Red-eared slider

The red-eared slider (Trachemys scripta elegans), also known as the red-eared terrapin, red-eared slider turtle, red-eared turtle, slider turtle, and water slider turtle, is a semiaquatic turtle belonging to the family Emydidae. It is a subspecies of the pond slider. It is the most popular pet turtle in the United States and is also popular as a pet across the rest of the world.[2] Because of this, they are the most commonly traded turtle in the world.[3] Red-eared sliders are native to the southern United States and northern Mexico, but have become established in other places because of pet releases, and have become an invasive species in many areas where they outcompete native species. The red-eared slider is included in the list of the world's 100 most invasive species[4] published by the IUCN.

| Red-eared slider | |

|---|---|

_(1865)_by_Karl_Bodmer.jpg) | |

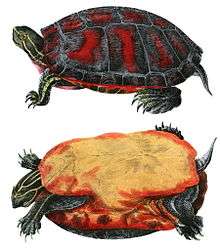

| Trachemys scripta elegans (Wied-Neuwied), an 1865 engraving by Karl Bodmer, who accompanied the authority on his expedition | |

| |

| At the Cincinnati Zoo | |

Domesticated | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Testudines |

| Suborder: | Cryptodira |

| Superfamily: | Testudinoidea |

| Family: | Emydidae |

| Genus: | Trachemys |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | T. s. elegans |

| Trinomial name | |

| Trachemys scripta elegans (Wied-Neuwied, 1839) | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

Name

The red-eared slider gets its name from the small red stripe around its ears and from its ability to slide quickly off rocks and logs into the water. This species was previously known as Troost's turtle in honor of an American herpetologist Gerard Troost. Trachemys scripta troostii is now the scientific name for another subspecies, the Cumberland slider.

Taxonomy

The red-eared slider belongs to the order Testudines which contains about 250 turtle species. It is a subspecies of Trachemys scripta. It was previously classified under the name Chrysemys scripta elegans.

The species Trachemys scripta contains three subspecies: T. s. elegans (red-eared slider), T. s. scripta (yellow-bellied slider), and T. s. troostii (Cumberland slider).[5]

Description

The carapace of this species can reach more than 40 cm (16 in) in length, but the average length ranges from 15 to 20 cm (6 to 8 in).[6] The females of the species are usually larger than the males. They typically live between 20 and 30 years, although some individuals have lived for more than 40 years.[7] Their life expectancy is shorter when they are kept in captivity.[8] The quality of their living environment has a strong influence on their lifespans and well being.

These turtles are poikilotherms, meaning they are unable to regulate their body temperatures independently; they are completely dependent on the temperature of their environment.[2] For this reason, they need to sunbathe frequently to warm themselves and maintain their body temperatures.

The shell is divided into two sections: the upper or dorsal carapace, and the lower, ventral carapace or plastron.[2] The upper carapace consists of the vertebral scutes, which form the central, elevated portion; pleural scutes that are located around the vertebral scutes; and then the marginal scutes around the edge of the carapace. The rear marginal scutes are notched. The scutes are bony keratinous elements. The carapace is oval and flattened (especially in the male) and has a weak keel that is more pronounced in the young.[9] The color of the carapace changes depending on the age of the turtle. The carapace usually has a dark green background with light and dark, highly variable markings. In young or recently hatched turtles, it is leaf green and gets slightly darker as a turtle gets older, until it is a very dark green, and then turns a shade between brown and olive green. The plastron is always a light yellow with dark, paired, irregular markings in the centre of most scutes. The plastron is highly variable in pattern. The head, legs, and tail are green with fine, irregular, yellow lines. The whole shell is covered in these stripes and markings that aid in camouflaging an individual.

These turtles also have a complete skeletal system, with partially webbed feet that help them to swim and that can be withdrawn inside the carapace along with the head and tail. The red stripe on each side of the head distinguishes the red-eared slider from all other North American species and gives this species its name, as the stripe is located behind the eyes where their (external) ears would be. These stripes may lose their color over time.[8] Some individuals can also have a small mark of the same color on the top of their heads. The red-eared slider does not have a visible outer ear or an external auditory canal; instead, it relies on a middle ear entirely covered by a cartilaginous tympanic disc.[10]

Sexual dimorphism

Some dimorphism exists between males and females.[11]

Red-eared slider young look practically identical regardless of their sex, making it difficult to distinguish them. One useful method, however, is to inspect the markings under their carapace, which fade as the turtles age. It is much easier to distinguish the sex of adults, as the shells of mature males are smaller than those of females.[12] Male red-eared sliders reach sexual maturity when their carapaces' diameters measure 10 cm (3.9 in) and females reach maturity when their carapaces measure 15 cm. Both male and females reach sexual maturity at five to six years. The male is normally smaller than the female, although this parameter is sometimes difficult to apply as individuals being compared could be of different ages.

