Pennsylvania Turnpike

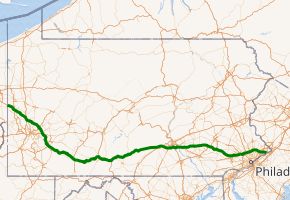

The Pennsylvania Turnpike is a toll highway operated by the Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission (PTC) in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania. A controlled-access highway, it runs for 360 miles (580 km) across the state. The turnpike begins at the Ohio state line in Lawrence County, where the road continues west as the Ohio Turnpike. It ends at the New Jersey border at the Delaware River–Turnpike Toll Bridge over the Delaware River in Bucks County, where the road continues east as the Pearl Harbor Memorial Extension of the New Jersey Turnpike.

| ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Pennsylvania Turnpike mainline highlighted in green | ||||||||||

| Route information | ||||||||||

| Maintained by PTC | ||||||||||

| Length | 360.09 mi[1] (579.51 km) | |||||||||

| Existed | October 1, 1940[2][3]–present | |||||||||

| History | Completed on May 23, 1956[4] | |||||||||

| Component highways |

| |||||||||

| Restrictions | No hazardous goods allowed in the Allegheny Mountain, Tuscarora Mountain, Kittatinny Mountain, and Blue Mountain tunnels | |||||||||

| Major junctions | ||||||||||

| West end | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| East end | ||||||||||

| Location | ||||||||||

| Counties | Lawrence, Beaver, Butler, Allegheny, Westmoreland, Somerset, Bedford, Fulton, Huntingdon, Franklin, Cumberland, York, Dauphin, Lebanon, Lancaster, Berks, Chester, Montgomery, Bucks | |||||||||

| Highway system | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Designated | 1990[5] | |||||||||

The highway runs east–west through the state, connecting the Pittsburgh, Harrisburg, and Philadelphia areas. It crosses the Appalachian Mountains in central Pennsylvania, passing through four tunnels. The turnpike is part of the Interstate Highway System; it is designated as part of Interstate 76 (I-76) between the Ohio border and Valley Forge, I-70 between New Stanton and Breezewood, I-276 between Valley Forge and Bristol Township, and I-95 from Bristol Township to the New Jersey border. The road uses an electronic toll collection system; tolls can be paid using E-ZPass or toll-by-plate (which uses automatic license plate recognition). Cash tolls were phased out between January 2016 and March 2020. Along the turnpike are 15 service plazas, providing food and fuel to travelers.

During the 1930s the Pennsylvania Turnpike was designed to improve automobile transportation across the mountains of Pennsylvania, using seven tunnels built for the abandoned South Pennsylvania Railroad in the 1880s. The road opened on October 1, 1940,[3] between Irwin and Carlisle. It was one of the earlier long-distance limited-access highways in the United States, and served as a precedent for additional limited-access toll roads and the Interstate Highway System.

Following World War II, the turnpike was extended east to Valley Forge in 1950 and west to the Ohio border in 1951. In 1954, the road was extended further east to the Delaware River. The mainline turnpike was finished in 1956 with the completion of the Delaware River Bridge. During the 1960s, an additional tube was bored at four of the two-lane tunnels, while the other three tunnels were bypassed; these improvements made the entire length of the highway four lanes wide. Improvements continue to be made to the road: rebuilding the original section to modern standards, widening portions of the turnpike to six lanes, and adding interchanges. Most recently in 2018, an ongoing interchange project saw the redesignation of the easternmost three miles (4.8 km) of the road from I-276 to I-95. Though still considered part of the turnpike mainline, it is no longer signed with turnpike markers.

Route description

The turnpike runs east–west across Pennsylvania, from the Ohio state line in Lawrence County to the New Jersey state line in Bucks County. It passes through the Pittsburgh, Harrisburg, and Philadelphia areas, along with farmland and woodland. The highway crosses the Appalachian Mountains, in the central part of the state, through four tunnels. The Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission, created in 1937 to construct, finance, operate, and maintain the road, controls the highway.[6] In 2015, the roadway had an annual average daily traffic count ranging from a high of 120,000 vehicles between Norristown and I-476 to a low of 12,000 vehicles between the Ohio border and the interchange with I-79 and U.S. Route 19 (US 19).[7] As part of the Interstate Highway System, the turnpike is part of the National Highway System,[8] a network of roads important to the country's economy, defense, and mobility.[9] The Pennsylvania Turnpike is designated as a Blue Star Memorial Highway honoring those who have served in the United States Armed Forces; the Garden Club Federation of Pennsylvania has placed Blue Star Memorial Highway markers at service plazas along the turnpike.[10][11]

In addition to the east–west mainline, the Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission also operates the Northeast Extension of the Pennsylvania Turnpike (I-476), the Beaver Valley Expressway (I-376), the Mon–Fayette Expressway (Pennsylvania Route 43 or PA 43), the Amos K. Hutchinson Bypass (PA 66), and the Southern Beltway (PA 576).[12]

Ohio to Irwin

The Pennsylvania Turnpike begins at the Ohio state line in Lawrence County, beyond which the highway continues west as the Ohio Turnpike. From the state line, the turnpike heads southeast as a four-lane freeway designated as I-76 through the rural area south of New Castle. A short distance from the Ohio border, the eastbound lanes come to the Gateway toll gantry, where tolls can be paid with E-ZPass or toll-by-plate at highway speeds. The highway then crosses into Beaver County, where it reaches its first interchange with I-376 (here, the part called Beaver Valley Expressway) in Big Beaver.[13][14][15]

After this interchange, the turnpike passes under Norfolk Southern's Koppel Secondary rail line before it reaches the exit for PA 18 in Homewood. Past PA 18, the highway crosses CSX's Pittsburgh Subdivision rail line, the Beaver River, and Norfolk Southern's Youngstown Line on the Beaver River Bridge.[6][13][14] The road then enters Butler County, where it comes to Cranberry Township.[15] Here, an interchange serves US 19 and I-79. The turnpike continues through a mix of rural land and suburban residential development north of Pittsburgh into Allegheny County.[14][15]

The road then approaches the Warrendale toll plaza, where toll ticketing begins, and continues southeast, passing over the P&W Subdivision rail line, which is owned by CSX and operated by the Buffalo and Pittsburgh Railroad. East of this point, the turnpike has an interchange with PA 8 in Hampton Township. The turnpike then comes to the Allegheny Valley exit in Harmar Township, which provides access to PA 28 via Freeport Road.[13][14] East of this interchange, the road heads south, with Canadian National's Bessemer Subdivision rail line parallel to the east of the road. The highway crosses Norfolk Southern's Conemaugh Line, the Allegheny River, and the Allegheny Valley Railroad's Allegheny Subdivision line on the six-lane Allegheny River Turnpike Bridge.[13][14][16]

After the Allegheny River crossing the turnpike returns to four lanes, passing through the Oakmont Country Club before coming to a bridge over Canadian National's Bessemer Subdivision line. From here, the railroad tracks run along the west side of the road before splitting further to the west. The highway heads southeast to Monroeville, an eastern suburb of Pittsburgh; an interchange with I-376/US 22 (Penn–Lincoln Parkway) provides access to Pittsburgh.[13][14] East of Monroeville, the turnpike continues through eastern Allegheny County before crossing into Westmoreland County.[14][15] Here, it heads south and passes over Norfolk Southern's Pittsburgh Line before it comes to the exit for US 30 in Irwin.[13][14]

Irwin to Carlisle

After the Irwin interchange, the Pennsylvania Turnpike widens to six lanes and heads into the rural area west of Greensburg. Curving southeast, it reaches New Stanton; an interchange provides access to I-70, US 119 and the southern terminus of PA 66 (the Amos K. Hutchinson Bypass). The road narrows back to four lanes at this interchange, and I-70 forms a concurrency with I-76 on the turnpike. After New Stanton, the road passes over the Southwest Pennsylvania Railroad's Radebaugh Subdivision line and winds southeast to the exit for PA 31/PA 711 in Donegal.[13][14] Continuing east past Donegal, the turnpike crosses Laurel Hill into Somerset County.[14][15]

In this county, the road continues southeast to Somerset and an interchange with PA 601 accessing US 219 and Johnstown before it passes over CSX's S&C Subdivision rail line. East of Somerset the highway reaches Allegheny Mountain,[13][14] going under it in the Allegheny Mountain Tunnel.[6][13][14] Exiting the tunnel, the turnpike winds down the mountain at a three-percent grade, which is the steepest grade on the turnpike,[14][17][18] and heads into Bedford County, passing through a valley.[15] At Bedford, an exit for US 220 Business (US 220 Bus.) provides access to US 220 and the southern terminus of I-99; this exit also serves Altoona to the north.[13][14]

East of Bedford the turnpike passes through the Bedford Narrows, a gap in Evitts Mountain. The turnpike, US 30, and the Raystown Branch of the Juniata River all pass through the 650-foot-wide (200 m) narrows.[14][17] The road winds through a valley south of the river, before traversing Clear Ridge Cut near Everett.[13][14][19] Further east, at Breezewood, I-70 leaves the turnpike.[13][14]

