Blame

Blame is the act of censuring, holding responsible, making negative statements about an individual or group that their action or actions are socially or morally irresponsible, the opposite of praise. When someone is morally responsible for doing something wrong, their action is blameworthy. By contrast, when someone is morally responsible for doing something right, we may say that his or her action is praiseworthy. There are other senses of praise and blame that are not ethically relevant. One may praise someone's good dress sense, and blame their own sense of style for their own dress sense.

Neurology

Blaming appears to relate to include brain activity in the temporoparietal junction (TPJ).[1] The amygdala has been found[2] to contribute when we blame others, but not when we respond to their positive actions.[3]

Sociology and psychology

Humans - consciously and unconsciously - constantly make judgments about other people. The psychological criteria for judging others may be partly ingrained, negative and rigid indicating some degree of grandiosity.

Blaming provides a way of devaluing others, with the end result that the blamer feels superior, seeing others as less worthwhile making the blamer "perfect". Off-loading blame means putting the other person down by emphasizing his or her flaws.[4]

Victims of manipulation and abuse frequently feel responsible for causing negative feelings in the manipulator/abuser towards them and the resultant anxiety in themselves. This self-blame often becomes a major feature of victim status.

The victim gets trapped into a self-image of victimization. The psychological profile of victimization includes a pervasive sense of helplessness, passivity, loss of control, pessimism, negative thinking, strong feelings of guilt, shame, remorse, self-blame and depression. This way of thinking can lead to hopelessness and despair.[5]

Self-blame

Two main types of self-blame exist:

- behavioral self-blame – undeserved blame based on actions. Victims who experience behavioral self-blame feel that they should have done something differently, and therefore feel at fault.

- characterological self-blame – undeserved blame based on character. Victims who experience characterological self-blame feel there is something inherently wrong with them which has caused them to deserve to be victimized.

Behavioral self-blame is associated with feelings of guilt within the victim. While the belief that one had control during the abuse (past control) is associated with greater psychological distress, the belief that one has more control during the recovery process (present control) is associated with less distress, less withdrawal, and more cognitive reprocessing.[6]

Counseling responses found helpful in reducing self-blame include:[7]

- supportive responses

- psychoeducational responses (learning about rape trauma syndrome for example)

- responses addressing the issue of blame.

A helpful type of therapy for self-blame is cognitive restructuring or cognitive–behavioral therapy. Cognitive reprocessing is the process of taking the facts and forming a logical conclusion from them that is less influenced by shame or guilt.[8]

Victim blaming

Victim blaming is holding the victims of a crime, an accident, or any type of abusive maltreatment to be entirely or partially responsible for the incident that has occurred.

Individual blame versus system blame

In sociology individual blame is the tendency of a group or society to hold the individual responsible for his or her situation, whereas system blame is the tendency to focus on social factors that contribute to one's fate.

Blame shifting

Blaming others can lead to a "kick the dog" effect where individuals in a hierarchy blame their immediate subordinate, and this propagates down a hierarchy until the lowest rung (the "dog"). A 2009 experimental study has shown that blaming can be contagious even for uninvolved onlookers.[9]

In complex international organizations, such as national and supranational policies regulations, the blame is usually attributed to the last echelon, the implementing actors.[10]

As a propaganda technique

Labeling theory accounts for blame by postulating that when intentional actors act out to continuously blame an individual for nonexistent psychological traits and for nonexistent variables, those actors aim to induce irrational guilt at an unconscious level. Blame in this case becomes a propaganda tactic, using repetitive blaming behaviors, innuendos, and hyperbole in order to assign negative status to normative humans. When innocent people are blamed fraudulently for nonexistent psychological states and nonexistent behaviors, and there is no qualifying deviance for the blaming behaviors, the intention is to create a negative valuation of innocent humans to induce fear, by using fear mongering. For centuries, governments have used blaming in the form of demonization to influence public perceptions of various other governments, to induce feelings of nationalism in the public. Blame can objectify people, groups, and nations, typically negatively influencing the intended subjects of propaganda, compromising their objectivity. Blame is utilized as a social-control technique.

