Diamondback terrapin

The diamondback terrapin or simply terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin) is a species of turtle native to the brackish coastal tidal marshes of the eastern and southern United States, and in Bermuda.[5] It belongs to the monotypic genus Malaclemys. It has one of the largest ranges of all turtles in North America, stretching as far south as the Florida Keys and as far north as Cape Cod.[6]

| Diamondback terrapin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photographed in the wild | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Testudines |

| Suborder: | Cryptodira |

| Superfamily: | Testudinoidea |

| Family: | Emydidae |

| Genus: | Malaclemys Gray, 1844 [2] |

| Species: | M. terrapin |

| Binomial name | |

| Malaclemys terrapin | |

| Synonyms[3][4] | |

|

List

| |

The name "terrapin" is derived from the Algonquian word torope.[7] It applies to Malaclemys terrapin in both British English and American English. The name originally was used by early European settlers in North America to describe these brackish-water turtles that inhabited neither freshwater habitats nor the sea. It retains this primary meaning in American English.[7] In British English, however, other semi-aquatic turtle species, such as the red-eared slider, might also be called terrapins..

Description

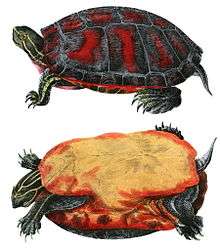

The common name refers to the diamond pattern on top of its shell (carapace), but the overall pattern and coloration vary greatly. The shell is usually wider at the back than in the front, and from above it appears wedge-shaped. The shell coloring can vary from brown to grey, and its body color can be grey, brown, yellow, or white. All have a unique pattern of wiggly, black markings or spots on their body and head. The diamondback terrapin has large webbed feet.[8] The species is sexually dimorphic in that the males grow to a carapace length of approximately 13 cm (5.1 in), while the females grow to an average carapace length of around 19 cm (7.5 in), though they are capable of growing larger. The largest female on record was just over 23 cm (9.1 in) in carapace length. Specimens from regions that are consistently warmer in temperature tend to be larger than those from cooler, more northern areas.[9] Male diamondback terrapins weigh 300 g (11 oz) on average, while females weigh around 500 g (18 oz).[10] The largest females can weigh up to 1,000 g (35 oz).[11]

Adaptations to their environment

Terrapins look much like their freshwater relatives, but are well adapted to the near shore marine environment. They have several adaptations that allow them to survive in varying salinities; they can live in full strength salt water for extended periods of time[12] and their skin is largely impermeable to salt. Terrapins have lachrymal salt glands,[13][14]not present in their relatives, which are used primarily when the turtle is dehydrated. They can distinguish between drinking water of different salinities.[15]Terrapins also exhibit unusual and sophisticated behavior to obtain fresh water, including drinking the freshwater surface layer that can accumulate on top of salt water during rainfall and raising their heads into the air with mouths open to catch falling rain drops.[15][16]

Terrapins are strong swimmers. They have strongly webbed hind feet, but not flippers as do sea turtles. Like their relatives (Graptemys), they have strong jaws for crushing shells of prey, such as clams and snails. This is especially true of females, who have larger and more muscular jaws than males.[17]

Subspecies

Seven subspecies are recognized, including the nominate race.

- M. t. centrata (Latreille, 1801) – Carolina diamondback terrapin (Georgia, Florida, North Carolina, South Carolina)[2]

- M. t. littoralis (Hay, 1904) – Texas diamondback terrapin (Texas)[2]

- M. t. macrospilota (Hay, 1904) – ornate diamondback terrapin (Florida) [2]

- M. t. pileata (Wied, 1865) – Mississippi diamondback terrapin (Alabama, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, Texas)[2]

- M. t. rhizophorarum Fowler, 1906 – mangrove diamondback terrapin (Florida)[2]

- M. t. tequesta Schwartz, 1955 – East Florida diamondback terrapin (Florida)[2]

- M. t. terrapin (Schoepff, 1793) – northern diamondback terrapin (Alabama, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, Mississippi, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Texas, Virginia)[18][19]

The isolated Bermudan population, which arrived in Bermuda on its own rather than being introduced by humans, has not yet been officially assigned to a subspecies but, based on mtDNA, it is closely related to the population from the Carolinas.[5]