After Breezewood, I-76 continues along the turnpike, heading northeast across Rays Hill into Fulton County.[14][15] The turnpike continues east across Sideling Hill, before reaching an interchange with US 522 in Fort Littleton. After this interchange the highway parallels US 522 before curving east into Huntingdon County.[14][15] The turnpike goes under Tuscarora Mountain through the Tuscarora Mountain Tunnel, entering Franklin County.[6][14][15] It then curves northeast into a valley to the exit for PA 75 in Willow Hill.[13][14]

Again heading east, the road passes under Kittatinny Mountain through the Kittatinny Mountain Tunnel. Shortly after exiting the tunnel, the highway enters the Blue Mountain Tunnel under Blue Mountain.[6][13][14] Leaving that tunnel, the turnpike heads northeast along the base of Blue Mountain to an exit for PA 997.[13][14] East of this interchange the road enters Cumberland County, heading east through the Cumberland Valley on a stretch known as "the straightaway".[14][15][20] Further east, the turnpike reaches Carlisle and an interchange with US 11 providing access to I-81.[13][14]

Carlisle to Valley Forge

Approaching Harrisburg, the Pennsylvania Turnpike heads east through a mixture of rural land and suburban development, passing over Norfolk Southern's Shippensburg Secondary rail line. In Upper Allen Township, the highway reaches the US 15 interchange accessing Gettysburg to the south. The road continues east and passes over Norfolk Southern's Lurgan Branch rail line before it heads into York County, where it reaches the interchange with I-83 serving Harrisburg, its western suburbs and York to the south.[13][14][15] East of I-83, the turnpike widens to six lanes and crosses Norfolk Southern's Port Road Branch rail line, the Susquehanna River, and Amtrak's Keystone Corridor rail line on the Susquehanna River Bridge. Now in Dauphin County, the road bypasses Harrisburg to the south.[14][15][21]

In Lower Swatara Township the turnpike reaches an interchange with the southern end of I-283, serving Harrisburg and its eastern suburbs. Here, the road narrows back to four lanes through suburban development near Middletown. The roadway passes over the Middletown and Hummelstown Railroad and the Swatara Creek before it continues into rural areas.[13][14] The turnpike crosses a corner of Lebanon County before entering Lancaster County.[15]

In Lancaster County the highway passes through Pennsylvania Dutch Country[22] and reaches an interchange with PA 72 accessing Lebanon to the north and Lancaster to the south. Further east, the turnpike passes over an East Penn Railroad line in Denver before it reaches an interchange with US 222 and PA 272 which serves the cities of Reading and Lancaster. The route continues into Berks County and an interchange with I-176 (a freeway to Reading) and PA 10 in Morgantown.[13][14][15]

The turnpike then enters Chester County, running southeast[13][14][15] to an exit for PA 100 north of Downingtown, where it heads into the western suburbs of Philadelphia. Continuing east, it reaches an E-ZPass-only interchange with PA 29 near Malvern.[13][14] The highway crosses into Montgomery County and comes to the Valley Forge interchange in King of Prussia, where I-76 splits from the turnpike and heads southeast as the Schuylkill Expressway toward Philadelphia.[13][14][15]

Valley Forge to New Jersey

| |

|---|---|

| Location | Upper Merion Township – Bristol Township |

| Length | 29.78 mi[23] (47.93 km) |

| Existed | 1964–present |

Starting at the Valley Forge interchange the turnpike is designated as I-276 and becomes a six-lane road serving as a suburban commuter highway.[13][14][24] The road comes to a bridge over SEPTA's Norristown High Speed Line and runs parallel to Norfolk Southern's Dale Secondary rail line, which is located south of the road. The turnpike crosses Norfolk Southern's Harrisburg Line, the Schuylkill River, and SEPTA's Manayunk/Norristown Line on the Schuylkill River Bridge near Norristown. A short distance later, the road passes over the Schuylkill River Trail and Norfolk Southern's Morrisville Connecting Track on the Diamond Run Viaduct before the parallel Dale Secondary rail line heads further south from the road.[6][13][14] In Plymouth Meeting, an interchange with Germantown Pike provides access to Norristown before the roadway reaches the Mid-County Interchange. This interchange connects to I-476, which heads south as the Blue Route and north as the Northeast Extension of the turnpike; connecting the mainline turnpike to the Lehigh Valley and the Pocono Mountains.[13][14]

After the Mid-County Interchange, the main turnpike heads east through the northern suburbs of Philadelphia, passing over SEPTA's Lansdale/Doylestown Line before entering Fort Washington, where it has an interchange with PA 309. At this point, the road becomes parallel to Norfolk Southern's Morrisville Line, which is located a short distance to the south of the road. One mile (1.6 km) later, the turnpike has a westbound exit and entrance for Virginia Drive accessible only by E-ZPass tagholders. In Willow Grove the highway reaches the PA 611 exit before passing over SEPTA's Warminster Line.[13][14] The turnpike continues through more suburban areas, crossing into Bucks County and coming to a bridge over Norfolk Southern's Morrisville Line.[14][15] Farther east, the roadway passes over SEPTA's West Trenton Line. In Bensalem, the highway passes over CSX's Trenton Subdivision rail line before reaching an interchange with US 1, which provides access to Philadelphia.[13][14]

The highway narrows back to four lanes before another E-ZPass-only exit for PA 132, with an eastbound exit and entrance. A short distance later, the turnpike arrives at the east end of the ticket system at the Neshaminy Falls toll plaza. After passing through more suburbs, the road reaches a partial interchange with I-95 (passing under I-295 with no access), at which point I-276 ends and the Pennsylvania Turnpike becomes part of I-95. Here, signage indicates the westbound turnpike as a left exit from southbound I-95, using I-95 milepost exit number 40. This is the only place where continuing on the mainline turnpike is signed as an exit.[13][14]

After joining I-95, the remaining three miles (4.8 km) of road uses I-95's mileposts and is not directly signed as the Pennsylvania Turnpike, though it is still considered part of the mainline turnpike. Continuing east from the I-95 interchange, the turnpike reaches its final interchange, providing access to US 13 in Bristol. Following this, the road passes over an East Penn Railroad line before it comes to the westbound all-electronic Delaware River Bridge toll gantry.[13][14] After this, the highway crosses Amtrak's Northeast Corridor rail line and the Delaware River into New Jersey on the Delaware River–Turnpike Toll Bridge.[6][13][14] At this point, the Pennsylvania Turnpike ends, and I-95 continues north as the Pearl Harbor Memorial Extension of the New Jersey Turnpike, which connects to the mainline of the New Jersey Turnpike.[13][14][25]

Major bridges and tunnels

The Pennsylvania Turnpike incorporates several major bridges and tunnels along its route. Four tunnels cross central Pennsylvania's Appalachian Mountains. The 6,070-foot (1,850 m) Allegheny Mountain Tunnel passes under Allegheny Mountain in Somerset County. The Tuscarora Mountain Tunnel runs beneath Tuscarora Mountain (at the border of Huntingdon and Franklin Counties), and is 5,236 feet (1,596 m) long. The Kittatinny Mountain and Blue Mountain Tunnels are adjacent to each other in Franklin County and are 4,727 feet (1,441 m) and 4,339 feet (1,323 m) long, respectively.[6][13]

Five bridges carry the turnpike over major rivers in the state. The 1,545-foot-long (471 m) Beaver River Bridge crosses the Beaver River in Beaver County.[6][13] The highway crosses the Allegheny River in Allegheny County on the 2,350-foot-long (720 m) Allegheny River Turnpike Bridge,[13][16] and crosses the Susquehanna River between York and Dauphin Counties on the 5,910-foot-long (1,800 m) Susquehanna River Bridge.[13][21] In Montgomery County, the turnpike crosses the Schuylkill River on the 1,224-foot-long (373 m) Schuylkill River Bridge. At the New Jersey border in Bucks County, the highway is connected to the Pearl Harbor Memorial Extension of the New Jersey Turnpike by the 6,571-foot-long (2,003 m) Delaware River–Turnpike Toll Bridge over the Delaware River.[6][13]

Tolls

Until March 2020, the Pennsylvania Turnpike used the ticket system of tolling between the Warrendale and Neshaminy Falls toll plazas, as well as on the Northeast Extension to Wyoming Valley.[26] When entering the turnpike, motorists received a ticket listing the toll for each exit; the ticket was surrendered when exiting, and the applicable toll was paid. If the ticket was lost, motorists were charged the maximum toll for that exit.[27] Cash, credit cards, and E-ZPass were accepted at traditional toll plazas. An eastbound mainline toll gantry is located at Gateway near the Ohio border and a westbound mainline toll gantry is located at the Delaware River Bridge near the New Jersey border, both charging a flat toll using toll-by-plate (which uses automatic license plate recognition to take a photo of the vehicle's license plate and mail a bill to the vehicle owner) or E-ZPass at highway speeds.[26][28] There is no toll between Gateway and Warrendale and between Neshaminy Falls and the Delaware River Bridge. The PA 29 interchange and the westbound Virginia Drive and eastbound Street Road interchanges only accept E-ZPass.[26]

