Onboarding

Onboarding, also known as organizational socialization, is management jargon first created in the 1970s that refers to the mechanism through which new employees acquire the necessary knowledge, skills, and behaviors in order to become effective organizational members and insiders.

It is the process of integrating a new employee into the organization and its culture.[2] Tactics used in this process include formal meetings, lectures, videos, printed materials, or computer-based orientations to introduce newcomers to their new jobs and organizations. Research has demonstrated that these socialization techniques lead to positive outcomes for new employees such as higher job satisfaction, better job performance, greater organizational commitment, and reduction in occupational stress and intent to quit.[3][4][5] These outcomes are particularly important to an organization looking to retain a competitive advantage in an increasingly mobile and globalized workforce. In the United States, for example, up to 25% of workers are organizational newcomers engaged in an onboarding process.[6] The term induction is used instead in regions such as Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and parts of Europe.[7] This is known in some parts of the world as training.[8]

Antecedents of success

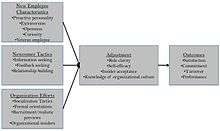

Onboarding is a multifaceted operation influenced by a number of factors pertaining to both the individual newcomer and the organization. Researchers have separated these factors into three broad categories: new employee characteristics, new employee behaviors, and organizational efforts.[9] New employee characteristics are individual differences across incoming workers, ranging from personality traits to previous work experiences. New employee behaviors refer to the specific actions carried out by newcomers as they take an active role in the socialization process. Finally, organizational efforts help facilitate the process of acclimating a new worker to an establishment through activities such as orientation or mentoring programs.

New employee characteristics

Research has shown evidence that employees with certain personality traits and experiences adjust to an organization more quickly.[10] These are a proactive personality, the "Big Five", curiosity, and greater experience levels.

"Proactive personality" refers to the tendency to take charge of situations and achieve control over one's environment. This type of personality predisposes some workers to engage in behaviors such as information seeking that accelerate the socialization process, thus helping them to adapt more efficiently and become high-functioning organizational members.[1] Empirical evidence also demonstrates that a proactive personality is related to increased levels of job satisfaction and performance.[11][12]

The Big Five personality traits—openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism—have been linked to onboarding success, as well. Specifically, new employees who are proactive or particularly open to experience are more likely to seek out information, feedback, acceptance, and relationships with co-workers. They also exhibit higher levels of adjustment and tend to frame events more positively.[4]

Curiosity also plays a substantial role in the newcomer adaptation process and is defined as the "desire to acquire knowledge" that energizes individual exploration of an organization's culture and norms.[13] Individuals with a curious disposition tend to frame challenges in a positive light and eagerly seek out information to help them make sense of their new organizational surroundings and responsibilities, leading to a smoother onboarding experience.[14]

Employee experience levels also affect the onboarding process such that more experienced members of the workforce tend to adapt to a new organization differently from, for example, a new college graduate starting their first job. This is because seasoned employees can draw from past experiences to help them adjust to their new work settings and therefore may be less affected by specific socialization efforts because they have (a) a better understanding of their own needs and requirements at work.[15] and (b) are more familiar with what is acceptable in the work context.[16][17] Additionally, veteran workers may have used their past experiences to seek out organizations in which they will be a better fit, giving them an immediate advantage in adapting to their new jobs.[18]

New employee behaviors

Certain behaviors enacted by incoming employees, such as building relationships and seeking information and feedback, can help facilitate the onboarding process. Newcomers can also quicken the speed of their adjustment by demonstrating behaviors that assist them in clarifying expectations, learning organizational values and norms, and gaining social acceptance.

