Proton

A proton is a subatomic particle, symbol

p

or

p+

, with a positive electric charge of +1e elementary charge and a mass slightly less than that of a neutron. Protons and neutrons, each with masses of approximately one atomic mass unit, are collectively referred to as "nucleons" (particles present in atomic nuclei).

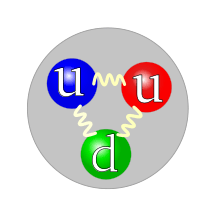

The quark content of a proton. The color assignment of individual quarks is arbitrary, but all three colors must be present. Forces between quarks are mediated by gluons. | |

| Classification | Baryon |

|---|---|

| Composition | 2 up quarks (u), 1 down quark (d) |

| Statistics | Fermionic |

| Interactions | Gravity, electromagnetic, weak, strong |

| Symbol | p , p+ , N+ , 1 1H+ |

| Antiparticle | Antiproton |

| Theorized | William Prout (1815) |

| Discovered | Observed as H+ by Eugen Goldstein (1886). Identified in other nuclei (and named) by Ernest Rutherford (1917–1920). |

| Mass | 1.67262192369(51)×10−27 kg[1] 1.007276466621(53) u[2] |

| Mean lifetime | > 2.1×1029 years (stable) |

| Electric charge | +1 e 1.602176634×10−19 C[2] |

| Charge radius | 0.8414(19) fm[2] |

| Electric dipole moment | < 5.4×10−24 e⋅cm |

| Electric polarizability | 1.20(6)×10−3 fm3 |

| Magnetic moment | 1.41060679736(60)×10−26 J⋅T−1[2] 2.79284734463(82) μN[2] |

| Magnetic polarizability | 1.9(5)×10−4 fm3 |

| Spin | 1/2 |

| Isospin | 1/2 |

| Parity | +1 |

| Condensed | I(JP) = 1/2(1/2+) |

One or more protons are present in the nucleus of every atom; they are a necessary part of the nucleus. The number of protons in the nucleus is the defining property of an element, and is referred to as the atomic number (represented by the symbol Z). Since each element has a unique number of protons, each element has its own unique atomic number.

The word proton is Greek for "first", and this name was given to the hydrogen nucleus by Ernest Rutherford in 1920. In previous years, Rutherford had discovered that the hydrogen nucleus (known to be the lightest nucleus) could be extracted from the nuclei of nitrogen by atomic collisions.[3] Protons were therefore a candidate to be a fundamental particle, and hence a building block of nitrogen and all other heavier atomic nuclei.

Although protons were originally considered fundamental or elementary particles, in the modern Standard Model of particle physics, protons are classified as hadrons, like neutrons, the other nucleon. Protons are composite particles composed of three valence quarks: two up quarks of charge +2/3e and one down quark of charge –1/3e. The rest masses of quarks contribute only about 1% of a proton's mass.[4] The remainder of a proton's mass is due to quantum chromodynamics binding energy, which includes the kinetic energy of the quarks and the energy of the gluon fields that bind the quarks together. Because protons are not fundamental particles, they possess a measurable size; the root mean square charge radius of a proton is about 0.84–0.87 fm (or 0.84×10−15 to 0.87×10−15 m).[5][6] In 2019, two different studies, using different techniques, have found the radius of the proton to be 0.833 fm, with an uncertainty of ±0.010 fm.[7][8]

At sufficiently low temperatures, free protons will bind to electrons. However, the character of such bound protons does not change, and they remain protons. A fast proton moving through matter will slow by interactions with electrons and nuclei, until it is captured by the electron cloud of an atom. The result is a protonated atom, which is a chemical compound of hydrogen. In vacuum, when free electrons are present, a sufficiently slow proton may pick up a single free electron, becoming a neutral hydrogen atom, which is chemically a free radical. Such "free hydrogen atoms" tend to react chemically with many other types of atoms at sufficiently low energies. When free hydrogen atoms react with each other, they form neutral hydrogen molecules (H2), which are the most common molecular component of molecular clouds in interstellar space.

