Religion in Serbia

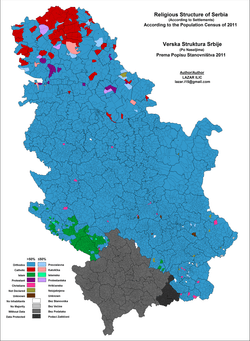

Serbia has been traditionally a Christian country since the Christianization of Serbs by Clement of Ohrid and Saint Naum in the 9th century. The dominant confession is Eastern Orthodoxy of the Serbian Orthodox Church. During the Ottoman rule of the Balkans, Sunni Islam established itself in the territories of Serbia, mainly in southern regions of Raška (or Sandžak) and Preševo Valley, as well as in the disputed territory of Kosovo and Metohija. The Catholic Church has roots in the country since the presence of Hungarians in Vojvodina (mainly in the northern part of the province), while Protestantism arrived in the 18th and 19th century with the settlement of Slovaks in Vojvodina.

Demographics

| 1921[2] | 1953[3] | 1991[3] | 2002[4][3] | 2011[3] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| Eastern Orthodox | 3,321,090 | 75.85 | 4,422,330 | 71.66 | 6,347,026 | 81.8 | 6,371,584 | 84.98 | 6,079,395 | 84.59 |

| Catholic | 751,429 | 17.16 | 607,612 | 9.85 | 496,226 | 6.4 | 410,976 | 5.48 | 356,957 | 4.97 |

| Protestant | no data | no data | 111,556 | 1.81 | 86,894 | 1.12 | 78,646 | 1.05 | 71,284 | 0.99 |

| Other Christian | 33,257 | 0.54 | 1,381 | 0.02 | 2,191 | 0.03 | 3,211 | 0.04 | ||

| "Christian" | 12,882 | 0.17 | 45,083 | 0.63 | ||||||

| Muslim | 97,672 | 2.23 | 155,657 | 2.52 | 224,120 | 2.89 | 239,658 | 3.2 | 222,829 | 3.1 |

| Jewish | 26,464 | 0.6 | 1,083 | 0.02 | 740 | 0.01 | 785 | 0.01 | 578 | 0.01 |

| Eastern religions | no data | no data | no data | no data | no data | no data | 240 | 0.00 | 1,237 | 0.02 |

| Irreligious / Atheist | no data | no data | 826,954 | 13.4 | 159,642 | 2.06 | 40,068 | 0.53 | 80,053 | 1.11 |

| Agnostic | 4,010 | 0.06 | ||||||||

| Declined to answer | 197,031 | 2.63 | 220,735 | 3.07 | ||||||

| Other | 181,940 | 4.16 | 1,796 | 0.03 | 13,982 | 0.18 | 6,649 | 0.09 | 1,776 | 0.02 |

| Unknown | 10,768 | 0.17 | 429,560 | 5.54 | 137,291 | 1.83 | 99,714 | 1.39 | ||

| Total | 4,378,595 | 100 | 6,171,013 | 100 | 7,759,571 | 100 | 7,498,001 | 100 | 7,186,862 | 100 |

Christianity

Eastern Orthodoxy

Most of the citizens of Serbia are adherents of the Serbian Orthodox Church, while the Romanian Orthodox Church is also present in parts of Vojvodina inhabited by ethnic Romanian minority. Besides Serbs, other Eastern Orthodox Christians include Montenegrins, Romanians, Macedonians, Bulgarians, Vlachs and majority of Roma people.

Eastern Orthodox Christianity predominates throughout most of Serbia, excluding several municipalities and cities near border with neighboring countries where adherents of Islam or Catholicism are more numerous as well as excluding two predominantly Protestant municipalities in Vojvodina. Eastern Orthodoxy also predominates in most of the large cities of Serbia, excluding the cities of Subotica (which is mostly Catholic) and Novi Pazar (which is mostly Muslim).

The identity of ethnic Serbs was historically largely based on Eastern Orthodox Christianity and on the Serbian Orthodox Church, to the extent that there are claims that those who are not its faithful are not Serbs. However, the conversion of the south Slavs from paganism to Christianity took place before the Great Schism, the split between the Greek East and the Latin West. After the Schism, generally speaking, those Christians who lived within the Eastern Orthodox sphere of influence became "Eastern Orthodox" and those who lived within the Catholic sphere of influence, under Rome as the patriarchal see of the West, became "Catholic." Some ethnologists consider that the distinct Serb and Croat identities relate to religion rather than ethnicity. With the arrival of the Ottoman Empire, some Serbs converted to Islam. This was particularly, but not wholly, so in Bosnia. The best known Muslim Serb is probably either Mehmed Paša Sokolović or Meša Selimović. Since the second half of the 19th century, some Serbs converted to Protestantism, while historically some Serbs also were Latin Rite Catholic (especially in Dalmatia) or Eastern Catholic.

