Antimony trioxide

Antimony(III) oxide is the inorganic compound with the formula Sb2O3. It is the most important commercial compound of antimony. It is found in nature as the minerals valentinite and senarmontite.[3] Like most polymeric oxides, Sb2O3 dissolves in aqueous solutions with hydrolysis.

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Antimony(III) oxide | |

| Other names | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.013.796 |

| EC Number |

|

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID |

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| Sb2O3 | |

| Molar mass | 291.518 g/mol |

| Appearance | white solid |

| Odor | odorless |

| Density | 5.2 g/cm3, α-form 5.67 g/cm3 β-form |

| Melting point | 656 °C (1,213 °F; 929 K) |

| Boiling point | 1,425 °C (2,597 °F; 1,698 K) (sublimes) |

| 370 ± 37 µg/L between 20.8°C and 22.9°C | |

| Solubility | soluble in acid |

| -69.4·10−6 cm3/mol | |

Refractive index (nD) |

2.087, α-form 2.35, β-form |

| Structure | |

| cubic (α)<570 °C orthorhombic (β) >570 °C | |

| pyramidal | |

| zero | |

| Hazards | |

| Safety data sheet | See: data page |

| GHS pictograms |  |

| GHS Signal word | Warning[1] |

GHS hazard statements |

H351[1] |

| P281[1] | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LD50 (median dose) |

7000 mg/kg, oral (rat) |

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |

PEL (Permissible) |

TWA 0.5 mg/m3 (as Sb)[2] |

REL (Recommended) |

TWA 0.5 mg/m3 (as Sb)[2] |

| Related compounds | |

Other anions |

Antimony trisulfide |

Other cations |

Bismuth trioxide |

Related compounds |

Diantimony tetraoxide Antimony pentoxide |

| Supplementary data page | |

| Refractive index (n), Dielectric constant (εr), etc. | |

Thermodynamic data |

Phase behaviour solid–liquid–gas |

| UV, IR, NMR, MS | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Production and properties

Global production of antimony(III) oxide in 2012 was 130,000 tonnes, an increase from 112,600 tonnes in 2002. China produces the largest share followed by US/Mexico, Europe, Japan and South Africa and other countries (2%).[4]

As of 2010, antimony(III) oxide was produced at four sites in EU27. It is produced via two routes, re-volatilizing of crude antimony(III) oxide and by oxidation of antimony metal. Oxidation of antimony metal dominates in Europe. Several processes for the production of crude antimony(III) oxide or metallic antimony from virgin material. The choice of process depends on the composition of the ore and other factors. Typical steps include mining, crushing and grinding of ore, sometimes followed by froth flotation and separation of the metal using pyrometallurgical processes (smelting or roasting) or in a few cases (e.g. when the ore is rich in precious metals) by hydrometallurgical processes. These steps do not take place in the EU but closer to the mining location.

Re-volatilizing of crude antimony(III) oxide

Step 1) Crude stibnite is oxidized to crude antimony(III) oxide using furnaces operating at approximately 500 to 1,000 °C. The reaction is the following:

- 2 Sb2S3 + 9 O2 → 2 Sb2O3 + 6 SO2

Step 2) The crude antimony(III) oxide is purified by sublimation.

Oxidation of antimony metal

Antimony metal is oxidized to antimony(III) oxide in furnaces. The reaction is exothermic. Antimony(III) oxide is formed through sublimation and recovered in bag filters. The size of the formed particles is controlled by process conditions in furnace and gas flow. The reaction can be schematically described by:

- 4 Sb + 3 O2 → 2 Sb2O3

Properties

Antimony(III) oxide is an amphoteric oxide, it dissolves in aqueous sodium hydroxide solution to give the meta-antimonite NaSbO2, which can be isolated as the trihydrate. Antimony(III) oxide also dissolves in concentrated mineral acids to give the corresponding salts, which hydrolyzes upon dilution with water.[5] With nitric acid, the trioxide is oxidized to antimony(V) oxide.[6]

When heated with carbon, the oxide is reduced to antimony metal. With other reducing agents such as sodium borohydride or lithium aluminium hydride, the unstable and very toxic gas stibine is produced.[7] When heated with potassium bitartrate, a complex salt potassium antimony tartrate, KSb(OH)2•C4H2O6 is formed.[6]

