Stamford, Lincolnshire

Stamford is a town on the River Welland in Lincolnshire, England, 92 miles (148 km) north of London on the A1. The population at the 2011 census was 19,701.[2][3][4][5] The town has 17th and 18th-century stone buildings, older timber-framed buildings and five medieval parish churches.[6] Stamford is a frequent filming location. In 2013 it was rated the best place to live in a survey by The Sunday Times.[7]

| Stamford | |

|---|---|

St Mary's Hill, Stamford | |

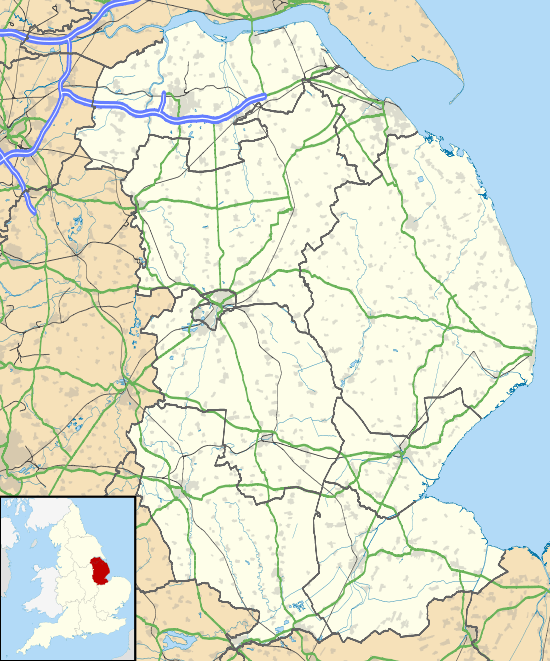

Stamford Location within Lincolnshire | |

| Population | 19,701 |

| OS grid reference | TF0207 |

| • London | 92 mi (148 km) S |

| Civil parish |

|

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | STAMFORD |

| Postcode district | PE9 |

| Dialling code | 01780 |

| Police | Lincolnshire |

| Fire | Lincolnshire |

| Ambulance | East Midlands |

| UK Parliament | |

History

The Romans built Ermine Street across what is now Burghley Park and forded the river Welland to the west of Stamford, eventually reaching Lincoln; they also built a town to the north at Great Casterton on the River Gwash. In AD 61 Boudica followed the Roman legion Legio IX Hispana across the river. The Anglo-Saxons later chose Stamford as their main town, being on a more important river than the Gwash.

The place-name Stamford is first attested in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, where it appears as Steanford in 922 and Stanford in 942. It appears as Stanford in the Domesday Book of 1086. The name means "stony ford".[8]

In 972 King Edgar made Stamford a borough. The Anglo-Saxons and Danes faced each other across the river.[9] The town had grown as a Danish settlement at the lowest point that the Welland could be crossed by ford or bridge. Stamford was the only one of the Five Boroughs of the Danelaw not to become a county town. Initially a pottery centre making Stamford Ware, by the Middle Ages it had gained fame for its production of wool and the woollen cloth known as Stamford cloth or haberget – which "In Henry III's reign... was well known in Venice."[10]

Stamford was a walled town,[9] but only a small portion of the walls remains. Stamford became an inland port on the Great North Road, the latter superseding Ermine Street in importance. Notable buildings in the town include the medieval Browne's Hospital, several churches and the buildings of Stamford School, a public school founded in 1532.[9]

A Norman castle was built about 1075 and apparently demolished in 1484.[9][11][12] The site stood derelict until the late 20th century, when it was built over and now includes a bus station and a modern housing development. A small part of the curtain wall survives at the junction of Castle Dyke and Bath Row.

