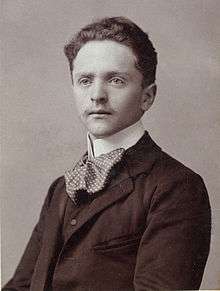

Béla Balázs

Béla Balázs (Hungarian: [ˈbeːlɒ ˈbɒlaːʒ]; 4 August 1884 in Szeged – 17 May 1949 in Budapest), born Herbert Béla Bauer, was a Hungarian film critic, aesthetician, writer and poet of Jewish heritage. He was a proponent of formalist film theory.

Career

Balázs was the son of Simon Bauer and Eugénia Léwy, adopting his nom de plume in newspaper articles written before his 1902 move to Budapest, where he studied Hungarian and German at the Eötvös Collegium.

Balázs was a moving force in the Sonntagskreis or Sunday Circle, the intellectual discussion group which he founded in the autumn of 1915 together with Lajos Fülep, Arnold Hauser, György Lukács and Károly (Karl) Mannheim. Meetings were held at his flat on Sunday afternoons; already in December 1915 Balázs wrote in his diary of the success of the group.[1]

He is perhaps best remembered as the librettist of Bluebeard's Castle which he originally wrote for his roommate Zoltán Kodály, who in turn introduced him to the eventual composer of the opera, Béla Bartók. This collaboration continued with the scenario for the ballet The Wooden Prince.

The collapse of the short-lived Hungarian Soviet Republic under Béla Kun in 1919 began a long period of exile in Vienna and Germany and, from 1933 until 1945, the Soviet Union.

In Vienna he became a prolific writer of film reviews. His first book on film, Der Sichtbare Mensch (The Visible Man) (1924), helped found the German "film as a language" theory, which also exerted an influence on Sergei Eisenstein and Vsevolod Pudovkin. A popular consultant, he wrote the screenplay for G. W. Pabst's film of Die Dreigroschenoper (1931), which became the object of a scandal and lawsuit by Brecht (who admitted to not reading the script) during production.

Later, he co-wrote (with Carl Mayer) and helped Leni Riefenstahl direct the film Das blaue Licht (1932).[2] Riefenstahl later removed Balázs's and Mayer's names from the credits because they were Jewish.[3] One of his best known films is Somewhere in Europe (It Happened in Europe, 1947), directed by Géza von Radványi.

His last years were marked by petty vexations at home and ever increasing recognition in the German-speaking world. In 1949, he received the most distinguished prize in Hungary, the Kossuth Prize. Also in 1949, he finished Theory of the Film, published posthumously in English (London: Denis Dobson, 1952). In 1958, the Béla Balázs Prize was founded and named for him as an award to recognize achievements in cinematography.

Selected filmography

- Modern Marriages (1924)

- Madame Wants No Children (1926)

- One Plus One Equals Three (1927)

- The Girl with the Five Zeros (1927)

- Grand Hotel (1927)

- Doña Juana (1927)

- Sunday of Life (1931)

See also

- Ballets by Béla Balázs

- Film semiotics

References

- Mary Gluck (1985) Georg Lukács and His Generation, 1900–1918. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674348664. pp. 14–16

- 1931 „the blue light“. walter-riml.at

- Hanno Loewy: "Balazs' and Leni Riefenstahl's The blue Light. A martyr's story" Archived 30 April 2004 at the Wayback Machine. Uni-konstanz.de. Retrieved on 24 May 2015.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Béla Balázs. |

- Petri Liukkonen. "Béla Balázs". Books and Writers

- Works by Béla Balázs at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Béla Balázs at Internet Archive

- Works by Béla Balázs at Open Library

- Béla Balázs on IMDb

- Article on the relationship between Riefenstahl and Balazs

- Béla Balázs on Jewish.hu's list of famous Hungarian Jews