Description

| Nuclear physics |

|---|

|

| Nucleus · Nucleons (p, n) · Nuclear matter · Nuclear force · Nuclear structure · Nuclear reaction |

|

Models of the nucleus |

|

Nuclear stability |

|

Alpha α · Beta β (2β, β+) · K/L capture · Isomeric (Gamma γ · Internal conversion) · Spontaneous fission · Cluster decay · Neutron emission · Proton emission |

|

High-energy processes |

|

Nuclear fusion Processes: Stellar · Big Bang · Supernova Nuclides: Primordial · Cosmogenic · Artificial |

|

Scientists Alvarez · Becquerel · Bethe · A. Bohr · N. Bohr · Chadwick · Cockcroft · Ir. Curie · Fr. Curie · Pi. Curie · Skłodowska-Curie · Davisson · Fermi · Hahn · Jensen · Lawrence · Mayer · Meitner · Oliphant · Oppenheimer · Proca · Purcell · Rabi · Rutherford · Soddy · Strassmann · Świątecki · Szilárd · Teller · Thomson · Walton · Wigner |

| Unsolved problem in physics: How do the quarks and gluons carry the spin of protons? (more unsolved problems in physics) |

Protons are spin-1/2 fermions and are composed of three valence quarks,[9] making them baryons (a sub-type of hadrons). The two up quarks and one down quark of a proton are held together by the strong force, mediated by gluons.[10]:21–22 A modern perspective has a proton composed of the valence quarks (up, up, down), the gluons, and transitory pairs of sea quarks. Protons have a positive charge distribution which decays approximately exponentially, with a mean square radius of about 0.8 fm.[11]

Protons and neutrons are both nucleons, which may be bound together by the nuclear force to form atomic nuclei. The nucleus of the most common isotope of the hydrogen atom (with the chemical symbol "H") is a lone proton. The nuclei of the heavy hydrogen isotopes deuterium and tritium contain one proton bound to one and two neutrons, respectively. All other types of atomic nuclei are composed of two or more protons and various numbers of neutrons.

History

The concept of a hydrogen-like particle as a constituent of other atoms was developed over a long period. As early as 1815, William Prout proposed that all atoms are composed of hydrogen atoms (which he called "protyles"), based on a simplistic interpretation of early values of atomic weights (see Prout's hypothesis), which was disproved when more accurate values were measured.[12]:39–42

In 1886, Eugen Goldstein discovered canal rays (also known as anode rays) and showed that they were positively charged particles (ions) produced from gases. However, since particles from different gases had different values of charge-to-mass ratio (e/m), they could not be identified with a single particle, unlike the negative electrons discovered by J. J. Thomson. Wilhelm Wien in 1898 identified the hydrogen ion as particle with highest charge-to-mass ratio in ionized gases.[13]

Following the discovery of the atomic nucleus by Ernest Rutherford in 1911, Antonius van den Broek proposed that the place of each element in the periodic table (its atomic number) is equal to its nuclear charge. This was confirmed experimentally by Henry Moseley in 1913 using X-ray spectra.

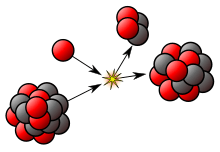

In 1917 (in experiments reported in 1919 and 1925), Rutherford proved that the hydrogen nucleus is present in other nuclei, a result usually described as the discovery of protons.[14] These experiments began after Rutherford had noticed that, when alpha particles were shot into air (mostly nitrogen), his scintillation detectors showed the signatures of typical hydrogen nuclei as a product. After experimentation Rutherford traced the reaction to the nitrogen in air and found that when alpha particles were introduced into pure nitrogen gas, the effect was larger. In 1919 Rutherford assumed that the alpha particle knocked a proton out of nitrogen, turning it into carbon. After observing Blackett's cloud chamber images in 1925, Rutherford realized that the opposite was the case: after capture of the alpha particle, a proton is ejected, so that heavy oxygen, not carbon, is the end result i.e. Z is not decremented but incremented. This was the first reported nuclear reaction, 14N + α → 17O + p. Depending on one's perspective, either 1919 or 1925 may be regarded as the moment when the proton was 'discovered'.

Rutherford knew hydrogen to be the simplest and lightest element and was influenced by Prout's hypothesis that hydrogen was the building block of all elements. Discovery that the hydrogen nucleus is present in all other nuclei as an elementary particle led Rutherford to give the hydrogen nucleus a special name as a particle, since he suspected that hydrogen, the lightest element, contained only one of these particles. He named this new fundamental building block of the nucleus the proton, after the neuter singular of the Greek word for "first", πρῶτον. However, Rutherford also had in mind the word protyle as used by Prout. Rutherford spoke at the British Association for the Advancement of Science at its Cardiff meeting beginning 24 August 1920.[15] Rutherford was asked by Oliver Lodge for a new name for the positive hydrogen nucleus to avoid confusion with the neutral hydrogen atom. He initially suggested both proton and prouton (after Prout).[16] Rutherford later reported that the meeting had accepted his suggestion that the hydrogen nucleus be named the "proton", following Prout's word "protyle".[17] The first use of the word "proton" in the scientific literature appeared in 1920.[18]

Recent research has shown that thunderstorms can produce protons with energies of up to several tens of MeV.[19][20]

Protons are routinely used for accelerators for proton therapy or various particle physics experiments, with the most powerful example being the Large Hadron Collider.