Distribution and habitat

Diamondback terrapins live in the very narrow strip of coastal habitats on the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts of the United States, from as far north as Cape Cod, Massachusetts, to the southern tip of Florida and around the Gulf Coast to Texas. In most of their range, terrapins live in Spartina marshes that are flooded at high tide, but in Florida they also live in mangrove swamps.[20]This turtle can survive in freshwater as well as full-strength ocean water, but adults prefer intermediate salinities. They have no competition from other turtles, although common snapping turtles do occasionally make use of salty marshes.[21]It is unclear why terrapins do not inhabit the upper reaches of rivers within their range, as in captivity they tolerate fresh water. It is possible they are limited by the distribution of their prey.[22]Terrapins live quite close to shore, unlike sea turtles, which wander far out to sea; however, a population of terrapins on Bermuda has been determined to be self-established rather than introduced by humans.[5]Terrapins tend to live in the same areas for most or all of their lives, and do not make long distance migrations.[23][24][25]

Life cycle

Adult diamondback terrapins mate in the early spring, and clutches of 4-22[26] eggs are laid in sand dunes in the early summer. They hatch in late summer or early fall. Maturity in males is reached in 2–3 years at around 4.5 inches (110 mm) in length; it takes longer for females: 6–7 years (8–10 years for northern diamondback terrapins) at a length of around 6.75 inches (171 mm).

Reproduction

Like all reptiles, terrapin fertilization occurs internally. Courtship has been seen in May and June, and is similar to that of the closely related red-eared slider (Trachemys scripta).[27] Female terrapins can mate with multiple males and store sperm for years,[28] resulting in some clutches of eggs with more than one father.

Like many turtles, terrapins have temperature dependent sex determination, meaning that the sex of hatchlings is the result of incubation temperature. Females can lay up to three clutches of eggs/year in the wild,[29] and up to five clutches/year in captivity.[30] It is not known how often they may skip reproduction, so true clutch frequency is unknown.

Females may wander considerable distances on land before nesting. Nests are usually laid in sand dunes or scrub vegetation near the ocean[31] in June and July, but nesting may start as early as late April in Florida.[32] Females will quickly abandon a nest attempt if they are disturbed while nesting. Clutch sizes vary latitudinally, with average clutch sizes as low as 5.8/eggs/clutch in southern Florida[33] to 10.9 in New York.[29] After covering the nest, terrapins quickly return to the ocean and do not return except to nest again.

The eggs usually hatch in 60–85 days, depending on the temperature and the depth of the nest. Hatchlings usually emerge from the nest in August and September, but may overwinter in the nest after hatching.[34] Hatchlings sometimes stay on land in the nesting areas in both fall and spring and they may remain terrestrial for much or all of the winter in some places.[32][35] Hatchling terrapins are freeze tolerant,[34] which may facilitate overwintering on land. Hatchlings have lower salt tolerance than adults and Gibbons et al.[23] provided strong evidence that one- and two-year-old terrapins use different habitats than do old individuals.

Growth rates, age of maturity, and maximum age are not well known for terrapins in the wild, but males reach sexual maturity before females because of their smaller adult size. In females at least, sexual maturity is dependent on size rather than age.[36] Estimations of age based on counts of growth rings on the shell are as yet untested, so it is not clear how to determine the ages of wild terrapins.

Seasonal activities

Because nesting is the only terrapin activity that occurs on land, most other aspects of terrapin behavior are poorly known. Limited data suggest that terrapins hibernate in the colder months in most of their range, in the mud of creeks and marshes.[37]

Diet

The diamondback terrapin typically feeds on fish, marine snails (especially the saltmarsh periwinkle),[38]clams, mussels and other mollusks.[39] At high densities the terrapin may eat enough invertebrates to have ecosystem-level effects, partially because periwinkles themselves can overgraze important marsh plants, such as cordgrass (Spartina alterniflora).[40] Gender and age can greatly affect the diet of the diamondback terrapin, males and juvenile females tend to have less diversity in their diet. Adult females, due to their powerful, defined jaw, will occasionally feed on crustaceans such as crabs and are more likely to consume hard-shelled mollusks.[41]

