Tri-Ergon

The Tri-Ergon sound-on-film system was developed from around 1919 by three German inventors, Josef Engl (1893–1942), Joseph Massolle (1889–1957), and Hans Vogt (1890–1979).

The system used a photoelectric recording method and a non-standard film size (42mm) which incorporated the sound track with stock 35mm film. With a Swiss backer, the inventors formed Tri-Ergon AG in Zurich, and tried to interest the market with their invention.

Ufa acquired the German sound film rights for the Tri-Ergon process in 1925, but dropped the system when the public showing of their first sound film suffered technical failures.

The Tri-Ergon system appeared at a time when a number of other sound film processes were arriving on the market, and the company soon merged with a number of competitors to form the Tobis syndicate in 1928, joined by the Klangfilm AG syndicate in 1929 and renamed as Tobis-Klangfilm by 1930. While Tri-Ergon became the dominant sound film process in Germany and much of Europe through its use by Tobis-Klangfilm, American film companies were still squabbling over their respective patents. For a time Tri-Ergon successfully blocked all American attempts to show their sound films in Germany and other European countries, until a loose cartel was formed under an agreement in Paris in 1930.

However, William Fox of the Fox Film Corporation acquired the US rights for the Tri-Ergon system and, backed by Tri-Ergon AG, began a patent infringement battle in the courts in 1929 against much of the American film industry. The dispute wasn't settled until 1935, when Fox lost his final appeal in the US Supreme Court. A new Paris accord was signed in March 1936, which held until the start of the Second World War. The Tri-Ergon system continued in use in Germany and the continent during the war.

There were a number of companies which used the Tri-Ergon name:

- Tri-Ergon AG (Zurich, Switzerland), acquired the rights to the original 1919 patents from the inventors in 1923

- Tri-Ergon-Musik AG (St. Gallen, Switzerland), founded c1926, held the patents for the rest of the world outside Germany

- Tri-Ergon-Musik AG (Berlin), which made phonograph records and owned the patents for Germany, formed in 1927: a subsidiary or branch of the St. Gallen company

- Tri-Ergon-Photo-Electro-Records (Berlin), a record label subsidiary of Tri-Ergon-Musik AG (Berlin)

Etymology

The name Tri-Ergon means "the work of three", and is derived from Greek: τρία, romanized: tria, meaning three, and ἔργον, érgon, meaning 'deed, action, work, labour, or task'; cognate with Old English: weorc (English work).[1][2] The erg also derives from the same word ἔργον.

Design

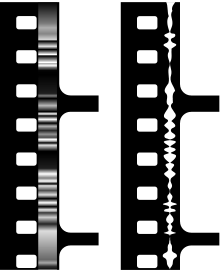

The Tri-Ergon process involved recording sound onto film using the "variable density" method, used by Movietone and Lee De Forest's Phonofilm, rather than the "variable area" method later used by RCA Photophone.[3]

Tri-Ergon used a special form of microphone without mechanical moving parts (Cathodophone) for sound pickup and a special electric discharge tube for variable density film recording. For reproduction of sound, the system used an electrostatic loudspeaker.

Two specific patents in the Tri-Ergon system would later cause controversy. The Tri-Ergon film used an extra 7mm sound strip attached to the edge of a standard 35mm film, resulting in a new film 42mm wide. This was achieved by a "double-printing" method by which the film and sound tracks were recorded and developed separately, then printed together onto a common positive.[4] This required special adjustments on the standard projectors, which was not well received by the industry.[5] The other patent was a "flywheel" which allowed the film to flow smoothly through sound reproducing equipment.[5]

An original Tri-Ergon sound movie projector (dated to 1923) is in the collection of the Deutsches Museum in München, Germany.