In organizations

Blame culture

The flow of blame in an organization may be a primary indicator of that organization's robustness and integrity. Blame flowing downwards, from management to staff, or laterally between professionals or partner organizations, indicates organizational failure. In a blame culture, problem-solving is replaced by blame-avoidance. Blame coming from the top generates "fear, malaise, errors, accidents, and passive-aggressive responses from the bottom", with those at the bottom feeling powerless and lacking emotional safety. Employees have expressed that organizational blame culture made them fear prosecution for errors, accidents and thus unemployment, which may make them more reluctant to report accidents, since trust is crucial to encourage accident reporting. This makes it less likely that weak indicators of safety threats get picked up, thus preventing the organization from taking adequate measures to prevent minor problems from escalating into uncontrollable situations. Several issues identified in organizations with a blame culture contradicts high reliability organizations best practices.[11][12] Organisational chaos, such as confused roles and responsibilities, is strongly associated with blame culture and workplace bullying.[12][13] Blame culture promotes a risk aversive approach, which prevent from adequately assessing risks.[12][13][14]

When an accident happens in an organization, its reaction tends to favor the individual blame logic, focusing on finding the employees who made the most prominent mistake, often those on the frontline, rather than an organization function logic, which consists in assessing the organization functioning to identify the factors which favored such an accident, despite the latter being more efficient to learn from errors and accidents.[12][15] A systematic review with nurses found similar results, with a blame culture negatively affecting the nurse's willingness to report errors, increase turnover and stress.[16] Another common strategy when several organizations work together is to blame accidents and failures on each other,[12][17] or to the last echelon such as the implementing actors.[10] Several authors suggest that this blame culture in organizations is in line and thus favored by the western legal system, where safety is a matter of individual responsibility.[12][15][18] Economic pressure is another factor associated with blame culture.[12] Some authors argue that no system is error-free, and thus focusing efforts in blaming individuals can only prevent actual understanding of the various processes that led to the fault.[18]

A study found that the perception of injustice is influenced by both the individuals assertions of their morality domain, and by their identification to the organization: the higher one identifies with the organization, the less likely one will see the organization's actions as unjust. Individuals were also increasingly suspicious when observing their peers being affected by injustices, which is a behavior in line with deontic ethics.[19]

Typology of institutions and blames

According to Mary Douglas, blame is systematically used in the micro politics of institutions, with three latent functions: explaining disasters; justifying allegiances, and stabilizing existing institutional regimes. Within a politically stable regime, blame tends to be asserted on the weak or unlucky one, but in a less stable regime, blame shifting may involve a battle between rival factions. Douglas was interested in how blame stabilizes existing power structures within institutions or social groups. She devised a two-dimensional typology of institutions, the first attribute being named "group", which is the strength of boundaries and social cohesion, the second "grid", the degree and strength of the hierarchy.[13]

| Isolate

low group, high grid |

Bureaucracy

high group, high grid |

| Market

low group, low grid |

Clan

high group, low grid |

According to Douglas, blame will fall on different entities depending on the institutional type. For markets, blame is used in power struggles between potential leaders. In bureaucracies, blame tends to flow downwards and is attributed to a failure to follow rules. In a clan, blame is asserted on outsiders or involves allegations of treachery, to suppress dissidence and strengthen the group's ties. In the 4th type, isolation, the individuals are facing the competitive pressures of the marketplace alone, in other words there is a condition of fragmentation with a loss of social cohesion, potentially leading to feelings of powerlessness and fatalism, and this type was renamed by various other authors into "donkey jobs". It is suggested that the progressive changes in managerial practices in healthcare is leading to an increase in donkey jobs.[13] The group and hierarchy strength may also explain why healthcare experts, who often devise clinical procedures on the field, may be refractory to new safety guidelines from external regulators, perceiving them as competing procedures changing cultures and imposing new lines of authority.[14]