Conservation

Status

In the 1900s, the species was once considered a delicacy to eat and was hunted almost to extinction. The population also decreased due to the development of coastal areas, terrapins being susceptible to wounds from the propellers on motorboats. Another common cause of death is the trapping of the turtles in recreational crab traps, as the turtles are attracted to the same bait as the crabs. Due to these factors, the diamondback terrapin is listed as an endangered species in Rhode Island, a threatened species in Massachusetts and is considered a "species of concern" in Georgia, Delaware, Alabama, Louisiana, North Carolina, and Virginia. The diamondback terrapin is listed as a “high priority species” under the South Carolina Wildlife Action Plan. In New Jersey, it was recommended to be listed as a Species of Special Concern in 2001. In July 2016, the species was removed from the New Jersey game list and is now listed as non-game with no hunting season. In Connecticut, there is no open hunting season for this animal. However, it holds no federal conservation status.[citation needed]

Conservation status

The species is classified as Near Threatened by the IUCN due to decreasing population numbers in much of its range. There is limited protection for terrapins on a state-by-state level throughout its range; it is listed as Endangered in Rhode Island and Threatened in Massachusetts. The Diamondback Terrapin Working Group [42] deal with regional protection issues. There is no national protection except through the Lacey Act, and little international protection.

Diamondback terrapins are the only U.S. turtles that inhabit the brackish waters of estuaries, tidal creeks and salt marshes. With a historic range stretching from Massachusetts to Texas, terrapin populations have been severely depleted by land development and other human impacts along the Atlantic coast.

Earthwatch Institute, a global non-profit that teams volunteers with scientists to conduct important environmental research, supports a research program called "Tagging the Terrapins of the Jersey Shore." This program allows volunteers to explore the coastal sprawl of New Jersey's Ocean County on Barnegat Bay, one of the most extensive salt marsh ecosystems on the East Coast, in search of this ornate turtle. On this project, volunteers contribute to environmental sustainability in the face of rampant development. Veteran turtle scientists Dr. Hal Avery, Dr. Jim Spotila, Dr. Walter Bien and Dr. Ed Standora are overseeing this program and the viability of terrapin populations in the face of growing environmental change.[43]

Threats

The major threats to diamondback terrapins are all associated with humans and probably differ in different parts of their range. People tend to build their cities on ocean coasts near the mouths of large rivers and in doing so they have destroyed many of the huge marshes that terrapins inhabited.[44] Nationwide, probably >75% of the salt marshes where terrapins lived have been destroyed or altered. Currently, ocean level rise threatens the remainder.

Traps used to catch crabs, both commercially and privately, have commonly caught and drowned many diamondback terrapins,[23] which can result in male-biased populations, local population declines, and even extinctions.[24][45] When these traps are lost or abandoned (“ghost traps”), they can kill terrapins for many years. Terrapin-excluding devices are available to retrofit crab traps; these reduce the number of terrapins captured while having little or no impact on crab capture rates.[46][47] In some states (NJ, DE, MD), these devices are required by law.

Nests, hatchlings, and sometimes adults[48]are commonly eaten by raccoons, foxes, rats[29][49][50]and many species of birds, especially crows and gulls.[32][51]Density of these predators are often increased because of their association with humans. Predation rates can be extremely high; predation by raccoons on terrapin nests at Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge in New York varied from 92-100% each year from 1998–2008,[29] Burke unpubl. data).

Terrapins are killed by cars when nesting females cross roads[52] and mortality can be high enough to seriously affect populations.[53]Terrapins are still harvested for food in some states. Terrapins may be affected by pollutants such as metals and organic compounds,[54] but this has not been demonstrated in wild populations.

There is an active casual and professional pet trade in terrapins and it is unknown how many are removed from the wild for this purpose. Some people breed the species in captivity[55] and some color variants are considered especially desirable. In Europe, Malaclemys are widely kept as pets, as are many closely related species.

