fewer than one out of every hundred film projectors in the country was as yet equipped for sound.[97]

Transition: Asia

During the 1920s and 1930s, Japan was one of the world's two largest producers of motion pictures, along with the United States. Though the country's film industry was among the first to produce both sound and talking features, the full changeover to sound proceeded much more slowly than in the West. It appears that the first Japanese sound film, Reimai (Dawn), was made in 1926 with the De Forest Phonofilm system.[99] Using the sound-on-disc Minatoki system, the leading Nikkatsu studio produced a pair of talkies in 1929: Taii no musume (The Captain's Daughter) and Furusato (Hometown), the latter directed by Kenji Mizoguchi. The rival Shochiku studio began the successful production of sound-on-film talkies in 1931 using a variable-density process called Tsuchibashi.[100] Two years later, however, more than 80 percent of movies made in the country were still silents.[101] Two of the country's leading directors, Mikio Naruse and Yasujirō Ozu, did not make their first sound films until 1935 and 1936, respectively.[102] As late as 1938, over a third of all movies produced in Japan were shot without dialogue.[101]

The enduring popularity of the silent medium in Japanese cinema owed in great part to the tradition of the benshi, a live narrator who performed as accompaniment to a film screening. As director Akira Kurosawa later described, the benshi "not only recounted the plot of the films, they enhanced the emotional content by performing the voices and sound effects and providing evocative descriptions of events and images on the screen.... The most popular narrators were stars in their own right, solely responsible for the patronage of a particular theatre."[103] Film historian Mariann Lewinsky argues,

The end of silent film in the West and in Japan was imposed by the industry and the market, not by any inner need or natural evolution.... Silent cinema was a highly pleasurable and fully mature form. It didn't lack anything, least in Japan, where there was always the human voice doing the dialogues and the commentary. Sound films were not better, just more economical. As a cinema owner you didn't have to pay the wages of musicians and benshi any more. And a good benshi was a star demanding star payment.[104]

By the same token, the viability of the benshi system facilitated a gradual transition to sound—allowing the studios to spread out the capital costs of conversion and their directors and technical crews time to become familiar with the new technology.[105]

The Mandarin-language Gēnǚ hóng mǔdān (歌女紅牡丹, Singsong Girl Red Peony), starring Butterfly Wu, premiered as China's first feature talkie in 1930. By February of that year, production was apparently completed on a sound version of The Devil's Playground, arguably qualifying it as the first Australian talking motion picture; however, the May press screening of Commonwealth Film Contest prizewinner Fellers is the first verifiable public exhibition of an Australian talkie.[107] In September 1930, a song performed by Indian star Sulochana, excerpted from the silent feature Madhuri (1928), was released as a synchronized-sound short, the country's first.[108] The following year, Ardeshir Irani directed the first Indian talking feature, the Hindi-Urdu Alam Ara, and produced Kalidas, primarily in Tamil with some Telugu. Nineteen-thirty-one also saw the first Bengali-language film, Jamai Sasthi, and the first movie fully spoken in Telugu, Bhakta Prahlada.[109][110] In 1932, Ayodhyecha Raja became the first movie in which Marathi was spoken to be released (though Sant Tukaram was the first to go through the official censorship process); the first Gujarati-language film, Narsimha Mehta, and all-Tamil talkie, Kalava, debuted as well. The next year, Ardeshir Irani produced the first Persian-language talkie, Dukhtar-e-loor.[111] Also in 1933, the first Cantonese-language films were produced in Hong Kong—Sha zai dongfang (The Idiot's Wedding Night) and Liang xing (Conscience); within two years, the local film industry had fully converted to sound.[112] Korea, where pyonsa (or byun-sa) held a role and status similar to that of the Japanese benshi,[113] in 1935 became the last country with a significant film industry to produce its first talking picture: Chunhyangjeon (春香傳/춘향전) is based on the seventeenth-century pansori folktale "Chunhyangga", of which as many as fifteen film versions have been made through 2009.[114]