History

Beginnings

Massolle, Engl and Vogt secured patents from 1919 in Germany, and applied for a US patent on 20 March 1922.[9]

The first public showing of Tri-Ergon sound films took place in the Alhambra (Kino) at 68 Kurfürstendamm, Berlin on 17 September 1922. The inventors sold their patent to Swiss financial backers (St. Gallen) who formed Tri-Ergon AG in Zürich, Switzerland to continue developing their process.[10]

In 1924 Universum-Film AG (Ufa) produced three hours' worth of vaudeville shorts with sound, similar to those produced by Warner Brothers, who used a sound-on-disc system.[5] Tri-Ergon AG licensed the recording film rights to Ufa in January 1925 and Masolle briefly became technical director of Ufa's first sound-film division.[12][5]

However, the non-standard film format was not popular: even a well-publicized tour of Germany in 1925 failed to generate much interest.[5]

Ufa's first sound film, the 20-minute short Das Mädchen mit den Schwefelhölzern (1925) ('The Match Girl') was directed by Guido Bagier. Bagier (who worked at Ufa between 1922 and 1927 as producer and musical advisor)[13] also wrote the music for the film; the screenplay was by Hans Kyser. It premièred at the Mozartsaal[14] in December 1925, but was a total flop in terms of technical sound quality.[15] According to Bagier, the fiasco was due to technical problems with the playback equipment.[13][16]

The Parufmet agreement

In the meantime, Ufa, having ducked the whole issue of sound films, had still fallen into severe financial difficulties with productions of vastly expensive silent films accompanied by a live symphony orchestra playing a specially-composed score, such as F. W. Murnau's Der Letzte Mann (1924), with Emil Jannings and Faust (1926 film); and both parts of Fritz Lang's Die Nibelungen, with a score by Gottfried Huppertz.

Paramount Pictures and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer stepped into the financial breach with the highly restrictive Parufamet agreement of December 1925, whereby the American firms took control (and revenue) of all Ufa's first-run theatres to show American films.[17] Only one significant German film was shown in Ufa first-run cinemas in Berlin during this whole time the agreement was in effect: Joe May's silent The Farmer from Texas. The film received no publicity build-up and was dropped after only one week at the Ufa-Palast am Zoo.[17] Almost no German films were shown in US cinemas: and Ufa made no new films in Germany at all while the Parufamet contract was in force.[18]

Although this injection of foreign capital allowed the construction in 1926 of Ufa's enormous new Große Halle studios at Neubabelsberg (designed by Carl Stach-Urach, who had re-built the Ufa-Palast am Zoo the previous year), the Ufa management with Erich Pommer in charge of production continued to over-spend by enormous amounts. Lang's Metropolis cost over an (estimated) 5,100,000 Reichsmarks. Yet the only venue where Metropolis could be seen in the whole of Germany was at a single, small—yet equisitely decorated—cinema showing second-rate films, the Ufa-Pavillon am Nollendorfplatz.[19] The box office receipts amounted to approximately 75,000 Reichsmarks, slightly over 0.01% of the budget.

Expansion

From 1926, needing more revenue, Tri-Ergon AG sought backers in the US. On 5 July 1927 the Hungarian-American William Fox of the Fox Film Corporation personally purchased the US rights to the Tri-Ergon patents for $50,000,[5] forming the American Tri-Ergon Corporation.

Fox Film had also purchased sound-on-film patents from Freeman Harrison Owens and Theodore Case, although it seems that only the Case patents were actually used in creating the new sound-on-film system he dubbed Fox Movietone. One of the first feature films to be released in Fox Movietone was Sunrise (1927) directed by F. W. Murnau. Fox also used the system for the long-running newsreel series Fox Movietone News.

On 5 March 1927 Alfred Hugenberg's industrial Hugenberg-Gruppe took over Ufa and, as part of their initial cost-cutting measures, closed down the Tri-Ergon department. Ludwig Klitzsch, the managing director, dismissed Bagier and his team, sidestepping the problem of "the talkies" with their vast technical, financial, and legal problems.[20][10]

On 12 May 1927, Tri-Ergon-Musik-AG (Berlin), a subsidiary of Tri-Ergon-Musik-AG (St. Gallen) was formed by Joseph Masolle.[21][22] By 1931 it was a subsidiary of IG Farben, which was founded in 1925.[23] In December 1927 the Dutch firm of H. J. Küchenmeister founded a new company, International Maatschappij voor Sprekende Films NV (Sprekende Films NV) to profit from its patented 'Meisterton' system. Within a year the Dutch company would have almost total control of the Tobis and the Tri-Ergon patents.[24]