Information seeking occurs when new employees ask questions of their co-workers and superiors in an effort to learn about their new job and the company's norms, expectations, procedures, and policies. Miller and Jablin (1991) report what new hires look for: referent information, understanding what is required to function on the job (role clarity); appraisal information, understanding how effectively the newcomer is able to function in relation to job role requirements (self-efficacy); and finally, relational information, information about the quality of relationships with current organizational employees (social acceptance). By actively seeking information, employees can effectively reduce uncertainties about their new jobs and organizations and make sense of their new working environments.[19] Newcomers can also passively seek information via monitoring their surroundings or by simply viewing the company website or handbook. Research has shown that information seeking by incoming employees is associated with social integration, higher levels of organizational commitment, job performance, and job satisfaction in both individualistic and collectivist cultures.[20]

Feedback seeking is similar to information seeking, but it is focused on a new employee's particular behaviors rather than on general information about the job or company. Specifically, feedback seeking refers to new employee efforts to gauge how to behave in their new organization. A new employee may ask co-workers or superiors for feedback on how well he or she is performing certain job tasks or whether certain behaviors are appropriate in the social and political context of the organization. In seeking constructive criticism about their actions, new employees learn what kinds of behaviors are expected, accepted, or frowned upon within the company or work group, and when they incorporate this feedback and adjust their behavior accordingly, they begin to blend seamlessly into the organization.[21] Instances of feedback inquiry vary across cultural contexts such that individuals high in self-assertiveness and cultures low in power distance report more feedback seeking than newcomers in cultures where self-assertiveness is low and power distance is high.[22]

Also called networking, relationship building involves an employee's efforts to develop camaraderie with co-workers and even supervisors. This can be achieved informally through simply talking to their new peers during a coffee break or through more formal means such as taking part in pre-arranged company events. Research has shown relationship building to be a key part of the onboarding process, leading to outcomes such as greater job satisfaction and better job performance,[3] as well as decreased stress.[5]

Employee and supervisor relationships

Foste & Botero (2012) research found that having positive communication and relationships between employees and supervisors is important for worker morale. The way in which a message is delivered affects how supervisors develop relationships and feelings about employees. When developing a relationship evaluating personal reputation, delivery style, and message content all played important factors in the perceptions between supervisors and employees. Yet, when supervisors were assessing work competence they primarily focused on the content of what they were discussing or the message. Creating interpersonal, professional relationships between employees and supervisors in organizations helps foster productive working relationships.

Tactics

Organizations invest a great amount of time and resources into the training and orientation of new company hires. Organizations differ in the variety of socialization activities they offer in order to integrate productive new workers. Possible activities include socialization tactics, formal orientation programs, recruitment strategies, and mentorship opportunities. Socialization tactics, or orientation tactics, are designed based on an organization's needs, values, and structural policies. Organizations either favor a systematic approach to socialization, or a "sink or swim" approach- in which new employees are challenged to figure out existing norms and company expectations without guidance.

Van Maanen and Schein model (1979)

John Van Maanen and Edgar H. Schein have identified six major tactical dimensions that characterize and represent all of the ways in which organizations may differ in their approaches to socialization.

Collective and individual socialization

Collective socialization is the process of taking a group of new hires, and giving them the same training. Examples of this include: basic training/boot camp for a military organization, pledging for fraternities/sororities, and education in graduate schools. Individual socialization allows newcomers to experience unique training, separate from others. Examples of this process include but are not limited to: apprenticeship programs, specific internships, and "on-the-job" training.[23]

- Formal and informal socialization

Formal socialization refers to when newcomers are trained separately from current employees within the organization. These practices single out newcomers, or completely segregate them from the other employees. Formal socialization is witnessed in programs such as police academies, internships, and apprenticeships. Informal socialization processes involve little to no effort to distinguish the two groups. Informal tactics provide a less intimidating environment for recruits to learn their new roles via trial and error. Examples of informal socialization include on-the-job training assignments, apprenticeship programs with no clearly defined role, and using a situational approach in which a newcomer is placed into a work group with no recruit role.[23]

- Sequential and random socialization

Sequential socialization refers to the degree to which an organization provides identifiable steps for newcomers to follow during the onboarding process. Random socialization occurs when the sequence of steps leading to the targeted role are unknown, and the progression of socialization is ambiguous; for example, while there are numerous steps or stages leading to specific organizational roles, there is no specific order in which the steps should be taken.[23]

- Fixed and variable socialization

This dimension refers to whether or not the organization provides a timetable to complete socialization. Fixed socialization provides a new hire with the exact knowledge of the time it will take to complete a given passage. For instance, some management trainees can be put on "fast tracks", where they are required to accept assignments on an annual basis, despite their own preferences. Variable techniques allow newcomers to complete the onboarding process when they feel comfortable in their position. This type of socialization is commonly associated with up-and-coming careers in business organizations; this is due to several uncontrollable factors such as the state of the economy or turnover rates which determine whether a given newcomer will be promoted to a higher level or not.[23]