In a July 2017 paper, researchers measured the mass of a proton to be 1.007276466583+15

−29 atomic mass units (the values after the number being the statistical and systematic uncertainties, respectively), which is lower than measurements from the CODATA 2014 value by three standard deviations.[21][22]

Stability

| Unsolved problem in physics: Are protons fundamentally stable? Or do they decay with a finite lifetime as predicted by some extensions to the standard model? (more unsolved problems in physics) |

The free proton (a proton not bound to nucleons or electrons) is a stable particle that has not been observed to break down spontaneously to other particles. Free protons are found naturally in a number of situations in which energies or temperatures are high enough to separate them from electrons, for which they have some affinity. Free protons exist in plasmas in which temperatures are too high to allow them to combine with electrons. Free protons of high energy and velocity make up 90% of cosmic rays, which propagate in vacuum for interstellar distances. Free protons are emitted directly from atomic nuclei in some rare types of radioactive decay. Protons also result (along with electrons and antineutrinos) from the radioactive decay of free neutrons, which are unstable.

The spontaneous decay of free protons has never been observed, and protons are therefore considered stable particles according to the Standard Model. However, some grand unified theories (GUTs) of particle physics predict that proton decay should take place with lifetimes between 1031 to 1036 years and experimental searches have established lower bounds on the mean lifetime of a proton for various assumed decay products.[23][24][25]

Experiments at the Super-Kamiokande detector in Japan gave lower limits for proton mean lifetime of 6.6×1033 years for decay to an antimuon and a neutral pion, and 8.2×1033 years for decay to a positron and a neutral pion.[26] Another experiment at the Sudbury Neutrino Observatory in Canada searched for gamma rays resulting from residual nuclei resulting from the decay of a proton from oxygen-16. This experiment was designed to detect decay to any product, and established a lower limit to a proton lifetime of 2.1×1029 years.[27]

However, protons are known to transform into neutrons through the process of electron capture (also called inverse beta decay). For free protons, this process does not occur spontaneously but only when energy is supplied. The equation is:

The process is reversible; neutrons can convert back to protons through beta decay, a common form of radioactive decay. In fact, a free neutron decays this way, with a mean lifetime of about 15 minutes.

Quarks and the mass of a proton

In quantum chromodynamics, the modern theory of the nuclear force, most of the mass of protons and neutrons is explained by special relativity. The mass of a proton is about 80–100 times greater than the sum of the rest masses of the quarks that make it up, while the gluons have zero rest mass. The extra energy of the quarks and gluons in a region within a proton, as compared to the rest energy of the quarks alone in the QCD vacuum, accounts for almost 99% of the mass. The rest mass of a proton is, thus, the invariant mass of the system of moving quarks and gluons that make up the particle, and, in such systems, even the energy of massless particles is still measured as part of the rest mass of the system.

Two terms are used in referring to the mass of the quarks that make up protons: current quark mass refers to the mass of a quark by itself, while constituent quark mass refers to the current quark mass plus the mass of the gluon particle field surrounding the quark.[28]:285–286 [29]:150–151 These masses typically have very different values. As noted, most of a proton's mass comes from the gluons that bind the current quarks together, rather than from the quarks themselves. While gluons are inherently massless, they possess energy—to be more specific, quantum chromodynamics binding energy (QCBE)—and it is this that contributes so greatly to the overall mass of protons (see mass in special relativity). A proton has a mass of approximately 938 MeV/c2, of which the rest mass of its three valence quarks contributes only about 9.4 MeV/c2; much of the remainder can be attributed to the gluons' QCBE.[30][31][32]

The constituent quark model wavefunction for the proton is

The internal dynamics of protons are complicated, because they are determined by the quarks' exchanging gluons, and interacting with various vacuum condensates. Lattice QCD provides a way of calculating the mass of a proton directly from the theory to any accuracy, in principle. The most recent calculations[33][34] claim that the mass is determined to better than 4% accuracy, even to 1% accuracy (see Figure S5 in Dürr et al.[34]). These claims are still controversial, because the calculations cannot yet be done with quarks as light as they are in the real world. This means that the predictions are found by a process of extrapolation, which can introduce systematic errors.[35] It is hard to tell whether these errors are controlled properly, because the quantities that are compared to experiment are the masses of the hadrons, which are known in advance.