Consequences

Technology

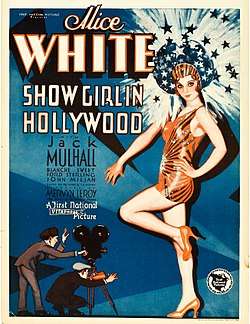

In the short term, the introduction of live sound recording caused major difficulties in production. Cameras were noisy, so a soundproofed cabinet was used in many of the earliest talkies to isolate the loud equipment from the actors, at the expense of a drastic reduction in the ability to move the camera. For a time, multiple-camera shooting was used to compensate for the loss of mobility and innovative studio technicians could often find ways to liberate the camera for particular shots. The necessity of staying within range of still microphones meant that actors also often had to limit their movements unnaturally. Show Girl in Hollywood (1930), from First National Pictures (which Warner Bros. had taken control of thanks to its profitable adventure into sound), gives a behind-the-scenes look at some of the techniques involved in shooting early talkies. Several of the fundamental problems caused by the transition to sound were soon solved with new camera casings, known as "blimps", designed to suppress noise and boom microphones that could be held just out of frame and moved with the actors. In 1931, a major improvement in playback fidelity was introduced: three-way speaker systems in which sound was separated into low, medium, and high frequencies and sent respectively to a large bass "woofer", a midrange driver, and a treble "tweeter."[115]

There were consequences, as well, for other technological aspects of the cinema. Proper recording and playback of sound required exact standardization of camera and projector speed. Before sound, 16 frames per second (fps) was the supposed norm, but practice varied widely. Cameras were often undercranked or overcranked to improve exposures or for dramatic effect. Projectors were commonly run too fast to shorten running time and squeeze in extra shows. Variable frame rate, however, made sound unlistenable, and a new, strict standard of 24 fps was soon established.[116] Sound also forced the abandonment of the noisy arc lights used for filming in studio interiors. The switch to quiet incandescent illumination in turn required a switch to more expensive film stock. The sensitivity of the new panchromatic film delivered superior image tonal quality and gave directors the freedom to shoot scenes at lower light levels than was previously practical.[116]

As David Bordwell describes, technological improvements continued at a swift pace: "Between 1932 and 1935, [Western Electric and RCA] created directional microphones, increased the frequency range of film recording, reduced ground noise ... and extended the volume range." These technical advances often meant new aesthetic opportunities: "Increasing the fidelity of recording ... heightened the dramatic possibilities of vocal timbre, pitch, and loudness."[117] Another basic problem—famously spoofed in the 1952 film Singin' in the Rain—was that some silent-era actors simply did not have attractive voices; though this issue was frequently overstated, there were related concerns about general vocal quality and the casting of performers for their dramatic skills in roles also requiring singing talent beyond their own. By 1935, rerecording of vocals by the original or different actors in postproduction, a process known as "looping", had become practical. The ultraviolet recording system introduced by RCA in 1936 improved the reproduction of sibilants and high notes.[118]

With Hollywood's wholesale adoption of the talkies, the competition between the two fundamental approaches to sound-film production was soon resolved. Over the course of 1930–31, the only major players using sound-on-disc, Warner Bros. and First National, changed over to sound-on-film recording. Vitaphone's dominating presence in sound-equipped theaters, however, meant that for years to come all of the Hollywood studios pressed and distributed sound-on-disc versions of their films alongside the sound-on-film prints.[119] Fox Movietone soon followed Vitaphone into disuse as a recording and reproduction method, leaving two major American systems: the variable-area RCA Photophone and Western Electric's own variable-density process, a substantial improvement on the cross-licensed Movietone.[120] Under RCA's instigation, the two parent companies made their projection equipment compatible, meaning films shot with one system could be screened in theaters equipped for the other.[121] This left one big issue—the Tobis-Klangfilm challenge. In May 1930, Western Electric won an Austrian lawsuit that voided protection for certain Tri-Ergon patents, helping bring Tobis-Klangfilm to the negotiating table.[122] The following month an accord was reached on patent cross-licensing, full playback compatibility, and the division of the world into three parts for the provision of equipment. As a contemporary report describes:

Tobis-Klangfilm has the exclusive rights to provide equipment for: Germany, Danzig, Austria, Hungary, Switzerland, Czechoslovakia, Holland, the Dutch Indies, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Bulgaria, Romania, Yugoslavia, and Finland. The Americans have the exclusive rights for the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, India, and Russia. All other countries, among them Italy, France, and England, are open to both parties.[123]

