Tasman Bridge

The Tasman Bridge is a five-lane road bridge that carries the Tasman Highway (A3) across the Derwent River and the Southern rail line, located near the central business district of Hobart, Tasmania, Australia. Including approaches, the bridge has a total length of 1,396 metres (4,580 ft) and it provides the main traffic route from the CBD (on the western shore) to the eastern shore. The bridge has a separated pedestrian footway on each side. There is no dedicated lane for bicycles; however, steps to the pedestrian footway were replaced with ramps in 2010.[4]

Tasman Bridge | |

|---|---|

| |

| Coordinates | 42°51′54″S 147°20′33″E |

| Carries | Tasman Highway |

| Crosses |

|

| Locale | Hobart, Tasmania, Australia |

| Maintained by | Department of State Growth |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Prestressed concrete Girder |

| Total length | 1,395 metres (4,577 ft) |

| Width | 17.5 metres (57 ft) |

| Height | 60.5 metres (198 ft) |

| Longest span | 95 metres (312 ft) |

| Clearance below | 46 metres (151 ft) |

| History | |

| Construction start | May 1960[1] |

| Construction end | 23 December 1964 |

| Statistics | |

| Daily traffic | 67,000[2][3] |

| |

History

In the 1950s with the development of the Eastern shore, it was decided to build a larger bridge; the old Hobart Bridge faced increasing difficulty in managing the larger volumes of traffic that came with development, and constantly raising the lift span for shipping was disruptive. The total cost of the new bridge in conjunction with approach ramps and Lindisfarne Interchange was in the area of A£7 million.[5] Construction commenced in May 1960 and the bridge was first opened to traffic (2 lanes only) on 18 August 1964. The bridge was completed with all four lanes operational on 23 December 1964. It was officially opened on 18 March 1965 by Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester. During peak construction a labour force of over 400 men was employed on site.[5]

Disaster

On Sunday 5 January 1975, at 9:27 p.m. Australian Eastern Summer Time, the Tasman Bridge was struck by the bulk ore carrier Lake Illawarra,[1] bound for the Electrolytic Zinc Company with a cargo of 9,072 tonnes (10,000 short tons) of zinc concentrate.[1] It caused two pylons and three sections of concrete decking, totalling 127 metres (417 ft), to fall from the bridge and sink the ship. Seven of the ship's crewmen were killed, and five motorists died when four cars drove over the collapsed sections before the traffic was stopped. A major press shot showed a Holden Monaro HQ GTS, which was owned by Frank and Sylvia Manley, along with an older EK Holden station wagon, driven by a local man, Murray Ling, perched balancing on the ledge.[6]

The depth of the river at this point (35 metres (115 ft)) is such that the wreck of Lake Illawarra still lies on the bottom, with concrete slab on top of it, without presenting a navigation hazard to smaller vessels.

The breakage of an important arterial link isolated the residents in Hobart's eastern suburbs – the relatively short drive across the Tasman Bridge to the city suddenly became a 50-kilometre (31 mi) journey via the estuary's next bridge at Bridgewater. The only other vehicular crossing within Hobart after the bridge collapsed was the Risdon Punt, a cable ferry which crossed the river from East Risdon and Risdon, some five kilometres upstream from the bridge. However, it was totally inadequate, carrying only eight cars on each crossing, and although ferries provided a service across the Derwent River, it was not until December 1975 that a two lane, 788-metre-long (2,585 ft) Bailey bridge was opened to traffic, thereby restoring some connectivity.

The separation of Hobart saw an immediate surge in the small and limited ferry service then operating across the river.[1] In a primary position to provide a service were the two ships of Robert Clifford, a Tasmanian mariner. He had introduced the locally-built ferries Matthew Brady and James McCabe to the river crossing, from the Central Business District of Hobart to the eastern shore, shortly before the collision. These two ships were soon joined by the Cartela, a wooden vessel of 1912 vintage, and other ships, including Sydney Harbour ferries, pressed into service by the Tasmanian Government, to ferry thousands of commuters across the river.