These recent calculations are performed by massive supercomputers, and, as noted by Boffi and Pasquini: "a detailed description of the nucleon structure is still missing because ... long-distance behavior requires a nonperturbative and/or numerical treatment..."[36] More conceptual approaches to the structure of protons are: the topological soliton approach originally due to Tony Skyrme and the more accurate AdS/QCD approach that extends it to include a string theory of gluons,[37] various QCD-inspired models like the bag model and the constituent quark model, which were popular in the 1980s, and the SVZ sum rules, which allow for rough approximate mass calculations.[38] These methods do not have the same accuracy as the more brute-force lattice QCD methods, at least not yet.

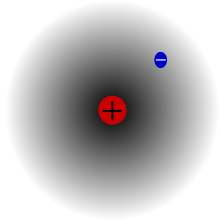

Charge radius

The problem of defining a radius for an atomic nucleus (proton) is similar to the problem of atomic radius, in that neither atoms nor their nuclei have definite boundaries. However, the nucleus can be modeled as a sphere of positive charge for the interpretation of electron scattering experiments: because there is no definite boundary to the nucleus, the electrons "see" a range of cross-sections, for which a mean can be taken. The qualification of "rms" (for "root mean square") arises because it is the nuclear cross-section, proportional to the square of the radius, which is determining for electron scattering.

The internationally accepted value of a proton's charge radius is 0.8768 fm (see orders of magnitude for comparison to other sizes). This value is based on measurements involving a proton and an electron (namely, electron scattering measurements and complex calculation involving scattering cross section based on Rosenbluth equation for momentum-transfer cross section), and studies of the atomic energy levels of hydrogen and deuterium.

However, in 2010 an international research team published a proton charge radius measurement via the Lamb shift in muonic hydrogen (an exotic atom made of a proton and a negatively charged muon). As a muon is 200 times heavier than an electron, its de Broglie wavelength is correspondingly shorter. This smaller atomic orbital is much more sensitive to the proton's charge radius, so allows more precise measurement. Their measurement of the root-mean-square charge radius of a proton is "0.84184(67) fm, which differs by 5.0 standard deviations from the CODATA value of 0.8768(69) fm".[39] In January 2013, an updated value for the charge radius of a proton—0.84087(39) fm—was published. The precision was improved by 1.7 times, increasing the significance of the discrepancy to 7σ.[6] The 2014 CODATA adjustment slightly reduced the recommended value for the proton radius (computed using electron measurements only) to 0.8751(61) fm, but this leaves the discrepancy at 5.6σ.

The international research team that obtained this result at the Paul Scherrer Institut in Villigen includes scientists from the Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, the Institut für Strahlwerkzeuge of Universität Stuttgart, and the University of Coimbra, Portugal.[40][41] The team is now attempting to explain the discrepancy, and re-examining the results of both previous high-precision measurements and complex calculations involving scattering cross section. If no errors are found in the measurements or calculations, it could be necessary to re-examine the world's most precise and best-tested fundamental theory: quantum electrodynamics.[40] The proton radius remains a puzzle as of 2017.[42] Perhaps the discrepancy is due to new physics, or the explanation may be an ordinary physics effect that has been missed.[43]

The radius is linked to the form factor and momentum transfer cross section. The atomic form factor G modifies the cross section corresponding to point-like proton.

The atomic form factor is related to the wave function density of the target:

The form factor can be split in electric and magnetic form factors. These can be further written as linear combinations of Dirac and Pauli form factors.[43]

Pressure inside the proton

Since the proton is composed of quarks confined by gluons, an equivalent pressure which acts on the quarks can be defined. This allows calculation of their distribution as a function of distance from the centre using Compton scattering of high-energy electrons (DVCS, for deeply virtual Compton scattering). The pressure is maximum at the centre, about 1035 Pa which is greater than the pressure inside a neutron star.[44] It is positive (repulsive) to a radial distance of about 0.6 fm, negative (attractive) at greater distances, and very weak beyond about 2 fm.

Charge radius in solvated proton, hydronium

The radius of hydrated proton appears in the Born equation for calculating the hydration enthalpy of hydronium.

Interaction of free protons with ordinary matter

Although protons have affinity for oppositely charged electrons, this is a relatively low-energy interaction and so free protons must lose sufficient velocity (and kinetic energy) in order to become closely associated and bound to electrons. High energy protons, in traversing ordinary matter, lose energy by collisions with atomic nuclei, and by ionization of atoms (removing electrons) until they are slowed sufficiently to be captured by the electron cloud in a normal atom.