During the English Civil War local loyalties were split. Thomas Hatcher MP was a Parliamentarian. Royalists used Wothorpe and Burghley as defensive positions. In the summer of 1643 the Royalists forces were besieged at Burghley on 24 July after a defeat at Peterborough on 19 July. The army of Viscount Campden was heavily outnumbered and surrendered the following day.[13]

Stamford has been hosting an annual fair since the Middle Ages. It is mentioned in Shakespeare's Henry IV, Part 2 (Act 3, Scene 2). The fair, held in mid-Lent, is the largest street fair in Lincolnshire and among the largest in the country. On 7 March 1190, crusaders at the fair led a pogrom; many Jews in the town were massacred.[14]

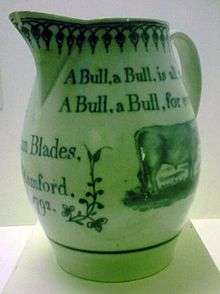

For over 600 years Stamford was the site of the Stamford Bull Run, a festival held annually on 13 November, St Brice's day, until 1839.[9][15] According to local tradition, this was started by William de Warenne, 5th Earl of Surrey, after seeing two bulls fighting in the meadow beneath his castle. Some butchers came to part the combatants and one of the bulls ran into the town. The earl mounted his horse and rode after the animal; he enjoyed the sport so much that he gave the meadow in which the fight began to the butchers of Stamford on condition that they continue to provide a bull, to be run in the town every 13 November.[9]

The East Coast Main Line was planned to go through Stamford, as an important postal town at the time, but resistance there led to routing it instead through Peterborough, whose importance and size increased at Stamford's expense.[16]

Stamford Museum occupied a Victorian building in Broad Street from 1980 to 2011. In June 2011 it was closed by Lincolnshire County Council budget cuts.[17] Some exhibits have been relocated to the Discover Stamford area at the town's library[18] and to the Town Hall.[19]

Governance

Stamford is part of the parliamentary constituency of Grantham and Stamford. The incumbent Member is Gareth Davies of the Conservative Party, who won the seat at the 2019 General Election. His predecessor, Nick Boles, had left the Conservatives in March 2019.[20][21]

In local government, Stamford since April 1974 has been in the areas of Lincolnshire County (upper tier) and South Kesteven District Council (lower tier). It formerly belonged to Kesteven County Council.

Stamford's town council[22] has arms: Per pale dexter side Gules three Lions passant guardant in pale Or and the sinister side chequy Or and Azure.[23] The three lions are the English royal arms, granted to the town by Edward IV for its part in the "Lincolnshire Uprising".[24] The blue and gold chequers are the arms of the De Warenne family, which held the Manor in the 13th century.

Geography

Stamford, as a town and civil parish in the South Kesteven district of Lincolnshire, on the River Welland, forms a south-westerly protrusion of Lincolnshire between Rutland to the north and west, Peterborough to the south, and Northamptonshire to the south-west. There have been mistaken claims of a quadripoint where four ceremonial counties – Rutland, Lincolnshire, Cambridgeshire and Northamptonshire – would meet at a point.[25] but the location actually has two tripoints some 66 ft (20 metres) apart.[26]

In 1991, the boundary between Lincolnshire and Rutland (then Leicestershire) in the Stamford area was redrawn.[27] It now mostly follows the A1 to the railway line. The conjoined parish of Wothorpe is in the city of Peterborough. Barnack Road is the Lincolnshire/Peterborough boundary where it borders St Martin's Without.

The river downstream of the town bridge and some of the meadows fall within the drainage area of the Welland and Deepings Internal Drainage Board.[28]

Geology

Much of Stamford is built on Middle Jurassic Lincolnshire limestone, with mudstones and sandstones.[29]

The area is known for its limestone and slate quarries. Collyweston stone slate, a cream-coloured stone, is found on the roofs of many Stamford stone buildings. Stamford Stone in Barnack has two quarries at Marholm and Holywell.[30] Clipsham Stone has two quarries in Clipsham.