At the 1927 Baden-Baden festival of contemporary chamber-music, pioneering sound films with original scores by leading avant-garde composers were shown at special 'Film and Music' sessions. Walther Ruttmann's abstract experimental film Opus III (1924), with an original score for chamber orchestra by Hans Eisler, was shown twice: firstly as a silent film with the music performed live and synchronized using Blum's Musikchronometer, and then as a sound film (no longer extant) using the Tri-Ergon process.[25][26] The sound-film recording was supervised by Bagier, now working for Tri-Ergon-Musik A.G.[13]

Other films shown at the festivals in 1928-9 included American cartoons with music by Paul Hindemith and Ernst Toch, newsreels (Darius Milhaud), and abstract films by Hans Richter (Hindemith).[13]

By mid-1928 a number of short films had been made using the Tri-Ergon process, produced by Tobis-Industrie GmbH (TIGes) (Berlin).[27] Some of them were shown at the first public showing of sound films in Austria on 8 June 1928 at the cinema in the Urania, Vienna, a public educational institute and observatory (see also Urania-Kino (de)) They included:[28]

- Overture to The Thieving Magpie (Rossini)

- The Foreign Minister Dr. Gustav Stresemann opening the Film Exhibition in Berlin

- 'Hans in der Gaud' (Ladi Krupski, a Swiss lute singer and cabarettist) playing an old French chanson

- de:Wilhelm Scholz, president of the Prussian Academy of Poetry

- The Opel factory (probably at Rüsselsheim am Main), where the Opel Laubfrosch (Treefrog) was the first German car to be assembled on a Ford-inspired production line.

- A film about medicine by the Charité, Berlin, with an introduction by Dr. Degner[29]

- Andreas Weißgerber (later leader of the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra) playing Zigeunerweisen by Pablo de Sarasate

- A Potpourri of waltzes

- Ein Tag auf dem Bauernhof (1928) ('A day on the farm') (often misnamed "Ein Tag Film"), directed by Max Mack with Guido Bagier as unit production manager, starring Hans Albers, Georgia Lind, Willy Schaeffers, Willi Forst, Trude Lehmann, Kurt Vespermann, and Steffi von Hüne.[30][31]

- Tri-Ergon Variété

- Closing speech by the playwright and poet Ludwig Fulda

In September 1928 Walter Ruttman's full-length Stätten von deutscher Arbeit and Kultur was shown in the Vienna Urania cinema, along with Hans Moser als Wiener Dienstmann (1928), starring the Viennese comic actor Hans Moser. In the autumn of a touring exhibition of sound films was shown throughout Austria.[28] The German première of Ein Tag auf dem Bauernhof took place on 12 September 1928 at the Mozartsaal.

In July 1928 German State Radio commissioned Tri-Ergon-Musik A.G. to produce a sound film for the opening of the fifth German Radio Exhibition in Berlin. Their film Deutscher Rundfunk, with music by Edmund Meisel, showed at the exhibition in August.[32] Reviewers of the Radio Exhibition screenings were impressed by the reproduction of natural sounds, such as street noises, marching soldiers, hammering machines, steam ships and zoo animals. It was later released in a shorter version, Tönende Welle.[32]

Tobis and cartel wars

Competing American sound film companies such as RKO (formed by RCA) were becoming more organised in Germany. To protect the market from American domination the German government lobbied for a cartelization of all important German sound film patents, and on 30 August 1928 the Tobis Tonbild-Syndicate A.G. was formed to consolidate the Tri-Ergon patents and several hundred more. The four original main companies who made up the Tobis syndicate were:[33]

- Messter-Ton Film, founded in Berlin by Oskar Messter, the founder of the German film industry who had been making and showing sound-on-disc films since 1903. He merged his companies with Ufa at its founding in 1917, and owned a number of significant sound film patents.