Relationship with humans

In Maryland, diamondback terrapins were so plentiful in the 18th century that slaves protested the excessive use of this food source as their main protein. Late in the 19th century, demand for turtle soup claimed a harvest of 89,150 pounds from Chesapeake Bay in one year. In 1899, terrapin was offered on the dinner menu of Delmonico's Restaurant in New York City as the third most expensive item on the already-expensive menu. A patron could request either Maryland or Baltimore terrapin at a price of $2.50 (equivalent to $75.46 in 2018). Although demand was high, over capture was so high by 1920, the harvest of terrapins reached only 823 pounds for the year.[56]

According to the FAA National Wildlife Strike Database, a total of 18 strikes between diamondback terrapins and civil aircraft were reported in the US from 1990 to 2007, none of which caused damage to the aircraft.[57] On July 8, 2009, flights at John F. Kennedy Airport in New York City were delayed for up to one and a half hours as 78 diamondback terrapins had invaded one of the runways. The turtles, which according to airport authorities were believed to have entered the runway in order to nest, were removed and released back into the wild.[58] A similar incident happened on June 29, 2011, when over 150 turtles crossed runway 4, closing the runway and disrupting air traffic. Those terrapins were also relocated safely.[59] The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey installed a turtle barrier along runway 4L at JFK to reduce the number of terrapins on the runway and encourage them to nest elsewhere.[60] Nevertheless, on June 26, 2014, 86 terrapins made it onto the same runway, as a high tide carried them over the barrier. Their population is controlled by the raccoon population; it has been shown that as the raccoons decrease in number, mating terrapins increase, leading to increased turtle activity at the airport.[61]

Many human activities threaten the safety of diamondback terrapins. The terrapins get caught and drown in crab nets that humans put out, are suffocated by pollution that humans greatly contribute to, and lose their marsh and estuarine habitats because of urban development.[62]

History as a delicacy

Part of the pleasure of eating terrapin when the fashion was at its height, however, was its outré, bizarre, even monstrous essential nature...Killing, cleaning, and preparing terrapin is not easy...

— Paul Freedman[63]

Diamondback terrapins were heavily harvested for food in colonial America and probably before that by Native Americans. Terrapins were so abundant and easily obtained that slaves and even the Continental Army ate large numbers of them.

In the 19th century, a dish called "Terrapin à la Maryland", a stew with cream and sherry, was a canonical element, along with canvasback duck, of the elegant and regional "Maryland Feast" menu, an "elite standard...that lasted for decades".[63]

By 1917, terrapins sold for as much as $5 each (equivalent to $95.66 in 2017).[49] Huge numbers of terrapins were harvested from marshes and marketed in cities. By the early 1900s, populations in the northern part of the range were severely depleted and the southern part was greatly reduced as well.[64] As early as 1902 the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries (which later became the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service) recognized that terrapin populations were declining and started building large research facilities, centered at the Beaufort, North Carolina Fisheries Laboratory, to investigate methods for captive breeding terrapins for food.[65]People tried (unsuccessfully) to establish them in many other locations, including San Francisco.[66]

Use as a symbol

Maryland named the diamondback terrapin its official state reptile in 1994. The University of Maryland, College Park has used the species as its nickname (the Maryland Terrapins) and mascot (Testudo) since 1933, and the school newspaper has been named The Diamondback since 1921. The athletic teams are often referred to as "Terps" for short.[67] The Baltimore baseball club entry in the Federal League during 1914 and 1915 was called the Baltimore Terrapins. The terrapin has also been a symbol of the Grateful Dead because of their song "Terrapin Station". Many images of the terrapin dancing with a tambourine appear on posters, T-shirts and other places in Grateful Dead memorabilia.

References

- Roosenburg, W.M.; Baker, P.J.; Burke, R.; Dorcas, M.E. & Wood, R.C. (2018). "Malaclemys terrapin". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T12695A507698. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-1.RLTS.T12695A507698.en.

- Rhodin, Anders G.J.; van Dijk, Peter Paul; Inverson, John B.; Shaffer, H. Bradley (2010-12-14). "Turtles of the world, 2010 update: Annotated checklist of taxonomy, synonymy, distribution and conservation status" (PDF). Chelonian Research Monographs. 5: 000.101.