Blaming and transparency

The requirement of accountability and transparency, assumed to be key for good governance, worsen the behaviors of blame avoidance, both at the individual and institutional levels,[20] as is observed in various domains such as politics[21] and healthcare.[22] Indeed, institutions tend to be risk-averse and blame-averse, and where the management of societal risks (the threats to society) and institutional risks (threats to the organizations managing the societal risks)[23] are not aligned, there may be organizational pressures to prioritize the management of institutional risks at the expense of societal risks.[24][25] Furthermore, "blame-avoidance behaviour at the expense of delivering core business is a well-documented organizational rationality".[24] The willingness of maintaining one's reputation may be a key factor explaining the relationship between accountability and blame avoidance.[26] This may produce a "risk colonization", where institutional risks are transferred to societal risks, as a strategy of risk management.[24][27][28] Some researchers argue that there is "no risk-free lunch" and "no blame-free risk", an analogy to the "no free lunch" adage.[29]

In healthcare

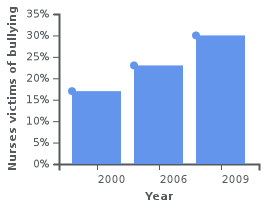

| Percentage of nurses victims of bullying in UK | |

| |

| Percentage of nurses victims of bullying in the United Kingdom from 2000 to 2009, with an increasing trend suggesting that bullying and blame culture is an organizational problem.[13] | |

Blame culture is a serious issue in safety-critical domains, where human errors can have dire consequences, for instance in hospitals and in aviation.[30][31] However, as several healthcare organizations were raising concerns,[25] studies found that increasing regulatory transparency in health care had the unintended consequence of increasing defensive practice and blame shifting.[22][32] Following rare but high-profile scandals, there are political incentives for a "self-interested blame business" promoting a presumption of "guilty until proven innocent"[22][33] A literature review found that human resource management plays an important role in health care organizations: when such organizations rely predominantly on a hierarchical, compliance-based management system, blame culture is more likely to happen, whereas when employees involvement in decision making is more elicited, a just or learning culture is more likely.[34]

Blame culture has been suggested as a major source of medical errors.[34] The World Health Organization,[35] the United States' Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality[36] and United Kingdom's National Health Service[37][38] recognize the issue of blame culture in healthcare organizations, and recommends to promote a no-blame culture, or just culture, in order to increase patients' safety, which is the prevention of errors and adverse effects to patients.[15][34][35][36][37] Other authors suggest to also provide emotional support to help healthcare professionals deal with the emotions elicited by their patients.[39] Yet others have pointed out the lack of nomination healthcare staff as directors, so that those on the field are excluded from the decision processes, and thus lack intrinsic motivation to enhance patients safety processes.[40]

In the United Kingdom, a 2018 survey of 7887 doctors found that 78% said the NHS resources are inadequate to ensure patients safety and quality of services, 95% are fearful of making a medical error and that the fear has increased in the past 5 years, 55% worry they may be unfairly blamed for errors due to systems failings and pressures, and 49% said they practice defensively.[41] A sizeable proportion of these doctors recognized the issue of bullying, harassment or undermining, 29% declaring it was sometimes an issue and 10% saying it was often an issue.[41] Dozens of UK doctors under fitness-to-practice investigations committed suicide.[18]

In 2018, an investigation into the cases of 11 deaths in Gosport War Memorial Hospital led to the discovery of an institutionally-wide inappropriate administration of powerful painkillers without medical justification, leading to the death of hundreds of patients since the 1990s. This scandal is often described as an example of the consequences blame culture, with the NHS pressuring whistleblowers, which prompted officials to address more actively this issue to avoid seeing it repeated elsewhere.[42][43]

In aviation

Aviation pioneered the shift from individual blaming to systems failure investigation, and incentivized it with the Aviation Safety Reporting System, a platform to self-report safety incidents in exchange of immunity from prosecution.[18] Since 15 November 2015, the European Occurrence Reporting Regulation (EU Reg. 376/2014) exhorts the aviation industry to implement a just culture systematically.[44]