- Tri-Ergon-Musik AG (St. Gallen) formed c1926 by Tri-Ergon AG (Zurich), which since 1923 had owned the patents registered by the original inventors in 1919. This was the parent company of Tri-Ergon-Musik AG (Berlin), formed by Masolle on 12 May 1927,[22] which made both sound films, and also phonograph records with the same photo-electric method used in the film soundtracks. The records were sold under the name Tri-Ergon-Photo-Records.

- Deutsche Tonfilm AG (Hannover), which in 1925 acquired the Petersen-Poulsen patents for German-speaking countries,[lower-alpha 2] signed a monopoly contract with Phoebus-Film (Berlin) to produce sound films.[35] Deutsche Tonfilm, Phoebus-Film and Lignose Hörfilm (see Jules Greenbaum) were all affiliated with the chemical-industrial giant IG Farben, also formed in 1925.[35][36]

- The Dutch firm of H. J. Küchenmeister, who had started making 'Meisterton' sound films in 1925 with his own Ultraphone sound-on-disc system, which used two gramophone pick-up needles to give a stereo-like sound.[35] He formed a holding company - Küchenmeisters Internationale Ultraphoon Maatschappij NV (Ultraphone) - which launched on the Amsterdam Stock Exchange in October 1928[37] It swiftly combined with German interests to form H. J. Küchenmeister-Kommanditgesellschaft (Berlin).

In this deal, Tobis acquired the option to purchase outright Tri-Ergon-Musik AG (Berlin), and made an agreement with Tri-Ergon-Musik-AG (St. Gallen) to use the Tri-Ergon sound film patents. Tobis was almost completely controlled by Küchenmeister by 1929.[38]

I Kiss Your Hand, Madame ('Ich küsse ihre Hand, Madame') was the first Tobis film with sound. Starring Harry Liedtke and Marlene Dietrich it premièred on January 16, 1929. Free of dialogue, the film's only sound segment occurs when the tenor Richard Tauber sings the title song on the soundtrack (00:32). Although Tauber appears with Liedtke and Dietrich in publicity shots for the film, he didn't appear on screen himself.[39] The film was distributed by Deutsche Lichtspiel-Syndikat (DLS),[40] a chain of 800 cinemas which had installed Küchenmeister's 'Meisterton' sound system in 1928.[41]

The main competitor of Tobis was the Klangfilm syndicate, a partnership formed in early 1929 between the electrical manufacacturers Siemens & Halske, AEG, and Polyphon-Werke A.G. (who sold Polydor records). By March 1929 Tobis merged with Klangfilm, and the resulting syndicate was renamed Tobis-Klangfilm in 1930.[33][42]

Tobis-Klangfilm made a deal with the British and French Phototone companies, and British Talking Pictures, Ltd. This made the patents of Lee de Forest available to Tobis-Klangfilm. Tobis-Klangfilm now had branches for production, distribution and equipment throughout Europe (including Tobis Portuguesa) and the United Kingdom.[33]

Meanwhile, also in 1929, Ufa and Klangfilm planned a separate contract to develop their own sound film production. Tobis (possibly because its earlier failure with Ufa in 1925) stood in direct competition with the giant Ufa as a producer of film.[39]

The premiere in March 1929 at the Baden-Baden Festival of Walther Ruttmann's Tobis film Melodie der Welt (Melody of the World), introduced the longest German sound film at the time with some 40 minutes running time.[39]

The Dutch firm of H. J. Küchenmeister planned a massive expansion of Tobis across Europe, and on 19 May 1929 issued 5,000 shares of its new company, 'Internationale Maatschappij voor Accoustiek NV' (Accoustiek NV) on the Amsterdam Stock Exchange. This was the largest Dutch flotation to date, netting 5 million Dutch guilders (approx. 8.3 million reichsmarks, $2 million, £500,000). It was over-subscribed by 3 billion guilders (about 5 billion RM), in keeping with the general stock exchange euphoria of the times.[43]