- Malaclemys terrapin (SCHOEPFF, 1793) - The Reptile Database

- Fritz Uwe; Peter Havaš (2007). "Checklist of Chelonians of the World" (PDF). Vertebrate Zoology. 57 (2): 190–192. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 December 2010. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

- Parham, J.F.; Outerbridge, Monika. E.; Stuart, B.L.; Wingate, D.B.; Erlenkeuser, H.; Papenfuss, T.J. (2008). "Introduced delicacy or native species? A natural origin of Bermudian terrapins supported by fossil and genetic data". Biol. Lett. 4 (2): 216–219. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2007.0599. PMC 2429930. PMID 18270164.

- Seigel, Richard A. (1980). "Nesting Habits of Diamondback Terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin) on the Atlantic Coast of Florida". Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science. 83 (4): 239–246. doi:10.2307/3628414. JSTOR 3628414.

- "Terrapin" at m-w.com

- State of Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection. "Northern Diamondback Terrapin Malaclemys t. terrapin" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 June 2012. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

- Davenport, John (1992)."The Biology of the Diamondback Terrapin Malaclemys Terrapin (Latreille)" Archived 2009-10-17 at the Wayback Machine, Tetsudo, 3(4)

- http://www.dep.state.fl.us/coastal/sites/stmartins/pub/SMM_Terrapin_Report.pdf

- Brennessel, Barbara (2006). Diamonds in the marsh: a natural history of the diamondback terrapin - Barbara Brennessel - Google Boeken. ISBN 9781584655367. Retrieved 2013-04-22.

- Bentley, P.J.; Bretz, W.L.; Schmidt-Nielsen, K. (1967). "Osmoregulation in the diamondback terrapin, Malaclemys terrapin cetrata". Journal of Experimental Biology. 46: 161–167.

- Cowan, F.B.M. (1971). "The ultrastructure of the lachrymal "salt" gland and the Harderian gland in the euryhaline Malaclemys and some closely related stenohaline emydids". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 49 (5): 691–697. doi:10.1139/z71-108. PMID 5557904.

- Cowan, F. B. M. (1981). "Effects of salt loading in salt gland function in the euryhaline turtle, Malaclemys terrapin". Journal of Comparative Physiology. 145: 101–108. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.494.4703. doi:10.1007/bf00782600.

- Davenport, J.; Macedo, E. A. (1990). "Behavioral osmotic control in the euryhaline diamondback terrapin Malaclemys terrapin: responses to low salinity and rainfall". Journal of Zoology. 220 (3): 487–496. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1990.tb04320.x.

- Bels, V.L.; Davenport, J.; Renous, S. (1995). "Drinking and water expulsion in the diamondback terrapin Malaclemys terrapin". Journal of Zoology (London). 236: 483–497.

- Tucker, A. D.; Fitzsimmons, N. N.; Gibbons, J. W. (1995). "Resource partitioning by the estuarine turtle Malaclemys terrapin: trophic, spatial and temporal foraging constraints". Herpetologica. 51: 167–181.

- (Conant 1975)

- (Smith 1982)

- Hart, K. M.; McIvor, C. C. (2008). "Demography and Ecology of Mangrove Diamondback Terrapins in a Wilderness Area of Everglades National Park, Florida, USA". Copeia. 2008: 200–208. doi:10.1643/ce-06-161.

- Kinneary, J. J. (1993). "Salinity relations of Chelydra serpentina in a Long Island estuary". Journal of Herpetology. 27 (4): 441–446. doi:10.2307/1564834. JSTOR 1564834.

- Coker, R. E. 1906. The natural history and cultivation of the diamond-back terrapin with notes of other forms of turtles. North Carolina Geological Survey Bulletin. 14:1-67

- Gibbons, J. W.; Lovich, J. E.; Tucker, A. D.; Fitzsimmons, N. N.; Greene, J. L. (2001). "Demographic and ecological factors affecting conservation and management of diamondback terrapins (Malaclemys terrapin) in South Carolina". Chelonian Conservation and Biology. 4: 66–74.

- Tucker, A. D.; Gibbons, J. W.; Greene, J. L. (2001). "Estimates of adult survival and migration for diamondback terrapins: conservation insight from local extirpation within a metapopulation". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 79 (12): 2199–2209. doi:10.1139/z01-185.