Palaeontology

In 1968, a specimen of the sauropod dinosaur Cetiosaurus oxoniensis was found in the Williamson Cliffe Quarry, close to Great Casterton in adjacent Rutland. Some 15 metres (49 ft) long, it is about 170 million years old, from the Aalenian or Bajocian era of the Jurassic period,[31] It is one of the most complete dinosaur skeletons found in the UK. It was installed in 1975 in the New Walk Museum, Leicester.

Economy

Tourism plays an important part in Stamford's economy, as do professional law and accountancy firms. Health, education and other public-service employers also play a role, notably the hospital, a large medical general practice, schools (including independent schools) and the further education college. Hospitality is provided by a several hotels, licensed premises, restaurants, tea rooms and cafés.

The licensed premises reflect the history of the town. The George Hotel, Lord Burghley, William Cecil, Danish Invader and Jolly Brewer are among nearly 30 premises serving real ale.[32] Surrounding villages and Rutland Water provide other venues and employment opportunities, as do several annual events at Burghley House.

Retail

The town has a significant retail and service sector. The town centre has many independent boutique stores and draws shoppers from a wide area. Several streets are traffic free. The outlets include among others gift shops, eateries, men's and women's outfitters, shoe shops, florists, hairdressers, beauty therapists, and acupuncture and health-care services. Harrison Dunn, Dawson of Stamford, the George Hotel, The Crown, Arts Centre are some of the other popular places. Stamford has a number of hotels, coffee shops and restaurants. There is a branch in the town of the national jeweller F. Hinds which can trace its history back to the clockmaker Joseph Hinds, who worked in Stamford in the first half of the 19th century.[33] In the summer months Stamford Meadows attract visitors.

National supermarkets Waitrose, Marks & Spencer, Tesco, Sainsbury's and Morrisons are represented. There are two retail parks a little way from the centre. One has Homebase DIY, Curry's electrical, Carpetright floor covering and McDonald's fast-food, the other Sainsbury's, Argos, Lidl, and Halfords car spares and bicycle shop. The town has three builders' merchants and several other specialist trade outlets and skilled trades such as roofers, builders, tilers etc. There are two car showrooms and a number of car-related businesses. Local services include convenience stores, post offices, newsagents and take-aways.

Engineering

South of the town is RAF Wittering, a main employer which was until 2011 the home of the Harrier. The base opened in 1916 as RFC Stamford. It closed in 1919, but reopened in 1924 under its present name.

The engineering company, largely closed since June 2018, is Cummins Generator Technologies (formerly Newage Lyon, then Newage International), a maker of electrical generators in Barnack Road.[34] C & G Concrete (now part of Breedon Aggregates)[35] is in Uffington Road.

The Pick Motor Company was founded in Stamford in about 1898. A number of smaller firms — welders, printers and so forth — are either in small collections of industrial units or more traditional premises in older mixed-use parts of the town. Blackstone & Co was a farm implement and diesel engine manufacturing company.

Stamford lies in the midst of some of England's richest farmland and close to the famous "double-cropping" land of parts of the fens. Agriculture still provides a small, but steady number of jobs in farming, agricultural machinery, distribution and ancillary services.

Publishing and broadcasting

The Stamford Mercury claimed to have been published since 1695, as "Britain's oldest newspaper", but in fact it was founded in 1710 as the Stamford Post.[36] However, it is the oldest provincial continuous newspaper title, as The Stamford Mercury has been in print since 1712.

Local radio provision was shared between Peterborough's Heart East (102.7 - Heart Peterborough closed in July 2010) and the smaller Rutland Radio (a 97.4 transmitter on Little Casterton Road) from Oakham. Other stations include BBC Radio Cambridgeshire (95.7 from Peterborough), BBC Radio Northampton (103.6 from Corby) and BBC Radio Lincolnshire (94.9). NOW Digital broadcasts from an East Casterton transmitter covering the town and Spalding, which provides the Peterborough 12D multiplex (BBC Radio Cambridgeshire and Heart East). Stamford has its own lower-power television relay transmitter, due to the town being in a valley[37][38] which takes its transmission from Waltham, not Belmont.