As of 2020 it costs a passenger vehicle $53.50 to travel the length of the mainline turnpike between Warrendale and Neshaminy Falls using cash, and $38.40 using E-ZPass; the eastbound Gateway toll costs $12.20 with toll-by-plate and $5.90 with E-ZPass for passenger vehicles while the westbound Delaware River Bridge toll gantry costs $7.70 using toll-by-plate and $5.70 using E-ZPass.[26] Since 2009, the turnpike has raised tolls once a year, starting on January 1, to provide funding for increasing annual payments to PennDOT, as mandated by Act 44.[29] The turnpike commission paid PennDOT $450 million annually, of which $200 million went to non-turnpike highway projects across the state and $250 million went to funding mass transit. As part of Act 89 signed in 2013, the annual payments to PennDOT will end after 2022 (35 years earlier than the original proposal under Act 44), but it is not known if the annual toll increases will continue after 2022. Act 89 has also redirected the entire $450 million annual payments to PennDOT towards funding mass transit.[30] With the annual rise in tolls, traffic has been shifting from the turnpike to local roads.[31]

The turnpike commission has eliminated manned toll booths in favor of all-electronic tolls.[32][33] McCormick Taylor and Wilbur Smith Associates have been hired to conduct a feasibility study on converting the road to all-electronic tolls.[34] On March 6, 2012, the turnpike commission announced that it was implementing this plan.[35] The turnpike commission will save $65 million annually on labor costs by eliminating toll collectors.[36] On January 3, 2016, all-electronic tolling was introduced in the westbound direction at the Delaware River Bridge mainline toll plaza, while the eastern terminus of the ticket system was moved from the Delaware River Bridge to Neshaminy Falls.[37] On October 27, 2019, all-electronic tolling was implemented at the eastbound Gateway mainline toll plaza.[38] All-electronic tolling was originally scheduled to be implemented on the entire length of the Pennsylvania Turnpike in the later part of 2021.[39] However, in March 2020 the turnpike implemented all-electronic tolling along its entire length as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. The all-electronic tolling was intended to be temporary, but in June 2020 the move to all-electronic tolling became permanent, with toll collectors laid off.[40] The all-electronic tolling system on the turnpike will initially use toll booths at exits until mainline toll gantries between interchanges are constructed. Mainline toll gantries are planned to begin operation in eastern Pennsylvania by 2022, central Pennsylvania by 2024, and western Pennsylvania by 2026.[39]

Act 44 toll increases

The turnpike commission raised tolls by 25 percent on January 4, 2009 to provide funds to the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation for road and mass-transit projects, as mandated by Act 44.[29][41] This toll hike brought the rate to travel the turnpike to 7.4 cents per mile (4.6 ¢/km), or 9 ¢/mi (5.6 ¢/km) in 2018.[42][43] At this point, an annual toll increase was planned.[41]

A three-percent toll increase went into effect January 3, 2010, bringing the rate to 7.7 cents per mile (4.8 ¢/km) or 9 ¢/mi (5.6 ¢/km) in 2018.[42][44][45] The cash toll increased 10 percent on January 2, 2011, and E-ZPass tolls increased three percent.[46] The new toll rate was 8.5 cents per mile (5.3 ¢/km) or 9 ¢/mi (5.6 ¢/km) in 2018 using cash, and 7.9 cents per mile (4.9 ¢/km) or 9 ¢/mi (5.6 ¢/km) in 2018 using E-ZPass.[42][47] As part of this toll hike the turnpike commission initially planned to omit the toll amount from new tickets, and Pennsylvania Auditor Jack Wagner wondered if the commission was trying to hide the increase.[46] The commission later decided to include the tolls on new tickets.[34]

Cash tolls increased 10 percent on January 1, 2012, while E-ZPass tolls were unchanged from the previous year.[48] With this increase, the cash toll rate increased to 9.3 cents per mile (5.8 ¢/km) or 10 ¢/mi (6.2 ¢/km) in 2018.[49] Tolls for both cash and E-ZPass customers increased in January of each of the next eight years.[50]

Services

Emergency assistance and information

The turnpike used to have a callbox every mile for its entire length.[51] Callboxes were first installed between New Stanton and New Baltimore in December 1988, and in 1989, callboxes were extended along the length of the highway.[52] In September 2017, the turnpike commission began removing the callboxes due to increased mobile phone usage making the callboxes obsolete.[53] Motorists may also dial *11 on mobile phones. First-responder service is available to all turnpike users via the State Farm Safety Patrol program. The free program checks for disabled motorists, debris and accidents along the road and provides assistance 24 hours daily year-round. Each patrol vehicle covers a 20-to-25-mile (32 to 40 km) stretch of the turnpike.[54] Towing service is available from authorized service stations near the highway,[55] and Pennsylvania State Police Troop T patrols the turnpike. The troop's headquarters is in Highspire; its turnpike substations are grouped into three sections: the western section has substations in Gibsonia, Somerset, and New Stanton; the central section's substations are in Bowmansville, Everett and Newville, and the eastern section's substation is in King of Prussia.[56]

The Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission broadcasts road, traffic, and weather conditions over highway advisory radio transmitters at each exit on 1640 kHz AM, with a range of approximately two miles (3.2 km).[57] Motorists can also receive alerts and information via the internet, mobile phone, a hotline and message boards at service plazas through the Turnpike Roadway Information Program (TRIP).[58]

Service plazas

The Pennsylvania Turnpike has 15 service plazas on the main highway throughout the state, as well as 2 on the northeastern extension. Each plaza has fast food restaurants, a Sunoco gas station, and a 7-Eleven convenience store. Other amenities include ATMs, free cell phone charging, picnic areas, restrooms, tourist information, Travel Board information centers, and Wi-Fi. The King of Prussia plaza has a welcome center, and the New Stanton and Sideling Hill plazas feature seasonal farmers' markets. A few plazas offer E85 while New Stanton offers compressed natural gas; all of them offer conventional gasoline and diesel fuel. Select service plazas have electric vehicle charging stations.[59] The Sunoco and 7-Eleven locations as well as the Subway at North Midway are operated by Energy Transfer Partners (who bought Pennsylvania-based Sunoco in 2012) while the remaining restaurants and general upkeep of the service plazas are operated by HMSHost.[60]

Throughout the Turnpike's history, various plazas have been added or eliminated. Two of the original plazas (at Laurel Hill and New Baltimore) were closed in the 1950s while the bypassing of what is now the Abandoned Turnpike led to the closure of the Cove Valley Plaza and opening of the Sideling Hill plaza, which serves both westbound and eastbound traffic.[61] In 1980, the plazas at Denver, Pleasant Valley and Mechanicsburg were sold to outside bidders and in 1983 the Path Valley plaza closed due to declining business, as it was only 15 miles (24 km) east of the dual-access Sideling Hill plaza.[62] Throughout the decade, the former Howard Johnson restaurants were converted to a variety of fast food outlets and sit-down restaurants at some locations.[63] In 1990 the Brandywine (now Peter J. Camiel) plaza was demolished and reconstructed,[64] and in 2002 the Butler plaza closed to make room for the Warrendale Toll Plaza.[65]

Starting in 2006, the Turnpike Commission and HMSHost worked to rebuild the service plazas starting with Oakmont, which closed in 2006 and reopened in 2007. This was followed by the reconstruction of the North Somerset and Sideling Hill plazas (2007–2008), New Stanton (2008–2009), King of Prussia (2009–2010), Lawn and Bowmansville (2010–2011), South Somerset, Blue Mountain and Plainfield (2011–2012), South Midway and Highspire (2012–2013), Peter J. Camiel (2013–2014), and Valley Forge and North Midway (2014–2015).[66] During this process, four plazas were eliminated altogether: the Hempfield and South Neshaminy plazas were demolished in 2007 for additional lanes and a new slip ramp, respectively,[67][68] the Zelienople plaza closed in 2008 due to a lack of business since it was located on the free stretch of the turnpike from Ohio to Warrendale,[69] and the North Neshaminy plaza shut down in 2010 for an upcoming construction project.[70]

The Art Sparks program was launched in 2017 as a partnership between the turnpike commission and the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts to install public art created by local students in the Arts in Education residency program in service plazas along the turnpike over the next five years. The public art consists of a mural reflecting the area where the service plaza is located. The first Art Sparks mural debuted at the Lawn service plaza in May 2017.[71][72]

In April 2019, the Sunoco/A-Plus locations began to be converted to 7-Eleven locations, as part of a larger deal that saw 7-Eleven take over Sunoco's company-owned convenience stores along the East Coast and Texas; Sunoco will continue to supply fuel to the locations.[73][74]