Although Tobis-Klangfilm's preparations were complete by the spring of 1929, Warner Bros. was still technically far ahead and in May 1929 tried to present The Singing Fool in Germany, a Part-Talkie with Al Jolson in a follow-up to The Jazz Singer.[44]

Tobis-Klangfilm sued both Warner Bros. and Electrical Research Products, Inc. (ERPI)—Western Electric's subsidiary for distributing its sound motion picture equipment—for patent infringement.[45] After a number of court cases, on 22 July 1929 the German appeals court upheld Tobis-Klangfilm's exclusive rights to sound-on-film recording in Germany: the company was victorious in all subsequent appeals.[46]

Tobis-Klangfilm won further injunctions in Switzerland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Holland, and Austria. Even William Fox, owner of Tri-Ergon's American rights, was prevented from presenting films in Berlin. No American films were shown at all in Berlin, and Tobis-Klang refused an offer from ERPI, Will H. Hays organised an American boycott through his company Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA).[47]

The première of Carmine Gallone's Tobis production, Das Land ohne Frauen ('The Land Without Women') - almost two hours long - on September 30, 1929, was hailed by reviews in the press as "the first feature-length German sound film".[39]

On 29 October 1929 the Wall Street Crash occurred, triggering a worldwide financial crisis.

Ufa's first major sound film, Melody of the Heart, was released in December 1929, followed in April 1930 by The Blue Angel with Dietrich and Emil Jannings, and music by Friedrich Hollaender; and in September that year The Three from the Filling Station with Lilian Harvey, Willy Fritsch and songs by the Comedian Harmonists. The success of these early sound films led the Berlin Chamber of Commerce to comment: "By now, sound film has become firmly established."[39]

1930 Paris accord

The stalemate in the ongoing patent wars between the US and European interests was broken by RCA. In the summer of 1929 General Electric (GE) acquired a part interest in AEG, one of the companies making up the original Klangfilm AG syndicate. With GE's influence, RCA and Tobis-Klangfilm signed a cooperative agreement. On 22 July 1930, at a conference in Paris, France, RCA, ERPI, and Tobis-Klangfilm formed a loose cartel to divide the world into three regions for selling sound recording and reproducing apparatus.

All pending litigation was dropped. ERPI and RCA acquired exclusive rights to sell their own recording and reproduction equipment, and distribute films in the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, India, and the Soviet Union. Royalties collected in the United Kingdom were split, 25 percent going to Tobis-Klangfilm, who also acquired similar exclusive rights in Central Europe and Scandinavia.[48]

Patent battles in the US

In 1930 Tri-Ergon AG's 1922 patent application was still pending in the United States. William Fox (who had bought the US Tri-Ergon rights in 1926) had lost control of his own company, Fox Studios, to ERPI. Backed by Tri-Ergon AG in Switzerland, he intensified the attempt to get the patent granted. In September 1931 the efforts of American Tri-Ergon Corporation's patent lawyers paid off, and he was finally assigned the US patent for the Tri-Ergon rights in the United States. The assignor was Tri-Ergon AG, who had originally applied for the US patent back in 1922.[9] The Tri-Ergon patents named particular technical features that claimed to precede all other sound-on-film patents, such as the flywheel on the sound drum.

Fox then separately sued (as test cases) Altoona Publix Theatres Inc., which leased and operated the projection equipment from RCA;[9] and Paramount for infringement of the "double printing" method. He then sued RCA and ERPI - and all the US film companies which used the Tri-Ergon design - for infringement, specifically the flywheel on the sound drum. During a series of legal tussles Fox at first won his lawsuit on appeal and then lost it after an unusual reversal of decision by the US Supreme Court in October 1934 not to review the case. The Supreme Court surprisingly relented, heard the appeal and finally ruled in March 1935 that neither system was 'new', and that there were prior inventions.[49] An appeal by Alttona Publix was rejected on 1 April 1935.[50]

Although this brought a swift end to the sound film wars between various competing US and European (Dutch, German, and Swiss) interests, it also meant that the original Tri-Ergon system was never formally adopted in the United States. As a result, William Fox's own American Tri-Ergon Corporation failed to collect an estimated $100 million in licensing fees.[51]