The agreement did not resolve all the patent disputes, and further negotiations were undertaken and concords signed over the course of the 1930s. During these years, as well, the American studios began abandoning the Western Electric system for RCA Photophone's variable-area approach—by the end of 1936, only Paramount, MGM, and United Artists still had contracts with ERPI.[124]

Labor

While the introduction of sound led to a boom in the motion picture industry, it had an adverse effect on the employability of a host of Hollywood actors of the time. Suddenly those without stage experience were regarded as suspect by the studios; as suggested above, those whose heavy accents or otherwise discordant voices had previously been concealed were particularly at risk. The career of major silent star Norma Talmadge effectively came to an end in this way. The celebrated German actor Emil Jannings returned to Europe. Moviegoers found John Gilbert's voice an awkward match with his swashbuckling persona, and his star also faded.[126] Audiences now seemed to perceive certain silent-era stars as old-fashioned, even those who had the talent to succeed in the sound era. The career of Harold Lloyd, one of the top screen comedians of the 1920s, declined precipitously.[127] Lillian Gish departed, back to the stage, and other leading figures soon left acting entirely: Colleen Moore, Gloria Swanson, and Hollywood's most famous performing couple, Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford.[128] As actress Louise Brooks suggested, there were other issues as well:

Studio heads, now forced into unprecedented decisions, decided to begin with the actors, the least palatable, the most vulnerable part of movie production. It was such a splendid opportunity, anyhow, for breaking contracts, cutting salaries, and taming the stars.... Me, they gave the salary treatment. I could stay on without the raise my contract called for, or quit, [Paramount studio chief B. P.] Schulberg said, using the questionable dodge of whether I'd be good for the talkies. Questionable, I say, because I spoke decent English in a decent voice and came from the theater. So without hesitation I quit.[129]

Buster Keaton was eager to explore the new medium, but when his studio, MGM, made the changeover to sound, he was quickly stripped of creative control. Though a number of Keaton's early talkies made impressive profits, they were artistically dismal.[130]

Several of the new medium's biggest attractions came from vaudeville and the musical theater, where performers such as Al Jolson, Eddie Cantor, Jeanette MacDonald, and the Marx Brothers were accustomed to the demands of both dialogue and song.[131] James Cagney and Joan Blondell, who had teamed on Broadway, were brought west together by Warner Bros. in 1930.[132] A few actors were major stars during both the silent and the sound eras: John Barrymore, Ronald Colman, Myrna Loy, William Powell, Norma Shearer, the comedy team of Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy, and Charlie Chaplin, whose City Lights (1931) and Modern Times (1936) employed sound almost exclusively for music and effects.[133] Janet Gaynor became a top star with the synch-sound but dialogueless Seventh Heaven and Sunrise, as did Joan Crawford with the technologically similar Our Dancing Daughters (1928).[134] Greta Garbo was the one non–native English speaker to retain Hollywood stardom on both sides of the great sound divide.[135] Silent film extra Clark Gable, who had received extensive voice training during his earlier stage career, went on to dominate the new medium for decades; similarly, English actor Boris Karloff, having appeared in dozens of silent films since 1919, found his star ascend in the sound era (though, ironically, it was a non-speaking role in 1931's Frankenstein that made this happen, but despite having a lisp, he found himself much in demand after). The new emphasis on speech also caused producers to hire many novelists, journalists, and playwrights with experience writing good dialogue. Among those who became Hollywood scriptwriters during the 1930s were Nathanael West, William Faulkner, Robert Sherwood, Aldous Huxley, and Dorothy Parker.[136]

As talking pictures emerged, with their prerecorded musical tracks, an increasing number of moviehouse orchestra musicians found themselves out of work.[137] More than just their position as film accompanists was usurped; according to historian Preston J. Hubbard, "During the 1920s live musical performances at first-run theaters became an exceedingly important aspect of the American cinema."[138] With the coming of the talkies, those featured performances—usually staged as preludes—were largely eliminated as well. The American Federation of Musicians took out newspaper advertisements protesting the replacement of live musicians with mechanical playing devices. One 1929 ad that appeared in the Pittsburgh Press features an image of a can labeled "Canned Music / Big Noise Brand / Guaranteed to Produce No Intellectual or Emotional Reaction Whatever" and reads in part:

Canned Music on Trial

This is the case of Art vs. Mechanical Music in theatres. The defendant stands accused in front of the American people of attempted corruption of musical appreciation and discouragement of musical education. Theatres in many cities are offering synchronised mechanical music as a substitute for Real Music. If the theatre-going public accepts this vitiation of its entertainment program a deplorable decline in the Art of Music is inevitable. Musical authorities know that the soul of the Art is lost in mechanization. It cannot be otherwise because the quality of music is dependent on the mood of the artist, upon the human contact, without which the essence of intellectual stimulation and emotional rapture is lost.[139]

By the following year, a reported 22,000 U.S. moviehouse musicians had lost their jobs.[140]

Commerce

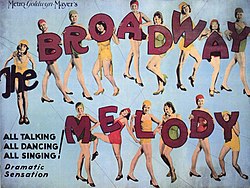

In September 1926, Jack L. Warner, head of Warner Bros., was quoted to the effect that talking pictures would never be viable: "They fail to take into account the international language of the silent pictures, and the unconscious share of each onlooker in creating the play, the action, the plot, and the imagined dialogue for himself."[141] Much to his company's benefit, he would be proven very wrong—between the 1927–28 and 1928–29 fiscal years, Warners' profits surged from $2 million to $14 million. Sound film, in fact, was a clear boon to all the major players in the industry. During that same twelve-month span, Paramount's profits rose by $7 million, Fox's by $3.5 million, and Loew's/MGM's by $3 million.[142] RKO, which did not even exist in September 1928 and whose parent production company, FBO, was in the Hollywood minor leagues, by the end of 1929 was established as one of America's leading entertainment businesses.[143] Fueling the boom was the emergence of an important new cinematic genre made possible by sound: the musical. Over sixty Hollywood musicals were released in 1929, and more than eighty the following year.[144]

Even as the Wall Street crash of October 1929 helped plunge the United States and ultimately the global economy into depression, the popularity of the talkies at first seemed to keep Hollywood immune. The 1929–30 exhibition season was even better for the motion picture industry than the previous, with ticket sales and overall profits hitting new highs. Reality finally struck later in 1930, but sound had clearly secured Hollywood's position as one of the most important industrial fields, both commercially and culturally, in the United States. In 1929, film box-office receipts comprised 16.6 percent of total spending by Americans on recreation; by 1931, the figure had reached 21.8 percent. The motion picture business would command similar figures for the next decade and a half.[145] Hollywood ruled on the larger stage, as well. The American movie industry—already the world's most powerful—set an export record in 1929 that, by the applied measure of total feet of exposed film, was 27 percent higher than the year before.[146] Concerns that language differences would hamper U.S. film exports turned out to be largely unfounded. In fact, the expense of sound conversion was a major obstacle to many overseas producers, relatively undercapitalized by Hollywood standards. The production of multiple versions of export-bound talkies in different languages (known as "Foreign Language Version"), as well as the production of the cheaper "International Sound Version", a common approach at first, largely ceased by mid-1931, replaced by post-dubbing and subtitling. Despite trade restrictions imposed in most foreign markets, by 1937, American films commanded about 70 percent of screen time around the globe.[147]

Just as the leading Hollywood studios gained from sound in relation to their foreign competitors, they did the same at home. As historian Richard B. Jewell describes, "The sound revolution crushed many small film companies and producers who were unable to meet the financial demands of sound conversion."[148] The combination of sound and the Great Depression led to a wholesale shakeout in the business, resulting in the hierarchy of the Big Five integrated companies (MGM, Paramount, Fox, Warners, RKO) and the three smaller studios also called "majors" (Columbia, Universal, United Artists) that would predominate through the 1950s. Historian Thomas Schatz describes the ancillary effects:

Because the studios were forced to streamline operations and rely on their own resources, their individual house styles and corporate personalities came into much sharper focus. Thus the watershed period from the coming of sound into the early Depression saw the studio system finally coalesce, with the individual studios coming to terms with their own identities and their respective positions within the industry.[149]

The other country in which sound cinema had an immediate major commercial impact was India. As one distributor of the period said, "With the coming of the talkies, the Indian motion picture came into its own as a definite and distinctive piece of creation. This was achieved by music."[150] From its earliest days, Indian sound cinema has been defined by the musical—Alam Ara featured seven songs; a year later, Indrasabha would feature seventy. While the European film industries fought an endless battle against the popularity and economic muscle of Hollywood, ten years after the debut of Alam Ara, over 90 percent of the films showing on Indian screens were made within the country.[151]