In politics

Blame avoidance is an often observed behavior in politics, which is worsened when meeting the doctrine of transparency, assumed to be key for good governance.[21]

When politicians shift blames under polarized conditions, the public sector organizations are often the target.[45]

In other domains

For social workers, by emphasizing the professional as being autonomous and accountable, they are considered as individual workers with full agency, which occludes the structural constraints and influences of their organizations, thus promoting a blame culture on the individuals.[46] This emphasis on individual's accountability is similarly observed in healthcare.[47] In UK, blame culture prevented the adequate collaboration necessary between social workers and healthcare providers.[48]

See also

- Attribution (psychology)

- Attribution bias

- Causality

- Culpability

- Denial

- Fall guy

- Fundamental attribution error

- Moral responsibility

- Praise

- Presumption of guilt

- Psychological projection

- "Result(s)-oriented work environment" or "result(s)-only work environment" (ROWE)

- Scapegoating

References

-

Hoffman, Morris B. (2014). The Punisher's Brain: The Evolution of Judge and Jury. Cambridge Studies in Economics, Choice, and Society. Cambridge University Press. p. 68. ISBN 9781107038066. Retrieved 2014-05-22.

Our adult brains [...] have dedicated circuits devoted to the assessment of intentionality and harm, and to the calculation of blame based on those two assessments, using intent as the main driver and harm only as a tiebreaker. Part of those blaming circuits lie in a region called the temporoparietal junction, or TPJ. It is an area of the cortex roughly even with the top of the ears.

- amygdala has been found

- Ngo, Lawrence; Kelly, Meagan; Coutlee, Christopher G; Carter, R McKell; Sinnott-Armstrong, Walter; Huettel, Scott A (2015). "Two Distinct Moral Mechanisms for Ascribing and Denying Intentionality". Scientific Reports. 5: 17390. Bibcode:2015NatSR...517390N. doi:10.1038/srep17390. PMC 4669441. PMID 26634909.

Based on converging behavioral and neural evidence, we demonstrate that there is no single underlying mechanism. Instead, two distinct mechanisms together generate the asymmetry. Emotion drives ascriptions of intentionality for negative consequences, while the consideration of statistical norms leads to the denial of intentionality for positive consequences.

- Brown, N.W., Coping With Infuriating, Mean, Critical People – The Destructive Narcissistic Pattern (2006)

- Braiker, H.B., Who's Pulling Your Strings? How to Break The Cycle of Manipulation (2006)

- Frazier, P.A.; Mortensen, H.; Steward, J. (2005). "Coping Strategies as Mediators of the Relations Among Perceived Control and Distress in Sexual Assault Survivors". Journal of Counseling Psychology. 52 (3): 267–78. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.52.3.267.

- Matsushita-Arao, Y. (1997). Self-blame and depression among forcible rape survivors. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering. 57(9-B). p. 5925.

- Branscombe, N.R.; Wohl, M.J.A.; Owen, S.; Allison, J.A.; N'gbala, A. (2003). Counterfactual Thinking, Blame Assignment, and Well-Being in Rape Victims. Basic & Applied Social Psychology, 25(4), p. 265, 9p.

- Jeanna Bryner: Workplace Blame Is Contagious and Detrimental, LiveScience, 2010-01-19, citing the January 2010 issue of the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology.

- Rittberger, Berthold; Schwarzenbeck, Helena; Zangl, Bernhard (July 2017). "Where Does the Buck Stop? Explaining Public Responsibility Attributions in Complex International Institutions". JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies. 55 (4): 909–924. doi:10.1111/jcms.12524.

- McLendon, J.; Weinberg, G.M. (July 1996). "Beyond blaming: congruence in large systems development projects". IEEE Software. 13 (4): 33–42. doi:10.1109/52.526830.