Males have longer claws on their front feet than the females; this helps them to hold on to a female during mating and is used during courtship displays.[13] The male's tail is thicker and longer. Typically, the cloacal opening of the female is at or under the rear edge of the carapace, while the male's opening occurs beyond the edge of the carapace. The male's plastron is slightly concave, while that of the female is completely flat. The male's concave plastron also helps to stabilize the male on the female's carapace during mating.[14] Older males can sometimes have a dark greyish-olive green melanistic coloration, with very subdued markings. The red stripe on the sides of the head may be difficult to see or be absent. The female's appearance is substantially the same throughout her life.

Distribution and habitat

The red-eared slider originated from the area around the Mississippi River and the Gulf of Mexico, in warm climates in the southeastern United States. Their native areas range from the southeast of Colorado to Virginia and Florida. In nature, they inhabit areas with a source of still, warm water, such as ponds, lakes, swamps, creeks, streams, or slow-flowing rivers. They live in areas of calm water where they are able to leave the water easily by climbing onto rocks or tree trunks so they can warm up in the sun. Individuals are often found sunbathing in a group or even on top of each other. They also require abundant aquatic plants, as these are the adults' main food, although they are omnivores.[15] Turtles in the wild always remain close to water unless they are searching for a new habitat or when females leave the water to lay their eggs.

Owing to their popularity as pets, red-eared sliders have been released or escaped into the wild in many parts of the world.[16] The turtle is considered one of the world's worst invasive species.[17] Feral populations are now found in Australia, Europe, Great Britain, South Africa, the Caribbean Islands, Israel, Bahrain, the Mariana Islands, Guam, and southeast and far-east Asia.[18][19] In Australia, it is illegal for members of the public to import, keep, trade, or release red-eared sliders, as they are regarded as an invasive species[20]—see below. Their import has been banned by the European Union[21] as well as specific EU member countries.[22] In 2015 Japan announced it was planning to ban the import of red-eared sliders, but it would probably not take effect until 2020.[23] Invasive red-eared sliders cause negative impacts in the ecosystems they occupy because they have certain advantages over the native populations, such as a lower age at maturity, higher fecundity rates, and larger body size, which gives them a competitive advantage at basking and nesting sites, as well as when exploiting food resources.[24] They also transmit diseases and displace the other turtle species with which they compete for food and breeding space.[25]

Behavior

Red-eared sliders are almost entirely aquatic, but as they are cold-blooded, they leave the water to sunbathe to regulate their temperature.

Hibernation

Red-eared sliders do not hibernate, but actually brumate; while they become less active, they do occasionally rise to the surface for food or air. Brumation can occur to varying degrees. In the wild, red-eared sliders brumate over the winter at the bottoms of ponds or shallow lakes. They generally become inactive in October, when temperatures fall below 10 °C (50 °F).[9] During this time, the turtles enter a state of sopor, during which they do not eat or defecate, they remain nearly motionless, and the frequency of their breathing falls. Individuals usually brumate underwater, but they have also been found under banks and rocks, and in hollow stumps. In warmer winter climates, they can become active and come to the surface for basking. When the temperature begins to drop again, however, they quickly return to a brumation state. Sliders generally come up for food in early March to as late as the end of April.

During brumation, T. s. elegans can survive anaerobically for weeks, producing ATP from glycolysis. The turtle's metabolic rate drops dramatically, with heart rate and cardiac output dropping by 80% to minimise energy requirements.[26][27] The lactic acid produced is buffered by minerals in the shell, preventing acidosis.[28] Red-eared sliders kept captive indoors should not brumate.