- Serial and disjunctive socialization

A serial socialization process refers to experienced members of the organization mentoring newcomers. One example of serial socialization would be a first-year police officer being assigned patrol duties with an officer who has been in law enforcement for a lengthy period of time. Disjunctive socialization, in contrast, refers to when newcomers do not follow the guidelines of their predecessors; no mentors are assigned to inform new recruits on how to fulfill their duties.[23]

- Investiture and divestiture socialization

This tactic refers to the degree to which a socialization process either confirms or denies the personal identities of the new employees. Investiture socialization processes document what positive characteristics newcomers bring to the organization. When using this socialization process, the organization makes use of their preexisting skills, values, and attitudes. Divestiture socialization is a process that organizations use to reject and remove the importance of personal characteristics a new hire has; this is meant to assimilate them with the values of the workplace. Many organizations require newcomers to sever previous ties, and forget old habits in order to create a new self-image based upon new assumptions.[23]

Thus, tactics influence the socialization process by defining the type of information newcomers receive, the source of this information, and the ease of obtaining it.[23]

Jones' model (1986)

Building on the work of Van Maanen and Schein, Jones (1986) proposed that the previous six dimensions could be reduced to two categories: institutionalized and individualized socialization. Companies that use institutionalized socialization tactics implement step-by-step programs, have group orientations, and implement mentor programs. One example of an organization using institutionalized tactics include incoming freshmen at universities, who may attend orientation weekends before beginning classes. Other organizations use individualized socialization tactics, in which the new employee immediately starts working on his or her new position and figures out company norms, values, and expectations along the way. In this orientation system, individuals must play a more proactive role in seeking out information and initiating work relationships.[24]

Formal orientations

Regardless of the socialization tactics used, formal orientation programs can facilitate understanding of company culture, and introduces new employees to their work roles and the organizational social environment. Formal orientation programs consist of lectures, videotapes, and written material. More recent approaches, such as computer-based orientations and Internets, have been used by organizations to standardize training programs across branch locations. A review of the literature indicates that orientation programs are successful in communicating the company's goals, history, and power structure.[25]

Recruitment events

Recruitment events play a key role in identifying which potential employees are a good fit for an organization. Recruiting events allow employees to gather initial information about an organization's expectations and company culture. By providing a realistic job preview of what life inside the organization is like, companies can weed out potential employees who are clearly a misfit to an organization; individuals can identify which employment agencies are the most suitable match for their own personal values, goals, and expectations. Research has shown that new employees who receive a great amount of information about the job prior to being socialized tend to adjust better.[26] Organizations can also provide realistic job previews by offering internship opportunities.

Mentorship

Mentorship has demonstrated importance in the socialization of new employees.[27][28] Ostroff and Kozlowski (1993) discovered that newcomers with mentors become more knowledgeable about the organization than did newcomers without. Mentors can help newcomers better manage their expectations and feel comfortable with their new environment through advice-giving and social support.[29] Chatman (1991) found that newcomers are more likely to have internalized the key values of their organization's culture if they had spent time with an assigned mentor and attended company social events. Literature has also suggested the importance of demographic matching between organizational mentors and mentees.[27] Enscher & Murphy (1997) examined the effects of similarity (race and gender) on the amount of contact and quality of mentor relationships.[30] What often separates rapid onboarding programs from their slower counterparts is not the availability of a mentor, but the presence of a "buddy", someone the newcomer can comfortably ask questions that are either trivial ("How do I order office supplies?") or politically sensitive ("Whose opinion really matters here?").[31] Buddies can help establish relationships with co-workers in ways that can't always be facilitated by a newcomer's manager.[32]