However, in such an association with an electron, the character of the bound proton is not changed, and it remains a proton. The attraction of low-energy free protons to any electrons present in normal matter (such as the electrons in normal atoms) causes free protons to stop and to form a new chemical bond with an atom. Such a bond happens at any sufficiently "cold" temperature (i.e., comparable to temperatures at the surface of the Sun) and with any type of atom. Thus, in interaction with any type of normal (non-plasma) matter, low-velocity free protons are attracted to electrons in any atom or molecule with which they come in contact, causing the proton and molecule to combine. Such molecules are then said to be "protonated", and chemically they often, as a result, become so-called Brønsted acids.

Proton in chemistry

Atomic number

In chemistry, the number of protons in the nucleus of an atom is known as the atomic number, which determines the chemical element to which the atom belongs. For example, the atomic number of chlorine is 17; this means that each chlorine atom has 17 protons and that all atoms with 17 protons are chlorine atoms. The chemical properties of each atom are determined by the number of (negatively charged) electrons, which for neutral atoms is equal to the number of (positive) protons so that the total charge is zero. For example, a neutral chlorine atom has 17 protons and 17 electrons, whereas a Cl− anion has 17 protons and 18 electrons for a total charge of −1.

All atoms of a given element are not necessarily identical, however. The number of neutrons may vary to form different isotopes, and energy levels may differ, resulting in different nuclear isomers. For example, there are two stable isotopes of chlorine: 35

17Cl

with 35 − 17 = 18 neutrons and 37

17Cl

with 37 − 17 = 20 neutrons.

Hydrogen ion

) implies that that H-atom has lost its one electron, causing only a proton to remain. Thus, in chemistry, the terms "proton" and "hydrogen ion" (for the protium isotope) are used synonymously

Ross Stewart, The Proton: Application to Organic Chemistry (1985, p. 1)

In chemistry, the term proton refers to the hydrogen ion, H+

. Since the atomic number of hydrogen is 1, a hydrogen ion has no electrons and corresponds to a bare nucleus, consisting of a proton (and 0 neutrons for the most abundant isotope protium 1

1H

). The proton is a "bare charge" with only about 1/64,000 of the radius of a hydrogen atom, and so is extremely reactive chemically. The free proton, thus, has an extremely short lifetime in chemical systems such as liquids and it reacts immediately with the electron cloud of any available molecule. In aqueous solution, it forms the hydronium ion, H3O+, which in turn is further solvated by water molecules in clusters such as [H5O2]+ and [H9O4]+.[45]

The transfer of H+

in an acid–base reaction is usually referred to as "proton transfer". The acid is referred to as a proton donor and the base as a proton acceptor. Likewise, biochemical terms such as proton pump and proton channel refer to the movement of hydrated H+

ions.

The ion produced by removing the electron from a deuterium atom is known as a deuteron, not a proton. Likewise, removing an electron from a tritium atom produces a triton.

Proton nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR)

Also in chemistry, the term "proton NMR" refers to the observation of hydrogen-1 nuclei in (mostly organic) molecules by nuclear magnetic resonance. This method uses the spin of the proton, which has the value one-half (in units of hbar). The name refers to examination of protons as they occur in protium (hydrogen-1 atoms) in compounds, and does not imply that free protons exist in the compound being studied.

Human exposure

The Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Packages (ALSEP) determined that more than 95% of the particles in the solar wind are electrons and protons, in approximately equal numbers.[46][47]

Because the Solar Wind Spectrometer made continuous measurements, it was possible to measure how the Earth's magnetic field affects arriving solar wind particles. For about two-thirds of each orbit, the Moon is outside of the Earth's magnetic field. At these times, a typical proton density was 10 to 20 per cubic centimeter, with most protons having velocities between 400 and 650 kilometers per second. For about five days of each month, the Moon is inside the Earth's geomagnetic tail, and typically no solar wind particles were detectable. For the remainder of each lunar orbit, the Moon is in a transitional region known as the magnetosheath, where the Earth's magnetic field affects the solar wind, but does not completely exclude it. In this region, the particle flux is reduced, with typical proton velocities of 250 to 450 kilometers per second. During the lunar night, the spectrometer was shielded from the solar wind by the Moon and no solar wind particles were measured.[46]

Protons also have extrasolar origin from galactic cosmic rays, where they make up about 90% of the total particle flux. These protons often have higher energy than solar wind protons, and their intensity is far more uniform and less variable than protons coming from the Sun, the production of which is heavily affected by solar proton events such as coronal mass ejections.

Research has been performed on the dose-rate effects of protons, as typically found in space travel, on human health.[47][48] To be more specific, there are hopes to identify what specific chromosomes are damaged, and to define the damage, during cancer development from proton exposure.[47] Another study looks into determining "the effects of exposure to proton irradiation on neurochemical and behavioral endpoints, including dopaminergic functioning, amphetamine-induced conditioned taste aversion learning, and spatial learning and memory as measured by the Morris water maze.[48] Electrical charging of a spacecraft due to interplanetary proton bombardment has also been proposed for study.[49] There are many more studies that pertain to space travel, including galactic cosmic rays and their possible health effects, and solar proton event exposure.

