False advertising

False advertising is the use of false, misleading, or unproven information to advertise products to consumers. The advertising frequently does not disclose its source.[1][2] One form of false advertising is to claim that a product has a health benefit or contains vitamins or minerals that it in fact does not.[3] Many governments use regulations to control false advertising. A false advertisement can further be classified as deceptive if the advertiser deliberately misleads the consumer, as opposed to making an honest mistake.

Types of deception

Photo bleaching

Often used in cosmetic and weight loss commercials,[4] these adverts portray false and unobtainable results to the consumer and give a false impression of the product's true capabilities. If retouching is not discovered or fixed, a company can be at a competitive advantage with consumers purchasing their seemingly more effective product, thereby leaving competitors at a loss.

Advertisers for weight loss products may also employ athletes who are recovering from injuries for "before and after" demonstrations. Cosmetics advertisements often use photo manipulation or computer-generated imagery to promote products, which do not reflect the real effect of the products.[5]

Omitting information

An ad may omit or skim over important information. The ad's claims may be technically true, but the ad does not include information that a reasonable person would consider relevant. For example, TV advertisements for prescription drugs may technically fulfill a regulatory requirement by displaying side-effects in a small font at the end of the ad, or have a "speed-talker" list them. This practice was prevalent in the United States in the recent past.

Hidden fees and surcharges

Hidden fees can be a way for companies to trick the unwary consumer into paying excess fees (for example tax, shipping fees, insurance etc.) on a product that was advertised at a specific price as a way to increase profit without raising the price on the actual item.[6][7]

A common form of hidden fees and surcharges is "fine print" in advertising. Another way to hide fees that is commonly used is to not include "shipping fees" into the price of goods online. This makes an item look cheaper than it is once the shipping cost is added.[8] Many hotels charge mandatory "resort fees" that are not typically included in the advertised base price of the room.

Manipulation of measurement units and standards

Manipulation of measurement units and standards can be described as a seller deceiving customers by informing them with facts that either are not true or are using a standard or standards that wouldn't be widely used or understood which results in the customer being misinformed or confused.

A form of measurement manipulation is when a company will repackage a product in the same sized container, but will advertise it as being "family size" or "bonus size" even though it contains the same amount of product.[9] This is very common with liquid products like soaps that are sold in grocery stores.

Fillers and oversized packaging

Some products are sold with fillers, which increase the legal weight of the product with something that costs the producer very little compared to what the consumer thinks that he or she is buying. Food is an example of this, where meat is injected with broth or even brine (up to 15%), or TV dinners are filled with gravy or other sauce instead of meat. Malt and ham have been used as filler in peanut butter.[10] There are also non-meat fillers which may look starchy in their makeup; they are high in carbohydrates and low in nutritional value. One example is known as a cereal binder and usually contains some combination of flours and oatmeal.[11]

Some products may have a large container where most of the space is empty, leading the consumer to believe that the total amount of food is greater than it actually is.[12]

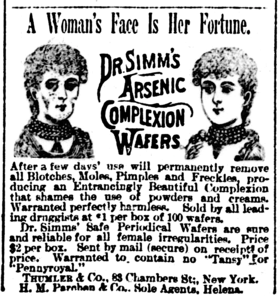

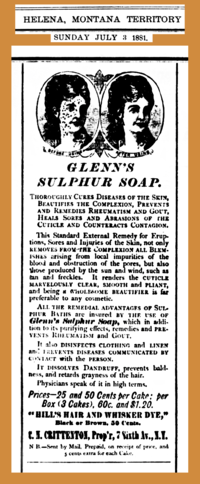

Misleading health claims

Right: Sulfur is known to have antifungal, antibacterial, and keratolytic activity; in the past it was used against acne vulgaris, rosacea, seborrheic dermatitis, dandruff, pityriasis versicolor, scabies, and warts.[15] This 1881 advertisement claims efficacy against rheumatism, gout, baldness, and graying of hair.