Employee adjustment

Role clarity

Role clarity describes a new employee's understanding of their job responsibilities and organizational role. One of the goals of an onboarding process is to aid newcomers in reducing uncertainty, making it easier for them to get their jobs done correctly and efficiently. Because there often is a disconnect between the main responsibilities listed in job descriptions and the specific, repeatable tasks that employees must complete to be successful in their roles, it's vital that managers are trained to discuss exactly what they expect from their employees.[33] A poor onboarding program may produce employees who exhibit sub-par productivity because they are unsure of their exact roles and responsibilities. A strong onboarding program produces employees who are especially productive; they have a better understanding of what is expected of them. Organizations benefit from increasing role clarity for a new employee. Not only does role clarity imply greater productivity, but it has also been linked to both job satisfaction and organizational commitment.[34]

Self-efficacy

Self-efficacy is the degree to which new employees feel capable of successfully completing and fulfilling their responsibilities. Employees who feel they can get the job done fare better than those who feel overwhelmed in their new positions; research has found that job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and turnover are all correlated with feelings of self-efficacy.[4] Research suggests social environments that encourage teamwork and employee autonomy help increase feelings of competence; this is also a result of support from co-workers, and managerial support having less impact on feelings of self-efficacy.[35] Management can work to increase self-efficacy in several ways. One includes having clear expectations of employees, with consequences for failing to meet the requirements. Management can also offer programs to enhance self-efficancy by emphasizing the ability of employees to use their existing tools and skills to solve problems and complete tasks.[36]

Social acceptance

Social acceptance gives new employees the support needed to be successful. While role clarity and self-efficacy are important to a newcomer's ability to meet the requirements of a job, the feeling of "fitting in" can do a lot for one's view of the work environment and has been shown to increase commitment to an organization and decrease turnover.[4] In order for onboarding to be effective employees must help in their own onboarding process by interacting with other coworkers and supervisors socially, and involving themselves in functions involving other employees.[37] The length of hire also determines social acceptance, often by influencing how much an employee is willing to change to maintain group closeness. Individuals who are hired with an expected long-term position are more likely to work toward fitting in with the main group, avoiding major conflicts. Employees who are expected to work in the short-term often are less invested in maintaining harmony with peers. This impacts the level of acceptance from existing employee groups, depending on the future job prospects of the new hire and their willingness to fit in.[38]

Identity impacts social acceptance as well. If an individual with a marginalized identity feels as if they are not accepted, they will suffer negative consequences. It has been show that when LGBT employees conceal their identities at work they are a higher risk for mental health problems, as well as physical illness.[39][40] They are also more likely to experience low satisfaction and commitment at their job.[41][42] Employees possessing disabilities may struggle to be accepted in the workplace due to coworkers' beliefs about the capability of the individual to complete their tasks.[43] Black employees who are not accepted in the workplace and face discrimination experience decreased job satisfaction, which can cause them to perform poorly in the workplace resulting in monetary and personnel costs to organizations.[44]

Knowledge of organizational culture

Knowledge of organizational culture refers to how well a new employee understands a company's values, goals, roles, norms, and overall organizational environment. For example, some organizations may have very strict, yet unspoken, rules of how interactions with superiors should be conducted or whether overtime hours are the norm and an expectation. Knowledge of one's organizational culture is important for the newcomer looking to adapt to a new company, as it allows for social acceptance and aids in completing work tasks in a way that meets company standards. Overall, knowledge of organizational culture has been linked to increased satisfaction and commitment, as well as decreased turnover.[45]

Outcomes

Historically, organizations have overlooked the influence of business practices in shaping enduring work attitudes and have underestimated its impact on financial success.[46] Employees' job attitudes are particularly important from an organization's perspective because of their link to employee engagement and performance on the job. Employee engagement attitudes, such as organizational commitment or satisfaction, are important factors in an employee's work performance. This translates into strong monetary gains for organizations. As research has demonstrated, individuals who are satisfied with their jobs and show organizational commitment are likely to perform better and have lower turnover rates.[46][47] Unengaged employees are very costly to organizations in terms of slowed performance and potential rehiring expenses. With the onboarding process, there can be short term and long term outcomes. Short term outcomes include: self-efficacy, role clarity, and social integration. Self-efficacy is the confidence a new employee has when going into a new job. Role clarity is the expectation and knowledge they have about the position. Social integration is the new relationships they form, and how comfortable they are in those relationships, once they have secured that position. Long term outcomes consist of organizational commitment, and job satisfaction. How satisfied the employee is after onboarding, can either help the company, or prevent it from succeeding.[48]