- Hauswaldt, J. S.; Glen, T. C. (2005). "Population genetics of the diamondback terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin)". Molecular Ecology. 14 (3): 723–732. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294x.2005.02451.x.

- Brennessel, Barbara. "Diamonds in the Marsh," Hanover: University Press of New England, 2006

- Seigel, R.A. (1980). "Courtship and mating behavior of the diamondback terrapin, Malaclemys terrapin tequesta". Journal of Herpetology. 14 (4): 420–421. doi:10.2307/1563703. JSTOR 1563703.

- Barney, R.L. 1922. Further notes on the natural history and artificial propagation of the diamondback terrapin. U.S. Bureau of Fisheries. Economic Circular No. 5, rev. 91-111

- Feinberg, J. A.; Burke, R. L. (2003). "Nesting ecology and predation of diamondback terrapins, Malaclemys terrapin, at Gateway National Recreation Area, New York". Journal of Herpetology. 37 (3): 517–526. doi:10.1670/207-02a.

- Hildebrand, S. F. (1928). "Review of the experiments on artificial culture of the diamond-back terrapin". Bulletin of the United States Bureau of Fisheries. 45: 25–70.

- Roosenburg, W. M. (1994). "Nesting habitat requirements of the diamondback terrapin: a geographic comparison". Wetlands Journal. 6: 9–12.

- Butler, J. A.; Broadhurst, C.; Green, M.; Mullin, Z. (2004). "Nesting, nest predation and hatchling emergence of the Carolina diamondback terrapin, Malaclemys terrapin centrata, in Northeastern Florida". American Midland Naturalist. 152: 145–155. doi:10.1674/0003-0031(2004)152[0145:nnpahe]2.0.co;2.

- Baldwin, J.D., L.A. Latino, B.K. Mealey, G.M. Parks, and M.R.J. Forstner. 2005. "The diamondback terrapin in Florida Bay and the Florida Keys: Insights into Turtle Conservation and Ecology". Chapter 20 In: In: W. E. Meshaka, Jr., and K. J. Babbitt, eds. Amphibians and Reptiles: status and conservation in Florida. Krieger Publishing Company, Malabar, Florida

- Baker, P.J.; Costanzo, J.P.; Herlands, R.; Wood, R.C.; Lee, R.E.; Jr (2006). "Inoculative freezing promotes winter survival in hatchling diamondback terrapin, Malaclemys terrapin". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 84: 116–124. doi:10.1139/z05-183.

- Pilter, R (1985). "Malaclemys terrapin terrapin (Northern diamondback terrapin) Behavior". Herpetological Review. 16: 82.

- Hildebrand, S. F. (1932). "Growth of diamond-back terrapins: size attained, sex ratio and longevity". Zoologica. 9: 231–238.

- Yearicks, E. F.; Wood, R. C.; Johnson, W . S. (1981). "Hibernation of the northern diamondback terrapin, Malaclemys terrapin terrapin". Estuaries. 4 (1): 78–80. doi:10.2307/1351546. JSTOR 1351546.

- "Diamondback Terrapin North Carolina Wildlife Profiles" (PDF).

- "Diamondback Terrapin Malaclemys terrapin".

- "25 Years of Terrapin Conservation and Research".

- "Foraging ecology and habitat use of the northern diamondback terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin terrapin) in southern Chesapeake Bay" (PDF).

- Diamondback Terrapin Working Group

- "Earthwatch: Tagging the Terrapins of the Jersey Shore".

- Ner, S, and R.L. Burke. 2008. Direct and indirect effects of urbanization on Diamondback terrapins of New York City: Distribution and predation of terrapin nests in a human-modified estuary. J.C. Mitchell, R.E. Jung, and B. Bartholomew (eds.). Pp. 107-117 In: Urban Herpetology. Herpetological Conservation Vol. 3: Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles

- Dorcas, M. E.; Wilson, J. D.; Gibbons, J. W. (2007). "Crab trapping causes population decline and demographic changes in diamondback terrapins over two decades". Biological Conservation. 137 (3): 334–340. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2007.02.014.