One claims to restore "perfect manhood. Failure is impossible with our method". Another "will quickly cure you of all nervous or diseases of the generative organs, such as Lost Manhood, Insomnia, Pains in the Back, Seminal Emissions, Nervous Debility, Pimples, Unfitness to Marry, Exhausting Drains, Varicocele and Constipation".[16]

The words "diet, low fat, sugar-free, healthy and good for you" are labels a consumer may see often on packaging, and thus associate these labels with products that will aid in a healthy lifestyle. It seems advertisers are aware of the need to live healthier and longer, so they adapt their products in accordance. It is suggested that food advertising influences consumer preferences and shopping habits.[17] Therefore, by highlighting certain contents or ingredients is misleading consumers into thinking they are buying healthy when in fact they are not.[18] Dannon's Activia yogurt was advertised as clinically and scientifically proven to boost the immune system and was being sold at a much higher price because of the claim. The company was asked to pay $45 million in damages to the consumers after a lawsuit was filed against it.[19]

Many large food companies are going to court after using misleading tactics like these:[20]

- Using a tick panel above the nutritional label and using large, bold font and brighter colors.[20]

- Highlighting one healthy ingredient on the front of the packet with a big tick next to it.[20]

- Using words like healthy and natural which are weasel claims – words that contradict the claims that may follow it. These are commonly used words where the meaning can be overlooked by consumers.[21][22]

- Using words like help on the product labeling, misleading consumers into thinking it ‘will’ help.[20][23]

This is not always the case. There has been an increase in the number of large organizations going to court over misleading claims, stating that products are ‘school canteen approved’ or ‘all natural,’ hence claiming their products are healthy or only uses natural ingredients, but this is not always the case.[24]

Also, many advertisements for supplements or medicine include "This product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.",[25] as any product that is intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease must undergo FDA testing and approval, which is usually very expensive. False drug advertisements can affect the health of people. Few drug advertisements mention the harm of the product, but just emphasize the efficacy of the drug.[26]

Comparative advertising

In the world of advertising, companies employ a gamut of marketing techniques in order to assert their products as the best available on the market. One of the most common marketing tactics in this space is known as ‘comparative advertising’ where “the advertised brand is explicitly compared with one or more competing brands and the comparison is obvious to the audience.”[27] The laws surrounding comparative advertising have changed immensely over the history of law in the United States, with perhaps the most drastic change occurring with the creation of the Lanham Act in 1946. The Lanham Act has served as the backbone and official canon for all cases that reference or involve false advertisement. Over the years, marketing strategies have become progressively more aggressive, and the limitations of the Lanham Act became outdated.

In 2012, USCA §1125 was passed as an addition to the Lanham Act, and clarified questions about comparative advertising. Under §1125, anyone who, in commerce, uses words, symbols, or misleading descriptions of fact that are either likely to cause confusion within consumers about their own product, or in commercial advertising misrepresents the nature, characteristics, or qualities of their own or another’s product is liable under a civil action by anyone who is damaged by the act.[28] USCA §1125 resolves some of the gaps in the Lanham Act, but it still does not suffice as a perfect remedy for every case that may arise. For now, advertisements that present false descriptions of fact are considered deceptive with no additional evidence required. When an advertisement makes a factual but misleading claim, further evidence of the actual confusion of an average consumer is needed.[29]

Puffing

Puffing or puffery is the act of exaggerating a product's worth through the use of meaningless unsubstantiated terms, based on opinion rather than fact,[30] and in some cases through the manipulation of data.[31] Examples of this include many superlatives and statements such as "greatest of all time", "best in town" and "out of this world" or a restaurant claiming it had "the world’s best tasting food".[32] Puffing has an impact on life. One example of this is the impact of exaggerated campaign advertising during elections on voter turnout.[33]

Typically puffing is not an illegal form of false advertising and can be looked at as a humorous way to grab and attract the attention of the consumer.[32] Puffing may be able to be used as a defense against charges of deceptive advertising when it is formatted as an opinion rather than a fact.[34]

It can also be used as a defense for misleading or deceptive advertising. One example are claims like ‘Top Quality’ can have regulatory and legal consequences and can be looked at as illegal misrepresentation, if not supported through the product's capabilities.[35][36]

Manipulation of terms

Many terms have imprecise meanings. Depending on the jurisdiction, "organic" food may not have a clear legal definition, and "light" food has been variously used to mean low in calories, sugars, carbohydrates, salt, texture, viscosity, or even light in color. Labels such as "all-natural" are frequently used but are essentially meaningless in a legal sense.