Catholic Church

Catholic Church is present mostly in the northern part of Vojvodina, notably in the municipalities with Hungarian ethnic majority (Bačka Topola, Mali Iđoš, Kanjiža, Senta, Ada, Čoka) and in the multi-ethnic city of Subotica and multi-ethnic municipality of Bečej. It is represented mainly by the following ethnic groups: Hungarians, Croats, Bunjevci, Germans, Slovenes, Czechs, etc. A smaller number of Roma people, Slovaks and Serbs are also Catholic. The ethnic Rusyns and a smaller part of the ethnic Ukrainians are primarily Eastern Rite Catholics.

Protestantism

The largest percentage of the Protestant Christians in Serbia on municipal level is in the municipalities of Bački Petrovac and Kovačica, where the absolute or relative majority of the population are ethnic Slovaks (most of whom are adherents of Protestant Christianity). Some members of other ethnic groups (especially Serbs in absolute terms and Hungarians and Germans in proportional terms) are also adherents of various forms of Protestant Christianity.

There are various neo-Protestant groups in the country, including Methodists, Seventh-day Adventists, Evangelical Baptists (Nazarene), and others. Many of these groups are situated in the culturally diverse province of Vojvodina. Prior to end of World War II number of Protestants in the region was larger.

According to the 2011 census, the largest Protestant communities were recorded in the municipalities of Kovačica (11,349) and Bački Petrovac (8,516), as well as in Stara Pazova (4,940) and the second largest Serbian city Novi Sad (8,499), which are predominately Eastern Orthodox.[5] While Protestants from Kovačica, Bački Petrovac and Stara Pazova are mostly Slovaks, members of Slovak Evangelical Church of the Augsburg Confession in Serbia, services in most of the Protestant churches in Novi Sad are performed in the Serbian language.[6]

Protestantism (mostly in its Nazarene form) started to spread among Serbs in Vojvodina in the last decades of the 19th century. Although the percentage of Protestants among Serbs is not large, it is the only religious form besides Eastern Orthodoxy, which is today widespread among Serbs.

Islam

Islam is mostly present in the southwest of Serbia in the region of Sandžak or Raška (notably in the city of Novi Pazar and municipalities of Tutin and Sjenica), as well as in parts of southern Serbia (municipalities of Preševo and Bujanovac). Ethnic groups whose members are mostly adherents of Islam are: Bosniaks, Muslims by nationality, Albanians, and Gorani. A significant number of Roma people are also adherents of Islam.

Adherents belong to one of two communities – Islamic Community of Serbia or the Islamic Community in Serbia.

Judaism

As of 2011, out of 787 declared Jews in Serbia 578 stated their religion as Judaism, mostly in the cities of Belgrade (286), Novi Sad (84), Subotica (75) and Pančevo (31).[5] The only remaining functioning synagogue in Serbia is the Belgrade Synagogue. There are also small numbers of Jews in Zrenjanin and Sombor, with isolated families scattered throughout the rest of Serbia.

Irreligion

About 1.1% of Serbian population is atheist. Religiosity was lowest in Novi Beograd, with 3.5% of population being atheists (compare to whole Belgrade's and Novi Sad's 1.5%) and highest in rural parts of the country, where atheism in most municipalities went below 0.01%.[7]

In a 2009 Gallup poll, 44% of respondents in Serbia answered 'no' to the question "Is religion an important part of your daily life?"[8]

A Pew Research Center poll, conducted from June 2015 to July 2016, found that 2% of Serbia were atheists, while 10% stated that they "Do not believe in God".[9]

Role of the religion in public life

Public schools allow religious teaching in cooperation with religious communities having agreements with the state, but attendance is not mandated. Religion classes (Serbian: verska nastava) are organized in public elementary and secondary schools, most commonly coordinated with the Serbian Orthodox Church, but also with the Catholic Church and Islamic community.

The public holidays in Serbia also include the religious festivals of Eastern Orthodox Christmas and Eastern Orthodox Easter, as well as Saint Sava Day which is a working holiday and is celebrated as a Day of Spirituality as well as Day of Education. Believers of other faiths are legally allowed to celebrate their religious holidays.