History

The Pennsylvania Turnpike was planned in the 1930s to improve transportation across the Appalachian Mountains of central Pennsylvania. It used seven tunnels bored for the abandoned South Pennsylvania Railroad project during the 1880s.[75] The highway opened on October 1, 1940 between Irwin and Carlisle as the first long-distance controlled-access highway in the United States.[76] Following its completion, other toll roads and the Interstate Highway System were built.[77] The highway was extended east to Valley Forge in 1950, and west to the Ohio border in 1951.[78][79] It was completed at the New Jersey border (the Delaware River) in 1954; the Delaware River Bridge opened two years later.[80][4] During the 1960s, the entire highway was expanded to four lanes by adding a second tube at four of the tunnels and bypassing the other three.[81] Other improvements have been made, including the addition of interchanges, the widening of portions of the highway to six lanes and the reconstruction of the original section. A partial interchange with I-95 opened in September 2018, and will be expanded to a full interchange in the future.[82]

Planning

Before the turnpike, there were other forms of transportation across the Appalachians. Native Americans traveled across the mountains along wilderness trails; later, European settlers followed wagon roads to cross the state.[83] The Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike opened between Lancaster and Philadelphia in 1794, the first successful turnpike in the United States. The road was paved with logs, an improvement on the dirt Native American trails.[84] In 1834, the Main Line of Public Works opened as a system of canals, railroads and cable railways across Pennsylvania to compete with the Erie Canal in New York.[85]

The Pennsylvania Railroad was completed between Pittsburgh and Philadelphia in 1854.[86] During the 1880s, the South Pennsylvania Railroad was proposed to compete with the Pennsylvania. It received the backing of William Henry Vanderbilt, head of the New York Central Railroad (the Pennsylvania's chief rival). Andrew Carnegie also provided financial support, since he was unhappy with rates charged by the Pennsylvania Railroad.[87] Construction began on the rival line in 1883, but stopped when the railroads reached an agreement in 1885.[88][89] After construction halted, the only vestiges of the South Pennsylvania were nine tunnels, some roadbed, and piers for a bridge over the Susquehanna River in Harrisburg.[89]

During the early 20th century, the automobile gradually became the primary form of transportation.[75] Motorists crossing the Pennsylvania mountains during the 1930s were limited to hilly, winding roads such as the Lincoln Highway (US 30) or the William Penn Highway (US 22), which had grades exceeding nine percent.[18][90] Due to their sharp curves and steep grades, the roads were dangerous and caused many fatal accidents from skids.[88]

As a result of the challenge of crossing the Pennsylvania mountains by automobile, William Sutherland of the Pennsylvania Motor Truck Association and Victor Lecoq of the Pennsylvania State Planning Commission proposed a toll highway in 1934.[75][91] This highway would be a four-lane limited-access road modeled after the German autobahns and Connecticut's Merritt Parkway.[88][92][93] The turnpike could also serve as a defense road,[94] using the abandoned tunnels of the South Pennsylvania Railroad project.[75]

In 1935 Sutherland and Lecoq introduced their turnpike idea to state legislator Cliff Patterson, who proposed a feasibility study on April 23, 1935. The proposal passed, and the Works Progress Administration (WPA) explored the possibility of building the road. Its study estimated a cost of between $60 and $70 million (between $881 million and $1.03 billion in 2018 dollars[95]) to build the turnpike. Patterson introduced Bill 211 to the legislature, calling for the establishment of the Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission. The bill was signed into law by Governor George Howard Earle III on May 21, 1937[75] and on June 4, the first commissioners were appointed.[96] The highway was planned to run from US 30 in Irwin (east of Pittsburgh) east to US 11 in Middlesex (west of Harrisburg), a length of about 162 miles (261 km). It would pass through nine tunnels along the way.[97]

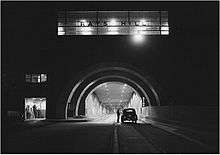

The road would have four lanes, with a median and no grade steeper than three percent. Access to the highway would be controlled by entrance and exit ramps.[97] There would be no at-grade intersections, driveways, traffic lights, crosswalks or at-grade railroad crossings.[98] Curves would be wide, and road signage large. The right-of-way for the turnpike would be 200 feet (61 m); the road would be 24 feet (7.3 m) wide, with 10-foot (3.0 m) shoulders and a 10-foot (3.0 m) median. Through the tunnels the road would have two lanes, a 14-foot (4.3 m) clearance and a 23-foot-wide (7.0 m) roadway.[97] The turnpike's design would be uniform for its entire length.[98]

In February 1938, the commission began investigating proposals for $55 million in bonds to be issued for construction of the turnpike.[99] A month later, Van Ingen and Company purchased $60 million (about $858 million in 2018 dollars[95]) in bonds they would offer to the public.[100] President Franklin D. Roosevelt approved a $24 million (about $343 million in 2018 dollars[95]) grant from the WPA in April 1938 for construction of the road; the commonwealth also contributed $29 million towards the project.[101] The WPA grant received final approval,[102] but plans were still made to sell bonds; the first issue was planned for about $20 million (about $286 million in 2018 dollars[95]). The reduced bond issue was due to the grant from the WPA.[103]

In June, the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) announced they would lend the commission sufficient funds to build the road.[104] The RFC loan totaled $32 million (about $458 million in 2018 dollars[95]), with a $26 million (about $372 million in 2018 dollars[95]) grant from the Public Works Administration (PWA), providing $58 million for the turnpike's construction; highway tolls would repay the RFC.[105] In October 1938, the turnpike commission agreed with the RFC and PWA that the RFC would purchase $35 million in bonds, in addition to the PWA grant.[106] That month, a banking syndicate purchased the entire bond amount from the RFC.[107] The previous month, a proposed railroad from Pittsburgh to Harrisburg using the former South Pennsylvania Railroad right-of-way that had been designated for the turnpike was turned down.[108]

Design

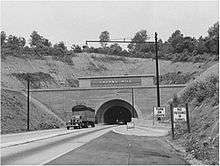

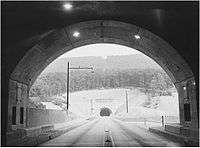

In building the turnpike, boring the former railroad tunnels was completed. Since the Allegheny Mountain Tunnel bore was in poor condition, a new bore was drilled 85 feet (26 m) to the south.[109] The commission considered bypassing the Rays Hill and Sideling Hill Tunnels, but the cost of a bypass was considered too high.[81] Crews used steam shovels to widen the tunnels' portals,[109] and temporary railroad tracks transported construction equipment in and out.[110] Concrete was used in lining the tunnel portals.[111] The tunnels include ventilation ducts, drainage structures, sidewalks, lighting, telephone and signal systems.[112] Lighting was installed along the roadway approaching the tunnel portals.[113]

The tunnels bored through the seven mountains totaled 4.5 miles (7.2 km). The tunnels were Laurel Hill Tunnel, Allegheny Mountain Tunnel, Rays Hill Tunnel, Sideling Hill Tunnel, Tuscarora Mountain Tunnel, Kittatinny Mountain Tunnel, and Blue Mountain Tunnel, and the road became known as the "tunnel highway".[114]

Many bridge designs were used for roads over the highway, including the concrete arch bridge, the through plate girder bridge, and the concrete T-beam bridge.[115][116][117] Bridges used to carry the turnpike over other roads and streams included a concrete arch viaduct in New Stanton.[118] At 600 feet (180 m), the New Stanton viaduct was the longest bridge along the original section of the turnpike.[119] Other turnpike bridges included plate girder bridges like the bridge over Dunnings Creek in the Bedford Narrows. Smaller concrete T-beam bridges were also built[120][121] A total of 307 bridges were constructed along the original section of the turnpike.[119]

Eleven interchanges were built along the turnpike, most of which were trumpet interchanges in which all ramps merge at the toll booths;[122][123] only the New Stanton, Carlisle, and Middlesex interchanges did not follow this design.[122] Lighting was installed approaching interchanges, along with acceleration and deceleration lanes.[113] The road also featured guardrails, consisting of steel panels attached to I-beams.[124] Large exit signs were used, and road signs had cat's-eye reflectors to increase visibility at night.[124][125] Billboards were prohibited.[126] In September 1940, the Pennsylvania Public Utility Commission ruled that trucks and buses would be allowed to use the highway.[127]

Since the first section of the highway was built through a rural part of the state, food and gasoline was not easily available to motorists. Because of this, the commission decided to provide service plazas at 30-mile (48 km) intervals. The plazas would be constructed of native fieldstone, resembling Colonial-era architecture.[128][129] In 1940, Standard Oil of Pennsylvania was awarded a contract for ten Esso service stations along the turnpike.[130] Eight of the service plazas would consist of service stations and a restaurant, while the plazas at the halfway point (in Bedford) would be larger.[129][130] The South Midway service plaza (the largest) contained a dining room, lunch counter, lounge, and lodging for truckers; a tunnel connected it to the smaller North Midway plaza.[129][131] The remaining service plazas were smaller, with a lunch counter. Food service at the plazas was provided by Howard Johnson's. After World War II, the food facilities were enlarged;[131] service stations sold gasoline, repaired cars and provided towing service.[132]