Prior to the landmark case against 'big tobacco', and the resulting settlement, tobacco companies regularly used terms like low tar, light, ultra-light and mild in order to imply that products with such labels had less detrimental effects on health, but in 2009 the United States banned manufacturers from labeling tobacco products with these terms.[37]

When the US United Egg Producers' used an "Animal Care Certified" logo on egg cartons, the Better Business Bureau argued that it misled consumers by conveying a higher sense of animal care than was actually the case.[38]

In 2010, Kellogg's Rice Krispies cereal claimed that the cereal can improve a child's immunity. The company was forced to discontinue all advertising stating such claims.[39] In 2015 the same company advertised their Kashi product as "all natural", when it contained a variety of synthetic and artificial ingredients; Kellogg's paid $5 million to resolve the issue.[40]

Incomplete comparison

"Better" means one item is superior to another in some way, while "best" means it is superior to all others in some way. However, advertisers frequently fail to list the way in each they are being compared (price, size, quality, etc.) and, in the case of "better", to what they are comparing (a competitor's product, an earlier version of their own product, or nothing at all). So, without defining how they are using the terms better and best, the terms become meaningless. An ad which claims "Our cold medicine is better" could be just saying it is an improvement over taking nothing at all. Another often-seen example of this ploy is "better than the leading brand" often with some statistic attached, while the leading brand is often left undefined.

Inconsistent comparison

In an inconsistent comparison, an item is compared with many others, but only compared with each on the attributes where it wins, leaving the false impression that it is the best of all products, in all ways. One variation on this theme is web sites which also list some competitor prices for any given search, but do not list those competitors which beat their price (or the web site might compare their own sale prices with the regular prices offered by their competitors).

Misleading illustrations

One common example is that of serving suggestion pictures on food product boxes, which show additional ingredients beyond those included in the package. Although the "serving suggestion" disclaimer is a legal requirement of an illustration which includes items not included in the purchase, if a customer fails to notice or understand this caption, they may incorrectly assume that all depicted items are all included.

In some advertised images of hamburgers, every ingredient is visible from the side shown in the advertisement, giving the impression that they are larger than they really are.[41] Products which are sold unassembled or unfinished may also have a picture of the finished product, without a corresponding picture of what the customer is actually buying.

Commercials for certain video games include trailers that are essentially CGI short-films - with graphics of a much higher caliber than the actual game.[42] This practice has been used more in recent years and has led to major backlash from video gaming communities.

False coloring

"The color of food packaging is considered to be extremely important in the marketing world" (Blackbird, Fox & Tornetta, 2013) as people see color before they absorb anything else. Consumers buy items based on the color they've seen it on the advertisement and they have a perception of what the packaging colors should also look like. When it comes to buying food, usually consumers can only judge the product based on the packaging and usually consumers judge products based on color.

When used to make people think food is riper, fresher, or otherwise healthier than it really is, food coloring can be a form of deception. When combined with added sugar or corn syrup, bright colors give the subconscious impression of healthy, ripe fruit, full of antioxidants and phytochemicals.

One variation is packaging which obscures the true color of the foods contained within, such as red mesh bags containing yellow oranges or grapefruit, which then appear to be a ripe orange or red. Regularly stirring minced meat on sale at a deli can also make the meat on the surface stay red, causing it to appear fresh, while it would quickly oxidize and brown, showing its true age, if left unstirred. Some sodas are also sold in colored bottles, when the actual product is clear.

Angel dusting

Angel dusting is a process where an ingredient which would be beneficial, in a reasonable quantity, is instead added in an insignificant quantity which will have no consumer benefit, so they can make the claim that it contains that ingredient, and mislead the consumer into expecting that they will gain the benefit. For example, a cereal may claim it contains "12 essential vitamins and minerals", but the amounts of each may be only 1% or less of the Reference Daily Intake, providing virtually no benefit to nutrition.

"Chemical free"

Many products come with some form of the statement "chemical free!" or "no chemicals!". As everything on Earth, save a few elementary particles formed by radioactive decay or present in minute quantities from solar wind and sunlight, is made of chemicals, it is impossible to have a chemical free product. The intention of this message is often to indicate the product contains no synthetic or exceptionally harmful chemicals, but as the word chemical itself has a stigma, it is often used without clarification.