- Milch, Vibeke; Laumann, Karin (February 2016). "Interorganizational complexity and organizational accident risk: A literature review". Safety Science (Review). 82: 9–17. doi:10.1016/j.ssci.2015.08.010.

- Rudge, Trudy (2016). (Re)Thinking Violence in Health Care Settings: A Critical Approach. Routledge. ISBN 9781317189190.

- Hollnagel, Erik; Braithwaite, Jeffrey (2019). Resilient Health Care. CRC Press. ISBN 9781317065166.

- Catino, Maurizio (March 2008). "A Review of Literature: Individual Blame vs. Organizational Function Logics in Accident Analysis". Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management (Review). 16 (1): 53–62. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5973.2008.00533.x. S2CID 56379831.

- Okpala, Paulchris (July 2018). "Nurses' perspectives on the impact of management approaches on the blame culture in health-care organizations". International Journal of Healthcare Management: 1–7. doi:10.1080/20479700.2018.1492771.

- Park, Brian S.; Park, Hyunwoo; Ramanujam, Rangaraj (October 2018). "Tua culpa: When an Organization Blames Its Partner for Failure in a Shared Task". Academy of Management Review (Review). 43 (4): 792–811. doi:10.5465/amr.2016.0305.

- Radhakrishna, S. (November 2015). "Culture of blame in the National Health Service; consequences and solutions". British Journal of Anaesthesia (Narrative review). 115 (5): 653–655. doi:10.1093/bja/aev152. PMID 26034020.

- Topa, Gabriela; Moriano, Juan A.; Morales, José F. (2013). "Organizational injustice: third parties' reactions to mistreatment of employee". Psicothema. 25 (2): 214–221. doi:10.7334/psicothema2012.237. PMID 23628536.

- Hinterleitner, Markus; Sager, Fritz (26 May 2016). "Anticipatory and reactive forms of blame avoidance: of foxes and lions". European Political Science Review. 9 (4): 587–606. doi:10.1017/S1755773916000126.

- Hood, Christopher (June 2007). "What happens when transparency meets blame-avoidance?". Public Management Review. 9 (2): 191–210. doi:10.1080/14719030701340275.

- McGivern, Gerry; Fischer, Michael (2010). "Medical regulation, spectacular transparency and the blame business". Journal of Health Organization and Management. 24 (6): 597–610. doi:10.1108/14777261011088683. PMID 21155435.

- Rothstein, Henry (September 2006). "The institutional origins of risk: A new agenda for risk research". Health, Risk & Society (Editorial). 8 (3): 215–221. doi:10.1080/13698570600871646. Used only for clarifying what are societal risks and institutional risks

- Rothstein, Henry; Huber, Michael; Gaskell, George (February 2006). "A theory of risk colonization: The spiralling regulatory logics of societal and institutional risk" (PDF). Economy and Society. 35 (1): 91–112. doi:10.1080/03085140500465865.

- Hood, Christopher; Rothstein, Henry (26 July 2016). "Risk Regulation Under Pressure" (PDF). Administration & Society. 33 (1): 21–53. doi:10.1177/00953990122019677. S2CID 154316481.

- Busuioc, E. Madalina; Lodge, Martin (April 2016). "The Reputational Basis of Public Accountability" (PDF). Governance. 29 (2): 247–263. doi:10.1111/gove.12161. S2CID 143427109.

- Manning, Louise; Luning, Pieternel A; Wallace, Carol A (19 September 2019). "The Evolution and Cultural Framing of Food Safety Management Systems—Where From and Where Next?". Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety (Review). 18 (6): 1770–1792. doi:10.1111/1541-4337.12484.

- Davis, Courtney; Abraham, John (August 2011). "A comparative analysis of risk management strategies in European Union and United States pharmaceutical regulation". Health, Risk & Society (Review). 13 (5): 413–431. doi:10.1080/13698575.2011.596191.

- Hood, Christopher (28 March 2014). "The Risk Game and the Blame Game". Government and Opposition. 37 (1): 15–37. doi:10.1111/1477-7053.00085.