Most of India's early talkies were shot in Bombay, which remains the leading production center, but sound filmmaking soon spread across the multilingual nation. Within just a few weeks of Alam Ara's March 1931 premiere, the Calcutta-based Madan Pictures had released both the Hindi Shirin Farhad and the Bengali Jamai Sasthi.[152] The Hindustani Heer Ranjha was produced in Lahore, Punjab, the following year. In 1934, Sati Sulochana, the first Kannada talking picture to be released, was shot in Kolhapur, Maharashtra; Srinivasa Kalyanam became the first Tamil talkie actually shot in Tamil Nadu.[110][153] Once the first talkie features appeared, the conversion to full sound production happened as rapidly in India as it did in the United States. Already by 1932, the majority of feature productions were in sound; two years later, 164 of the 172 Indian feature films were talking pictures.[154] Since 1934, with the sole exception of 1952, India has been among the top three movie-producing countries in the world every single year.[155]

Aesthetic quality

In the first, 1930 edition of his global survey The Film Till Now, British cinema pundit Paul Rotha declared, "A film in which the speech and sound effects are perfectly synchronised and coincide with their visual image on the screen is absolutely contrary to the aims of cinema. It is a degenerate and misguided attempt to destroy the real use of the film and cannot be accepted as coming within the true boundaries of the cinema."[156] Such opinions were not rare among those who cared about cinema as an art form; Alfred Hitchcock, though he directed the first commercially successful talkie produced in Europe, held that "the silent pictures were the purest form of cinema" and scoffed at many early sound films as delivering little beside "photographs of people talking".[157] In Germany, Max Reinhardt, stage producer and movie director, expressed the belief that the talkies, "bringing to the screen stage plays ... tend to make this independent art a subsidiary of the theater and really make it only a substitute for the theater instead of an art in itself ... like reproductions of paintings."[158]

In the opinion of many film historians and aficionados, both at the time and subsequently, silent film had reached an aesthetic peak by the late 1920s and the early years of sound cinema delivered little that was comparable to the best of the silents.[160] For instance, despite fading into relative obscurity once its era had passed, silent cinema is represented by eleven films in Time Out's Centenary of Cinema Top One Hundred poll, held in 1995. The first year in which sound film production predominated over silent film—not only in the United States, but also in the West as a whole—was 1929; yet the years 1929 through 1933 are represented by three dialogueless pictures (Pandora's Box [1929], Zemlya [1930], City Lights [1931]) and zero talkies in the Time Out poll. (City Lights, like Sunrise, was released with a recorded score and sound effects, but is now customarily referred to by historians and industry professionals as a "silent"—spoken dialogue regarded as the crucial distinguishing factor between silent and sound dramatic cinema.) The earliest sound film to place is the French L'Atalante (1934), directed by Jean Vigo; the earliest Hollywood sound film to qualify is Bringing Up Baby (1938), directed by Howard Hawks.[161]

The first sound feature film to receive near-universal critical approbation was Der Blaue Engel (The Blue Angel); premiering on April 1, 1930, it was directed by Josef von Sternberg in both German and English versions for Berlin's UFA studio.[162] The first American talkie to be widely honored was All Quiet on the Western Front, directed by Lewis Milestone, which premiered April 21. The other internationally acclaimed sound drama of the year was Westfront 1918, directed by G. W. Pabst for Nero-Film of Berlin.[163] Historian Anton Kaes points to it as an example of "the new verisimilitude [that] rendered silent cinema's former emphasis on the hypnotic gaze and the symbolism of light and shadow, as well as its preference for allegorical characters, anachronistic."[159] Cultural historians consider the French L'Âge d'Or, directed by Luis Buñuel, which appeared late in 1930, to be of great aesthetic import; at the time, its erotic, blasphemous, anti-bourgeois content caused a scandal. Swiftly banned by Paris police chief Jean Chiappe, it was unavailable for fifty years.[164] The earliest sound movie now acknowledged by most film historians as a masterpiece is Nero-Film's M, directed by Fritz Lang, which premiered May 11, 1931.[165] As described by Roger Ebert, "Many early talkies felt they had to talk all the time, but Lang allows his camera to prowl through the streets and dives, providing a rat's-eye view."[166]