Bait-and-switch

Bait-and-switch is a deceptive form of advertising or marketing tactic generally used to lure in customers into the store. A company will advertise their product at a very cheap and enticing price which will attract the customers (bait). However, the product the customer seeks is not available for various reasons, such as the company only having a limited quantity of product available for sale which was quickly sold out (switch). After which, the store/company will then try to sell something that is more expensive and valuable than what they originally advertised (upsell). Regardless of the fact that only a small percentage of the shoppers will actually buy the more expensive product, the advertiser using the bait remains to gain profit.[43]

Bait advertising is also commonly used in other contexts, for example, in online job advertisements by deceiving the potential candidate about working conditions, pay, or different variables. Airlines may be guilty of "baiting" their potential clients with a bargains, then increase the cost or change the notice to be that of a considerably more costly flight.[44]

Businesses are asked to remember a few guidelines to avoid charges of misleading or deceptive conduct:

- Reasonable timeframe, reasonable quantities - Businesses must supply publicized merchandise or services at the promoted cost for a sensible or expressed timeframe and in sensible or expressed amounts. There is no exact meaning of what is implied by a 'sensible timeframe' or 'sensible amounts'.

- Qualifying statements - General qualifying statements, for example, 'in store and online now' could at present still leave a business open to charges of bait advertising if sensible amounts of the publicized item are not accessible.[45]

- Advertising deadlines - Companies need to have good grounds to trust that the merchandise will be accessible

- Rain checks - When, through no shortcoming of its own, a business can't supply merchandise or services as promoted companies ought to have a framework set up to supply or acquire the supply of the merchandise or benefits at the promoted cost as quickly as time permits.

- Online claims - If a company is an online-based company, it is essential for them to keep everything on their website updated to avoid misleading customers.[46]

In some countries bait advertising can result in severe penalties.[47]

Guarantee without a remedy specified

If a company does not say what they will do if the product fails to meet expectations, then they are free to do very little. This is due to a legal technicality that states that a contract cannot be enforced unless it provides a basis not only for determining a breach but also for giving a remedy in the event of a breach.[48]

This is a common practice used within crowdfunding communities like "Indiegogo" and "Kickstarter".[49]

"No risk"

Advertisers frequently claim there is no risk to trying their product, when clearly there is. For example, they may charge the customer's credit card for the product, offering a full refund if not satisfied. However, the risks of such an offer are numerous. Customers may not get the product at all, they may be billed for things they did not want, they may need to call the company to authorize a return and be unable to do so, they may not be refunded the shipping and handling costs, or they may be responsible for the return shipping.

Similarly, a ‘free trial’ is an advertising manoeuvre to have consumers become hands-on with the products or services before purchase, without any money spent but a free trial in exchange for credit cards details cannot be stated as a free trial, as there is a component of expenditure.[50][51]

Acceptance by default

This refers to a contract or agreement where no response is interpreted as a positive response in favor of the business. An example of this is where a customer must explicitly "opt out" of a particular feature or service, or be charged for that feature or service. Another example is where a subscription automatically renews unless the customer explicitly requests it to stop.

Regulation and enforcement

United States

In the United States, the federal government regulates advertising through the Federal Trade Commission[52] (FTC) with truth-in-advertising laws,[53] and additionally enables private litigation through various statutes, most significantly the Lanham Act (trademark and unfair competition).

The goal is prevention rather than punishment, reflecting the purpose of civil law in setting things right rather than that of criminal law. The typical sanction is to order the advertiser to stop its illegal acts, or to include disclosure of additional information that serves to avoid the chance of deception. Corrective advertising may be mandated,[54][55] but there are no fines or prison time except for the infrequent instances when an advertiser refuses to stop despite being ordered to do so.[56]

In 1905, Samuel Hopkins Adams released a series of papers detailing the misleading claims of the patent medicine industry. The public outcry sparked from the articles led to the created of the Food and Drug Administration in 1906.[57]

In 1941, the United States Supreme Court reviewed the Federal Trade Commission v. Bunte Bros LLC, under Section 5 in regards to Unfair or Deceptive Acts or Practices.[58]

In 2013 and 2014, the United States Supreme Court reviewed three false advertising cases: Static Control v. Lexmark (concerning who has standing to sue under the Lanham Act for false advertising), ONY, Inc. v. Cornerstone Therapeutics, Inc.,[59] and POM Wonderful LLC v. Coca-Cola Co..