Financial woes

In 1931 the effects of the Wall Street Crash eventually hit Küchenmeister's Sprekende Film NV, which owned Tobis. The Dutch firm had over-extended itself with bank loans which were not renewed, and its Ultraphone business went bankrupt.[43] The hugely complex chain of inter-linked Tobis companies fell to pieces, necessitating a complete reorganisation of the whole business. Dutch bankers and creditors began re-financing the profitable parts of the company, which emerged in 1932 as 'International Tobis NV' or Intertobis [52]

1932 Paris conference

The cartel rules began to irk foreign film companies, who had to pay ERPI a license fee (royalties) to shoot the film, and then had to pay Tobis-Klang to show the film in the areas allotted to them under the 1930 accord. Another conference was held in Paris during February 1932, but Tobis-Klangfilm demanded extra royalty fees, and American companies began withholding payments.[51]

Following the Reichstag fire, the NSDAP (Nazi Party) began to suspend civil liberties and eliminate political opposition. The Communists were excluded from the Reichstag. Adolf Hitler called on Reichstag members to vote for the Enabling Act on 24 March 1933, completing his rise to power from 1919 through the Beer Hall Putsch in 1923 to Chancellor ('Reichkanzler') of the German Reich.

During the nationalisation of the German film industry in 1935, the interests of Intertobis and Ufa were clandestinely transferred to Cautio GmbH.[52] Cautio was personally set up in 1929 by Max Winkler, its sole owner and shareholder, as a front company for the secret transfer of funds from the NSDAP regime.[53] In 1935 Winkler was named by Hitler as "Reich Plenipotentiary for the German Film Industry". He had links to Max Amann, Hitler's sergeant from 1915 to 1918, president of Eher Verlag since 1922, and president of the Reich Media Council and Reich Press Leader from c1933.[54]

The new head of Tobis-Klang-film, Dr. Hans Henkel, journeyed to New York for personal negotiations in March 1936 to effect a new agreement. After two weeks' discussion all parties signed the new 1932 Paris accord on 18 March 1936 which included payment of royalties in the local currency where the film was being shown. Most American companies had withdrawn anyway from the German market by 1936, since much of their revenues were frozen under strict currency laws under the NSDAP.[55]

Ufa continued to use the Tri-Ergon system during WW2 until the collapse of Germany in 1945.[56]

Tri-Ergon records

A subsidiary, Tri-Ergon Musik AG of Berlin, made commercial phonograph records for the German, French, Swedish and Danish markets from about 1928 to 1932. The records were advertised and sold as "Tri-Ergon Photo-Electro-Records".[57][58]

The company released records of popular jazz and dance bands, and classical music. The Hungarian dance band leader Géza Komor made numerous records under both his own name and under the pseudonym of 'Harry Jackson'; other recording artists included Bernard Etté, and Friedrich Hollaender with the New Yorkers dance orchestra (e.g. "It's a Million to One You're in Love", TE 5137).[59][60]

Classical artists included the conductor and pianist Bruno Seidler-Winkler (who later made arrangements for the Comedian Harmonists) and the Tri-Ergon-Trio consisting of the cellist Gregor Piatigorsky, the pianist Karol Szreter, and the violinist Max Rostal.[61]

Recording process

The Tri-Ergon records were made by a partial reversal of the photoelectric process used to encode the sound track in the first place.[62]

See also

- Phonofilm

- Vitaphone

- List of early Warner Bros. sound and talking features

- RCA Photophone

- Photokinema

- Fox Movietone

- Joseph Tykociński-Tykociner

- Eric Tigerstedt

- Sound film

- Sound-on-disc

- List of film formats

- German inventors and discoverers

- German inventions and discoveries

References

- Notes

- Translation of the plaque:

- In this building, the former Alhambra cinema, visitors witnessed on the 17 September 1922 the world première of the first sound film of the German inventors' Triergon company. Dr. Jo Engl, Hon. Dr. Eng. Joseph Masolle, Hon. Dr. Hans Vogt[6] established with their still used light-sound process the technical foundations of sound film. Dedicated by Friedrich Jahn 17 September 1964.[7]