Cinematic form

"Talking film is as little needed as a singing book."[167] Such was the blunt proclamation of critic Viktor Shklovsky, one of the leaders of the Russian formalist movement, in 1927. While some regarded sound as irreconcilable with film art, others saw it as opening a new field of creative opportunity. The following year, a group of Soviet filmmakers, including Sergei Eisenstein, proclaimed that the use of image and sound in juxtaposition, the so-called contrapuntal method, would raise the cinema to "...unprecedented power and cultural height. Such a method for constructing the sound-film will not confine it to a national market, as must happen with the photographing of plays, but will give a greater possibility than ever before for the circulation throughout the world of a filmically expressed idea."[168] So far as one segment of the audience was concerned, however, the introduction of sound brought a virtual end to such circulation: Elizabeth C. Hamilton writes, "Silent films offered people who were deaf a rare opportunity to participate in a public discourse, cinema, on equal terms with hearing people. The emergence of sound film effectively separated deaf from hearing audience members once again."[169]

On March 12, 1929, the first feature-length talking picture made in Germany had its premiere. The inaugural Tobis Filmkunst production, it was not a drama, but a documentary sponsored by a shipping line: Melodie der Welt (Melody of the World), directed by Walter Ruttmann.[171] This was also perhaps the first feature film anywhere to significantly explore the artistic possibilities of joining the motion picture with recorded sound. As described by scholar William Moritz, the movie is "intricate, dynamic, fast-paced ... juxtapos[ing] similar cultural habits from countries around the world, with a superb orchestral score ... and many synchronized sound effects."[172] Composer Lou Lichtveld was among a number of contemporary artists struck by the film: "Melodie der Welt became the first important sound documentary, the first in which musical and unmusical sounds were composed into a single unit and in which image and sound are controlled by one and the same impulse."[173] Melodie der Welt was a direct influence on the industrial film Philips Radio (1931), directed by Dutch avant-garde filmmaker Joris Ivens and scored by Lichtveld, who described its audiovisual aims:

To render the half-musical impressions of factory sounds in a complex audio world that moved from absolute music to the purely documentary noises of nature. In this film every intermediate stage can be found: such as the movement of the machine interpreted by the music, the noises of the machine dominating the musical background, the music itself is the documentary, and those scenes where the pure sound of the machine goes solo.[174]

Many similar experiments were pursued by Dziga Vertov in his 1931 Entuziazm and by Chaplin in Modern Times, a half-decade later.

A few innovative commercial directors immediately saw the ways in which sound could be employed as an integral part of cinematic storytelling, beyond the obvious function of recording speech. In Blackmail, Hitchcock manipulated the reproduction of a character's monologue so the word "knife" would leap out from a blurry stream of sound, reflecting the subjective impression of the protagonist, who is desperate to conceal her involvement in a fatal stabbing.[175] In his first film, the Paramount Applause (1929), Rouben Mamoulian created the illusion of acoustic depth by varying the volume of ambient sound in proportion to the distance of shots. At a certain point, Mamoulian wanted the audience to hear one character singing at the same time as another prays; according to the director, "They said we couldn't record the two things—the song and the prayer—on one mike and one channel. So I said to the sound man, 'Why not use two mikes and two channels and combine the two tracks in printing?'"[176] Such methods would eventually become standard procedure in popular filmmaking.

One of the first commercial films to take full advantage of the new opportunities provided by recorded sound was Le Million, directed by René Clair and produced by Tobis's French division. Premiering in Paris in April 1931 and New York a month later, the picture was both a critical and popular success. A musical comedy with a barebones plot, it is memorable for its formal accomplishments, in particular, its emphatically artificial treatment of sound. As described by scholar Donald Crafton,

Le Million never lets us forget that the acoustic component is as much a construction as the whitewashed sets. [It] replaced dialogue with actors singing and talking in rhyming couplets. Clair created teasing confusions between on- and off-screen sound. He also experimented with asynchronous audio tricks, as in the famous scene in which a chase after a coat is synched to the cheers of an invisible football (or rugby) crowd.[177]

