River Derwent (Tasmania)

The River Derwent is a river located in Tasmania, Australia. It is also known by the palawa kani name timtumili minanya.[3] The river rises in the state's Central Highlands at Lake St Clair, and descends more than 700 metres (2,300 ft) over a distance of more than 200 kilometres (120 mi), flowing through Hobart, the state's capital city, before emptying into Storm Bay and flowing into the Tasman Sea. The banks of the Derwent were once covered by forests and occupied by Tasmanian Aborigines. European settlers farmed the area and during the 20th century many dams were built on its tributaries for the generation of hydro-electricity.

| River Derwent timtumili minanya | |

|---|---|

Sunrise over the River Derwent | |

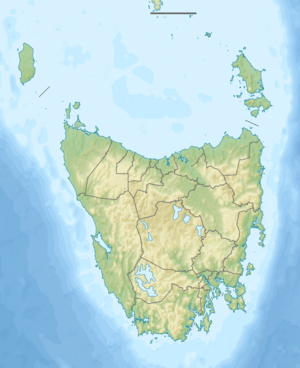

Location of the river mouth in Tasmania | |

| Native name | timtumili minanya |

| Location | |

| Country | Australia |

| State | Tasmania |

| Cities | Derwent Bridge, New Norfolk, Hobart |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Lake St Clair |

| • location | Central Highlands |

| Source confluence |

|

| • location | Cradle Mountain-Lake St Clair National Park |

| • coordinates | 42°7′12″S 146°12′37″E |

| • elevation | 738 m (2,421 ft) |

| Mouth | Storm Bay |

• location | Hobart |

• coordinates | 43°3′3″S 147°22′38″E |

• elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Length | 239 km (149 mi) |

| Basin size | 9,832 km2 (3,796 sq mi) |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Storm Bay |

| • average | 90 m3/s (3,200 cu ft/s) |

| • minimum | 50 m3/s (1,800 cu ft/s) |

| • maximum | 140 m3/s (4,900 cu ft/s) |

| Basin features | |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | Nive River, Dee River, River Ouse, Clyde River, Jordan River |

| • right | Repulse River, Tyenna River, Styx River, Plenty River, Lachlan River |

| Natural lakes | Saint Clair Lagoon; Lake Saint Clair |

| [1][2] | |

Agriculture, forestry, hydropower generation and fish hatcheries dominate catchment land use. The Derwent is also an important source of water for irrigation and water supply. Most of Hobart's water supply is taken from the lower River Derwent.[4] Nearly 40% of Tasmania's population lives around the estuary's margins and the Derwent is widely used for recreation, boating, recreational fishing, marine transportation and industry.[2]

Etymology

It was named after the River Derwent, Cumbria, by British Commodore John Hayes who explored it in 1793. The name is Brythonic Celtic for "valley thick with oaks".[5][6] John Hayes placed the name "River Derwent" only in the upper part of the river. Matthew Flinders placed the name "Derwent River" on all of the river.[7]

History

The River Derwent valley was inhabited by the Mouheneener people for at least 8,000 years before British settlement.[8] Evidence of their occupation is found in many middens along the banks of the river. In 1793, John Hayes named it after the River Derwent, which runs past his birthplace of Bridekirk, Cumberland.[9]

When first explored by Europeans, the lower parts of the valley were clad in thick she-oak forests, remnants of which remain in various parts of the lower foreshore.[10]

There was a thriving whaling industry until the 1840s when the industry rapidly declined due to over-exploitation.[11]

Geography

Formed by the confluence of the Narcissus and Cuvier rivers within Lake St Clair, the Derwent flows generally southeast over a distance of 187 kilometres (116 mi) to New Norfolk and the estuary portion extends a further 52 kilometres (32 mi) out to the Tasman Sea. Flows average in range from 50 to 140 cubic metres per second (1,800 to 4,900 cu ft/s) and the mean annual flow is 90 cubic metres per second (3,200 cu ft/s).[10]

The large estuary forms the Port of the City of Hobart – often claimed to be the deepest sheltered harbour in the Southern Hemisphere; some past guests of the port include HMS Beagle in February 1836, carrying Charles Darwin; the USS Enterprise; and USS Missouri. The largest vessel to ever travel the Derwent is the 113,000-tonne (111,000-long-ton), 61-metre (200 ft) high, ocean liner Diamond Princess, which made her first visit in January 2006.[12]

At points in its lower reaches the river is nearly 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) wide, and as such is the widest river in Tasmania.

Hydro schemes

Until the construction of several hydro-electric dams between 1934 and 1968, the river was prone to flooding. Now there are more than twenty dams and reservoirs used for the generation of hydro-electricity on the Derwent and its tributaries, including the Clyde, Dee, Jordan, Nive, Ouse, Plenty and Styx rivers. Seven lakes have been formed by damming the Derwent and the Nive rivers for hydroelectric purposes and include the Meadowbank, Cluny, Repulse, Catagunya, Wayatinah, Liapootah and King William lakes or lagoons.

River health

The Upper Derwent is affected by agricultural run-off, particularly from land clearing and forestry. The Lower Derwent suffers from high levels of heavy metal contamination in sediments. The Tasmanian Government-backed Derwent Estuary Program has commented that the levels of mercury, lead, zinc and cadmium in the river exceed national guidelines. In 2015 the program recommended against consuming shellfish and cautioned against consuming fish in general. Nutrient levels in the Derwent between 2010 and 2015 increased in the upper estuary (between Bridgewater and New Norfolk) where there had been algal blooms.[10]

A large proportion of the heavy metal contamination has come from major industries that discharge into the river including the former Electrolytic Zinc[13][14][15][16] and now Nyrstar smelter at Lutana established in 1916,[17] and a paper mill at Boyer which opened in 1941.