The American Biostack and Soviet Biorack space travel experiments have demonstrated the severity of molecular damage induced by heavy ions on microorganisms including Artemia cysts.[50]

Antiproton

CPT-symmetry puts strong constraints on the relative properties of particles and antiparticles and, therefore, is open to stringent tests. For example, the charges of a proton and antiproton must sum to exactly zero. This equality has been tested to one part in 108. The equality of their masses has also been tested to better than one part in 108. By holding antiprotons in a Penning trap, the equality of the charge-to-mass ratio of protons and antiprotons has been tested to one part in 6×109.[51] The magnetic moment of antiprotons has been measured with error of 8×10−3 nuclear Bohr magnetons, and is found to be equal and opposite to that of a proton.

See also

- Fermion field

- Hydrogen

- Hydron (chemistry)

- List of particles

- Proton-proton chain reaction

- Quark model

- Proton spin crisis

References

- "2018 CODATA Value: proton mass". The NIST Reference on Constants, Units, and Uncertainty. NIST. 20 May 2019. Retrieved 2019-05-20.

- "2018 CODATA recommended values" https://physics.nist.gov/cuu/Constants/index.html

- "proton | Definition, Mass, Charge, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2018-10-20.

- Cho, Adrian (2 April 2010). "Mass of the Common Quark Finally Nailed Down". Science Magazine. American Association for the Advancement of Science. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- "Proton size puzzle reinforced!". Paul Shearer Institute. 25 January 2013.

- Antognini, Aldo; et al. (25 January 2013). "Proton Structure from the Measurement of 2S-2P Transition Frequencies of Muonic Hydrogen" (PDF). Science. 339 (6118): 417–420. Bibcode:2013Sci...339..417A. doi:10.1126/science.1230016. hdl:10316/79993. PMID 23349284. S2CID 346658.

- Bezginov, N.; Valdez, T.; Horbatsch, M.; Marsman, A.; Vutha, A. C.; Hessels, E. A. (2019-09-06). "A measurement of the atomic hydrogen Lamb shift and the proton charge radius". Science. 365 (6457): 1007–1012. Bibcode:2019Sci...365.1007B. doi:10.1126/science.aau7807. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 31488684. S2CID 201845158.

- Xiong, W.; Gasparian, A.; Gao, H.; Dutta, D.; Khandaker, M.; Liyanage, N.; Pasyuk, E.; Peng, C.; Bai, X.; Ye, L.; Gnanvo, K. (November 2019). "A small proton charge radius from an electron–proton scattering experiment". Nature. 575 (7781): 147–150. Bibcode:2019Natur.575..147X. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1721-2. ISSN 1476-4687. OSTI 1575200. PMID 31695211. S2CID 207831686.

- Adair, R. K. (1989). The Great Design: Particles, Fields, and Creation. Oxford University Press. p. 214. Bibcode:1988gdpf.book.....A.

- Cottingham, W. N.; Greenwood, D. A. (1986). An Introduction to Nuclear Physics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521657334.

- Basdevant, J.-L.; Rich, J.; Spiro, M. (2005). Fundamentals in Nuclear Physics. Springer. p. 155. ISBN 978-0-387-01672-6.

- Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry UCLA Eric R. Scerri Lecturer (2006-10-12). The Periodic Table : Its Story and Its Significance: Its Story and Its Significance. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-534567-4.

- Wien, Wilhelm (1904). "Über positive Elektronen und die Existenz hoher Atomgewichte". Annalen der Physik. 318 (4): 669–677. Bibcode:1904AnP...318..669W. doi:10.1002/andp.18943180404.

- Petrucci, R. H.; Harwood, W. S.; Herring, F. G. (2002). General Chemistry (8th ed.). Upper Saddle River, N.J. : Prentice Hall. p. 41.

- See meeting report and announcement

- Romer A (1997). "Proton or prouton? Rutherford and the depths of the atom". American Journal of Physics. 65 (8): 707. Bibcode:1997AmJPh..65..707R. doi:10.1119/1.18640.

- Rutherford reported acceptance by the British Association in a footnote to Masson, O. (1921). "XXIV. The constitution of atoms". Philosophical Magazine. Series 6. 41 (242): 281–285. doi:10.1080/14786442108636219.

- Pais, A. (1986). Inward Bound. Oxford University Press. p. 296. ISBN 0198519974. Pais believed the first science literature use of the word proton occurs in "Physics at the British Association". Nature. 106 (2663): 357–358. 1920. Bibcode:1920Natur.106..357.. doi:10.1038/106357a0.

- Köhn, C.; Ebert, U. (2015). "Calculation of beams of positrons, neutrons and protons associated with terrestrial gamma-ray flashes" (PDF). Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres. 23 (4): 1620–1635. Bibcode:2015JGRD..120.1620K. doi:10.1002/2014JD022229.

- Köhn, C.; Diniz, G.; Harakeh, Muhsin (2017). "Production mechanisms of leptons, photons, and hadrons and their possible feedback close to lightning leaders". Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres. 122 (2): 1365–1383. Bibcode:2017JGRD..122.1365K. doi:10.1002/2016JD025445. PMC 5349290. PMID 28357174.

- Popkin, Gabriel (20 July 2017). "Surprise! The proton is lighter than we thought". Science.

- Heiße, F.; Köhler-Langes, F.; Rau, S.; Hou, J.; Junck, S.; Kracke, A.; Mooser, A.; Quint, W.; Ulmer, S.; Werth, G.; Blaum, K.; Sturm, S. (18 July 2017). "High-Precision Measurement of the Proton's Atomic Mass". Physical Review Letters. 119 (3): 033001. arXiv:1706.06780. Bibcode:2017PhRvL.119c3001H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.119.033001. PMID 28777624. S2CID 31683973.

- Buccella, F.; Miele, G.; Rosa, L.; Santorelli, P.; Tuzi, T. (1989). "An upper limit for the proton lifetime in SO(10)". Physics Letters B. 233 (1–2): 178–182. Bibcode:1989PhLB..233..178B. doi:10.1016/0370-2693(89)90637-0.

- Lee, D.G.; Mohapatra, R.; Parida, M.; Rani, M. (1995). "Predictions for the proton lifetime in minimal nonsupersymmetric SO(10) models: An update". Physical Review D. 51 (1): 229–235. arXiv:hep-ph/9404238. Bibcode:1995PhRvD..51..229L. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.51.229. PMID 10018289.

- "Proton lifetime is longer than 1034 years". Kamioka Observatory. November 2009.

- Nishino, H.; et al. (2009). "Search for Proton Decay via p→e+π0 and p→μ+π0 in a Large Water Cherenkov Detector". Physical Review Letters. 102 (14): 141801. arXiv:0903.0676. Bibcode:2009PhRvL.102n1801N. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.141801. PMID 19392425. S2CID 32385768.

- Ahmed, S.; et al. (2004). "Constraints on Nucleon Decay via Invisible Modes from the Sudbury Neutrino Observatory". Physical Review Letters. 92 (10): 102004. arXiv:hep-ex/0310030. Bibcode:2004PhRvL..92j2004A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.92.102004. PMID 15089201. S2CID 119336775.

- Watson, A. (2004). The Quantum Quark. Cambridge University Press. pp. 285–286. ISBN 978-0-521-82907-6.

- Smith, Timothy Paul (2003). Hidden Worlds: Hunting for Quarks in Ordinary Matter. Princeton University Press. Bibcode:2003hwhq.book.....S. ISBN 978-0-691-05773-6.

- Weise, W.; Green, A. M. (1984). Quarks and Nuclei. World Scientific. pp. 65–66. ISBN 978-9971-966-61-4.

- Ball, Philip (Nov 20, 2008). "Nuclear masses calculated from scratch". Nature. doi:10.1038/news.2008.1246. Retrieved Aug 27, 2014.

- Reynolds, Mark (Apr 2009). "Calculating the Mass of a Proton". CNRS International Magazine (13). ISSN 2270-5317. Retrieved Aug 27, 2014.

- See this news report Archived 2009-04-16 at the Wayback Machine and links

- Durr, S.; Fodor, Z.; Frison, J.; Hoelbling, C.; Hoffmann, R.; Katz, S.D.; Krieg, S.; Kurth, T.; Lellouch, L.; Lippert, T.; Szabo, K.K.; Vulvert, G. (2008). "Ab Initio Determination of Light Hadron Masses". Science. 322 (5905): 1224–1227. arXiv:0906.3599. Bibcode:2008Sci...322.1224D. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.249.2858. doi:10.1126/science.1163233. PMID 19023076. S2CID 14225402.

- Perdrisat, C. F.; Punjabi, V.; Vanderhaeghen, M. (2007). "Nucleon electromagnetic form factors". Progress in Particle and Nuclear Physics. 59 (2): 694–764. arXiv:hep-ph/0612014. Bibcode:2007PrPNP..59..694P. doi:10.1016/j.ppnp.2007.05.001. S2CID 15894572.