Reproduction

Courtship and mating activities for red-eared sliders usually occur between March and July, and take place under water. During courtship, the male swims around the female and flutters or vibrates the back side of his long claws on and around her face and head, possibly to direct pheromones towards her.[29] The female swims toward the male and, if she is receptive, sinks to the bottom for mating. If the female is not receptive, she may become aggressive towards the male. Courtship can last 45 minutes, but mating takes only 10 minutes.[25]

On occasion, a male may appear to be courting another male, and when kept in captivity may also show this behaviour towards other household pets. Between male turtles, it could be a sign of dominance and may preclude a fight. Young turtles may carry out the courtship dance before they reach sexual maturity at five years of age, but they are unable to mate.[30]

After mating, the female spends extra time basking to keep her eggs warm.[30] She may also have a change of diet, eating only certain foods, or not eating as much as she normally would. A female can lay between two and 30 eggs depending on body size and other factors.[18] One female can lay up to five clutches in the same year, and clutches are usually spaced 12 to 36 days apart.[31] The time between mating and egg-laying can be days or weeks. The actual egg fertilization takes place during the egg-laying. This process also permits the laying of fertile eggs the following season, as the sperm can remain viable and available in the female's body in the absence of mating. During the last weeks of gestation, the female spends less time in the water and smells and scratches at the ground, indicating she is searching for a suitable place to lay her eggs. The female excavates a hole, using her hind legs, and lays her eggs in it.[32]

Incubation takes 59 to 112 days.[18] Late-season hatchlings may spend the winter in the nest and emerge when the weather warms in the spring. Just prior to hatching, the egg contains 50% turtle and 50% egg sac. A new hatchling breaks open its egg with its egg tooth, which falls out about an hour after hatching. This egg tooth never grows back. Hatchlings may stay inside their eggshells after hatching for the first day or two. If they are forced to leave the eggshell before they are ready, they will return if possible. When a hatchling decides to leave the shell, it still has a small sac protruding from its plastron. The yolk sac is vital and provides nourishment while visible, and several days later it will have been absorbed into the turtle's belly. The sac must be absorbed, and does not fall off. The split must heal on its own before the turtle is able to swim. The time between the egg hatching and water entry is 21 days.

Damage to or inordinate motion of the protruding egg yolk, enough to allow air into the turtle's body, results in death. This is the main reason for marking the top of turtle eggs if their relocation is required for any reason. An egg turned upside down will eventually terminate the embryo's growth by the sac smothering the embryo. If it manages to reach term, the turtle will try to flip over with the yolk sac, which would allow air into the body cavity and cause death. The other fatal danger is water getting into the body cavity before the sac is absorbed completely and while the opening has not completely healed yet.

The sex of red-eared sliders is determined by the incubation temperature during critical phases of the embryos' development. Only males are produced when eggs are incubated at temperatures of 22–27 °C (72–81 °F), whereas females develop at warmer temperatures.[33] Colder temperatures result in the death of the embryos.

As pets, invasive species, and human infection risk

Red-eared slider turtles are the world's most commonly traded reptile, due to their relatively low price, and usually low food price, small size and easy maintenance.[34][35] As with other turtles, tortoises, and box turtles, individuals that survive their first year or two can be expected to live generally around 30 years. They present an infection risk; particularly of Salmonella. This risk can be mitigated and minimized by changing the aquarium water at least once per two weeks for teenagers and once per week for babies or use a proper Aquarium water filter system. To protect oneself from infection wash hands whenever handling a red-eared slider or the water they dwell in. When they mature they can inflict painful bites, leading irresponsible owners to release them into the wild with negative ecological, social and, economic impacts.[36]

Infection risks and United States federal regulations on commercial distribution

Reptiles are asymptomatic (meaning they suffer no adverse side effects) carriers of bacteria of the genus Salmonella.[37] This has given rise to justifiable concerns given the many instances of infection of humans caused by the handling of turtles,[38] which has led to restrictions in the sale of red-eared sliders in the USA. A 1975 U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulation bans the sale (for general commercial and public use) of both turtle eggs and turtles with a carapace length of less than 4 in (10 cm). This regulation comes under the Public Health Service Act, and is enforced by the FDA in cooperation with state and local health jurisdictions. The ban was enacted because of the public health impact of turtle-associated salmonellosis. Turtles and turtle eggs found to be offered for sale in violation of this provision are subject to destruction in accordance with FDA procedures. A fine of up to $1,001 and/or imprisonment for up to one year is the penalty for those who refuse to comply with a valid final demand for destruction of such turtles or their eggs.[39] Many stores and flea markets still sell small turtles due to an exception in the FDA regulation which allows turtles under 4 in (10 cm) to be sold "for bona fide scientific, educational, or exhibition purposes, other than use as pets."[40] As with many other animals and inanimate objects, the risk of Salmonella exposure can be reduced by following basic rules of cleanliness. Small children must be taught to wash their hands immediately after they finish playing with the turtle, feeding it, or changing its water.