- About a year after Tri-Ergon's début, Axel Petersen (1887-1971) and Arnold Poulsen (1889-1952) publicly demonstrated the first sound film recorded indoors on October 12, 1923. Their enterprise, Electrical Fono Film Company, Ltd., had been founded in 1918. In 1946 the name was changed to PhonFilm Industry AB, with Ortofon as an offshoot. Ortofon started making industrial cutting heads for microgroove records and still (2019) manufactures turntable cartridges and styli.[34]

- Citations

- "ἔργον". Wiktionary. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- "Tri-Ergon" (in Swedish). FilmSoundSweden. Accessed 3 September 2017. With many photos. NB Swedish translates relatively well into English with a machine translator.

- There are analogies to be found with 'variable density' and the 'variable area' recording by considering sound broadcasting using FM and AM: or the difference between editing a bar code and a sound file.

- Gomery 1976, p. 58n.

- Gomery 1976, p. 53.

- The abbreviations are Ehren halber and honoris causa.

- In the 60s and early 70s the old Alhambra building housed one of Jahn's Wienerwald fast food restaurants.

- "Tonfilm". Gedenktafeln in Berlin. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

- American Tri-Ergon Corp v. Altoona Publix Theaters (1933) Casetext. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- Kreimeier 1999, p. 178.

- Kreimeier 1999, p. 22-25.

- The giant film conglomerate Ufa was secretly formed in 1917 by the German State as part of its propaganda effort.[11]

- Ford 2011, p. 217.

- The Mozartsaal was a cinema converted from a former concert hall, located upstairs in the Neues Schauspielhaus, 5 Nollendorfplatz, Berlin.

- Kreimeier 1999, pp. 102, 178.

- Kreimeier 1999, p. 102.

- Horak 1993, p. 55.

- Horak 1993, pp. 56-7.

- Bar-Sagi, Aitam (24 October 2013). "'Metropolis' around the World: The First Season: 1926/7". The Film Music Museum. Retrieved 3 January 2017..

- Ford 2011, p. 216.

- Bock, Mosel & Spazier 2003, p. 21.

- Ford 2011, p. 218.

- Southard 2000, pp. 99-102.

- Dibbets 2003, p. 28.

- Ruttman would go on to direct Berlin: Symphony of a Great City with Meisel's avant-garde music.

- Ruttmann's Lichtspiel Opus I was accompanied by a specially-written score by Max Butting. (Bendazzi 2015, pp. 56–57).

- "Tobis-Industrie GmbH (Tiges) (Berlin)" (in German). Filmportal. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- Wallnöfer & Petrasch 2007, p. 165.

- Medizinischer Film der Charité Berlin mit Begleitvortrag von Dr. Degner (in German). Filmportal. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- Ein Tag Film. Filmportal.de (in German). Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- Video with a sound clip from the film: "Als die Bilder sprechen lernten" (in German). Tri-Ergon. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- Ford 2011, p. 219.

- Gomery 1976, p. 54.

- "1923: Ortofon behind breakthrough in sound films". 100Yos: Denmark - The Origin of Fairytales and Loudspeakers. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- Kreimeier 1999, p. 179.

- Southard 2000, p. 102.

- Dibbets 2003, p. 27.

- Southard 2000, p. 101.

- The Emergence of German Sound Film. Filmportal.de. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- "Deutsche Lichtspiel-Syndikat (DLS) (de)". IMDb. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- Dibbets 2003, p. 29.

- Ford 2011, p. 261.

- Dibbets 2003, p. 30.

- From the start of 1930, beginning with The Jazz Singer, Warner Bros. only produced optical soundtracks, having had ditched their Vitaphone sound-on-disc system.

- Warner Bros. was itself in dispute with ERPI over royalty payments.

- Gomery 1976, pp. 53, 54.

- Gomery 1976, pp. 55-56.