Limits and criticisms of onboarding theory

The outcomes of organizational socialization have been positively associated with the process of uncertainty reduction, but are not desirable to all organizations. Jones (1986) and Allen and Meyer (1990) found that socialization tactics were related to commitment, but negatively correlated to role clarity.[24][49] Because formal socialization tactics protect the newcomer from their full responsibilities while "learning the ropes," there is a potential for role confusion once the new hire fully enters the organization. In some cases, organizations desire a certain level of person-organizational misfit in order to achieve outcomes via innovative behaviors.[9] Depending on the culture of the organization, it may be more desirable to increase ambiguity, despite the potentially negative connection with organizational commitment.

Additionally, socialization researchers have had major concerns over the length of time that it takes newcomers to adjust. There has been great difficulty determining the role that time plays, but once the length of the adjustment is determined, organizations can make appropriate recommendations regarding what matters most in various stages of the adjustment process.[9]

Further criticisms include the use of special orientation sessions to educate newcomers about the organization and strengthen their organizational commitment. While these sessions have been found to be formal and ritualistic, studies have found them unpleasant or traumatic.[50] Orientation sessions are a frequently used socialization tactic, however, employees have not found them to be helpful, nor has any research provided any evidence for their benefits.[51][52][53][54][55]

Executive onboarding

Executive onboarding is the application of general onboarding principles to helping new executives become productive members of an organization. It involves acquiring, accommodating, assimilating and accelerating new executives.[56] Hiring teams emphasize the importance of making the most of the new hire's "honeymoon" stage in the organization, a period which described as either the first 90 to 100 days, or the first full year.[57][58][59]

Effective onboarding of new executives is an important contribution hiring managers, direct supervisors or human resource professionals make to long-term organizational success; executive onboarding done right can improve productivity and executive retention, and build corporate culture. 40 percent of executives hired at the senior level are pushed out, fail, or quit within 18 months without effective socialization.[60]

Onboarding is valuable for externally recruited, or those recruited from outside the organization, executives. It may be difficult for those individuals to uncover personal, organizational, and role risks in complicated situations when they lack formal onboarding assistance.[61] Onboarding is also an essential tool for executives promoted into new roles and/or transferred from one business unit to another.[62]

Socialization in online organizations

The effectiveness of socialization varies depending on the structure and communication within the organization, and the ease of joining or leaving the organization.[63] These are dimensions that online organizations differ from conventional ones. This type of communication makes the development and maintenance of social relationships with other group members difficult to accomplish, and weaken organizational commitment.[64][65] Joining and leaving online communities typically involves less cost than a conventional employment organization, which results in lower level of commitment.[66]

Socialization processes in most online communities are informal and individualistic, as compared with socialization in conventional organizations.[67] For example, lurkers in online communities typically have no opportunities for formal mentorship, because they are less likely to be known to existing members of the community. Another example is WikiProjects, the task-oriented group in Wikipedia, rarely use institutional socialization tactics to socialize new members who join them,[68] as they rarely assign the new member a mentor or provide clear guidelines. A third example is the socialization of newcomers to the Python open-source software development community.[69] Even though there exists clear workflows and distinct social roles, socialization process is still informal.

Recommendations for practitioners

Scholars at MIT Sloan, suggest that practitioners should seek to design an onboarding strategy that takes individual newcomer characteristics into consideration and encourages proactive behaviors, such as information seeking, that help facilitate the development of role clarity, self-efficacy, social acceptance, and knowledge of organizational culture. Research has consistently shown that doing so produces valuable outcomes such as high job satisfaction (the extent to which one enjoys the nature of his or her work), organizational commitment (the connection one feels to an organization), and job performance in employees, as well as lower turnover rates and decreased intent to quit.[70]

In terms of structure, evidence shows that formal institutionalized socialization is the most effective onboarding method.[25] New employees who complete these kinds of programs tend to experience more positive job attitudes and lower levels of turnover in comparison to those who undergo individualized tactics.[9][71] Evidence suggests that in-person onboarding techniques are more effective than virtual ones. Though it initially appears to be less expensive for a company to use a standard computer-based orientation programs, research has demonstrated that employees learn more about their roles and company culture through face-to-face orientation.[72]

See also

- Employment

- Employee offboarding

- Employee engagement

- Employee motivation

- Industrial and organizational psychology

- Induction programme

- Job Shadowing

- Job performance

- Job satisfaction

- Mentoring

- Business networking

- Organizational commitment

- Organizational culture

- Personnel psychology

- Realistic job preview

- Recruitment

- Socialization

- Personality–job fit theory

- Person–environment fit

References

- "What is onboarding".

