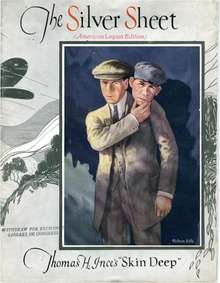

Milton Sills

Milton George Gustavus Sills (January 12, 1882 – September 15, 1930) was an American stage and film actor of the early twentieth century.

Milton G. G. Sills | |

|---|---|

Sills in 1920 | |

| Born | Milton George Gustavus Sills January 12, 1882 Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died | September 15, 1930 (aged 48) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Occupation | Actor |

| Years active | 1906–1914 (stage) 1914–1930 (film) |

| Spouse(s) | Gladys Edith Wynne ( m. 1910–1925)(his death) |

Biography

Sills was born in Chicago, Illinois into a wealthy family. He was the son of William Henry Sills, a successful mineral dealer, and Josephine Antoinette Troost Sills, an heiress from a prosperous banking family. Upon completing high school, Sills was offered a one-year scholarship to the University of Chicago, where he studied psychology and philosophy. After graduating, he was offered a position at the university as a researcher and within several years worked his way up to become a professor at the school.

In 1905, stage actor Donald Robertson visited the school to lecture on author and playwright Henrik Ibsen and suggested to Sills that he try his hand at acting. On a whim, Sills agreed and left his teaching career to embark on a stint in acting. Sills joined Robertson's stock theater company and began touring the country.

In 1908, while Sills was performing in New York City, he attracted the notice of Broadway producers such as David Belasco and Charles Frohman. That same year he made his Broadway debut in This Woman and This Man.[1] From 1908 to 1914, Sills appeared in about a dozen Broadway shows.

In 1910, Sills married English stage actress Gladys Edith Wynne, a niece of actress Edith Wynne Matthison. The union produced one child, Dorothy Sills; Gladys filed for divorce in 1925.[2] In 1926, Sills married silent film actress Doris Kenyon with whom he had a son, Kenyon Clarence Sills, born in 1927.

Motion pictures

In 1914, Sills made his film debut in the big-budget drama The Pit for the World Film Company and was signed to a contract with film producer William A. Brady. Sills made three more films for the company, including The Deep Purple opposite Clara Kimball Young.[1]

By the early 1920s, Sills had achieved matinee idol status[3] and was working for various film studios, including Metro Pictures, Famous Players-Lasky, and Pathé Exchange. In 1923 he was Colleen Moore's leading man in the very successful Flaming Youth,[4] but his biggest box office success was The Sea Hawk (1924), the top-grossing film of that year.[5] In 1926 he wrote the screenplay for Men of Steel, also starring in it along with Kenyon.[6]

Sills had begun to make the transition to sound pictures as early as 1928 with the part-talking The Barker. His final appearance was in the title role of The Sea Wolf (1930), a performance called "incisive" by the New York Times.[7]

Death and legacy

Sills died unexpectedly of a heart attack in 1930 while playing tennis with his wife at his Brentwood home in Los Angeles, California at the age of 48. He was interred at the Rosehill Cemetery and Mausoleum in Chicago, Illinois. In December 1930, Photoplay published a poem found among his personal effects.[8]

He was a founding member in 1913 of Actors' Equity.[9] On May 11, 1927, he was among the original 36 individuals in the film industry to found the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS), a professional honorary organization dedicated to the advancement of the arts and sciences of motion pictures.[10]

Sills also wrote a book, published posthumously in 1932: Values: A Philosophy of Human Needs – Six Dialogues on Subjects from Reality to Immortality, co-edited by Ernest Holmes.[11]

For his contribution to the motion picture industry, Milton Sills received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 6263 Hollywood Boulevard.[12] Sills was the favorite actor of poet Weldon Kees as a child, and Sills' Men of Steel influenced Kees' poem "1926".[13]

Filmography

- The Pit (1914) as Corthell

- The Deep Purple (1915) as William Lake

- The Arrival of Perpetua (1915) as Thaddeus Curzon

- Under Southern Skies (1915) as Burleigh Mavor

- The Rack (1915) as Tom Gordon

- Patria (1917) as Capt. Donald Parr

- The Honor System (1917) as Joseph Stanton

- Souls Adrift (1917) as Micah Steele

- Married in Name Only (1917) as Robert Worthing

- The Fringe of Society (1917) as Martin Drake

- Diamonds and Pearls (1917) as RobertVan Ellstrom

- The Other Woman (1918) as Mr. Harrington

- The Struggle Everlasting (1918) as Mind, aka Bruce

- The Reason Why (1918) as Lord Tancred

- The Mysterious Client (1918) as Harry Nelson

- The Yellow Ticket (1918) as Julian Rolfe

- The Claw (1918) as Major Anthony Kinsella

- The Savage Woman (1918) as Jean Lerier

- The Hell Cat (1918) as Sheriff Jack Webb

- Shadows (1919) as Judson Barnes

- Satan Junior (1919) as Paul Worden

- The Stronger Vow (1919) as Juan Estudillo

- The Hushed Hour (1919) as Luke Appleton

- The Woman Thou Gavest Me (1919) as Conrad

- The Fear Woman (1919) as Robert Craig

- Eyes of Youth (1919) as Louis Anthony

- What Every Woman Learns (1919) as Walter Melrose

- The Street Called Straight (1920) as Peter Devenant

- The Inferior Sex (1920) as Knox Randall

- Dangerous to Men (1920) as Sandy Verrall

- The Week-End (1920) asArthur Tavenor

- Behold My Wife! (1920) as Frank Armour

- Sweet Lavender (1920) as Horace Weather Burn

- The Furnace (1920) as Keene Mordaunt

- The Faith Healer (1921) as Michaelis

- The Little Fool (1921) as Dick

- Salvage (1921) as Fred Martin

- The Great Moment (1921) as Bayard Delaval

- At the End of the World (1921)