- Gomery 1976, p. 57.

- Gomery 1976, p. 58-60.

- "Altoona Publix Theatres, Inc. v. American Tri-Ergon Corp." 294 U.S. 734, (U.S. 1935) Decided 1 April 1935. Ravel. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- Gomery 1976, p. 60.

- Dibbets 2003, p. 32.

- Hale 2015, p. 127.

- Whetton 2005, p. 214.

- Gomery 1976, pp. 60-61.

- Kreimeier 1996, p. 354-6, 362-4.

- "Tri-Ergon Photo-Electro-Record (Germany) / 1929". Ted Staunton's 78 rpm Label Gallery. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- "Tri-Ergon". Discogs. Received 22 October 2017.

- It's a Million to One You're in Love (Tri-Ergon records on Youtube).

- Hollaender had conducted the choir and orchestra for the performances of a huge pageant-like spectacle, Max Reinhardt's production of The Miracle by Karl Vollmöller at London's Olympia in 1911. Source: "The Miracle". The Playgoer and Society. London: Kingshurst Publishing. 5 (28). 1912.

- King, Terry (2010). Gregor Piatigorsky: The Life and Career of the Virtuoso Cellist, p. 285.

- Herlin 1929. NB This article is stuffed full of highly detailed technical diagrams and explanations (in Swedish) about the Tri-Ergon process and how it was used to make records from a previously recorded soundtrack.

Bibliography

- Bendazzi, Giannalberto (2015). Animation: A World History: Volume I: Foundations - The Golden Age. CRC Press. ISBN 9781317520832.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bock, Hans Michael; Mosel, Wiebke Annkatrin; Spazier, Ingrun, eds. (2003). Die Tobis 1928-1945: Eine kommentierte Filmografie (in German). Edition Text + Kritik. ISBN 9783883777481.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dibbets, Karel (2003). "Tobis: Made in Holland". In Distelmeyer, Jan (ed.). Tonfilmfrieden / Tonfilmkrieg.: Die Geschichte der Tobis vom Technik-Syndikat zum Staatskonzern. (chapter available in German and Dutch). Edition Text + Kritik. ISBN 9783883777498. Retrieved 22 October 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ford, Fiona (2011). The film music of Edmund Meisel (1894–1930) (PDF) (PhD thesis). University of Nottingham. Retrieved 2 September 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gomery, Douglas (1976). "Tri-Ergon, Tobis-Klangfilm, and the Coming of Sound". Cinema Journal. University of Texas Press, on behalf of the Society for Cinema & Media Studies. 16 (1). JSTOR 1225449.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) (Restricted view, subscription needed)

- Hale, Oron James (2015). The Captive Press in the Third Reich. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400868391.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Herlin, Ernst, Dr. (1929). "Elektrisk inspelning av grammofonskivor". Radio och grammofon. ('Electrical recording of gramophone discs') (in Swedish) (14). Retrieved 3 September 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) NB Swedish goes surprisingly well into English with a machine translator.

- Horak, Jan-Christopher (March 1993). "Rin-Tin-Tin in Berlin or American Cinema in Weimar". Film History. Indiana University Press. 5 (1): 49–62. JSTOR 3815109.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kreimeier, Klaus (1999). The Ufa Story: A History of Germany's Greatest Film Company, 1918–1945. Translated by Robert and Rita Kimber. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520220690.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wallnöfer, Elsbeth; Petrasch, Wilhelm (2007). Die Wiener Urania: von den Wurzeln der Erwachsenenbildung zum lebenslangen Lernen (in German). Böhlau Verlag Wien. ISBN 9783205775621.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Southard, Frank Allan (2000) [1931]. American Industry in Europe. Volume 6 of Evolution of international business, 1800-1945. London, New York: Routledge. ISBN 9780415190138.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Whetton, Cris (2005). Hitler's Fortune. Pen and Sword. ISBN 9781783035014.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Bimbambulla Foxtrot on Tri-Ergon Photo-Electro-Records, with stills of the inventors and some of the equipment.

- Tri-Ergon at IMDB