Construction of first section

Before the first-section groundbreaking, in 1937 the turnpike commission sent workers to assess the former railroad tunnels. In September of that year, a contract was awarded to drain water from the tunnels.[133] After this, workers cleared rock slides and vegetation from the tunnel portals before evaluating the nine tunnels' condition.[134][135] It was decided that six of the nine former South Pennsylvania Railroad tunnels could be used for the roadway. The Allegheny Mountain Tunnel was in too poor a condition for use, and the Quemahoning and Negro Mountain tunnels would be bypassed with rock cuts through the mountains.[135] The Quemahoning Tunnel had been completed and used by the Pittsburgh, Westmoreland and Somerset Railroad.[136]

The Pennsylvania Turnpike groundbreaking was held on October 27, 1938, near Carlisle; Commission Chairman Walter A. Jones thrust the first shovel into the earth.[137] Turnpike construction was on a tight schedule, because completion of the road was originally planned by May 1, 1940. After the groundbreaking, contracts for finishing the former South Pennsylvania Railroad tunnels, grading the turnpike's right-of-way, constructing bridges, and paving were awarded.[18] By July 1939, the entire length of the turnpike was under contract.[98]

The first work to begin on the road was grading its right-of-way, which involved a great deal of earthwork due to the mountainous terrain.[137] Building the highway required the acquisition of homes, farms, and a coal mine by eminent domain.[98] A tunnel was originally planned across Clear Ridge near Everett, but the turnpike commission decided to build a cut into the ridge.[19] Building the cut involved bulldozers excavating the mountain and explosives blasting the rock.[138] Concrete culverts were built to carry streams and roads under the highway in the valley floor.[139] The Clear Ridge cut was 153 feet (47 m) deep (the deepest highway cut at the time), and was known as "Little Panama" after the Panama Canal.[119] West of Clear Ridge, cuts and fills were built for the turnpike to pass along the southern edge of Earlston.[140]

Considerable work was also involved in building the roadway up the three-percent grade at the east end of Allegheny Mountain, the steepest grade the turnpike traversed.[141] The base of Evitts Mountain was blasted to carry the turnpike across Bedford Narrows along with US 30, the Raystown Branch of the Juniata River, and a Pennsylvania Railroad branch line.[17] In New Baltimore, the turnpike commission had to purchase land from St. John's Church (which contained a cemetery); as part of the agreement, stairways were built on either side of the turnpike to provide access to the church.[142]

Paving began on August 31, 1939.[98] The roadway would have a concrete surface, and concrete was poured directly onto the earth with no gravel roadbed.[143] Concrete batch plants were set up along the road to aid in paving.[144] Interchange ramps were paved with asphalt.[121] The paving operations led to a delay in the projected opening of the highway; by October 1939 the completion date was pushed back from May 1 to June 29, 1940, since paving could not be done during the winter. The commission rushed the paving, attempting to increase the distance paved from 1 to 5 miles (1.6 to 8.0 km) a day.[112]

Completion was postponed to July 4, before being again postponed to late summer 1940 when rain delayed paving operations.[145] Paving concluded by the end of the summer, and on September 30, the turnpike commission announced that the road would open on October 1, 1940.[18][146][147] Since the turnpike was opened on short notice, no ribbon-cutting ceremony was held.[147]

On August 26, 1940, a preview of the highway was organized by commission chairman Jones. It began the previous night with a banquet at The Hotel Hershey and proceeded west along the turnpike, stopping at the Clear Ridge cut before lunch at the Midway service plaza. The preview ended with dinner and entertainment at the Duquesne Club in Pittsburgh.[146][148] That month, a military motorcade traveled portions of the turnpike.[149]

The roadway took 770,000 short tons (700 kt) of sand, 1,200,000 short tons (1,100 kt) of stone, 50,000 short tons (45 kt) of steel and more than 300,000 short tons (270 kt) of cement to complete.[114] It was built at a cost of $370,000 per mile ($230,000/km).[150] A total of 18,000 men worked on the turnpike; 19 died during its construction.[151]

When the highway was under construction in 1939, its proposed toll was $1.50 (about $27.00 in 2018 dollars[42]) for a one-way car trip; a round trip would cost $2.00 (about $36.00 in 2018). Trucks would pay $10.00 (about $181.00 in 2018) one way. Varying tolls would be charged for motorists who did not travel the length of the turnpike.[112] Upon its opening in 1940, automobile tolls were set at $1.50 (about $27.00 in 2018) one way and $2.25 (about $40.00 in 2018) round trip. The tolls were to be used to pay off bonds to build the road, and were to be removed when the bonds were paid.[113] However, tolls continue to be charged to finance improvements to the turnpike system.[152] The toll rate was about 1 cent per mile (0.62 ¢/km)—18 ¢/mi (11 ¢/km) in 2018[42]—when the turnpike opened. The ticket system was used to pay for tolls.[153] This toll rate remained the same for the turnpike's first 25 years; other toll roads (such as the New York State Thruway and the Ohio, Connecticut and Massachusetts Turnpikes) had a higher rate.[154]

Opening of first section

The Pennsylvania Turnpike opened at midnight on October 1, 1940, between Irwin and Carlisle; the day before the opening, motorists lined up at the Irwin and Carlisle interchanges.[76] Homer D. Romberger, a feed and tallow driver from Carlisle, became the first motorist to enter the turnpike at Carlisle, and Carl A. Boe of McKeesport became the first motorist to enter at Irwin.[155] Boe was flagged down by Frank Lorey and Dick Gangle, the first hitchhikers along the turnpike.[156] On October 6 (the first Sunday after the turnpike's opening) traffic was heavy, with congestion at toll plazas, tunnels and service plazas.[157]

During its first 15 days of operation, the road saw over 150,000 vehicles.[158] By the end of its first year the road earned $3 million in revenue from 5 million motorists, exceeding the $2.67 million needed for operation and bond payments.[159][160] With the onset of World War II, revenue declined due to tire and gas rationing;[161] after the war, traffic again increased.[162]

When it opened, the turnpike became the first long-distance limited-access road in the United States.[77] It provided a direct link between the Mid-Atlantic and Midwestern states, and cut travel time between Pittsburgh and Harrisburg from nearly six to about two-and-a-half hours.[113][163] The road was given the nicknames "dream highway" and "the World's Greatest Highway" by the turnpike commission,[2][153] and was also known as "the Granddaddy of the Pikes."[164] Postcards and other souvenirs promoted the original stretch's seven tunnels through the Appalachians.[165]

The highway was considered a yardstick by which limited-access highway construction would be measured.[166] Commission chairman Jones called for more limited-access roads to be built across the country for defense purposes,[159] and the turnpike was a model for a proposed national network of highways planned during World War II.[167] The Pennsylvania Turnpike led to the construction of other toll roads, such as the New Jersey Turnpike and (eventually) the Interstate Highway System.[77] It has been designated a National Civil Engineering Landmark by the American Society of Civil Engineers.[168]

The concrete highway pavement began to fail several years after the road opened due to excessive transverse-joint spacing and the lack of gravel between earth and concrete. As a result, in 1954 an eight-year project began to repave the turnpike with a 3-inch (7.6 cm) layer of asphalt between Irwin and Carlisle.[169][77]

Extensions

Before the first section of the Pennsylvania Turnpike opened, the commission considered extending it east to Philadelphia, primarily for defense purposes. In 1939, the state legislature passed a bill allowing for an extension of the road to Philadelphia, which was signed into law by Governor Arthur H. James in 1940 as Act 11.[93][170] The extension was projected to cost between $50 and $60 million in 1941.[170] Funding for the Philadelphia extension was in place in 1948.[171] In July 1948, the turnpike commission offered $134 million in bonds to pay for the extension, which was projected to cost $87 million.[172] The Philadelphia extension was to run from Carlisle east to US 202 in King of Prussia.[78][173] From there, the extension would connect to a state-maintained freeway that would continue to Center City Philadelphia.[174] Groundbreaking for the Philadelphia extension took place on September 28, 1948 in York County. Governor James H. Duff and commission chairman Thomas J. Evans attended the ceremony.[175]

The extension would look similar to the original section of the turnpike, but would use air-entrained concrete poured onto stone.[78][176] Transverse joints on the pavement were spaced at 46-foot (14 m) intervals rather than the 77-foot (23 m) ones on the original portion.[78] Because it traversed through less mountainous terrain, the extension did not require as much earthwork as the original section.[177] It required the construction of large bridges, including those that cross the Susquehanna River and the Swatara Creek.[178][179] To save money, the Susquehanna River Bridge was constructed with a 4-foot (1.2 m)-raised concrete median and no shoulders.[178] This extension of the turnpike would use the same style of overpasses as the original section; the steel deck bridge was also introduced.[180] With the construction of the Philadelphia extension, the Carlisle interchange was closed and the Middlesex interchange with US 11 was realigned to allow for the new extension; it was renamed to the Carlisle interchange.[177]