- Miss Lulu Bett (1921) as Neil Cornish

- A Trip to Paramountown (1922, Short)

- One Clear Call (1922) as Dr. Alan Hamilton

- The Woman Who Walked Alone (1922) as Clement Gaunt

- Borderland (1922) as James Wayne

- Burning Sands (1922) as Daniel Lane

- Skin Deep (1922) as Bud Doyle

- The Forgotten Law (1922) as Richard Jarnette

- Environment (1922) as Steve MacLaren

- The Marriage Chance (1922) as William Bradley

- The Last Hour (1923) as Steve Cline

- What a Wife Learned (1923) as Rudolph Martin

- The Isle of Lost Ships (1923) as Frank Howard

- Legally Dead (1923) as Will Campbell / George Brown

- The Spoilers (1923) as Roy Glennister

- Adam's Rib (1923) as Michael Ramsay

- Why Women Remarry (1923) as Dan Hannon

- Flaming Youth (1923) as Cary Scott

- Souls for Sale (1923) as Himself (uncredited)

- A Lady of Quality (1924) as Gerald Mertoun, Duke of Osmonde

- The Heart Bandit (1924) as John Rand

- Flowing Gold (1924) as Calvin Gray

- The Sea Hawk (1924) as Sir Oliver Tressilian

- Single Wives (1924) as Perry Jordan

- Madonna of the Streets (1924) as Reverend John Morton

- As Man Desires (1925) as Major John Craig

- I Want My Man (1925) as Gulian Eyre

- The Making of O'Malley (1925) as O'Malley

- The Knockout (1925) as Sandy Donlin

- A Lover's Oath (1925) -- editor

- The Unguarded Hour (1925) as Andrea

- Puppets (1926) as Nicki

- Men of Steel (1926) as Jan Bokak

- Paradise (1926) as Tony

- The Silent Lover (1926) as Count Pierre Tornal

- The Sea Tiger (1927) as Justin Ramos

- Framed (1927) as Etienne Hilaire

- Hard-Boiled Haggerty (1927) as Hard-Boiled Haggerty

- The Valley of the Giants (1927) as Bryce Cardigan

- Burning Daylight (1928) as Elam 'Burning Daylight' Harnish

- The Hawk's Nest (1928) as The Hawk / John Finchley

- The Crash (1928) as Jim Flannagan

- The Barker (1928) as Nifty Miller

- His Captive Woman (1929) as Officer Thomas McCarthy

- Love and the Devil (1929) as Lord Dryan

- Man Trouble (1930) as Mac

- The Sea Wolf (1930) as 'Wolf' Larsen (final film role)

References

- Golden, Eve (2000). Golden Images: 41 Essays on Silent Film Stars. McFarland. p. 163. ISBN 978-0-7864-8354-9.

- "News from the Dailies – Los Angeles". Variety. October 7, 1925. p. 10 – via Internet Archive.

- Basinger, Jeanine (October 2012). Silent Stars. Knopf Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-307-82918-4.

- Ross, Sara (2000). "The Hollywood Flapper and the Culture of Media Consumption". In Desser, David; Jowett, Garth (eds.). Hollywood Goes Shopping. U of Minnesota Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-8166-3513-9.

- Dirks, Tim. "Box-Office Hits By Decade and Year". filmsite. Archived from the original on 2015-11-21. Retrieved 2016-02-07.

- "Men of Steel". Catalog of Feature Films. American Film Institute.

- "Milton Sills's Last Film". The New York Times. October 6, 1930. Retrieved 2016-02-07.

- "Milton Sills' Goodbye". Photoplay. December 1930. p. 96 – via Internet Archive.

- Bloom, Ken (2013). Routledge Guide to Broadway. Taylor & Francis. p. 21. ISBN 978-1-135-87116-1.

- Pawlak, Debra Ann (2012). Bringing Up Oscar: The Story of the Men and Women Who Founded the Academy. Pegasus Books. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-60598-216-8.

- Soister, John T. (2012). American Silent Horror, Science Fiction and Fantasy Feature Films, 1913–1929. McFarland. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-7864-8790-5.

- "Milton Sills". Hollywood Walk of Fame. Hollywood Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved 2016-02-04.

- Reidel, James (2007). Vanished Act: The Life and Art of Weldon Kees. U of Nebraska Press. p. 20. ISBN 0-8032-5977-8.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Milton Sills. |

- Milton Sills on IMDb

- Milton Sills at the Internet Broadway Database

- Photographs and literature

- "The Actor's Part", article written by Sills in 1927