Structure

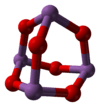

The structure of Sb2O3 depends on the temperature of the sample. Dimeric Sb4O6 is the high temperature (1560 °C) gas.[8] Sb4O6 molecules are bicyclic cages, similar to the related oxide of phosphorus(III), phosphorus trioxide.[9] The cage structure is retained in a solid that crystallizes in a cubic habit. The Sb-O distance is 197.7 pm and the O-Sb-O angle of 95.6°.[10] This form exists in nature as the mineral senarmontite.[9] Above 606 °C, the more stable form is orthorhombic, consisting of pairs of -Sb-O-Sb-O- chains that are linked by oxide bridges between the Sb centers. This form exists in nature as the mineral valentinite.[9]

| -oxide-senarmontite-xtal-2004-3D-balls.png) | -oxide-valentinite-xtal-2004-3D-balls.png) |

Uses

The annual consumption of antimony(III) oxide in the United States and Europe is approximately 10,000 and 25,000 tonnes, respectively. The main application is as flame retardant synergist in combination with halogenated materials. The combination of the halides and the antimony is key to the flame-retardant action for polymers, helping to form less flammable chars. Such flame retardants are found in electrical apparatuses, textiles, leather, and coatings.[11]

Other applications:

- Antimony(III) oxide is an opacifying agent for glasses, ceramics and enamels.

- Some specialty pigments contain antimony.

- Antimony(III) oxide is a useful catalyst in the production of polyethylene terephthalate (PET plastic) and the vulcanization of rubber.

Safety

Antimony(III) oxide has suspected carcinogenic potential for humans.[11] Its TLV is 0.5 mg/m3, as for most antimony compounds.[12]

No other human health hazards were identified for antimony(III) oxide, and no risks to human health and the environment were identified from the production and use of antimony trioxide in daily life.

References

- Record of Antimony trioxide in the GESTIS Substance Database of the Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, accessed on 23 August 2017.

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0036". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- Greenwood, N. N.; & Earnshaw, A. (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd Edn.), Oxford:Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 0-7506-3365-4.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-01-06. Retrieved 2014-01-06.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Housecroft, C. E.; Sharpe, A. G. (2008). "Chapter 15: The group 15 elements". Inorganic Chemistry (3rd ed.). Pearson. p. 481. ISBN 978-0-13-175553-6.

- Patnaik, P. (2002). Handbook of Inorganic Chemicals. McGraw-Hill. p. 56. ISBN 0-07-049439-8.

- Bellama, J. M.; MacDiarmid, A. G. (1968). "Synthesis of the Hydrides of Germanium, Phosphorus, Arsenic, and Antimony by the Solid-Phase Reaction of the Corresponding Oxide with Lithium Aluminum Hydride". Inorganic Chemistry. 7 (10): 2070–2072. doi:10.1021/ic50068a024.

- Wiberg, E.; Holleman, A. F. (2001). Inorganic Chemistry. Elsevier. ISBN 0-12-352651-5.

- Wells, A. F. (1984). Structural Inorganic Chemistry. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-855370-6.

- Svensson, C. (1975). "Refinement of the crystal structure of cubic antimony(III) oxide, Sb2O3". Acta Crystallographica B. 31 (8): 2016–2018. doi:10.1107/S0567740875006759.

- Grund, S. C.; Hanusch, K.; Breunig, H. J.; Wolf, H. U. "Antimony and Antimony Compounds". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a03_055.pub2.

- Newton, P. E.; Schroeder, R. E.; Zwick, L.; Serex, T. (2004). "Inhalation Developmental Toxicity Studies In Rats With Antimony(III) oxide (Sb2O3)". Toxicologist. 78 (1-S): 38.

Further reading

- Institut national de recherche et de sécurité (INRS), Fiche toxicologique nº 198 : Trioxyde de diantimoine, 1992.

- The Oxide Handbook, G.V. Samsonov, 1981, 2nd ed. IFI/Plenum, ISBN 0-306-65177-7