The extension's completion was delayed by weather and a cement workers' strike; it was to have been finished by October 1, 1950—the tenth anniversary of the opening of the first section.[181] On October 23, 1950, the Philadelphia extension was previewed in a ceremony led by Governor Duff.[182] The extension opened to traffic on November 20, 1950; the governor and chairman Evans cut the ribbon at the Valley Forge mainline toll plaza to the west of King of Prussia.[78][183]

In 1941, Governor James suggested building a western extension to Ohio.[170] That June, Act 54 was signed into law to build the extension.[184] In 1949, the turnpike commission began enquiring into funding for this road, which would run from Irwin to the Ohio border near Youngstown, bypassing Pittsburgh to the north.[185] That September, $77 million in bonds were sold to finance construction of the western extension.[186] Groundbreaking for the extension took place on October 24, 1949.[187] It was scheduled to take place at the Brush Creek viaduct in Irwin with Governor Duff in attendance.[188]

Like the Philadelphia extension, the western extension required the building of long bridges, including those that cross the Beaver River and the Allegheny River.[189] The overpasses along the road consisted of steel girder bridges and through plate girder bridges.[190] Unlike the other segments, the concrete arch bridge was not used for overpasses, although it was used to carry the turnpike over other roads.[191] On August 7, 1951, the roadway opened between the Irwin and Pittsburgh interchanges.[192] Ohio Governor Frank Lausche led a dedication ceremony on November 26, 1951.[193] The extension opened to the Gateway toll plaza near the Ohio border on December 26, 1951.[79][194] At the time, the highway ended in a cornfield. Traffic followed a temporary ramp onto local rural roads until the connecting Ohio Turnpike could be built.[79][193] On December 1, 1954, the Ohio Turnpike opened.[195]

In 1951, plans to extend the turnpike east to New Jersey at the Delaware River to connect with the New Jersey Turnpike were made.[196] The construction of the Delaware River extension was approved by Governor John S. Fine in May of that year.[197] A route for the extension, which would bypass Philadelphia to the north, was announced in 1952. It would cross the Delaware River on a bridge north of Bristol near Edgely, where it would connect to a branch of the New Jersey Turnpike.[198] That September, the turnpike commission announced $65 million in bonds would be issued to finance the project.[199] Work on the Delaware River extension began on November 20, 1952; Governor Fine dug the first shovel into the earth at the groundbreaking ceremony.[200] As a result of building the extension, the Valley Forge mainline toll plaza was located farther east at the connection to the Schuylkill Expressway, and would then become the Valley Forge interchange toll plaza.[201] The Delaware River extension included a bridge over the Schuylkill River that was built to the same standards as the Susquehanna River Bridge.[202] The construction of the Delaware River bridge required an amendment to the Pennsylvania Constitution, which barred the state from forming compacts with other states. On August 23, 1954, the Delaware River Extension opened between King of Prussia and US 611 in Willow Grove.[203] The remainder of the road to the Delaware River opened on November 17, 1954.[80]

In April 1954, $233 million in bonds were issued to finance the building of the Delaware River Bridge and the Northeast Extension.[204] Groundbreaking for the Delaware River Bridge connecting the Pennsylvania Turnpike to the New Jersey Turnpike took place on June 26, 1954 in Florence, New Jersey.[80] The steel arch bridge, which opened to traffic on May 23, 1956, was funded jointly by the Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission and the New Jersey Turnpike Authority.[4][205] Pennsylvania Governor George M. Leader and New Jersey Governor Robert B. Meyner were present at the opening ceremony.[206] A mainline toll barrier was built to the west of the bridge, marking the eastern end of the ticket system.[207] This bridge was originally six lanes wide. It contained no median, but one was later installed and the bridge was reduced to four lanes.[4]

With the construction of the extensions and connecting turnpikes, the highway was envisioned to be a part of a system of toll roads stretching from Maine to Chicago.[208] When the Delaware River Bridge was completed in 1956, a motorist could drive from New York City to Indiana on limited-access toll roads.[207] By 1957, it was possible to drive from New York City to Chicago without encountering a traffic signal.[209]

On the turnpike extensions, the service plazas were less frequent, larger, and further from the road.[180] Gulf Oil operated service stations on the extensions, and Howard Johnson's provided food service in sit-down restaurants.[210][211]

Route numbers

| |

|---|---|

| Location | North Beaver Township – Upper Merion Township |

| Existed | 1958–1964 |

| |

|---|---|

| Location | Upper Merion Township – Bristol Township |

| Length | 32.65 mi[23] (52.55 km) |

| Existed | 1958–1964 |

In August 1957, the Bureau of Public Roads added the roadway to the Interstate Highway System upon the recommendations of various state highway departments to include toll roads in the system.[212] I-80 was planned to run along the turnpike from the Ohio border to Harrisburg while I-80S would continue eastward toward Philadelphia. I-70 was also planned to follow the turnpike between Pittsburgh and Breezewood.[213] At a meeting of the Route Numbering Subcommittee on the U.S. Numbered System on June 26, 1958, it was decided to move the I-80 designation to an alignment further north while the highway between the Ohio border and the Philadelphia area would become I-80S. I-70 was still designated on the turnpike between Pittsburgh and Breezewood. Between King of Prussia and Bristol, the turnpike was designated I-280.[214][215]

In April 1963, the state of Pennsylvania proposed renumbering I-80S to I-76 and I-280 to I-276 because the spurs of I-80S did not connect to I-80 in northern Pennsylvania. The renumbering was approved by the Federal Highway Administration on February 26, 1964. With this renumbering, the turnpike would carry I-80S between the Ohio border and Pittsburgh, I-76 between Pittsburgh and King of Prussia, I-70 between New Stanton and Breezewood, and I-276 between King of Prussia and Bristol. In 1971, the state of Ohio wanted to eliminate I-80S, replacing it with a realigned I-76. The state of Pennsylvania disagreed with the change and recommended that I-80S become I-376 instead. The Pennsylvania government later changed its mind and supported Ohio's plan to renumber I-80S as I-76. In December of that year, the change was approved by the American Association of State Highway Officials. As a result, I-76 would follow the turnpike between the Ohio border and King of Prussia.[215] This change took effect on October 2, 1972.[216] With the completion of ramps connecting I-95 and the Pennsylvania Turnpike near Bristol on September 22, 2018, the portion of the turnpike between the new interchange and the New Jersey border became part of I-95 while the eastern terminus of I-276 was cut back to the new interchange.[217][218]

With the creation of the Interstate Highway System, restaurants and gas stations were prohibited along Interstate Highways. When it joined the system the turnpike was grandfathered, allowing it to continue operating its service plazas.[219]

Speed limits

.jpg)

The turnpike had no enforced speed limit when it opened except for the tunnels, which had a 35-mile-per-hour (55 km/h) speed limit. Some drivers traveled as fast as 90 mph (145 km/h) on the road.[153] In 1941, speed limits of 70 mph (115 km/h) for cars and 50–65 mph (80–105 km/h) for trucks were enacted.[184] During World War II, the turnpike adopted the national speed limit of 35 mph (55 km/h);[2] after the war, the limit returned to 70 mph (115 km/h).[220]

In 1953, the speed limit on the portion of the highway between the Ohio border and Breezewood was lowered to 60 mph (95 km/h) to reduce the number of accidents, but returned to 70 mph (115 km/h) when the measure proved ineffective.[221][222] The limit on the turnpike was reduced to 65 mph (105 km/h) in 1956 for cars, buses and motorcycles, with other vehicles limited to 50 mph (80 km/h).[169] A minimum speed of 35 mph (55 km/h) was established in 1959;[223] it was raised to 40 mph (65 km/h) in 1965.[224]

With the passage of the 1974 National Maximum Speed Law, the speed limit on the turnpike was reduced to 55 mph (90 km/h).[225] It was again raised to 65 mph (105 km/h) in 1995, except for urban areas with a population greater than 50,000; the latter retained the 55 mph (90 km/h) speed limit.[226] In 2005, the turnpike commission approved raising the speed limit to 65 mph (105 km/h) for the entire length of the turnpike (except the tunnels, mainline toll plazas and the winding portion near the Allegheny Mountain Tunnel, which retained the 55 mph (90 km/h) limit).[227] On July 22, 2014, the speed limit increased to 70 mph (115 km/h) between the Blue Mountain and Morgantown interchanges.[228] On March 15, 2016, the Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission approved raising the speed limit on the remainder of the turnpike to 70 mph (115 km/h), excluding sections that are posted with a 55 mph (90 km/h) speed limit.[229][230] On May 3, 2016, the speed limit increased to 70 mph (115 km/h) on the 65 mph (105 km/h) sections of the toll road. The speed limit remains 55 mph (90 km/h) at construction zones, the tunnels, mainline toll plazas, the winding portion near the Allegheny Mountain Tunnel, and the section between Bensalem and the Delaware River Bridge.[231][232][233]

