Emilie Schenkl

Emilie Schenkl (26 December 1910 – 13 March 1996) was the wife[1] (or companion)[2][lower-alpha 1] of Subhas Chandra Bose—a major leader of Indian nationalism—and the mother of their daughter, Anita Bose Pfaff (born 29 November 1942).[1][3] Schenkl, an Austrian, and her baby daughter were left without support in wartime Europe by Bose, following his departure for Southeast Asia in February 1943 and death in 1945.[4] In 1948, both were met by Bose's brother Sarat Chandra Bose and his family in Vienna in an emotional meeting.[5] In the post-war years, Schenkl worked shifts in the trunk exchange and was the main breadwinner of her family, which included her daughter and her mother. [6]

Emilie Schenkl | |

|---|---|

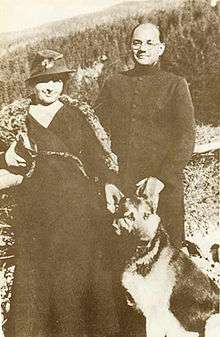

Emilie Schenkl with Subhas Chandra Bose | |

| Born | Emilie Schenkl 26 December 1910 |

| Died | 13 March 1996 (aged 85) Vienna, Austria |

| Nationality | Austro-Hungarian (1910–18) Austro-German (1918–19) Austrian (1919–96) |

| Occupation | Stenographer |

| Spouse(s) | Subhas Chandra Bose (1937–1945; his death) |

| Children | Anita Bose Pfaff (b. 1942) |

Early life

Emilie Schenkl was born in Vienna on 26 December 1910 in an Austrian Catholic family.[7] Paternal granddaughter of a shoemaker and the daughter of a veterinarian, she started primary school late—towards the end of the Great war—on account of her father's reluctance for her to have formal schooling.[7] Her father, moreover, became unhappy with her progress in secondary school and enrolled her in a nunnery for four years.[7] Schenkl decided against becoming a nun and went back to school, finishing when she was 20.[7] The Great Depression had begun in Europe; consequently, for a few years she was unemployed.[7]

She was introduced to Bose through a mutual friend, Dr. Mathur, an Indian physician living in Vienna.[7] Since Schenkl could take shorthand and her English and typing skills were good, she was hired by Bose, who was writing his book, The Indian Struggle.[7] They soon fell in love and were married in a secret Hindu ceremony in 1937,[1][2] but without a Hindu priest, witnesses, or civil record. Bose went back to India and reappeared in Nazi Germany during April 1941–February 1943.

Berlin during the war

Soon, according to historian Romain Hayes, "the (German) Foreign Office procured a luxurious residence for (Bose) along with a butler, cook, gardener, and an SS-chauffeured car. Emilie Schenkl moved in openly with him. The Germans, aware of the nature of the relationship, refrained from any involvement."[3] However, most of the staff in the Special Bureau for India, which had been set up to aid Bose, did not get along with Emilie.[8] In particular Adam von Trott, Alexander Werth and Freda Kretschemer, according to historian Leonard A. Gordon, "appear to have disliked her intensely. They believed that she and Bose were not married and that she was using her liaison with Bose to live an especially comfortable life during the hard times of war" and that differences were compounded by issues of class.[8] In November 1942, Schenkl gave birth to their daughter. In February 1943, Bose left Schenkl and their baby daughter and boarded a German submarine to travel, via transfer to a Japanese submarine, to Japanese-occupied southeast Asia, where with Japanese support he formed a Provisional Government of Free India and revamped an army, the Indian National Army, whose goal was to gain India's independence militarily with Japanese help. Bose's military effort, however, was unsuccessful.[9]

Later life

Schenkl and her daughter survived the war.[4][10] During their nine years of marriage, Schenkl and Bose spent less than three years together, putting strains on Schenkl.[6] In the post-war years, Schenkl worked shifts in the trunk exchange and was the main breadwinner of her family, which included her daughter and her mother.[6] Although some family members from Bose's extended family, including his brother Sarat Chandra Bose, welcomed Schenkl and her daughter and met with her in Austria, Schenkl never visited India. According to her daughter, Schenkl was a very private woman and tight-lipped about her relationship with Bose.[6] Schenkl died in 1996.

Notes

- Gordon comments: "Although we must take Emilie Schenkl at her word (about her secret marriage to Bose in 1937), there are a few nagging doubts about an actual marriage ceremony because there is no document that I have seen and no testimony by any other person. ... Other biographers have written that Bose and Miss Schenkl were married in 1942, while Krishna Bose, implying 1941, leaves the date ambiguous. The strangest and most confusing testimony comes from A. C. N. Nambiar, who was with the couple in Badgastein briefly in 1937, and was with them in Berlin during the war as second-in-command to Bose. In an answer to my question about the marriage, he wrote to me in 1978: 'I cannot state anything definite about the marriage of Bose referred to by you, since I came to know of it only a good while after the end of the last world war ... I can imagine the marriage having been a very informal one ...' ... So what are we left with? ... We know they had a close passionate relationship and that they had a child, Anita, born 29 November 1942, in Vienna. ... And we have Emilie Schenkl's testimony that they were married secretly in 1937. Whatever the precise dates, the most important thing is the relationship."[2]

Citations

- Hayes 2011, p. 15.

- Gordon 1990, pp. 344–345.

- Hayes 2011, p. 67.

- Bose 2005, p. 255.

- Gordon 1990, p. 595–596.

- Santhanam 2001.

- Gordon 1990, p. 285.

- Gordon 1990, p. 446.

- Gordon 1990, p. 543.

- Hayes 2011, p. 144.

References

- Bose, Sarmila (2005), "Love in the Time of War: Subhas Chandra Bose's Journeys to Nazi Germany (1941) and towards the Soviet Union (1945)", Economic and Political Weekly, 40 (3): 249–256, JSTOR 4416082

- Bose, Sugata (2011), His Majesty's Opponent: Subhas Chandra Bose and India's Struggle against Empire, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-04754-9, retrieved 22 September 2013

- Gordon, Leonard A. (1990), Brothers against the Raj: a biography of Indian nationalists Sarat and Subhas Chandra Bose, Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0-231-07442-1, retrieved 17 November 2013

- Hayes, Romain (2011), Subhas Chandra Bose in Nazi Germany: Politics, Intelligence and Propaganda 1941-1943, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-932739-3, retrieved 22 September 2013

- Pelinka, Anton (2003), Democracy Indian Style: Subhas Chandra Bose and the Creation of India's Political Culture, Transaction Publishers, ISBN 978-1-4128-2154-4, retrieved 17 November 2013

- Santhanam, Kausalya (1 March 2001), "Wearing the mantle with grace", The Hindu, retrieved 31 December 2013