- Ashford, S. J., & Black, J. S. (1996). Proactivity during organizational entry: The role of desire for control. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81, 199–214.

- Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D., & Wanberg, C. R. (2003). Unwrapping the organizational entry process: Disentangling multiple antecedents and their pathways to adjustment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 779–794.

- Fisher, C. D. (1985). Social support and adjustment to work: A longitudinal study. Journal of Management, 11, 39–53.

- Rollag, K., Parise, S., & Cross, R. (2005). Getting new hires up to speed quickly. MIT Sloan Management Review, 46, 35–41.

- "Online Training and Inductions as a Medium". onlineinduction.com. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- "training". The Free Dictionary.

- Bauer, T. N., Bodner, T., Erdogan, B., Truxillo, D. M., & Tucker, J. S. (2007). Newcomer adjustment during organizational socialization: A meta-analytic review of antecedents, outcomes and methods. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 707–721.

- Saks, A. M., & Ashforth, B. E. (1996). Proactive socialization and behavioral self-management. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 48, 301–323.

- Erdogan, B., & Bauer, T. N. (2009). Perceived overqualification and its outcomes: The moderating role of empowerment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94, 557–565.

- Crant, J. M. (2000). Proactive behavior in organizations. Journal of Management, 26, 274–276.

- Litman, J.A. (2005). Curiosity and the pleasures of learning: Wanting and liking new information. Cognition & Emotion, 19, 793–814.

- Ashford, S.J., & Cummings, L.L. (1983). Feedback as an individual resource: Personal strategies of creating information. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 32,370–398.

- Beyer, J. M., & Hannah, D. R. (2002). Building on the past: Enacting established personal identities in a new work setting. Organizational Science, 13, 636–652..

- Kirschenbaum, S. S., (1992). Influence of experience on information-gathering strategies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 77, 343–352.

- Meglino, B., DeNisi, A., & Ravlin, E. (1993). Effects of previous job exposure and subsequent job status on the functioning of a realistic job preview. Personnel Psychology, 46, 803–822.

- Carr, J. C., Pearson, A. W., West, M. J., & Boyar, S. L. (2006). Prior occupational experience, anticipatory socialization, and employee retention. Journal of Management, 32, 343–359.

- Miller, V. D., & Jablin, F. M., (1991). Information seeking during organizational entry: Influences, tactics, and a model of the process. Academy of Management Review, 16, 92–120.

- Menguc, B., Han, S. L., & Auh, S. (2007). A test of a model of new salespeople's socialization and adjustment in a collectivist culture. Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management, 27, 149–167.

- Wanberg, C. R., & Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D. (2000). Predictors and outcomes of proactivity in the socialization process. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 373–385.

- Morrison, E. W., Chen, Y., & Salgado, S. R. (2004). Cultural differences in newcomer feedback seeking: A comparison of the United States and Hong Kong. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 53, 1–22.

- Van Maanen, J., & Schein, E. H. (1979). Toward a theory of organizational socialization. Research in Organizational Behavior, 1, 209–264.

- Jones, G. R. (1986). Socialization tactics, self-efficacy, and newcomers' adjustments to organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 29, 262–279.

- Bauer, T. N. (2010). Onboarding new employees: Maximizing success. SHRM Foundation's Effective Practice Guideline Series.

- Klein, H. J., Fan, J., & Preacher, K. J. (2006). The effects of early socialization experiences on content mastery and outcomes: A mediational approach. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 68, 96–115.

- Chatman, J. A. (1991). Matching people and organizations: Selection and socialization in public accounting firms. Administrative Science Quarterly, 36, 459–484.