Tunnel modernization and realignment

As traffic levels increased, bottlenecks at the two-lane tunnels on the Pennsylvania Turnpike became a major problem. By the late 1950s, traffic jams formed at the tunnels, especially during the summer.[234] In 1959, four Senators urged state officials to work with the turnpike commission to study ways to reduce the traffic jams.[235] That year, the commission began studies aimed at resolving the traffic jams at the Laurel Hill and Allegheny Mountain tunnels; studies for the other tunnels followed.[236] At the conclusion of the studies, the turnpike commission planned to make the entire turnpike at least four lanes by either adding a second tube at the tunnels or bypassing them.[81] The new and upgraded tunnel tubes would feature white tiles, fluorescent lighting, and upgraded ventilation.[154]

The turnpike commission announced plans to build a second bore at the Allegheny Mountain Tunnel and a four-lane bypass of the Laurel Hill Tunnel in 1960. A bypass was planned for the Laurel Hill Tunnel because traffic would be more quickly and less expensively relieved than it would by boring another tunnel.[237] In 1962, the commission approved these two projects.[238] That August, $21 million in bonds were sold to finance the two projects.[239] The Laurel Hill Tunnel was bypassed using a deep cut to the north; it would feature a wide median, truck climbing lanes, and a 145-foot (44 m)-deep cut into the mountain.[154][240] Groundbreaking for the new alignment took place on September 6, 1962.[241] This bypass opened to traffic on October 30, 1964 at a cost of $7.5 million.[154][240] Work on boring the second tube at Allegheny Mountain Tunnel also began on September 6, 1962.[240] The former South Pennsylvania Railroad tunnel was considered, but was again rejected because of its poor condition.[242] On March 15, 1965, the new tube opened to traffic, after which the original tube was closed to allow updates to be made. It reopened on August 25, 1966.[240][243] The construction of the second tube at Allegheny Mountain cost $12 million.[154]

In 1965, the turnpike commission announced plans to build second tubes at the Tuscarora, Kittatinny, and Blue Mountain tunnels while a 13.5-mile (21.7 km) bypass of the Rays Hill and Sideling Hill tunnels would be built.[244] A bypass of these two tunnels was considered in the 1930s, but at the time was determined to be too expensive.[81] An early 1960s study concluded that a bypass would be the best option to handle traffic at Rays Hill and Sideling Hill.[81][245] This bypass of the two tunnels would have a 36-foot (11 m)-wide median with a steel barrier in the middle.[61] The commission sold $77.5 million in bonds in January 1966 to finance this project.[246] Construction of the bypass of the Rays Hill and Sideling Hill tunnels involved building a cut across both hills.[247][248] The new alignment began at the Breezewood interchange, where a portion of the original turnpike was used to access US 30.[249] In building the cut across Rays Hill, a portion of US 30 had to be realigned.[247] The cut over Sideling Hill passes over the Sideling Hill Tunnel.[248] The new alignment ends a short distance east of the Cove Valley service plaza on the original segment. The turnpike bypass of Rays Hill and Sideling Hill tunnels opened to traffic on November 26, 1968.[81] When the highway was realigned to bypass the Rays Hill and Sideling Hill tunnels, the Cove Valley service plaza on the original section was closed and replaced with the Sideling Hill service plaza (the only service plaza on the main turnpike serving travelers in both directions).[61] After traffic was diverted to the new alignment, the former stretch of roadway passing through the Rays Hill and Sideling Hill tunnels became known as the Abandoned Pennsylvania Turnpike. The turnpike commission continued to maintain the tunnels for a few years, but eventually abandoned them. The abandoned stretch deteriorated; signs and guardrails were removed, pavement started crumbling, trees grew in the median, and vandals and nature began taking over the tunnels. The turnpike commission still performed some maintenance on the abandoned stretch and used it for testing pavement marking equipment.[250] In 2001, the turnpike commission turned over a significant portion of the abandoned section to the Southern Alleghenies Conservancy; bicycles and hikers could use the former roadway.[251] The abandoned stretch of the turnpike is the longest stretch of abandoned freeway in the United States.[81]

Meanwhile, studies concluded that a parallel tunnel was the most economical option at the Tuscarora, Kittatinny, and Blue Mountain tunnels. Work on the new tube at the Tuscarora Mountain Tunnel began on April 11, 1966 while construction began at the Kittatinny and Blue Mountain tunnels a week later.[243] The parallel tubes at these three tunnels would open on November 26, 1968; the same day as the bypass of the Rays Hill and Sideling Hill tunnels. The original tubes were subsequently remodeled.[81] Both the new and remodeled tunnels would have fluorescent lighting, white tile walls, and 13 ft (4.0 m)-wide lanes.[252] The portals of the new tunnels were designed to resemble those of the original tunnels. Reconstruction of the original Tuscarora Mountain Tunnel was completed in October 1970, while work on refurbishing the original Kittatinny and Blue Mountain tunnels was finished on March 18, 1971.[253] With the completion of these projects, the entire length of the highway was at least four lanes wide.[254]

Late 20th century

The roadway's median, while initially thought to be wide enough, was considered too narrow by 1960. The turnpike commission installed median barriers at curves and high-accident areas starting in the 1950s.[255] In 1960, it began to install 100 miles (160 km) of median barrier along the turnpike.[256] Work was completed in December 1965 at a cost of $5 million.[6] In October 1963, work began on replacing the New Stanton interchange, which required left turns across traffic on the ramps and was frequently congested. The new, grade-separated interchange opened on November 12, 1964 and provided access to I-70 at the western end of the turnpike stretch of I-70/I-76.[257] A new interchange serving I-283 and PA 283 opened at Harrisburg East in 1969. Due to the realignment of US 222 to a four-lane freeway, a new Reading interchange was proposed.[258] This was opened on April 10, 1974.[259]

In 1968, the turnpike commission proposed converting the section of the road between Morgantown and the Delaware River Bridge from a ticket to a barrier system.[258] The project was canceled in 1971, due to a decline in revenue caused by the completion of I-80.[253] In 1969 the turnpike commission announced a 75-percent toll hike, the first such increase for cars.[260] This rise in tolls, which took place September 1 of that year, brought the toll rate to 2 cents per mile (1.2 ¢/km) or 14 ¢/mi (8.7 ¢/km) in 2018.[42][261]

In 1969, the turnpike commission said that because of increasing traffic, it was necessary to widen the turnpike. It proposed doubling the number of lanes from four to eight; the portion in the Philadelphia area was to be ten lanes wide. Cars and trucks would be carried on separate roadways under this plan.[262] The roadway would also have an 80 mph (130 km/h) speed limit and holographic road signs. This widening would have kept much of the routing intact, but significant realignments were proposed between the Allegheny Mountain and Blue Mountain tunnels.[263] Because of the $1.1 billion cost and the 1973 oil crisis that resulted in the imposition of a 55 miles per hour (89 km/h) speed limit, this plan was not implemented.[245] By the 1970s, the Pennsylvania Turnpike started to see a decline in the volume of traffic because of the opening of I-80—which provided a shorter route across the north of the state, and the 1973 oil crisis—which led to a decline in long-distance travel.[259][264] In the late 1970s, the turnpike commission proposed truck climbing lanes east of the Allegheny Mountain Tunnel near New Baltimore and near the Laurel Hill Bypass.[265] These were completed on December 2, 1981.[266]

In 1978, as the Howard Johnson's exclusive contract to provide food service was ending, the turnpike commission considered bids for competitors to provide food service.[267] That year ARA Services was awarded a contract for food service at two plazas, ending the Howard Johnson's monopoly.[268] The highway became the first toll road in the country to offer more than one fast-food chain at its service plazas.[269] At this time, gas stations along the turnpike were operated by Gulf Oil, Exxon, and ARCO.[268] Hardee's also opened restaurants at the service plazas in 1980 to compete with Howard Johnson's.[270] With this, the turnpike became the first road in the world to offer fast food at its service plazas.[271] Additionally, a toll increase of 22 percent was announced in 1978, effective August 1 of that year; this raised the rate to 2.2 cents per mile (1.4 ¢/km), or 8 ¢/mi (5.0 ¢/km) in 2018.[42][261][272]

The portion of the turnpike in the Philadelphia area had become a congested commuter road by the 1980s.[24] In 1983, funding was approved to widen the turnpike to six lanes between the Valley Forge and Philadelphia interchanges.[273] This planned project was put on hold because of disagreements between Governor Dick Thornburgh and the turnpike commission members, and differences between the commissioners.[274][275] The Pennsylvania Legislature approved the project in 1985; the road would be widened between the Norristown and Philadelphia interchanges.[276][277] Construction on the widening began on March 10, 1986,[278] and was completed on November 23, 1987 with a ribbon-cutting at the Philadelphia interchange. The widening project cost $120 million.[279] An interchange to serve the New Cumberland Defense Depot near Harrisburg was planned in the 1980s.[280] In 1992, the turnpike commission decided not to build it because it would instead build a connector road to the depot between PA 114 and Old York Road that would parallel the turnpike.[281]