State governments have a variety of unfair competition laws, which regulate false advertising, trademarks, and related issues. Many are very similar to that of the FTC, and in many cases copied so closely that they are known as "Little FTC Acts."[60] These laws also go by the terminology "Unfair, Deceptive, or Abusive Acts and Practices" Laws[61] (UDAAP or UDAP Laws) and can vary widely in the degree of protection they provide to consumers, according to the National Consumer Law Center.[62]

In California, one such statute is the Unfair Competition Law (UCL).[63] The UCL "borrows heavily from section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act" but has developed its own body of case law.[64]

United Kingdom

Advertising in the UK is managed under the Consumer Protection from Unfair Trading Regulations 2008[65] (CPR), effectively the successor to the Trade Descriptions Act 1968. It is designed to implement the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive, part of a common set of European minimum standards for consumer protection and legally bind advertisers in England, Scotland, Wales and parts of Ireland.[50][65] These regulations focus on business to consumer interactions. These are modelled by a table used for assessing unfairness, evaluations being made against four tests expressed in the regulations that indicate deceptive advertising:

- Contrary to the requirements of professional diligence

- False or deceptive practice in relation to a specific list of key factors

- Omission of material information (unclear or untimely information)

- Aggressive practice by harassment, coercion or undue influence

These factors of deceptive advertising are critically analysed as they may crucially impair a consumer's ability to make an informed decision, thereby limiting their freedom of choice.

This system resembles American practice as reflected by the FTC in terms of disallowing false and deceptive messaging, prohibition of unfair and unethical commercial practices and omitting important information, but it differs in monitoring aggressive sales practices (regulation seven) which included high-pressure sales practices that go beyond persuasion. Harassment and coercion are not defined but rather interpreted as any undue physical and psychological pressure (in advertising).

Even if proven cases of false advertising do not inevitably result in civil or criminal repercussions: the Office of Fair Trading states in the instance of false advertising, companies are not always faced with civil and criminal repercussions, it is based on the seriousness of the infringement and each case is analysed individually, allowing the standards authority to promote compliance with regards to their enforcement policies, priorities and available resources. Another area of departure from American practice relates to a general prohibition on the use of competitors' logotypes, trademarks or similar copy to that used in a competitor's own advertising by another, particularly when making a comparison.

Under CPR legislation, there are different standards authorities for each country:

- In England and Wales, standards offences are handled by the Local Authority Trading Standards Services (TSS)

- In Northern Ireland by the Department of Enterprise, Trade and Investment

- In Scotland, offences are evaluated by. and potentially prosecuted through, the Crown Office and the Procurator Fiscal Service on behalf of the Lord Advocate.

Australia

In Australia, Australian Competition and Consumer Commission also known as the ACCC, are responsible for ensuring all businesses and consumers act in accordance with the Australian Competition & Consumer Act 2010, as well as, fair trade and consumer protection laws (ACCC, 2016).[66]

Each state and territory have its own consumer protection agency or consumer affairs agency (ACCC 2016).

- ACT - Office of Fair Trading (OFT)[67]

- NSW - Fair Trading[68]

- Office of Fair Trading - Queensland[69]

- SA - Office of Consumer and Business Services (CBS)[70]

- Tasmanian - Consumer Affairs & Fair Trading[71]

- Consumer Affairs - Victoria (CAV)[72]

- WA - Department of Commerce[73]

The ACCC is designed to assist both consumers, businesses, industries and infrastructure within the country. The ACCC assists the consumer by making available the rights, regulations, obligations and procedures; for refund and return, complaints, faulty products and guarantees of products and services. They also assist businesses and industries by developing clear laws and guidelines in relation to unfair practices and misleading or deceptive conduct.[66]

There are many similarities in the laws and regulation between the Australian ACCC, the New Zealand FTA, the American FCT and United Kingdom CPR. The structure of these policies is to support fair trade and competition alongside offering the consumers exactly what they are selling, in order to reduce deceptive and false practices. However, it is not limited to these countries, as most countries have agreements with the International Consumer Protection and Enforcement Network or ICPEN.[74]

New Zealand

In New Zealand, the Fair Trading Act 1986 aims to promote fair competition and trading in the country.[75][76][76] The act prohibits certain conduct in trade, provides for the disclosure of information available to the consumer relating to the supply of goods and services and promotes product safety. Although the Act does not require businesses to provide all information to consumers in every circumstances, businesses are obliged to ensure the information they do provide is accurate, and important information is not kept from consumers.[75][77]

A range of selling methods that intend to mislead the consumer are illegal under the Fair Trading Act:[35][77] The Act also applies to certain activities whether or not the parties are 'in trade' – such as employment advertising, pyramid selling, and the supply of products covered by product safety and consumer information standards.[75]

Both consumers and businesses alike can rely on and take their own legal action under the Act. Consumers may contact the trader and utilize their rights which have been stated in the Act to make headway with the trader. If the issues are not resolved, the consumer or anyone else can take actions under the Act. The Commerce Commission is also empowered to take enforcement action and will do so when allegations are sufficiently serious to meet its enforcement criteria.

