Pansori

Pansori (Korean: 판소리) is a Korean genre of musical storytelling performed by a singer and a drummer.

| Pansori | |

Pansori performance at the Busan Cultural Center in Busan South Korea | |

| Korean name | |

|---|---|

| Hangul | |

| Revised Romanization | Pansori |

| McCune–Reischauer | P'ansori |

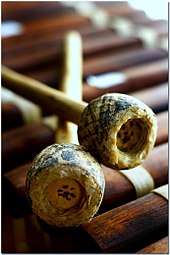

In music, Gugwangdae describes a long story that takes about three hours for short and six hours for a long time. It is one of the traditional Korean music that mixes body movements and sings to the accompaniment of buk by gosu.

Originally a form of folk entertainment for the lower classes, pansori was embraced by the Korean elite during the 19th century. While public interest in the genre declined in the mid-20th century, today, the South Korean government considers many pansori singers to be "living national treasures."[1][2] In 2003, UNESCO recognized pansori as a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity.[3]

In the late 20th century, the sorrowful "Western style" of pansori overtook the vigorous "Eastern style" of pansori, and pansori began being called the "sound of han". All surviving pansori epics end happily, but contemporary pansori focuses on the trials and tribulations of the characters, commonly without reaching the happy ending because of the contemporary popularity of excerpt performances. The history of pansori in the late 20th century, including the recent canonization of han, has led to great concern in the pansori community.[4]

Etymology

The term pansori is derived from the Korean words pan (Hangul: 판) and sori (Hangul: 소리), the latter of which means "sound." However, pan has multiple meanings, and scholars disagree on which was the intended meaning when the term was coined. One meaning is "a situation where many people are gathered." Another meaning is "a song composed of varying tones."[5]

History

Origins: 17th century

Pansori is thought to have originated in the late 17th century during the Joseon Dynasty. The earliest performers of pansori were most likely shamans and street performers, and their audiences were lower-class people.[6] It is unclear where on the Korean peninsula pansori originated, but the Honam region eventually became the site of its development.[7]

Expansion: 18th century

It is believed that pansori was embraced by the upper classes around the mid-18th century. One piece of evidence that supports this belief is that Yu Jin-han, a member of the yangban upper class, recorded the text of Chunhyangga, a famous pansori he saw performed in Honam in 1754, indicating that the elite attended pansori performances by this time.[8][9]

Golden age: 19th century

The golden age of pansori is considered to be the 19th century, when the genre's popularity increased and its musical techniques became more advanced. During the first half of the 19th century, pansori singers incorporated folk songs into the genre, while using vocal techniques and melodies intended to appeal to the upper class.[10] Purely humorous pansori also became less popular than pansori that combined humorous and tragic elements.[11]

Major developments in this period were made by pansori researcher and patron Shin Jae-hyo. He reinterpreted and compiled songs to fit the tastes of the upper class and also trained the first notable female singers, including Jin Chae-seon, who is considered to be the first female master of pansori.[12][13]

Decline: early 20th century

In the early 20th century, pansori experienced several notable changes. It was more frequently performed indoors and staged similarly to Western operas. It was recorded and sold on vinyl records for the first time. The number of female singers grew rapidly, supported by organizations of kisaeng. And the tragic tone of pansori was intensified, due to the influence of the Japanese occupation of Korea on the Korean public and performers.[14] In attempt to suppress Korean culture, the Japanese government often censored pansori that referred to the monarchy or to Korean nationalism.[15]

Preservation: late 20th century

In addition to Japanese censorship, the rise of cinema and changgeuk, and the turmoil of the Korean War all contributed to pansori's decreasing popularity by the mid-20th century.[10][15] To help preserve the tradition of pansori, the South Korean government declared it an Intangible Cultural Property in 1964. Additionally, performers of pansori began to be officially recognized as "living national treasures." This contributed to a resurgence of interest in the genre beginning in the late 1960s.[16]

Resurgence: 21st century

UNESCO proclaimed the pansori tradition a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity on November 7, 2003.[3]

The numbers of pansori performers has increased substantially in the 21st century, though the genre has struggled to find wide public appeal, and pansori audiences are composed mostly of older people, scholars or students of traditional music, and the elite.[16][17][1] However, pansori fusion music, a trend that began in the 1990s, has continued in the 21st century, with musicians creating combinations including pansori-reggae,[18][19] pansori-classical music,[20] and pansori-rap.[21]

Pansori repertoire

During the 18th century, 12 song cycles, or madang (Hangul: 마당), were established as the repertoire of pansori stories.[10][7] Those stories were compiled in Song Man-jae's Gwanuhi (Hangul: 관우희) and Jeong No-sik's Joseon Changgeuksa (Hangul: 조선창극사).[5]