Local high-profile publishers are Key Publishing (aviation) and the Bourne Publishing Group (pets). Old Glory, a specialist magazine devoted to steam power and traction engines, was published in Stamford.

Landmarks

Stamford was the first conservation area[39][40] to be designated in England and Wales under the Civic Amenities Act 1967.[41] There are over 600 listed buildings in the town and surrounding area.[42]

The Industrial Revolution largely left Stamford untouched. Much of the centre was built in the 17th and 18th centuries in Jacobean or Georgian style.[9] It is marked by streets of timber-framed and stone buildings using local limestone, and by little shops tucked down back alleys. A number of the old coaching inns survive, their large doorways being a feature of the town. The main shopping area was pedestrianised in the 1980s.

Near Stamford (but in the historical Soke of Peterborough) is Burghley House, an Elizabethan mansion, built by the First Minister of Elizabeth I, Sir William Cecil, later Lord Burghley.[9] It is the ancestral seat of the Marquess of Exeter. The tomb of William Cecil is in St Martin's Church, Stamford. The parkland of the Burghley Estate adjoins the town on two sides. Another country house near Stamford, Tolethorpe Hall, hosts outdoor theatre productions by the Stamford Shakespeare Company.[43]

Tobie Norris had a bell foundry in the town in the 17th century; his name is now given to a pub in St Paul's Street.[44]

Transport

Road

Lying on the main north-south route (Ermine Street, the Great North Road and the A1) from London to York and Edinburgh, Stamford hosted several Parliaments in the Middle Ages. The George, the Bull and Swan, the Crown and the London Inn were well-known coaching inns. The town had to cope with heavy north-south traffic through its narrow roads until 1960, when a bypass was built to the west of the town.[45] The old route is now the B1081. There is only one road bridge over the Welland, excluding the A1: a local bottleneck.[46]

Until 1996 there were plans to upgrade the bypass to motorway standard, but these have been shelved. The Carpenter's Lodge roundabout south of the town has been replaced by a grade-separated junction.[47] The old A16, now the A1175 (Uffington Road) to Market Deeping, meets the northern end of the A43 (Kettering Road) in the south of the town.

On foot

Footbridges cross the Welland at the Meadows, some 200 metres upstream of the Town Bridge, and at the Albert Bridge 250 metres downstream.[48]

The Jurassic Way runs from Banbury to Stamford. The Hereward Way runs through the town from Rutland to the Peddars Way in Norfolk, along the Roman Ermine Street and then the River Nene. The Macmillan Way heads through the town, finishing at Boston. Torpel Way follows the railway line, entering Peterborough at Bretton.

Rail

The town is served by Stamford railway station, formerly known as Stamford Town to distinguish it from the now closed Stamford East station in Water Street. The station building is a fine stone structure in Mock Tudor style, influenced by nearby Burghley House and designed by Sancton Wood.[49]

The station has direct services to Leicester, Birmingham and Stansted Airport (via Cambridge) on the Birmingham to Peterborough Line.[50] CrossCountry operates most of the services as part of their Birmingham–Stansted Airport route. Trains to and from Peterborough pass through a short tunnel beneath St Martin's High Street.

Bus

The town has a bus station on part of the old castle site in St Peter's Hill.[51] The main routes are to Peterborough via Helpston or Wansford and to Oakham, Grantham, Uppingham and Bourne. There are less frequent services to Peterborough by other routes. Delaine Buses services terminate at their depot in North Street. Other active operators include CentreBus, Blands and Peterborough Council.

On Sundays and Bank Holidays from 16 May 2010, there are five journeys to Peterborough operated by Peterborough City Council, on routes via Wittering/Wansford, Duddington/Wansford, Burghley House/Barnack/Helpston and Uffington/Barnack/Helpston. There is a National Express coach service between London and Nottingham each day, including Sundays. Route maps and timetables are on Lincolnshire County Council's website.