Religious freedom

The government of Serbia does not keep records of religiously motivated violence, and reporting from individual religious organization is sparse.[10]

The laws of Serbia establish the freedom of religion, forbid the establishment of a state religion, and outlaw religious discrimination. While registration with the government, is not necessary for religious groups to practice, the government confers certain privileges to registered groups. The government maintains a two-tiered system of registered groups, split between "traditional" groups and "nontraditional" groups. Minority groups and independent observers have complained that this system consists of religious discrimination.[10]

The government has programs established for the restitution of property confiscated by the government of Yugoslavia after World War II, and for property lost in the Holocaust.

The media and individual members of parliament have been criticized for using disparaging language when referring to non-traditional groups Antisemitic literature is commonly available in bookstores, and is prevalent online.[10]

Although religious freedom was largely respected by the government of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia[11][12] and the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia,[13] and Serbia's constitutions through its various incarnations as either an independent state or as part of Yugoslavia have nominally upheld religious freedom,[14] it was also the site of significant religiously and ethnically-motivated war crimes during World War II[15] and the Yugoslav Wars.[16]

See also

References

- http://pod2.stat.gov.rs/ObjavljenePublikacije/G2014/pdf/G20144012.pdf

- Demographic growth and ethnographic changes in Serbia

- Etnokonfesionalni i jezički mozaik Srbije, 2011 (PDF) (in Serbian). Belgrade: Republički zavod za statistiku. 2015. p. 181. Retrieved 8 February 2020.

- Book 3 Page 13 Archived 2011-04-24 at the Wayback Machine

- http://pod2.stat.gov.rs/ObjavljenePublikacije/Popis2011/Knjiga4_Veroispovest.pdf

- "Mapa verskih zajednica Novog Sada" (PDF). Ehons.org. Retrieved 2013-10-07.

- Book 3 Pages 13-16 Archived 2011-04-24 at the Wayback Machine

- "Gallup Global Reports". Gallup.com. Retrieved 2013-10-07.

- "Religious Belief and National Belonging in Central and Eastern Europe". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 10 May 2017. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- International Religious Freedom Report 2017 Serbia, US Department of State, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor.

- Romano, Jaša (1980). Jews of Yugoslavia 1941–1945. Federation of Jewish Communities of Yugoslavia. pp. 573–590.

- Rudolf B. Schlesinger (1988). Comparative law: cases, text, materials. Foundation Press. p. 328.

Some countries, notably the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, had preserved enclaves of Islamic law (relating to personal...)..

- Tomka, Miklós (2011). Expanding Religion: Religious Revival in Post-communist Central and Eastern Europe. Walter de Gruyter. p. 44. ISBN 9783110228151.

- International Religious Freedom Report 2017 Serbia, US Department of State, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor.

- Tomasevich, Jozo (2001). War and Revolution in Yugoslavia: 1941–1945. p744. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0804779244.

- United Nations Commission of Experts established pursuant to the United Nations Security Council Resolution 780 (1992) (28 December 1994). "Annex IV: The policy of ethnic cleansing". Final report. Archived from the original on 2 November 2010. Retrieved 28 October 2010.

Sources

- Kuburić, Z., 2010. Verske zajednice u Srbiji i verska distanca. CEIR—Centar za empirijska istraživanja religije.

- Radić, Radmila (2007). "Serbian Christianity". The Blackwell Companion to Eastern Christianity. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 231–248.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Radisavljević-Ćiparizović, D., 2002. Religija i svakodnevni život: vezanost ljudi za religiju i crkvu u Srbiji krajem devedesetih. Srbija krajem milenijuma: Razaranje društva, promene i svakodnevni život.

- Radulović, L.B., 2012. Religija ovde i sada: revitalizacije religije u Srbiji. Srpski geneaološki centar, Odeljenje za etnologiju i antropologiju Filozofskog fakulteta.

- Blagojević, M., 2011. „Aktuelna religioznost građana Srbije “, u A. Mladenović (prir.). Religioznost u Srbiji 2010, pp. 43–72.

- Đorđević, D.B., 2005. Religije i veroispovesti nacionalnih manjina u Srbiji. Sociologija, 47(3), pp. 193–212.

- Đukić, V., 2008. Religije Srbije–mreža dijaloga i saradnje.

- Ilić, A., 2013. Odnos religije i društva u današnjoj Srbiji. Religija i Tolerancija, 1(3).

- Kuburić, Z. and Gavrilović, D., 2013. Verovanje i pripadanje u savremenoj Srbiji. Religija i Tolerancija, (1).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Religion in Serbia. |