These and similar techniques became part of the vocabulary of the sound comedy film, though as special effects and "color", not as the basis for the kind of comprehensive, non-naturalistic design achieved by Clair. Outside of the comedic field, the sort of bold play with sound exemplified by Melodie der Welt and Le Million would be pursued very rarely in commercial production. Hollywood, in particular, incorporated sound into a reliable system of genre-based moviemaking, in which the formal possibilities of the new medium were subordinated to the traditional goals of star affirmation and straightforward storytelling. As accurately predicted in 1928 by Frank Woods, secretary of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, "The talking pictures of the future will follow the general line of treatment heretofore developed by the silent drama.... The talking scenes will require different handling, but the general construction of the story will be much the same."[178]

See also

- Category:Film sound production for articles concerning the development of cinematic sound recording

- History of film

- List of film sound systems

- Sound stage

- The American Fotoplayer

Notes

- Wierzbicki (2009), p. 74; "Representative Kinematograph Shows" (1907).The Auxetophone and Other Compressed-Air Gramophones Archived September 18, 2010, at the Wayback Machine explains pneumatic amplification and includes several detailed photographs of Gaumont's Elgéphone, which was apparently a slightly later and more elaborate version of the Chronomégaphone.

- Robinson (1997), p. 23.

- Robertson (2001) claims that German inventor and filmmaker Oskar Messter began projecting sound motion pictures at 21 Unter den Linden in September 1896 (p. 168), but this seems to be an error. Koerber (1996) notes that after Messter acquired the Cinema Unter den Linden (located in the back room of a restaurant), it reopened under his management on September 21, 1896 (p. 53), but no source beside Robertson describes Messter as screening sound films before 1903.

- Altman (2005), p. 158; Cosandey (1996).

- Lloyd and Robinson (1986), p. 91; Barnier (2002), pp. 25, 29; Robertson (2001), p. 168. Gratioulet went by his given name, Clément-Maurice, and is referred to thus in many sources, including Robertson and Barnier. Robertson incorrectly states that the Phono-Cinéma-Théâtre was a presentation of the Gaumont Co.; in fact, it was presented under the aegis of Paul Decauville (Barnier, ibid.).

- Sound engineer Mark Ulano, in "The Movies Are Born a Child of the Phonograph" (part 2 of his essay "Moving Pictures That Talk"), describes the Phono-Cinéma-Théâtre version of synchronized sound cinema:

This system used an operator adjusted non-linkage form of primitive synchronization. The scenes to be shown were first filmed, and then the performers recorded their dialogue or songs on the Lioretograph (usually a Le Éclat concert cylinder format phonograph) trying to match tempo with the projected filmed performance. In showing the films, synchronization of sorts was achieved by adjusting the hand cranked film projector's speed to match the phonograph. the projectionist was equipped with a telephone through which he listened to the phonograph which was located in the orchestra pit.

- Crafton (1997), p. 37.

- Barnier (2002), p. 29.

- Altman (2005), p. 158. If there was a drawback to the Elgéphone, it was apparently not a lack of volume. Dan Gilmore describes its predecessor technology in his 2004 essay "What's Louder than Loud? The Auxetophone": "Was the Auxetophone loud? It was painfully loud." For a more detailed report of Auxetophone-induced discomfort, see The Auxetophone and Other Compressed-Air Gramophones Archived September 18, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- Altman (2005), pp. 158–65; Altman (1995).

- Gomery (1985), pp. 54–55.

- Lindvall (2007), pp. 118–25; Carey (1999), pp. 322–23.

- Ruhmer (1901), p. 36.

- Ruhmer (1908), p. 39.

- Crawford (1931), p. 638.

- Eyman (1997), pp. 30–31.

- Crawford (1931), p. 638.

- Sipilä, Kari (April 2004). "A Country That Innovates". Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved December 8, 2009. "Eric Tigerstedt". Film Sound Sweden. Retrieved December 8, 2009. See also A. M. Pertti Kuusela, E.M.C Tigerstedt "Suomen Edison" (Insinööritieto Oy: 1981).

- Bognár (2000), p. 197.

- Gomery (1985), pp. 55–56.

- Sponable (1947), part 2.

- Crafton (1997), pp. 51–52; Moone (2004); Łotysz (2006). Note that Crafton and Łotysz describe the demonstration as taking place at an AIEE conference. Moone, writing for the journal of the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign's Electrical and Computer Engineering Department, says the audience was "members of the Urbana chapter of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers."

- MacDonald, Laurence E. (1998). The Invisible Art of Film Music: A Comprehensive History. Lanham, MD: Ardsley House. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-880157-56-5.