The Derwent adjoins or flows through the Pittwater–Orielton Lagoon, Interlaken Lakeside Reserve and Goulds Lagoon, all wetlands of significance protected under the Ramsar Convention.[2]

Flora and fauna

In recent years, southern right whales finally started making appearance in the river during months in winter and spring when their migration takes place. Some females even started using calm waters of the river as a safe ground for giving birth to their calves and would stay over following weeks after disappearance of almost 200 years due to being wiped out by intense whaling activities. In the winter months of 2014, humpback whales and a minke whale (being the first confirmed record of this species in the river) have been recorded feeding in the River Derwent for the first time since the whaling days of the 1800s.[18]

Bridges

Several bridges connect the western shore (the more heavily populated side of the river) to the eastern shore of Hobart – in the greater Hobart area, these include the five lane Tasman Bridge, near the CBD, just north of the port; the four lane Bowen Bridge; and the two lane Bridgewater Bridge and Causeway. Until 1964 the Derwent was crossed by the unique Hobart Bridge, a floating concrete structure just upstream from where the Tasman Bridge now stands.[19]

Travelling further north from the Bridgewater crossing, the next crossing point is New Norfolk Bridge, slightly north of the point where the Derwent reverts from seawater to fresh water, Bushy Park, Upper Meadowbank Lake, Lake Repulse Road, Wayatinah, and the most northerly crossing is at Derwent Bridge, before the river reaches its source of Lake St Clair. At the Derwent Bridge crossing, the flow of the river is generally narrow enough to be stepped across.

Cultural references

The river is the subject of the multimedia performance "Falling Mountain" (2005 Mountain Festival), a reference to the mountain in the Cradle Mountain-Lake St Clair National Park from which the river rises.

The Derwent is mentioned in the song, Mt Wellington Reverie by Australian band, Augie March.[20] Hobart is located in the foothills of Mount Wellington.

Panoramas

See also

References

- "Map of River Derwent, TAS". Bonzle Digital Atlas of Australia. 2015. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- "Derwent Estuary and its catchment". Department of the Environment. Australian Government. Archived from the original on 3 July 2015. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- "Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre – nipaluna". tacinc.com.au. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

- "Catchment and flow". Derwent Estuary Program. 16 October 2014. Archived from the original on 3 July 2015. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- Names of Rivers Archived 18 July 2006 at the Wayback Machine web.ukonline.co.uk

- Celtic Place Names Archived 6 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine www.yorksj.ac.uk

- Observations on the coasts of Van Diemen's Land, on Bass's Strait and its islands, and on parts of the coasts of New South Wales; intended to accompany the charts of the late discoveries in those countries. By Matthew Flinders, second lieutenant of His Majesty's Ship Reliance.published by John Nichols 1801* page 5

- Parliament of Tasmania – House of Assembly Standing Orders Archived 4 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine "We acknowledge the traditional people of the land upon which we meet today, the Mouheneener people."

- Roe, Margriet (1966). "Hayes, Sir John (1768–1831)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Melbourne University Press. ISSN 1833-7538. Retrieved 20 August 2009 – via National Centre of Biography, Australian National University.

- Shannon, Lucy (23 April 2015). "River Derwent: Heavy metal contamination decreases, effluent increases, report finds". ABC News. Australia. Archived from the original on 4 July 2015. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- "A History of Shore-Based Whaling". Parks.tas.gov.au. 25 July 2008. Archived from the original on 12 June 2008. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- "Shipping Movements List for Hobart". TasPorts. Australia. Archived from the original on 27 March 2016. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- Environmental Geochemistry Services; Tasmania. Dept. of Environment and Planning; Menzies Centre for Population Health Research; John Miedecke and Partners (1991), Investigation of heavy metals in soil and vegetation around the Pasminco Metals-EZ refinery, Hobart : stage 1, Dept. of Environment and Planning, retrieved 12 June 2015

- Environmental Geochemistry International; Tasmania. Dept. of Environment and Planning; John Miedecke and Partners (1992), Heavy metals in soil and vegetation in the vicinity of the Pasminco Metals-EZ refinery, Hobart, Dept. of Environment and Planning, retrieved 12 June 2015

- TASUNI Research. Aquahealth Division; Jeffries, Maria; Tasmania. Department of Primary Industry and Fisheries; Australian Government Analytical Laboratories; Tasmania. Department of Environment and Land Management; Lutana Soil Contamination Working Group (Tas.) (1995), Investigation of heavy metals in indoor dust, soils and home-grown vegetables : investigations in the vicinity of the Pasminco Metals-EZ refinery, Hobart, Dept. of Environment and Land Management, retrieved 12 June 2015

- Dames & Moore; Pasminco Metals – EZ; Pasminco Australia Limited (1995), Development proposal & environmental management plan : a proposal to implement the paragoethite co-treatment process at Pasminco Metals-EZ, Pasminco Ltd, retrieved 12 June 2015

- Ruth Barton. "Communal life, common interests and healthy conditions". Archived from the original on 14 February 2012.

- "It's mighty mouth: Whales feeding in River Derwent". Archived from the original on 26 August 2014. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- "Parliament of Tasmania History site – Hobart to Tasman Bridge". Parliament.tas.gov.au. 5 January 1975. Archived from the original on 21 April 2013. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 14 September 2009. Retrieved 18 April 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) augie-march.com Retrieved 6 January 2013

External links

- Derwent Estuary Program

- Upper Derwent Issues

- "Upper Derwent Catchment: Land Tenure and Water Uses" (PDF) (Map). Environment Protection Agency. Tasmanian Government. December 2000.

- "Derwent River (sic) Catchment: Environmental Management Goals" (PDF). Environment Protection Agency. Tasmanian Government. April 2003.