Of the 12 original madang, only five are currently performed. They are as follows.[10]

Contemporary performances of the madang differ greatly from the originals. Rather than performing an entire madang, which can take up to 10 hours, musicians may only perform certain sections, highlighting the most popular parts of a madang.[10]

Musical style

There are five elements for the musical style of pansori: jo (조; 調); jangdan (장단; 長短); buchimsae (붙임새); je (제; 制); and vocal production.[22]

Jo

Jo (조; 調; also spelled cho) refers mostly to the melodic framework of a performance.[10] In terms of music in Western culture, it comparable to the mode and key, though jo also includes the vocal timbre and emotions expressed through singing. Types of jos include: chucheonmok (추천목; 鞦韆-); Gyemyeonjo (계면조; 界面調; also called seoreumjo 서름조, aewonseong 애원성); seokhwaje (석화제); and seolleongje (설렁제).[22]

Jangdan

Jangdan (장단; 長短) is the rhythmic structure used.[22] Jangdan is used to show emotional states[10] corresponding to the narration of the singer.[22] Jangdan is also used with the appearances of certain characters.[10] Some types include: jinyang (진양); jungjungmori (중중모리); jajinmori (자진모리); and hwimori (휘모리)[22]

Buchimsae

Buchimse (붙임새) refers to the method in which words in pansori are combined with the melodies. The meaning refers more specifically to combinations of words with irregular rhythms. The word is a combination of two Korean words, buchida (붙이다 "to combine") and sae (새 "appearance, form"). The two types of buchimsae are: daemadi daejangdan (대마디 대장단) and eotbuchim (엇붙임).[22]

Je

Je (제; 制) refers to a school of pansori.[22]

Gallery

A painting depicting a pansori performance, 19th century.

A painting depicting a pansori performance, 19th century.

- Pansori performance at the Busan Cultural Center in Busan, 2006.

.jpg) Pansori performance at the Changdeokgung Palace in Seoul, 2013.

Pansori performance at the Changdeokgung Palace in Seoul, 2013.

Notable pansori singers

See also

- Korean music

- Changgeuk

- Seopyeonje

Notes

- Jang (2013), p. 3-4.

- Jang (2013), p. 126-129.

- "Pansori Epic Chant". UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage. UNESCO. 2008. Retrieved 2018-02-28.

- Pilzer 2016, p. 171.

- "판소리" [Pansori]. Encyclopedia of Korean Culture (in Korean). The Academy of Korean Studies. Retrieved 2018-02-28.

- Um (2013), p. 33-39.

- Kim (2008), p. 3-4.

- Um (2013), p. 40.

- Kim (2008), p. 5.

- Gorlinski, Virginia (2013). "P'ansori". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2018-03-01.

- Kim (2008), p. 6-7.

- "Jin Chae-seon, Joseon's First Female Pansori Singer". KBS Word Radio. 2013-02-28. Retrieved 2018-03-01.

- "신재효(申在孝)" [Shin Jae-hyo]. Encyclopedia of Korean Culture (in Korean). The Academy of Korean Studies. Retrieved 2018-03-01.

- Kim (2008), pp. 14–16.

- Um (2013), pp. 47–52.

- Kim (2008), pp. 19–26.

- Um (2013), p. 12.

- Dunbar, Jon (2018-01-31). "Kim Yul-hee blends pansori, reggae". The Korea Times. Retrieved 2018-03-01.

- Yun, Suh-young (2017-06-14). "Kim Tae-yong to direct gugak performance". The Korea Times. Retrieved 2018-03-01.

- Sohn, Ji-young (2014-06-10). "Traditional Korean music with a modern twist". The Korea Herald. Retrieved 2018-03-01.

- Choi, Mun-hee (2018-02-06). "Fantastic Concert in Ancient Cave in Jeju". Business Korea. Retrieved 2018-03-01.

- "Musical structure and expression of Pansori" (PDF). National Gugak Center. Retrieved January 14, 2014.

References

- Jang, Yeonok (2013). Korean P'ansori Singing Tradition: Development, Authenticity, and Performance History. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0810884623.

- Kim, Kee Hyung (2008). "History of Pansori". In Yi, Yong-shik (ed.). Pansori. The National Center for Korean Traditional Performing Arts. ISBN 9788985952101.

- Um, Haekyung (2013). Korean Musical Drama: P'ansori and the Making of Tradition in Modernity. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 0754662764.

- Pilzer, Joshua D. (2016), "Musics of East Asia II: Korea", Excursions in World Music, Seventh Edition, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 978-1-317-21375-8