Waterways

Commercial shipping brought cargoes along a canal from Market Deeping to warehouses in Wharf Road until the 1850s.[9] This is no longer possible because of abandonment of the canal and the shallowness of the river above Crowland. There is a lock at the sluice in Deeping St James, but it is not in use. The river was not conventionally navigable upstream of the Town Bridge.

Education

Stamford has five state primary schools – Bluecoat, St Augustine's (RC), St George's, St Gilbert's and Malcolm Sargent, and the independent Stamford Junior School, a co-educational school for children aged two to eleven.[52]

There is one state secondary school in the town: Stamford Welland Academy (formerly Stamford Queen Eleanor School). This was formed in the late 1980s from the town's two comprehensive schools – Fane and Exeter. It became an academy in 2011. In April 2013, a group of parents announced an intention to establish a Free School in the town,[53] but they failed to receive government backing. Instead, the multi-academy trust that had submitted the bid was invited to take over the running of the existing school.[54]

Stamford School and Stamford High School are long-established independent schools with approximately 1,500 pupils combined. Stamford School for boys was founded in 1532, with the High School for girls was founded in 1877. The schools have taught co-educational classes in the sixth form since 2000. Together with Stamford Junior School, they form the Stamford Endowed Schools.[55]

Most of Lincolnshire still has grammar schools. In Stamford, the place of grammar schools was long filled by a form of the Assisted Places Scheme that provided state funding to send children to one of the two independent schools in the town that were formerly direct-grant grammars.[56] The national scheme was abolished by the 1997 Labour government. The Stamford arrangements remained in place as a protracted transitional arrangement. In 2008, the council decided no new places could be funded and the arrangement ended in 2012. The rest of South Kesteven, apart from Market Deeping, has the selective system.

Other secondary pupils travel to Casterton College or further afield to The Deepings School or Bourne Grammar School.

New College Stamford offers post-16 further education: work-based, vocational and academic; and higher education courses including BA degrees in art and design awarded by the University of Lincoln and teaching-related courses awarded by Bishop Grosseteste University.[57] The college also offers a range of informal adult learning.

In 1333–1334, a group of students and tutors from Merton and Brasenose colleges, dissatisfied with conditions at their university, left Oxford to establish a rival college at Stamford. Oxford and Cambridge universities petitioned Edward III, and the King ordered the closure of the college and the return of the students to Oxford. MA students at Oxford were obliged to swear the following: "You shall also swear that you will not read lectures, or hear them read, at Stamford, as in a University study, or college general", an oath that remained in place until 1827.[58] The site and limited remains of the former Brazenose College, Stamford, where the Oxford secessionists lived and studied, now forms part of Stamford School.[59]

Churches

In the 2011 Census, less than 67 per cent of the population of Stamford identified themselves as Christian; over 25 per cent identified themselves as of "no religion".

Stamford has many current or former churches:[9]

- All Saints' Church on Red Lion Square

- Christ Church, Green Lane

- Stamford and District Community Church (ceased to meet)

- Stamford Free Church (Baptist), Kesteven Road

- St George's Church in St George's Square

- St John the Baptist

- St Leonard's Priory

- St Mary's Church on St Mary's Street

- St Mary and St Augustine (Roman Catholic), on Broad Street

- St Martin's Church on High Street, St Martin's

- St Michael the Greater, High Street (now converted as shops)

- St Paul's Church (now the chapel of Stamford School)

- Strict Baptist Chapel, North Street

- Salvation Army, East Street (now demolished; the congregation worships elsewhere)

- The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Hillside House, Tinwell Road

- Stamford Methodist Church, Barn Hill (also known as Trinity Methodist Church)

- United Reformed Church, on Star Lane

Filming location

Television shows

- Middlemarch (1994)

- My Mad Fat Diary (2013–2015)