- Major, D. A., Kozlowski, S. W. J., Chao, G. T., & Gardner, P. D. (1995). A longitudinal investigation of newcomer expectations, early socialization outcomes, and the moderating effects of role development factors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 80, 418–431.

- Ostroff, C., & Kozlowski, S. W. J. (1993). The role of mentoring in the information gathering processes of newcomers during early organizational socialization. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 42, 170–183.

- Enscher, E. A., Murphy, S. E., (1997). Effects of race, gender, perceived similarity, and contact on mentor relationships. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 50, 460–481.

- Rollag, K.; Parise, S.; Cross, R. (2005). "Getting New Hires Up to speed Quickly". MIT Sloan Management Review. 46 (2): 35–41.

- Rollag, K; Parise, S.; Cross, R. (2005). "Gettin New Hires Up to Speed Quickly". MIT Sloan Management Review. 46 (2): 35–41.

- Vernon, A. (2012). "New-Hire Onboarding: Common Mistakes to Avoid". T+D. 66 (9): 32–33.

- Adkins, C. L. (1995). Previous work experience and organizational socialization: A longitudinal examination. Academy of Management Journal, 38, 839–862.

- Jungert, T., Koestner, R. F., Houlfort, N., & Shattke, K. (2013). Distinguishing Source of Autonomy Support in Relation to Worker's Motivation and Self-Efficacy. The Journal of Social Psychology, 153:6, 651-666.

- Stajkovic, A. D., & Luthans, F. (1998). Self-efficacy and work-related performance: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 124(2), 240-261.

- Bauer, T. N. (2010). Onboarding new employees: Maximizing success. SHRM Foundation's Effective Practice Guideline Series.

- Rink, F. A., & Ellemers, N. (2009). Temporary versus permanent group membership: how the future prospects of newcomers affect newcomer acceptance and newcomer influence. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 35(6), 764–775.

- Frable, E. S. D., & Platt, L., & Hoey, S. (1998). Concealable Stigmas and Positive Self-Perceptions: Feeling Better Around Similar Others. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(4), 909-922.

- Cole, S. W., Kemeny, M. E., Taylor, S. E., & Visscher, B. R. (1996). Elevated Physical Health Risk Among Gay Men Who Conceal Their Homosexual Identity. Health Psychology, 15(4), 243–251.

- Griffith, K. H., & Hebl, M. R. (2002). The Disclosure Dilemma for Gay Men and Lesbians: "Coming Out" at Work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(6), 1191–1199.

- Newheiser, A. K., Barreto, M., & Tiemersma, J. (2017). People Like Me Don't Belong Here: Identity Concealment is Associated with Negative Workplace Experiences. Journal of Social Issues, 73(2), 341–358.

- Mclaughlin, M. E., Bell, M. P., & Stringer, D. Y., (2004). Stigma and Acceptance of Persons With Disabilities. Group and Organization Management, 29(3), 302–333.

- Deitch, E. A., Barksy, A., Butz, R. M., Chan, S., Breif, A. P., & Bradly, J. C. (2003). Subtle yet significant: The existence and impact of everyday racial discrimination in the workplace. Human Relations, 56(11), 1299–1324.

- Klein, H. J., & Weaver, N. A. (2000). The effectiveness of an organizational-level orientation training program in the socialization of new hires. Personnel Psychology, 53, 47–66.

- Saari, L. M. & Judge, T. A. (2004). Employee attitudes and job satisfaction. Human Resource Management, 43, 395–407.

- Ryan, A. M., Schmit, M. J., & Johnson, R. (1996). Attitudes and effectiveness: Examining relations at an organizational level. Personnel Psychology, 49, 853–882.

- Bauer, T. N. (2007). "Onboading new employees: maximizing success". SHRM Foundation's Effective Practice Guidelines Series: 1–37.

- Allen, N.J., & Meyer, J.P. (1990). Organizational socialization tactics: A longitudinal analysis of links to newcomers' commitment and role orientation. Acadmeny of Management Journal, 33, 847–858

- Rohlen, T.P. (1973). "Spiritual education" in a Japanese bank. American Anthropologist, 75, 1542–1562.

- Louis, M.R., Posner, B.Z., & Powell, G.N. (1983). The availability and helpfulness of socialization practices. Personnel Psychology, 36, 857–866.