US state law

Some states have other laws and regulations regarding possession of red-eared sliders because they can be an invasive species where they are not native and have been introduced through the pet trade. Now, it is illegal in Florida to sell any wild-type red-eared slider, as they interbreed with the local yellow-bellied slider population — Trachemys scripta scripta is another subspecies of pond sliders, and hybrids typically combine the markings of the two subspecies. However, unusual color varieties such as albino and pastel red-eared sliders, which are derived from captive breeding, are still allowed for sale.[41]

An invasive species in Australia

In Australia, breeding populations have been found in New South Wales and Queensland, and individual turtles have been found in the wild in Victoria, the Australian Capital Territory and Western Australia.[42]

Red-eared slider turtles are considered a significant threat to native turtle species – they mature more quickly, grow larger, produce more offspring and are more aggressive.[42] Numerous studies provide evidence that red-eared slider turtles can out-compete native turtles for food and nesting and basking sites.[43] Because red-eared slider turtles eat plants as well as animals, they could also have a negative impact on a range of native aquatic species, including rare frogs.[44] There is also a significant risk that red-eared slider turtles will transfer diseases and parasites to native reptile species. There is evidence that a malaria-like parasite was spread to two wild turtle populations in Lane Cove River, Sydney.[45]

Social and economic costs are also likely to be substantial. The Queensland government has invested close to $1 million AUD in eradication programs to date.[42] As outlined in the foregoing section, the turtle may also have significant public health costs due to the impacts of turtle-associated salmonella on human health. Outbreaks in multiple states and fatalities in children, associated with handling salmonella-infected turtles, have been recorded in the USA.[46] Salmonella can also spread to humans when turtles contaminate drinking water.[47]

There have been varying degrees of action by state governments to date, ranging from ongoing eradication efforts by the Queensland government to very little action by the government of New South Wales.[48] Experts have ranked the species as high priority for management in Australia and are calling for a national prevention and eradication strategy, including a concerted education and compliance program to stop the illegal trade, possession and release of slider turtles.[49]

In popular culture

Within the second volume of the Tales of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, the popular comic book heroes were revealed as specimens of the red-eared slider. The popularity of the Turtles led to a craze for keeping them as pets in Great Britain, and subsequent ecological havoc as turtles were accidentally or deliberately released into the wild.[50]

See also

References

- Fritz Uwe; Peter Havaš (2007). "Checklist of Chelonians of the World" (PDF). Vertebrate Zoology. 57 (2): 207–208. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-05-01. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

- Boylan Sánchez Efrén. "Las Tortugas". Ed. Antártida. Archived from the original on 20 June 2008. Retrieved 20 July 2007.

- "Acuario de Veracruz". Archived from the original on 4 July 2007. Retrieved 21 July 2007.

- Lowe S., Browne M., Boudjelas S. (2000). 100 of the World’s Worst Invasive Alien Species. A Selection From the Global Invasive Species Database. IUCN/SSC Invasive Species Specialist Group (ISSG), Auckland, New Zealand.

- Win Kirkpatrick, Amanda Page & Marion Massam (November 2007). Pond Slider (Trachemys scripta) risk assessments for Australia (PDF). Department of Agriculture and Food, Western Australia.

- "Tortugas: La Tortuga de Florida". Retrieved 21 July 2007.

- "Tortuga de orejas rojas". Archived from the original on October 27, 2007. Retrieved 21 July 2007.

- "Tortuga de Orejas Rojas". Archived from the original on 11 July 2007. Retrieved 21 July 2007.

- Rodríguez Garrido María del Carmen. "Tortugas en Estanques de jardín". Retrieved 21 July 2007.

- Jakob Christensen-Dalsgaard, Christian Brandt, Katie L. Willis, Christian Bech Christensen, Darlene Ketten, Peggy Edds-Walton, Richard R. Fay, Peter T. Madsen and Catherine E. Carr (2012). "Specialization for underwater hearing by the tympanic middle ear of the turtle, Trachemys scripta elegans". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 279 (1739): 2816–2824. doi:10.1098/rspb.2012.0290. PMC 3367789. PMID 22438494.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Animal Diversity Web: Tachemys scripta". Animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu. Retrieved 2010-03-16.