Additionally, there are currently five consumer information standards:[77]

- Country of Origin (Clothing and Footwear) Labeling – Regulations 1992

- Fibre Content Labeling - Regulations 2000

- Used Motor Vehicles - Regulations 2008

- Water Efficiency - Regulations 2010

See also

References

- "Dictionary 'Deceptive advertising'". American Marketing Association. Archived from the original on July 9, 2018. Retrieved December 14, 2017.

- "Deceptive Advertising Definition - Consumer | Laws.com". consumer.laws.com. Retrieved April 3, 2016.

- "Ribena-maker fined $217,500 for misleading vitamin C ads". The New Zealand Herald. March 27, 2007. ISSN 1170-0777. Retrieved April 3, 2016.

- "Airbrushed make-up ads banned for 'misleading'". BBC News. 2011.

- Scott, Linda M. (2015). "The Force of Beauty: Transforming French Ideas of Femininity by Holly Grout". Advertising & Society Review. 16 (3). doi:10.1353/asr.2015.0018. ISSN 1534-7311.

- "Illegal Price Advertising". July 21, 2015. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - "Surcharges And Hidden Fees - Fraud | Laws.com". Fraud.laws.com. Retrieved March 31, 2016.

- "Add-ons and hidden fees | Commerce Commission". Comcom.govt.nz. Archived from the original on March 20, 2018. Retrieved March 31, 2016.

- "Cetaphil Class Action Says 'Bonus Size' Lotion is No Bonus at All". Top Class Actions. April 28, 2017. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- Wallechinsky, David (1975). The People's Almanac. Garden City: Doubleday. p. 1010. ISBN 0-385-04060-1.

- "Food Fillers 101". July 21, 2009.

- "O.C. DA's lawsuit may force Axe hair products to redesign containers". April 24, 2015.

- "A Woman's Face is Her Fortune (advertisement)". The Helena Independent. November 9, 1889. p. 7.

- Little, Becky (September 22, 2016). "Arsenic Pills and Lead Foundation: The History of Toxic Makeup". National Geographic. Archived from the original on November 5, 2018.

- Gupta, Aditya K; Nicol, Karyn (July–August 2004). "The Use of Sulfur in Dermatology". J Drugs Dermatol . 3 (4): 427–431. PMID 15303787.

- "Wonderful Medicine Free / Manhood Restored / The Great Hudyan". The Helena Weekly Independent. Helena, Montana, U.S. December 30, 1897. pp. 7–8. (and page 8)

- "Giving false information or omitting relevant information in the application". Victoria Legal Aid. 2014.

- Jolly, R (2011). "Marketing obesity? Junk food, advertising and kids". Parliament of Australia.

- "Dannon to Pay $45M to Settle Yogurt Lawsuit". ABC News. February 26, 2010.

- Jones, S. (2014). "Fat free and 100% natural: seven food labeling tricks exposed". The Conversation.

- Watson, E. (2014). "Heinz is latest target in new wave of false advertising lawsuits over 'all natural' claims and GMOs". Food Navigator-USA. com.

- "Nutella, After Suit, Drops Health Claims". ABC News. April 26, 2012.

- Sacks, Gary. "Big Food lobbying: tip of the iceberg exposed". TheConversation.com. Retrieved September 28, 2017.

- Lannin, S. (2016). "Consumer watchdog fines junk food giants over misleading 'healthy' kids food". ABC NEWS.

- "Understanding the claims on dietary supplement labels". cancer.org. Retrieved March 22, 2019.

- Faerber, Adrienne E.; Kreling, David H. (September 13, 2013). "Content Analysis of False and Misleading Claims in Television Advertising for Prescription and Nonprescription Drugs". Journal of General Internal Medicine. 29 (1): 110–118. doi:10.1007/s11606-013-2604-0. ISSN 0884-8734. PMC 3889958. PMID 24030427.