- Guillory, V.; Prejean, P. (1998). "Effect of a terrapin excluder device on blue crab, Callinectes sapidus, trap catches". Marine Fisheries Review. 60: 38–40.

- Roosenburg, W.M. and J.P. Green. 2000. Impact of a bycatch reduction device on diamondback terrapin and blue crab capture in crab pots" Ecological Applications 10:882-889

- Seigel, R.A. (1980). "Predation by raccoons on diamondback terrapins, Malaclemys terrapin tequesta". Journal of Herpetology. 14 (1): 87–89. doi:10.2307/1563885. JSTOR 1563885.

- Hay, W.P. 1917. Artificial Propagation of the diamondback terrapin. Department of Commerce Bureau of Fisheries Economic Circular No. 5, revised. Pages 3-21

- Draud, M.; Bossert, M.; Zimnavoda, S. (2004). "Predation on hatchling and juvenile diamondback terrapins (Malaclemys terrapin) by the Norway rat (Rattus norvegicus)". Journal of Herpetology. 38 (3): 467–470. doi:10.1670/29-04n.

- Burger, J (1977). "Determinants of hatching success in diamondback terrapin, Malaclemys terrapin". American Midland Naturalist. 97 (2): 444–464. doi:10.2307/2425108. JSTOR 2425108.

- Szerlag, S.; McRobert, S.P. (2006). "Road occurrence and mortality of the northern diamondback terrapin". Applied Herpetology. 3: 27–37. doi:10.1163/157075406775247058.

- Avissar, N.G. (2006). "Changes in population structure of diamondback terrapins (Malaclemys terrapin terrapin) in a previously surveyed creek in southern New Jersey". Chelonian Conservation and Biology. 5: 154–159. doi:10.2744/1071-8443(2006)5[154:cipsod]2.0.co;2.

- Holliday, D. K; Elskus, A. A.; Roosenburg, W. M. (2009). "Impacts of multiple stressors on growth and metabolic rate of Malaclemys terrapin". Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry. 28 (2): 338–345. doi:10.1897/08-145.1. PMID 18788897.

- Szymanski, S (2005). "Experience with the raising, keeping, and breeding of the diamondback terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin macrospilota)". Radiata. 14: 3–12.

- "Turtletrack.org". Archived from the original on 2003-02-12. Retrieved 2007-03-31.

- FAA National Wildlife Strike Database Archived 2008-08-28 at the Wayback Machine

- Turtles Delay Flights at JFK at the New York Post website

- Mating turtles shut down runway at JFK at CNN.com

- Prendergast, Daniel (15 June 2013). "Shell of a save: JFK barriers to block runway turtles". New York Post. Retrieved 15 June 2013.

- Schweber, Nate (3 July 2014). "Studying What Lures Turtles to a Tarmac at Kennedy Airport". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- Conant, Therese, Diamondback Terrapin (PDF), Division of Conservation Education, N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission, retrieved October 20, 2011

- Paul Freedman, "Terrapin Monster", p. 51-64 of Dina Khapaeva, ed., Man-Eating Monsters: Anthropocentrism and Popular Culture, ISBN 9781787695283, p. 59

- Coker, R. E. 1931. The diamondback terrapin in North Carolina. In (ed) H. F. Taylor, Survey of Marine Fisheries of North Carolina. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, NC pp. 219-230

- Wolfe, Douglas A. 2000. A History of the Federal Biological Laboratory at Beaufort, North Carolina 1899-1999.

- Brown, P. R. (1971). "The story of California diamondbacks". Herpetology. 5: 37–38.

- "Maryland state reptile—diamondback terrapin". Maryland manual on-line: a guide to Maryland government. Maryland State Archives. March 8, 2010. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

Bibliography

- Conant, Roger (1975). A Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of Eastern and Central North America (2nd ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Smith, Hobart Muir; Brody, E.D. (1982). Reptiles of North America: A Guide to Field Identification. New York: Golden Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Diamondback terrapin. |

- Video of a diamondback terrapin in Ocean City, NJ, 20 June 2010

- Jonathan's Diamondback Terrapin World

- Malaclemys Gallery

- Species Malaclemys terrapin at The Reptile Database