Films

- Pride & Prejudice (2005) – used as the village of Meryton

- The Da Vinci Code (2006)

- The Golden Bowl (2000)

Notable residents

- Michael Asher (b. 1953), FRSL, award-winning author and explorer, born in Stamford, attended Stamford School from 1964 to 1971

- Torben Betts (b. 1968), playwright, born in Stamford, attended Stamford School from 1979–1986

- Harry Burton (1879–1940) Egyptologist and archaeological photographer

- Sarah Cawood (b. 1972), television presenter

- David Cecil, 6th Marquess of Exeter (1905–1981), politician, former Governor of Bermuda, and Gold Medal-winning hurdler at the 1928 Summer Olympics. He was known as Lord Burghley until 1956.

- William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley (1520–1598), Elizabethan statesman.

- Malcolm Christie (b. 1979), former professional footballer

- Tom Davis, actor and comedian

- Colin Dexter (1930–2017), author, creator of Inspector Morse

- John Drakard (c. 1775–1854), newspaper proprietor

- Rae Earl (b. 1971), author and broadcaster

- Darren Ferguson (b. 1972), manager of Peterborough United, son of Alex Ferguson

- Lady Angela Forbes (1876–1950), novelist and First World War forces sweetheart

- Tom Ford, broadcaster, presenter 5th Gear

- Thomas Goodrich (1823–1885), cricketer

- Colin Furze (b. 1979), plumber, stuntman, filmmaker, inventor and twice a Guinness World Record holder

- John George Haigh (1909–1949), "The Acid Bath Murderer", born in Stamford

- David Jackson (b. 1947), progressive rock saxophonist, flautist, and composer

- Sir Mike Jackson (b. 1944), British army general

- Robert of Ketton (с. 1110 – с. 1160), medieval theologian, first European translator of the Qu'ran

- Rob Lynch (b. 1986), singer/songwriter

- James Mayhew (b. 1964), writer and illustrator of children's books

- Francis Peck (1692–1743), antiquarian

- Nicola Roberts (b. 1985), singer, best known for being a member of Girls Aloud

- Sir Malcolm Sargent (1895–1967), conductor

- M. J. K. Smith (b. 1933), captain of the England cricket team and the last English double international (in cricket and rugby), attended Stamford School

- Sir Michael Tippett (1905–1998), composer

- Wilfrid Wood (1888–1976),[60] artist

Sport

Football teams

- Blackstones F.C.

- Stamford A.F.C.

- Stamford Belvedere F.C.

There are a number of junior teams in each age group, and also school teams.

Rugby teams

- Stamford College Old Boys R.F.C.

- Stamford College Rugby Team

- Stamford Rugby Club

Cricket teams

- Burghley Park Cricket Club[61]

- Stamford Town Cricket Club

Festivals and events

- Burghley Horse Trials, held annually in early September

- Stamford Blues Festival

- Stamford International Music Festival held in the spring[62]

- Stamford Riverside Festival, last held in 2010

- Stamford Mid Lent Fair

- Stamford Georgian Festival, held in September

See also

- Blackstone & Co

- Outline of England

- Kings Mill, Stamford

- Niagara Falls, Ontario - Part of the area was named Stamford by John Graves Simcoe in 1791.[63]

References

- Stamford Town Council.

- "All Saints – UK Census Data 2011". UK Census Data. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- "St George's – UK Census Data 2011". UK Census Data. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- "St Mary's - UK Census Data 2011". UK Census Data. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- "Stamford St John's – UK Census Data 2011". UK Census Data. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- "Stamford Conservation Area Draft Appraisal" South Kesteven Council conservation area appraisals.

- "The winners: Our four top spots". The Sunday Times. 17 March 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2013.

- Eilert Ekwall, The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place-names, p. 436.

- Samuel Lewis, ed. (1848). A Topographical Dictionary of England. pp. 175–180 'St. Albans – Stamfordham'.