- J Whitfield Gibbons & Jeffery E Lovich (1990). "Sexual Dimorphism in Turtles with Emphasis on the Slider Turtle (Trachemys scripta)" (PDF). Herpetological Monographs. 4: 1–29. doi:10.2307/1466966. JSTOR 1466966. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-11-05.

- H Mohan-Gibbons & T Norton (2010). "Turtles, tortoises and terrapins". In V V Tynes (ed.). Behaviour of Exotic Pets. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8138-0078-3.

- DP O’Rourke and J Schumacher (2002). "Biology and Diseases of Reptiles". In James G. Fox; Lynn C. Anderson; Franklin M. Loew; Fred W. Quimby (eds.). Laboratory Animal Medicine. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-263951-7.

- "Red-eared slider Turtle". Encyclopaedia of North American Reptiles and Amphibians. Mobile Reference. 2009-12-15. ISBN 978-1605014593.

- "SCOTLAND | Turtle mania causes welfare headache". BBC News. 2000-04-07. Retrieved 2009-02-28.

- Lowe S., Browne M., Boudjelas S., De Poorter M. (2000). 100 of the World’s Worst Invasive Alien Species. A selection from the Global Invasive Species Database. Published by The Invasive Species Specialist Group (ISSG) a specialist group of the Species Survival Commission (SSC) of the World Conservation Union (IUCN), Updated and reprinted version: November 2004. http://www.issg.org/pdf/publications/worst_100/english_100_worst.pdf, retrieved 2017-05-29

- Scalera, Riccardo. "Trachemys scripta" (PDF). Delivering Alien Invasive Species Inventories for Europe. Europe Aliens. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- Heidy Kikillus, K.; Hare, K. M.; Hartley, S. (2010-12-01). "Minimizing false-negatives when predicting the potential distribution of an invasive species: a bioclimatic envelope for the red-eared slider at global and regional scales". Animal Conservation. 13: 5–15. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1795.2008.00299.x. ISSN 1469-1795.

- "Red-eared slider" (PDF). Animal Pest Alert. 6. 2009.

- "Species listed in the Annexes of the EU Wildlife Trade Regulations". European Commission Environment. 16 September 2013. Retrieved 27 September 2013.

- Capdevila Argüelles Laura; Ángela Iglesias García; Jorge F. Orueta; Bernardo Zilletti. "Lista negra preliminar de EEI para España" (PDF). Especies Exóticas Invasoras: Diagnóstico y bases para la prevención y el manejo. Madrid: Organismo Autónomo Parques Nacionales. Ministerio De Medio Ambiente. ISBN 978-84-8014-667-8.

- Japan to ban imports of red-eared slider turtles July 30, 2015 The Japan Times Retrieved March 26, 2016

- B Parry. "The red-eared slider and hickatee on Grand Cayman". British Chelonia Group. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- Pendlebury, Paul; Bringsøe, H.; Pendelbury, Paul (2006). "NOBANIS — Invasive Alien Species Fact Sheet — Trachemys scripta". Global Invasive Species Database. IUCN/SSC Invasive Species Specialist Group (ISSG). Retrieved 17 August 2009.

- Hicks, J. M.; Farrell, A. P. (2000). "The cardiovascular responses of the red-eared slider (Trachemys scripta) acclimated to either 22 or 5 degrees C. I. Effects of anoxic exposure on in vivo cardiac performance". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 203 (Pt 24): 3765–3774. PMID 11076774.

- Hicks, J. M.; Farrell, A. P. (2000). "The cardiovascular responses of the red-eared slider (Trachemys scripta) acclimated to either 22 or 5 degrees C. II. Effects of anoxia on adrenergic and cholinergic control". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 203 (Pt 24): 3775–3784. PMID 11076740.

- Krivoruchko, A.; Storey, K. B. (2010). "Forever Young: Mechanisms of Natural Anoxia Tolerance and Potential Links to Longevity". Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. 3 (3): 186–198. doi:10.4161/oxim.3.3.12356. PMC 2952077. PMID 20716943.

- J Chitty & A Raftery (2013). "Biology". Essentials of Tortoise Medicine and Surgery. Wiley Blackwell. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-4051-9544-7.

- "Reproducción". Archived from the original on 25 December 2012. Retrieved 21 July 2007.

- "Trachemys scripta; Turtles of the World by Ernst, et al". Nlbif.eti.uva.nl. Archived from the original on 2012-03-15. Retrieved 2010-03-16.

- Loza V. Antonio. "Trachemys scripta elegans (Tortuga de orejas rojas)". Archived from the original on 17 July 2007. Retrieved 21 July 2007.