- Nelson, D.L., & Quick, J.C. (1991). Social support and newcomer adjustment in organizations: Attachment theory at work? Journal of Organizational Behavior, 12, 543–554.

- Posner, B.Z., & Powell, G.N. (1985). Female and male socialization experiences: an initial investigation. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 70, 81–85.

- Saks, A.M. (1994). Moderating effects of self-efficacy for the relationship between training method and anxiety and stress reductions of newcomers. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 15, 639–654.

- Wanous, J.P. (1993). Newcomer orientation programs that facilitate organizational entry. In organizational perspectives (pp. 125–139). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Bradt, George; Mary Vonnegut (2009). Onboarding: How To Get Your New Employees Up To Speed In Half The Time. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-48581-1.

- Watkins, Michael (2003). The First 90 Days. Harvard Business School Publishing. ISBN 1-59139-110-5.

- "That tricky first 100 days". The Economist. July 15, 2006.

- Stein, Christiansen (2010). Successful Onboarding: Strategies to Unlock Hidden Value Within Your Organization. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-173937-5.

- Masters, Brooke (March 30, 2009). "Rise of a Headhunter". Financial Times.

- Bradt, George (2009) [2006]. The New Leader's 100-Day Action Plan (revised ed.). J. Wiley and Sons. ISBN 0-470-40703-4.

- Watkins, Michael (2009). Your Next Move. Harvard Business School Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4221-4763-4.

- Ashforth, B. K., & Saks, A. M. (1996). Socialization tactics: Longitudinal effects on newcomer adjustment. Academy of management Journal, 39(1), 149–178.

- Kiesler, S., Siegel, J., & McGuire, T. W. (1984). Social psychological aspects of computer-mediated communication. American psychologist, 39(10), 1123.

- Ren, Y., Kraut, R., & Kiesler, S. (2007). Applying common identity and bond theory to design of online communities. Organization studies, 28(3), 377–408.

- Allen, N. J., & Meyer, J. P. (1990). The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. Journal of occupational and organizational psychology, 63(1), 1–18.

- Kraut, R. E., Resnick, P., Kiesler, S., Burke, M., Chen, Y., Kittur, N., ... & Riedl, J. (2012). Instead, online communities generally adopt individualized socialization tactics or none at all. Building successful online communities: Evidence-based social design. Mit Press. Chicago.

- Choi, B., Alexander, K., Kraut, R. E., & Levine, J. M. (2010, February). Socialization tactics in Wikipedia and their effects. In Proceedings of the 2010 ACM conference on Computer supported cooperative work (pp. 107–116). ACM.

- Ducheneaut, N. (2005). Socialization in an open source software community: A socio-technical analysis. Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW), 14(4), 323–368.

- Cable, D. M., Gino, F., & Staats, B. R. (2013). Reinventing employee onboarding. MIT Sloan Management Review, 54(3), 23.

- Saks, A. M., Uggerslev, K. L., & Fassina, N. E. (2007). Socialization tactics and newcomer adjustment: A meta-analytic review and test of a model. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 70, 413–446.

- Wesson, M. J., & Gogus, C. I. (2005). Shaking hands with a computer: An examination of two methods of organizational newcomer orientation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 1018–1026.

Further reading

- Ashforth, B. E., & Saks, A. M. (1996). Socialization tactics: Longitudinal effects on newcomer adjustment. Academy of Management Journal, 39, 149–178.

- Foste, E. A., & Botero, I. C. (2012). Personal Reputation: Effects of Upward Communication on Impressions About New Employees. Management Communication Quarterly, 26(1), 48–73. doi:10.1177/0893318911411039.

- Gruman, J. A., Saks, A. M., & Zweig, D. L. (2006). Organizational socialization tactics and newcomer proactive behaviors: An integrative study. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 69, 90–104.

- Klein, H. J., Fan, J., & Preacher, K. J. (2006). The effects of early socialization experiences on content mastery and outcomes: A mediational approach. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 68, 96–115.

- Van Maanen, J. and Schein, E, H. 1979. Toward a Theory of Organizational Socialization. In B. M. Staw(Ed.) Research in Organizational Behavior, 1, pp. 209–264, Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.