Following successful rebuilding of the Bridge, Clifford's organisation saw the ferry traffic fade quickly, but by then he had diversified into further building of ships.

On 20 June 2007, a crane toppled whilst carrying out works on the bridge, and precariously hung for a number of hours off the side of the barriers.[7]

Reconstruction

Reconstruction of the Tasman Bridge commenced in October 1975. An important factor of the reconstruction is the improved safety measures. Some examples:

- Large vessels passing beneath the bridge must now do so slightly to the west of the original main navigation span.

- Personnel controlling ships (or harbor pilots) must be trained and then cleared for using the special laser lighthouse that indicates by colours whether the ship must be steered left or right to regain the centre line.

- All road traffic is now halted whilst large vessels transit beneath the bridge.

On top of the new safety measures implemented, the bridge was further upgraded to hold a fifth lane.[1][8] This upgrade included the construction of a lane management system which would enable the new middle lane to function as a reversible lane. The system consists of a traffic light system and a sign above each lane, pictured right. The signs, in conjunction with the traffic light system, employ a pulley system to periodically pull the signs over their appropriate lanes.

The middle lane points towards the city side (or western shore) during a.m. peak hours and points back towards the eastern shore during p.m. peak hours. The lane generally points towards the eastern shore during non-peak hours.

The Tasman Bridge repair took two years and cost approximately $44 million.[8] The bridge officially reopened on 8 October 1977.[1][8]

Replacement

In 2010, Clarence Alderman Richard James stated that it was time to consider the replacement of the Tasman Bridge with a new bridge of suspension or cable stay design, citing that the current bridge was facing a greatly reduced lifespan due to damage to the internal steel structure caused by the Tasman Bridge disaster. Richard James has suggested a timeframe of no more than 20 years, however Alderman James is not a qualified engineer.[9]

Gallery

View of the bridge from the eastern shore

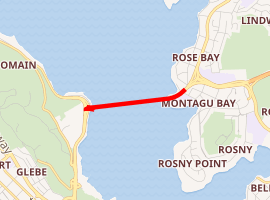

View of the bridge from the eastern shore Looking towards the Tasman Bridge from Montagu Bay

Looking towards the Tasman Bridge from Montagu Bay- Dinghy and the bridge.

The repaired bridge span

The repaired bridge span The view of the Bridge from Mount Wellington

The view of the Bridge from Mount Wellington A view of the bridge from the river

A view of the bridge from the river- Tasman Bridge from the Western shore

Entering the bridge from the eastern shore

Entering the bridge from the eastern shore.jpg) Entering the bridge from the west side

Entering the bridge from the west side

References

- "Tasmanian Year Book, 2000". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2002. Retrieved 22 February 2008.

- "Linear Infrastructure" (PDF). Department of Infrastructure, Energy and Resources. 2007. Retrieved 5 May 2007.

- "Traffic Jams". Stateline Tasmania. 2007. Retrieved 22 February 2008.

- "Cycling South Tasmania - Tasman Hwy and Bridge". 2010. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

- "Tasman Bridge Statistics". Tasmanian Government. 2004. Retrieved 4 March 2007.

- "Bridge gone". Tasmanian Government. 2000. Retrieved 22 February 2008.

- "Crane drama on Tasman Bridge". The Mercury. 21 June 2007. Archived from the original on 26 June 2007. Retrieved 22 February 2008.

- "Tasman Bridge disaster". Clarence City Council. 2004. Retrieved 22 February 2008.

- http://www.themercury.com.au/article/2010/12/17/193921_tasmania-news.html

- Reference: Lewis, Tom. By Derwent Divided. Darwin: Tall Stories, 1999.

- Ludeke, M. (2006) Ten Events Shaping Tasmania's History. Hobart: Ludeke Publishing.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tasman Bridge. |

- Live webcam view of Hobart including the Tasman Bridge

- Traffic camera view of the Tasman Bridge

- Archival photographs of construction of the Tasman Bridge: page 1, page 2.

- 1995 article about Tasman Bridge safety

- Hobart To Tasman Bridge 1938-2000

- Tasman Bridge at Structurae