- Phyllis Maguire: Is it time to put "no blame" in the corner?, Today's Hospitalist, December 2009

- A Roadmap to a Just Culture: Enhancing the Safety Environment, First Edition, GAIN Working Group E, September 2004

- Andersson, Thomas; Liff, Roy (25 May 2012). "Does patient-centred care mean risk aversion and risk ignoring?". International Journal of Public Sector Management. 25 (4): 260–271. doi:10.1108/09513551211244098.

- McGivern, Gerry; Fischer, Michael D. (February 2012). "Reactivity and reactions to regulatory transparency in medicine, psychotherapy and counselling" (PDF). Social Science & Medicine. 74 (3): 289–296. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.09.035. PMID 22104085.

- Khatri, Naresh; Brown, Gordon D.; Hicks, Lanis L. (October 2009). "From a blame culture to a just culture in health care". Health Care Management Review (Review). 34 (4): 312–322. doi:10.1097/HMR.0b013e3181a3b709. PMID 19858916.

- World Health Organization (26 September 2016). "Setting priorities for global patient safety - Executive summary" (PDF). who.int (International society statement). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-10-30.

- "Culture of Safety". psnet.ahrq.gov (National society statement). AHRQ. September 2019. Archived from the original on 2019-10-30.

- "From a blame culture to a learning culture". GOV.UK (National society statement). 10 March 2016. Archived from the original on 2019-07-25.

- Thomas, Will; Hujala, Anneli; Laulainen, Sanna; McMurray, Robert (2018). The Challenge of Wicked Problems in Health and Social Care. Routledge. ISBN 978-1351592529.

- Gabriel, Yiannis (4 June 2015). "Beyond Compassion: Replacing a Blame Culture With Proper Emotional Support and Management Comment on "Why and How Is Compassion Necessary to Provide Good Quality Healthcare?"". International Journal of Health Policy and Management. 4 (9): 617–619. doi:10.15171/IJHPM.2015.111. PMC 4556580. PMID 26340493.

- Stevenson, Robin (2 July 2019). "Why the NHS needs a culture shift from blame and fear to learning". The Conversation.

- Wise, Jacqui (20 September 2018). "Survey of UK doctors highlights blame culture within the NHS". BMJ. 362 (k4001): k4001. doi:10.1136/bmj.k4001. PMID 30237202.

- "NHS 'blame culture' must end, says Hunt". BBC. 21 June 2018.

- Boyle, Danny (21 June 2018). "Gosport: NHS 'blame culture' must end to prevent more hospital scandals, warns Jeremy Hunt". The Telegraph.

- European Cockpit Association. "Just Culture Needs More Than Legislation!". www.eurocockpit.be.

- Hinterleitner, Markus; Sager, Fritz (2019). "Blame, Reputation, and Organizational Responses to a Politicized Climate". The Blind Spots of Public Bureaucracy and the Politics of Non-Coordination. Springer International Publishing: 133–150. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-76672-0_7. ISBN 978-3-319-76671-3.

- Weinberg, Merlinda (25 May 2010). "The Social Construction of Social Work Ethics: Politicizing and Broadening the Lens". Journal of Progressive Human Services. 21 (1): 32–44. doi:10.1080/10428231003781774. S2CID 144799349.

- Oliver, David (8 May 2018). "David Oliver: Accountability—individual blame versus a "just culture"". BMJ (Opinion paper). 361: k1802. doi:10.1136/bmj.k1802. PMID 29739770.

- Rudgard, Olivia (3 July 2018). "Targets and 'blame culture' stop older people getting proper care". The Telegraph. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

Further reading

- Douglas, Tom. Scapegoats: Transferring Blame, London-New York, Routledge, 1995.

- Wilcox, Clifton W. Scapegoat: Targeted for Blame, Denver, Outskirts Press, 2009.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Blame. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Blame |

- Blaming

- Moral Responsibility (also on praise and blame), in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Praise and Blame, in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy