Protostega

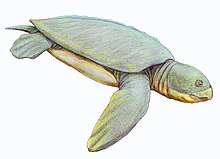

Protostega ('first roof')[1] is an extinct genus of sea turtle containing a single species, Protostega gigas. Its fossil remains have been found in the Smoky Hill Chalk formation of western Kansas (Hesperornis zone, dated to 83.5 million years ago[2]) and time-equivalent beds of the Mooreville Chalk Formation of Alabama.[3] Fossil specimens of this species were first collected in 1871, and named by Edward Drinker Cope in 1872.[4] With a length of 3 metres (9.8 ft), it is the second-largest sea turtle that ever lived, second only to the giant Archelon,[5] and the third-largest turtle of all time behind Archelon and Stupendemys.[6]

| Protostega | |

|---|---|

| |

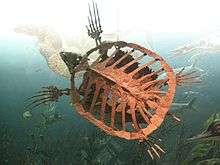

| Mounted skeleton | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Testudines |

| Suborder: | Cryptodira |

| Family: | †Protostegidae |

| Genus: | †Protostega Cope, 1872 |

| Type species | |

| †Protostega gigas Cope, 1872 | |

Discovery and History

The first known Protostega specimen (YPM 1408) was collected on July 4 by the 1871 Yale College Scientific Expedition, close to Fort Wallace and about 5 months before Cope arrived in Kansas. However the fossil that they found was never described or named.[7] It wasn't until E. D. Cope found and collected the first specimen of Protostega gigas in the Kansas chalk in 1871. A variety of bones were found in yellow cretaceous chalk from a bluff near Butte Creek.[8][9]

Paleoenvironment

The Late Cretaceous was marked by high temperatures, with large epicontinental seaways.[10] During the Mid-to Late Cretaceous period the Western Interior Seaway covered the majority of North America and would connect to the Boreal and Tethyan oceans at times.[11][12] Within these regions are where the fossil of Protostega gigas have been found.[13]

Description

Protostega is known to have reached up to 3 meters in length.[2] Cope' s Protostega gigas discovery reveled that their shell had a reduction of ossification that helped these huge animals with streamlining in the water and weight reduction.[14] The carapace was greatly reduced and the disk only extending less than half way towards the distal ends of the ribs. Cope described other greatly modified bones in his specimen including an extremely long coracoid process that reached all the way to the pelvis and a humerus that resembled a Dermochelys.[15]

[15] Creating better movement of their limbs.

Skull Structure: Edward Cope described the uniqued Protostega gigas to have a large jugal that reached to the quadrate along with a thickened pterygoid that reached to the mandibular articulating surface of the quadrate.[16] The fossil featured a reduction in the posterior portion of the vomer where the palatines meet medially.[16] Another fossilized specimen showed a bony extension, that would have been viewed as a beak, was lacking in the Protostega genus.[7] The premaxillary beak was very shorted then Archelon.[15] In front of the orbital region was elongated with broadly roofed temporal region. The jaws of the fossil showed a large crushing -surfaces.[15] The quadrato-jugal was triangular with a posterior edge that was concave and the entire bone was convex from distal view. The squamosal appeared to have a concave formation on the surface at the upper end of the quadrate. In Cope's fossil the mandible was preserved almost perfectly and from this he recorded that the jaw was very similar to the Chelonidae and the dentary had a broad for above downward with a concave surface, marked by deep pits in the dentary.[17]

Cope concluded that these animals were most likely omnivores and consumed a diet of hard shelled crustacean creatures, due to the long symphysis of its lower jaw.[15] Along with probably consisted of seaweed and jellyfish or scavenged on floating carcasses as well, like modern turtles.[18]

Classification

The classification of Protostega was complicated at best. The specimen that Cope discovered in Kansas was hard to evaluate with the preservation condition. The fossil shared many characteristics with two other recored genus named Dermochelys and Chelonidae. Cope wrote about the characteristics that distinctly separated this particular species from the two controversial groups. The differences he described were that the fossil had a reduced or lacking amount of dermal ossification on the back, the articulation of the pterygoid and quadrates, presplenial bone in the jaw was present, no articular process on the back side of the nuchal, simple formation of the radial process on the humerus and a peculiar bent formation of the xiphiplastra. He concluded that genus Protostega and species Protostega gigas was an intermediate form of the two groups Dermochelys and Chelonidae.[17]

See also

- List of Turtles

- Western Interior Seaway

- Late Cretaceous

References

- Hirayama, Ren (1994). "Phlogenetic systematics of cheloniod sea turtles". The Island Arc. 3 (4): 270–284. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1738.1994.tb00116.x.

- Carpenter, K. (2003). "Vertebrate Biostratigraphy of the Smoky Hill Chalk (Niobrara Formation) and the Sharon Springs Member (Pierre Shale)." High-Resolution Approaches in Stratigraphic Paleontology, 21: 421-437. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-9053-0

- Kiernan, Caitlin R. (2002). "Stratigraphic distribution and habitat segregation of mosasaurs in the Upper Cretaceous of western and central Alabama, with an historical review of Alabama mosasaur discoveries". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 22 (1): 91–103. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2002)022[0091:SDAHSO]2.0.CO;2.

- Cope, Edward Drinker (1872). "A description of the genus Protostega". Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia: 422–433.

- Lutz, Peter L.; John A. Musick (1996). The Biology of Sea Turtles. CRC PRess. p. 432pp. ISBN 0-8493-8422-2.

- Wood, R.C. (1976). "Stupendemys geographicus, the world's largest turtle." Breviora, 436: 1-31.

- "Protostega_dig-2011". oceansofkansas.com. Retrieved 2020-03-03.

- Cope, Edward (1871). "A Description of the Genus Protostega, a Form of Extinct Testudinata". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 12 (86): 422–433.

- Wiffen, J. (1981-03-01). "The first Late Cretaceous turtles from New Zealand". New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics. 24 (2): 293–299. doi:10.1080/00288306.1981.10422718. ISSN 0028-8306.

- Dennis, K. J.; Cochran, J. K.; Landman, N. H.; Schrag, D. P. (2013-01-15). "The climate of the Late Cretaceous: New insights from the application of the carbonate clumped isotope thermometer to Western Interior Seaway macrofossil". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 362: 51–65. Bibcode:2013E&PSL.362...51D. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2012.11.036. ISSN 0012-821X.

- Schröder-Adams, Claudia J.; Cumbaa, Stephen L.; Bloch, John; Leckie, Dale A.; Craig, Jim; Seif El-Dein, Safaa A.; Simons, Dirk-Jan H. A. E.; Kenig, Fabien (2001-06-15). "Late Cretaceous (Cenomanian to Campanian) paleoenvironmental history of the Eastern Canadian margin of the Western Interior Seaway: bonebeds and anoxic events". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 170 (3): 261–289. Bibcode:2001PPP...170..261S. doi:10.1016/S0031-0182(01)00259-0. ISSN 0031-0182.

- Petersen, Sierra V.; Tabor, Clay R.; Lohmann, Kyger C.; Poulsen, Christopher J.; Meyer, Kyle W.; Carpenter, Scott J.; Erickson, J. Mark; Matsunaga, Kelly K. S.; Smith, Selena Y.; Sheldon, Nathan D. (2016-11-01). "Temperature and salinity of the Late Cretaceous Western Interior Seaway". Geology. 44 (11): 903–906. Bibcode:2016Geo....44..903P. doi:10.1130/G38311.1. ISSN 0091-7613.

- "Mooreville Chalk", Wikipedia, 2019-12-16, retrieved 2020-03-04

- "Protostega gigas by Triebold Paleontology, Inc". trieboldpaleontology.com. Retrieved 2020-03-03.

- Carnegie Institution of Washington (1908). Carnegie Institution of Washington publication. MBLWHOI Library. Washington, Carnegie Institution of Washington.

- Hirayama, Ren (1994). "Phylogenetic systematics of chelonioid sea turtles". Island Arc. 3 (4): 270–284. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1738.1994.tb00116.x. ISSN 1440-1738.

- Case, Ermine Cowles (1897). On the Osteology and Relationships of Protostega. Ginn.

- "Marine Turtles". oceansofkansas.com. Retrieved 2020-03-03.