- Washington NatureMapping Program, Animal Facts: Red-eared Slider. Retrieved: 2012-11-13.

- Csurhes S, Hankamer C. 2012. Red-eared slider turtle. Invasive species risk assessment. Queensland Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry

- "Turtle Source's Slider Guide — Introduction — Is a slider right for you?". Turtlesource.webs.com. Archived from the original on 2009-12-06. Retrieved 2009-12-06.

- Csurhes S, Hankamer C. (2012). "Red-eared slider turtle." Invasive species risk assessment. Queensland Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry.

- Iglesias Isabel. "Tortuga de orejas rojas". Retrieved 21 July 2007.

- Multistate Outbreak of Human Salmonella Infections Associated with Exposure to Turtles

- GCTTS FAQ: "4 Inch Law", actually an FDA regulation

- Turtles intrastate and interstate requirements; FDA Regulation, Sec. 1240.62, page 678 part d1.

- Turtle ban begins today; New state law, newszap.com, 2007-07-01. Retrieved 2007-07-06.

- Csurhes S, Hankamer C. (2012, updated 2016). "Red-eared slider turtle" Invasive animal risk assessment; Biosecurity Queensland, Queensland Government, https://www.daf.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/76836/IPA-Red-Eared-Slider-Turtle-Risk-Assessment.pdf; retrieved 2017-05-29

- For example, see Polo-Cavia, N, López, P and Martín, J (2010). "Competitive interactions during basking between native and invasive freshwater turtle species" Biological Invasions 12(7):2141–2152.

- O’Keefe, S. (2005). "Investing in conjecture: Eradicating the red-eared slider in Queensland" 13th Australasian Vertebrate Pest Conference, Wellington, New Zealand

- Department of Agriculture and Food (2009). "Red-eared slider animal pest alert no. 6/2009" Department of Agriculture and Food, Western Australia.Social and economic impacts

- Center for Disease Control (2007). "Turtle associated salmonellosis in humans—United States 2006–2007, Center for Disease Control" MMWR Weekly 56(26):649–652.

- Bomford, M (2008). "Risk assessment models for establishment of exotic vertebrates in Australia and New Zealand" Invasive Animals Cooperative Research Centre, Canberra.

- Invasive Species Council (2014). "Biosecurity Failures in Australia: Red-eared slider turtles" https://invasives.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Biosecurity-failures-red-eared-slider-turtles.pdf. Retrieved 2017-05-29

- For example see, Massam, M, Kirkpatrick, W & Page, A (2010). "Assessment and prioritisation of risk for forty introduced animal species" Invasive Animals Cooperative Research Centre, Canberra; and Invasive Species Council; 2014; Biosecurity Failures in Australia: Red-eared slider turtles; https://invasives.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Biosecurity-failures-red-eared-slider-turtles.pdf. Retrieved 2017-05-29).

- "ENGLAND | 'Hero Turtle' craze leads to duck deaths". BBC News. 2001-11-16. Retrieved 2009-02-28.

Further reading

- Rachel M. Bowden: "A Modified Yolk Biopsy Technique improves survivorship of turtle eggs". Cal State East Bay Press Sep./Oct. 2009, ISSN 1522-2152 pp. 611–615 (online copy, p. 216, at Google Books)

- Carl H. Ernst, Jeffrey E. Lovich: Turtles of the United States and Canada. Johns Hopkins University Press 2009, ISBN 978-0-8018-9121-2, pp. 444–470 (online copy, p. 444, at Google Books)

- James H. Harding: Amphibians and Reptiles of the Great Lakes Region. University of Michigan Press 1997, ISBN 0-472-06628-5, pp. 216–220 (online copy, p. 216, at Google Books)

- John B. Jensen, Carlos D. Camp, Whit Gibbons: Amphibians and Reptiles of Georgia. University of Georgia Press 2008, ISBN 978-0-8203-3111-9, pp. 500–502 (online copy, p. 500, at Google Books)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Trachemys_scripta_elegans. |

- Discovery Channel's Animal Planet: Red-eared slider

- Exotic pets: Information on aquatic turtles & tortoises including a few articles specific to red-eared sliders

- Gulf Coast Turtle & Tortoise Society: Natural History: Red-eared slider

- RedEarSider.com, a site about caring for turtles in captivity

- Species Profile - Red-Eared Slider (Trachemys scripta elegans ), National Invasive Species Information Center, United States National Agricultural Library.