- Trevelyan, G M (1944). English Social History. p. 35.

- "David Roffe's history of Stamford Castle".

- Historic England. "Stamford Castle (347832)". PastScape. Retrieved 20 August 2009.

- "Stamford and the Civil War". www.visitoruk.com. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- "The Pogroms of 1189 and 1190 – Historic UK". Historic UK. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- November Bull-Running in Stamford, Lincolnshire; Martin W. Walsh. Journal of Popular Culture

- Cecil J. Allen, Railway Building, John F Shaw & Co, undated but 1925 or soon after, p. 6.

- Stamford Museum to close" Stamford Mercury, published: 4 June 2010 Archived 12 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- "Discover Stamford's official opening ceremony". Rutland & Stamford Mercury. 4 March 2012.

- "Town Hall – Stamford Town Council". www.stamfordtowncouncil.gov.uk. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- "Official parliament listing for constituency".

- "Town Councillors".

- "CIVIC HERALDRY OF ENGLAND AND WALES-LINCOLNSHIRE". www.civicheraldry.co.uk.

- Crowther-Beynon, V. B. (1911). Mansel Sympson, E. (ed.). Memorials of Old Lincolnshire (PDF). London: George Allen and Sons. p. 176. Retrieved 24 June 2019. Alt URL

- In minutes and seconds, 52 38' 25 north and 0 29' 4 west.

- "A real quadripoint?". blanchflower.org.

- "Boundary change IDB".

- "Welland and Deepings IDB".

- Geological Survey of England and Wales: Stamford. British Geological Survey. 1957.

- "Natural Stone suppliers of Limestone & Masonry – Stamford Stone". Stamford Stone Company.

- "1968 Williamson Cliffe brick-pit, Rutland: Late/Upper Bajocian, United Kingdom". The Paleobiology Database.

- Stamford Town Pub Map (PDF) (Issue 04 ed.). UK Pub Maps Ltd. March 2011.

- "History of Hinds clockmakers".

- "Cummins generators".

- "Breedon Group - Largest Independent Construction Materials Group". www.candgconcrete.co.uk.

- "The Rutland & Stamford Mercury". Archived from the original on 20 April 2008.

- Stamford transmitter Archived 30 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Brown, Mike. "mb21 – The Transmission Gallery". tx.mb21.co.uk.

- "First Conservation Area". Stamford Civic Society. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- "The First Conservation Area". Heritage Calling. 19 September 2017. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- "Civic Amenities Act 1967". www.legislation.gov.uk. Expert Participation. Retrieved 4 July 2018.CS1 maint: others (link)

- England, Historic. "Search the List – Find listed buildings | Historic England". historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- "Tolethorpe Hall". Stamford Shakespeare Company.

- "tobienorris.com – LCN.com". www.tobienorris.com.

- "Cinema Newsreel on opening of A1 Stamford Bypass by Minister of Transport Ernest Marples".

- Sheet 234: Rutland Water:Stamford & Oakham (Map) (A2- ed.). 1:25 000. OS Explorer. Ordnance Survey. 27 November 2008. ISBN 978-0-319-46406-9.TF030069

- "Proposal for Carpenters Lodge". Highways Agency.

- Sheet 234: Rutland Water:Stamford & Oakham (Map) (A2- ed.). 1:25 000. OS Explorer. Ordnance Survey. 27 November 2008. ISBN 978-0-319-46406-9.TF028068TF033069

- Historic England. "Stamford Station (499042)". PastScape. Retrieved 20 August 2009.

- "East Midland Trains routemap". Archived from the original on 10 June 2010.

- Stamford bus station, St Peters Hill, Town Centre, Stamford, PE9 2PE TF028070

- "Stamford endowed schools".

- "Stamford Mercury". stamfordmercury.co.uk.

- "Stamford Mercury". stamfordmercury.co.uk.