Burger King and McDonald's opened on the Pennsylvania Turnpike in 1983.[269] This marked a transition from sit-down to fast-food dining on the turnpike by popular demand.[271] The Marriott Corporation purchased the remaining Howard Johnson's restaurants in 1987, incorporating it into its Host Marriott division and replacing them with restaurants such as Roy Rogers and Bob's Big Boy.[63]

In 1986, a toll hike of 30 percent was planned and the new rates went into effect on January 2, 1987.[261][282] With this increase, the toll rate was 3.1 cents per mile (1.9 ¢/km), or 7 ¢/mi (4.3 ¢/km) in 2018.[42][261] Motorists originally stopped at booths to receive toll tickets from turnpike staff, but in 1987 ticket machines replaced human workers.[283]

Plans to build an interchange connecting to the north end of I-476 (the Blue Route) were made; the turnpike commission approved a contract to build the interchange in March 1989.[284] That June, a losing bidder decided to challenge the turnpike commission, saying it violated female and minority contracting rules regarding the percentage of these employees that were used for the project. Under this rule, bidders were supposed to have at least 12 percent of contracts to minority-owned companies and at least 4 percent to female-owned companies. The losing bidder had 12.4 percent of the contracts to minority companies and 4.2 percent to female-owned companies while the winning bidder had 6.1 percent and 3.7 percent respectively. The turnpike commission decided to rebid the contract, but was sued by the original contractor. This dispute delayed the construction of the interchange.[285] The contract was rebid in November 1989 after the Pennsylvania Supreme Court permitted it.[286] The interchange between I-476 and the turnpike mainline was completed in November 1992; the ramps to the Northeast Extension opened a month later.[287][288] An official ribbon-cutting took place on December 15, 1992.[289]

In September 1990, the Morgantown interchange was relocated to provide a direct connection to I-176; the overhead interchange lights at the new exit were a nuisance to nearby residents.[290][291] An interchange was also proposed in 1990 with PA 743 between Elizabethtown and Hershey, but a study in 1993 determined that it would not improve traffic flow on area roads.[292][293] The turnpike commission celebrated the highway's 50th anniversary in 1990. $300,000 was spent to promote the turnpike through various means including a videotape, souvenirs, and a private party attended by politicians and companies that work with the turnpike.[294]

Gulf Oil LP (the modern-day successor to the original Gulf Oil after Standard Oil of California—now Chevron—bought Gulf in 1984) replaced the Exxon stations on the turnpike in 1990;[295] Sunoco took over operation of the gas stations from Gulf in 1993, outbidding Shell Oil.[296] In 1995, a farmers market was introduced to the Sideling Hill service plaza.[297]

An electronic toll collection system was proposed in 1990 where a motorist would create an account and use an electronic device which would be read from an electronic tollbooth; the motorist would be billed later.[298] The multi-state electronic tolling system E-ZPass was planned to go into effect by 1998;[299][300] however, implementation of the system was postponed until 2000.[301]

Another 30-percent toll increase went into effect on June 1, 1991 to fund expansion projects, bringing the rate to 4 cents per mile (2.5 ¢/km) or 7 ¢/mi (4.3 ¢/km) in 2018.[42][302][303]

Plans were made in 1993 to build a direct interchange between the turnpike and I-79 in Cranberry Township, Butler County.[304] A contract was awarded to build this interchange in November 1995.[305] In 1997, transportation officials agreed upon a design for the interchange.[306] The project also included moving the western end of the ticket system to a new toll plaza in Warrendale. The interchange project was delayed by a dispute with Marshall and Pine townships in Allegheny County, who wanted to prevent construction of the toll plaza as they thought it would cause noise, air and light pollution.[307] Marshall Township eventually agreed to allow the toll plaza be built.[308] Groundbreaking for the new interchange took place on February 22, 2002.[309] The westbound Butler service plaza was closed because the Warrendale toll plaza was to be located at its site.[310] On June 1, 2003, the plaza opened and the Gateway toll plaza became a flat-rate toll plaza, while all the exit toll plazas west of Warrendale closed.[311] The direct interchange between the turnpike and I-79, connecting to US 19, opened on November 12, 2003. The project cost $44 million.[312]

In 1996, plans were made to reconstruct the Irwin to Carlisle section of the turnpike along with the western part to the Ohio border.[313] A rebuilding project was proposed for the original section of the roadway in 1998. The first portion planned for construction was a 5-mile (8.0 km) stretch east of the Donegal interchange; a contract was awarded in June 1998.[314] This project involved the replacement of overpasses, widening of the median, and the complete repaving of the road.[314][315] The rebuilding was due for completion in 2014, with a projected cost of $5 million per mile ($3,100,000/km).[316] During the reconstruction, the turnpike commission used a humorous advertising campaign called "Peace, Love and the Pennsylvania Turnpike". It ran for 90 days in 2001, and used tie-dyed billboards that resembled those from the 1970s and carried phrases such as "Rome wasn't built in a day" and "Spread the love. Let someone merge."[317]

In 1996, a study on improving the Allegheny Mountain Tunnel by either building another tube or by constructing a bypass was carried out.[318][319] Based on the study, the turnpike commission planned to replace the deteriorating tunnel with a cut through the mountain.[319] The plans were put on hold in 2001 because it would cost $93.7 million. It resurrected the project in 2009.[320] The nearby Mountain Field and Stream Club prefers that the tunnels be improved or a new tube built rather than building the bypass. These improvements are needed because the Allegheny Mountain Tunnel is narrow and deteriorating, with disintegrating ceiling slabs and outdated lighting and ventilation.[321]

Construction began in 1998 to improve the bridge over the Schuylkill River in Montgomery County. The work involved building a new bridge adjacent to the existing bridge; the new bridge was wide enough to accommodate a future widening to six lanes. This project was completed in 2000.[322]

A study began in 1999 to widen the road to six lanes between Valley Forge and Norristown.[323] In October 2004, work began on widening this stretch of road,[324] which was completed in November 2008 at a cost of $330 million.[325]

21st century

In 2000, the turnpike commission announced plans to build a new bridge, a segmental concrete bridge wider than the original, over the Susquehanna River.[326] In 2004, work began on building the new, six-lane bridge which cost $150 million. On May 16, 2007, a ribbon-cutting took place to mark the completion of the westbound direction of the bridge, which opened to traffic the following day.[21][327] The eastbound direction of the bridge opened a month later.[328]

In October 2000, the turnpike commission announced the road would be switching from sequential exit numbering to distance-based exit numbering. At first, both exit numbers would exist, but the old numbers would be phased out.[329][330] Work began on posting the new exit numbers in 2001.[331]

On December 2, 2000, E-ZPass debuted on the turnpike between Harrisburg West and the Delaware River Bridge.[332][333][334] By December 15, 2001, E-ZPass could be used on the entire length of the Pennsylvania Turnpike.[335][336] Commercial vehicles were allowed to use the system beginning on December 14, 2002.[337]

On June 1, 2003, the Warrendale toll plaza became the west end of the ticket system; the Gateway toll plaza became a flat-rate plaza and toll booths at the New Castle, Beaver Valley, and Cranberry interchanges were closed.[311] Express E-ZPass lanes opened at the Warrendale toll plaza in June 2004, which allowed motorists to travel through the toll plaza at highway speeds.[338]

On August 1, 2004, tolls increased by 42 percent to a rate of 5.9 cents per mile (3.7 ¢/km), or 8 ¢/mi (5.0 ¢/km) in 2018,[42] to provide money for road construction.[339] On November 24, 2004 (the day before Thanksgiving), 2,000 Teamsters Union employees went on the first strike in the turnpike's history after contract negotiations failed. Since this is usually one of the busiest travel days in the United States, to avoid traffic jams tolls were waived for the rest of the day.[340] Beginning on November 25, 2004, turnpike management personnel collected flat-rate cash passenger tolls of $2 and commercial tolls of $15 on the ticketed system, while E-ZPass customers were charged the lesser amount of the toll or the flat rate.[341] The strike ended after seven days, when both sides reached an agreement on November 30, 2004, normal toll collection resumed December 1, 2004.[342]

In 2004, proposals to widen the highway to six lanes between Downingtown and Valley Forge were made.[343] In 2007, the western terminus of the widening project was scaled back from Downingtown to the proposed PA 29 slip ramp.[344] Plans for the widening were presented to the public in 2009.[345] Later that year, the widening was put on hold because of engineering problems.[346] The widening plans resumed in 2010.[347] Work was due to begin in 2013, with completion in 2015.[348] In October 2012, the project was postponed a year because of delays in the approval of permits.[349]