- Barry, Thomas E.; Tremblay, Roger L. (December 1, 1975). "Comparative Advertising: Perspectives and Issues". Journal of Advertising. 4 (4): 15–20. doi:10.1080/00913367.1975.10672603. ISSN 0091-3367.

- "15 U.S. Code § 1125 - False designations of origin, false descriptions, and dilution forbidden". LII / Legal Information Institute. Retrieved April 3, 2020.

- "False Ad Insights from Bud Light 'Corn Syrup' Case". Finnegan | Leading Intellectual Property Law Firm. Retrieved April 29, 2020.

- Calderwood, James (1998). "False & deceptive advertising". Ceramic Industry.

- Edman, Thomas. "LIES, DAMN LIES, AND MISLEADING ADVERTISING" (PDF). core.ac.uk.

- Hsieh Hsu Fang, Ching-Sheng Ya-Hui Wen-Chang (2010). "The Relationship Between Deceptive Claims and Ad Effect: The Moderating Role of Humorous Ads". International Journal of Business and Information.

- Vavreck, Lynn (November 19, 2007). "The Exaggerated Effects of Advertising on Turnout: The Dangers of Self-Reports". Quarterly Journal of Political Science. 2 (4): 325–343. doi:10.1561/100.00006005. ISSN 1554-0634.

- Chandran, Ravi (2004). "CONSUMER PROTECTION (FAIR TRADING) ACT". Singapore Journal of Legal Studies.

- Lysonski Duffy, Steven Michael F (1992). "The New Zealand Fair Trading ACt of 1986: Deceptive Advertising". The Journal of Consumer Affairs.

- Toncar Fetscherin, Mark Marc (2012). "A study of visual puffery in fragrance advertising". European Journal of Marketing. 46: 52–72. doi:10.1108/03090561211189239.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (June 22, 2010). "Light, Low, Mild or Similar Descriptors". Retrieved January 12, 2017.

- Barrionuevo, Alexei (October 4, 2005). "Egg Producers Relent on Industry Seal". The New York Times. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

- "Kellogg settles Rice Krispies false ad case". Retrieved April 1, 2016.

- "Suit Prompts Kellogg's to Drop "Natural" Labels on Kashi Products". NBC. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- "Fast Food Not As Pictured | Fast Food - Consumer Reports". www.consumerreports.org. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- "Don't Game Your Players with False Advertising". Law of the Level. February 15, 2017. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- "Bait And Switch Definition". Investopedia. April 11, 2014. Retrieved March 31, 2016.

- "What is Bait Advertising? - Definition from Techopedia". Techopedia.com. Retrieved September 28, 2017.

- "Bait Advertising - Department of the Attorney-General and Justice - NT Consumer Affairs". Consumeraffairs.nt.gov.au. January 6, 2016. Archived from the original on October 19, 2017. Retrieved March 31, 2016.

- "Bait advertising | Commerce Commission". Comcom.govt.nz. Retrieved March 31, 2016.

- "Misleading and Deceptive Conduct: Bait Advertising" (PDF). Journal.mtansw.com.au. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 24, 2016. Retrieved March 31, 2016.

- "Restatement (Second) of Contracts §33". Lexinter.net. Archived from the original on February 28, 2018. Retrieved June 2, 2012.

- Fredman, Catherine. "Fund Me or Fraud Me? Crowdfunding Scams Are on the Rise". Consumer Reports. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- Eighmey, J (2014). "My Experience as Deputy Assistant Director for National Advertising at the Federal Trade Commission". Journal of Public Policy & Marketing. 33 (2): 202–204. doi:10.1509/jppm.14.ftc.004.

- Drumwright, Minette E.; Murphy, Patrick E. (2009). "The Current State of Advertising Ethics: Industry and Academic Perspectives". Journal of Advertising. 38: 83–108. doi:10.2753/JOA0091-3367380106.

- 15 U.S.C. § 45

- "Truth In Advertising". Federal Trade Commission. August 5, 2013.

- Johar, Gita, "Intended and Unintended Effects of Corrective Advertising on Beliefs and Evaluations: An Exploratory Analysis", Journal of Consumer Psychology, 1996, 5(3), 209-230.

- Johar, Gita Venkataramani; Simmons, Carolyn J. (2000). "The Use of Concurrent Disclosures to Correct Invalid Inferences". Journal of Consumer Research. 26 (4): 307–322. doi:10.1086/209565.