- Gomery (2005), p. 30; Eyman (1997), p. 49.

- "12 mentiras de la historia que nos tragamos sin rechistar (4)". MSN (in Spanish). Archived from the original on February 7, 2019. Retrieved February 6, 2019.

- EFE (November 3, 2010). "La primera película sonora era española". El País (in Spanish). ISSN 1134-6582. Retrieved February 6, 2019.

- López, Alfred (April 15, 2016). "¿Sabías que 'El cantor de jazz' no fue realmente la primera película sonora de la historia del cine?". 20 minutos (in Spanish). Retrieved February 6, 2020.

- Crafton, Donald (1999). The Talkies: American Cinema's Transition to Sound, 1926-1931. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. p. 65. ISBN 0-520-22128-1.

- Hall, Brenda J. (July 28, 2008). "Freeman Harrison Owens (1890–1979)". Encyclopedia of Arkansas History and Culture. Retrieved December 7, 2009.

- A few sources indicate that the film was released in 1923, but the two most recent authoritative histories that discuss the film—Crafton (1997), p. 66; Hijiya (1992), p. 103—both give 1924. There are claims that De Forest recorded a synchronized musical score for director Fritz Lang's Siegfried (1924) when it arrived in the United States the year after its German debut—Geduld (1975), p. 100; Crafton (1997), pp. 66, 564—which would make it the first feature film with synchronized sound throughout. There is no consensus, however, concerning when this recording took place or if the film was ever actually presented with synch-sound. For a possible occasion for such a recording, see the August 24, 1925, New York Times review of Siegfried Archived April 5, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, following its American premiere at New York City's Century Theater the night before, which describes the score's performance by a live orchestra.

- Quoted in Lasky (1989), p. 20.

- Low (1997a), p. 203; Low (1997b), p. 183.

- Robertson (2001), p. 168.

- Crisp (1997), pp. 97–98; Crafton (1997), pp. 419–20.

- Sponable (1947), part 4.

- See Freeman Harrison Owens (1890–1979), op. cit. A number of sources erroneously state that Owens's and/or the Tri-Ergon patents were essential to the creation of the Fox-Case Movietone system.

- Bradley (1996), p. 4; Gomery (2005), p. 29. Crafton (1997) misleadingly implies that Griffith's film had not previously been exhibited commercially before its sound-enhanced premiere. He also misidentifies Ralph Graves as Richard Grace (p. 58).

- Crafton (1997), pp. 71–72.

- Historical Development of Sound Films, E.I.Sponable, Journal of the SMPTE Vol. 48 April 1947

- The eight musical shorts were Caro Nome, An Evening on the Don, La Fiesta, His Pastimes, The Kreutzer Sonata, Mischa Elman, Overture "Tannhäuser" and Vesti La Giubba.

- Crafton (1997), pp. 76–87; Gomery (2005), pp. 38–40.

- Liebman (2003), p. 398.

- Schoenherr, Steven E. (March 24, 2002). "Dynamic Range". Recording Technology History. History Department at the University of San Diego. Archived from the original on September 5, 2006. Retrieved December 11, 2009.

- Schoenherr, Steven E. (October 6, 1999). "Motion Picture Sound 1910–1929". Recording Technology History. History Department at the University of San Diego. Archived from the original on April 29, 2007. Retrieved December 11, 2009.

- History of Sound Motion Pictures by Edward W. Kellogg, Journal of the SMPTE Vol. 64 June 1955

- The Bell "Rubber Line" Recorder Archived January 17, 2013, at the Wayback Machine.

- Crafton (1997), p. 70.

- Schoenherr, Steven E. (January 9, 2000). "Sound Recording Research at Bell Labs". Recording Technology History. History Department at the University of San Diego. Archived from the original on May 22, 2007. Retrieved December 7, 2009.

- Gomery (2005), pp. 42, 50. See also Motion Picture Sound 1910–1929 Archived May 13, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, perhaps the best online source for details on these developments, though here it fails to note that Fox's original deal for the Western Electric technology involved a sublicensing arrangement.

- Crafton (1997), pp. 129–30.

- Gomery (1985), p. 60; Crafton (1997), p. 131.

- Gomery (2005), p. 51.

- Lasky (1989), pp. 21–22.

- Eyman (1997), pp. 149–50.