- Boffi, Sigfrido; Pasquini, Barbara (2007). "Generalized parton distributions and the structure of the nucleon". Rivista del Nuovo Cimento. 30 (9): 387. arXiv:0711.2625. Bibcode:2007NCimR..30..387B. doi:10.1393/ncr/i2007-10025-7. S2CID 15688157.

- Joshua, Erlich (December 2008). "Recent Results in AdS/QCD". Proceedings, 8th Conference on Quark Confinement and the Hadron Spectrum, September 1–6, 2008, Mainz, Germany. arXiv:0812.4976. Bibcode:2008arXiv0812.4976E.

- Pietro, Colangelo; Alex, Khodjamirian (October 2000). "QCD Sum Rules, a Modern Perspective". In M., Shifman (ed.). At the Frontier of Particle Physics: Handbook of QCD. World Scientific Publishing. pp. 1495–1576. arXiv:hep-ph/0010175. Bibcode:2001afpp.book.1495C. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.346.9301. doi:10.1142/9789812810458_0033. ISBN 978-981-02-4445-3. S2CID 16053543.

- Pohl, Randolf; et al. (8 July 2010). "The size of the proton". Nature. 466 (7303): 213–216. Bibcode:2010Natur.466..213P. doi:10.1038/nature09250. PMID 20613837. S2CID 4424731.

- Researchers Observes Unexpectedly Small Proton Radius in a Precision Experiment. AZo Nano. July 9, 2010

- "The Proton Just Got Smaller". Photonics.Com. 12 July 2010. Retrieved 2010-07-19.

- Conover, Emily (2017-04-18). "There's still a lot we don't know about the proton". Science News. Retrieved 2017-04-29.

- Carlson, Carl E. (May 2015). "The proton radius puzzle". Progress in Particle and Nuclear Physics. 82: 59–77. arXiv:1502.05314. Bibcode:2015PrPNP..82...59C. doi:10.1016/j.ppnp.2015.01.002. S2CID 54915587.

- Burkert, V. D.; Elouadrhiri, L.; Girod, F. X. (16 May 2018). "The pressure distribution inside the proton". Nature. 557 (7705): 396–399. Bibcode:2018Natur.557..396B. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0060-z. OSTI 1438388. PMID 29769668. S2CID 21724781.

- Headrick, J. M.; Diken, E. G.; Walters, R. S.; Hammer, N. I.; Christie, R. A.; Cui, J.; Myshakin, E. M.; Duncan, M. A.; Johnson, M. A.; Jordan, K. D. (2005). "Spectral Signatures of Hydrated Proton Vibrations in Water Clusters". Science. 308 (5729): 1765–1769. Bibcode:2005Sci...308.1765H. doi:10.1126/science.1113094. PMID 15961665. S2CID 40852810.

- "Apollo 11 Mission". Lunar and Planetary Institute. 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-12.

- "Space Travel and Cancer Linked? Stony Brook Researcher Secures NASA Grant to Study Effects of Space Radiation". Brookhaven National Laboratory. 12 December 2007. Archived from the original on 26 November 2008. Retrieved 2009-06-12.

- Shukitt-Hale, B.; Szprengiel, A.; Pluhar, J.; Rabin, B. M.; Joseph, J. A. (2004). "The effects of proton exposure on neurochemistry and behavior". Advances in Space Research. 33 (8): 1334–9. Bibcode:2004AdSpR..33.1334S. doi:10.1016/j.asr.2003.10.038. PMID 15803624. Archived from the original on 2011-07-25. Retrieved 2009-06-12.

- Green, N. W.; Frederickson, A. R. (2006). "A Study of Spacecraft Charging due to Exposure to Interplanetary Protons" (PDF). AIP Conference Proceedings. 813: 694–700. Bibcode:2006AIPC..813..694G. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.541.4495. doi:10.1063/1.2169250. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-05-27. Retrieved 2009-06-12.

- Planel, H. (2004). Space and life: an introduction to space biology and medicine. CRC Press. pp. 135–138. ISBN 978-0-415-31759-7.

- Gabrielse, G. (2006). "Antiproton mass measurements". International Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 251 (2–3): 273–280. Bibcode:2006IJMSp.251..273G. doi:10.1016/j.ijms.2006.02.013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Proton. |

- Particle Data Group at LBL

- Large Hadron Collider

- Eaves, Laurence; Copeland, Ed; Padilla, Antonio (Tony) (2010). "The shrinking proton". Sixty Symbols. Brady Haran for the University of Nottingham.