- Richards, id; Policy Statement on Deception, 103 FTC Decisions 110 (1984), appendix to Cliffdale Associates; originally a letter from FTC Chairman James C. Miller to Rep. John D. Dingell (October 14, 1983). For the history of changing from deception to deceptiveness as the standard, see Preston, Ivan L., The Great American Blow-Up: Puffery in Advertising and Selling, University of Wisconsin Press, revised ed. (1996), at Ch. 8.

- "The Great American Fraud by Samuel Hopkins Adams, 1905". college.cengage.com. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- Millstein, Ira M. (1964). "The Federal Trade Commission and False Advertising". Columbia Law Review. 64 (3): 454–455. doi:10.2307/1120732. JSTOR 1120732.

- "ONY, Inc. v. Cornerstone Therapeutics, Inc., No. 12-2414 (2d Cir. 2013)". Justia Law.

- See e.g. N.Y. ISC. Law §§ 2401-2409.

- "Strengthen your claim: Informed consumers should keep an eye out for these issues". Radvocate.

- "Consumer Protection in the States: A 50-State Evaluation of Unfair and Deceptive Practices Laws" (PDF). National Consumer Law Center.

- "California Civil Code - CIV § 1770 - FindLaw". Findlaw.

- California Antitrust & Unfair Competition Law (Third), Volume 2: Unfair Competition (State Bar of California, 2003 Daniel Mogin & Danielle S. Fitzpatrick, eds.) at pg. 9.

- "Office of Trading. (2008). Consumer Protection from Unfair Trading. Department of Business Enterprise and Regulatory Reform. United Kingdom Government" (PDF). www.gov.uk. Retrieved September 28, 2017.

- "Advertising and selling guide". Australian Competition & Consumer Commission. October 24, 2016.

- "Fair Trading". ACC Government Access Canberra. October 25, 2016.

- "Fair Trading NSW". NSW government Fair Trading. October 25, 2016.

- "Fair Trading". Queensland Government. October 25, 2016.

- "Consumer and business services". Consumer and business services South Australia. October 25, 2016.

- "Consumer Affairs and Fair Trading". Tasmanian Government. October 25, 2016.

- "Consumer Affairs Victoria". Consumer Affairs Victoria. October 25, 2016.

- "Department of commerce". Government of Western Australia. October 25, 2016.

- "International Consumer Protection and Enforcement Network". ICPEN. October 24, 2016.

- "What is the Fair Trading Act ... | Commerce Commission". www.comcom.govt.nz. Retrieved April 1, 2016.

- "About us | Commerce Commission". www.comcom.govt.nz. Retrieved April 1, 2016.

- "Fair trading act". Consumer NZ. Retrieved April 1, 2016.

Further reading

- Breen, James O. (2014). "Personal Statement to Personal Physician:Bait and Switch?". Hastings Center Report. 44 (2): 25–7. doi:10.1002/hast.291. PMID 24634045.

- Freidman, D.A. (2009). Explaining "Bait-and-Switch" Regulation, 4 Wm. & Mary Bus. L. Rev. 575, http://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmblr/vol4/iss2/6

- Gardner, D. M. (1975). "Deception in Advertising: A Conceptual Approach". Journal of Marketing. 39 (1): 40–46. doi:10.2307/1250801. JSTOR 1250801.

- West, J. K. (2016). "Bait and Switch". Podiatry Management. 35 (3): 32.

- International Chamber of Commerce, Consolidated ICC Code of Advertising and Marketing Communication Practice, 2011.

- Schwarz, N.(2010). Feelings as information theory. University of Michigan. Retrieved from https://dornsife.usc.edu/assets/sites/780/docs/schwarz_feelings-as-information_7jan10.pdf

- Latour, K., & M (2009). Positive mood and susceptibility to false advertising. The Scholarly Commons. Cornell University School of Hotel Administration. Retrieved from http://scholarship.sha.cornell.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1312&context=articles

- Calvert, S. (2008). Children as consumers: Advertising and marketing. Retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/20171019224258/https://www.princeton.edu/futureofchildren/publications/docs/18_01_09.pdf

- Blackbird, J., Fox, T., & Tornetta, S. (2013). Color sells: how the psychology of color influences consumers. Archived https://web.archive.org/web/20160418195859/http://udel.edu/~rworley/e412/Psyc_of_color_final_paper.pdf

- Meat products with high levels of extenders and fillers. (n.d). Retrieved from []