- "Stamford Endowed Schools". Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- "Last stronghold of assisted pupils faces legal threat" by Julie Henry, The Daily Telegraph 23 March 2003

- "New College website, and prospectus".

- Michael Beloff, The Plateglass Universities, p. 15.

- B. L. Deed, The History of Stamford School, Cambridge University Press, (1954), 2nd edition, 1982.

- Stamford Heritage, "Stamford Arts Centre" Archived 6 June 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Stamford Heritage. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- .

- https://simfestival.com/

- Retrieved 26 September 2019.

Further reading

- South Lincolnshire Archaeology, no. 1 (Stamford: South Lincolnshire Archaeology Unit, 1977)

- Coles, Ken (February 1980). "Queen Eleanor's Cross". The Stamford Historian. Stamford research group. Archived from the original on 19 February 2014. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- Drakard, John (1822). The History of Stamford, in the County of Lincoln: Comprising Its Ancient, Progressive, and Modern State: with an Account of St. Martin's, Stamford Baron, and Great and Little Wothorpe, Northamptonshire. J. Drakard.

- Edwards, Samuel, ed. (1810). Extracts taken from Harod's history of Stamford: relating to the navigation of the River Welland from Stamford to the Sea. Stamford.

- John S. Hartley and Alan Rogers (1974), The Religious Foundations of Medieval Stamford, Stamford Survey Group, 2. Nottingham: Department of Adult Education, University of Nottingham

- Kathy Kilmurry (1980), The Pottery Industry of Stamford, Lincs., c. AD 850–1250, British Archaeological Reports, 84. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports

- C. M. Mahany (1978), Stamford: Castle and Town. South Lincolnshire Archaeology, 2. Stamford: South Lincolnshire Archaeological Unit

- Christine Mahany, Alan Burchard and Gavin Simpson (1982), Excavations in Stamford, Lincolnshire, 1963–1969, The Society for Medieval Archaeology Monograph Series, 9. London: Society for Medieval Archaeology

- Mahany, C. M.; Roffe, D. R. (1983). "Stamford: The Development of an Anglo-Scandinavian Borough". Anglo-Norman Studies. 5: 199–219.

- Page, William, ed. (1906). A History of the County of Lincoln. Victoria County History. 2. pp. 234–235 "Hospitals: Stamford".

- Page, William, ed. (1906). A History of the County of Lincoln. Victoria County History. 2. pp. 225–230 "Friaries: Stamford".

- Plowman, Aubrey (1980). "Stamford and the Plague, 1604". The Stamford Historian. Stamford research group. Archived from the original on 23 April 2013. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- Roffe, D. R. (1981). Stamford: Its Origins and Growth. Stamford: South Lincolnshire Archaeological Unit.

- Roffe, D. R.; Mahany, C. M. (1986). "Stamford and the Norman Conquest". Lincolnshire History and Archaeology. 21: 5–9.

- Roffe, D. R. (1987). "Walter Dragun's Town? Lord and Burghal Community in Thirteenth-Century Stamford". Lincolnshire History and Archaeology. 22: 43–46.

- Roffe, D. R. (1994). Stamford in the Thirteenth Century: Two Inquisitions from the Reign of Edward I. Stamford: Paul Watkins.

- Rogers, Alan, ed. (1965). The Making of Stamford. Leicester: Leicestershire University Press.

- Rogers, Alan (2001) [1983]. the Book of Stamford. Barracuda Books 1983 edn.; Spiegl Press, Stamford 2001 edn.. ISBN 0-86023-123-2.

- Thomas, Dr. D. L. (1982). "The Cecil Monopoly of Milling in Stamford 1561-1640". The Stamford Historian. Stamford research group. Archived from the original on 24 April 2013. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- Thoresby Jones, Percy (1960). The Story of the Parish Churches of Stamford. British Publishing Co.

- Till, Dr E C. "St Cuthbert's Fee in Stamford". The Stamford Historian. Stamford research group. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Stamford (Lincolnshire). |