Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate

The Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate[3][4][5] (Arabic: متصرفية جبل لبنان; Turkish: Cebel-i Lübnan Mutasarrıflığı) was one of the Ottoman Empire's subdivisions following the Tanzimat reform. After 1861 there existed an autonomous Mount Lebanon with a Christian mutasarrıf, which had been created as a homeland for the Maronites under European diplomatic pressure following the 1860 massacres.

| Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate Cebel-i Lübnan Mutasarrıflığı | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mutasarrifate of the Ottoman Empire | |||||||||

| 1861–1918 | |||||||||

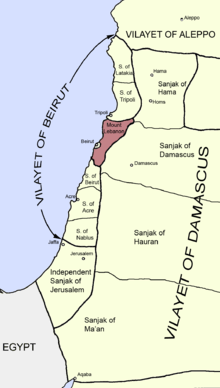

The Mutasarrifate in 1914 | |||||||||

| Capital | Deir el Qamar[1] | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 1870[2] | 110,000 | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Established | 1861 | ||||||||

| 1918 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

Background

1840 Mount Lebanon conflict

As the Ottoman Empire began to decline, the administrative structure came under pressure. Following continued animosity and fighting between the Maronites and the Druze, representatives of the European powers proposed to Sultan Abdülmecid I that the Lebanon be partitioned into Christian and Druze sections. The Sublime Porte was finally compelled to relinquish its plans for the direct rule of the Lebanon, and on December 7, 1842, the sultan adopted prince Metternich's proposal and asked Assad Pasha, the governor (wali) of Beirut, to divide the Mount Lebanon, into two districts: a northern district under a Christian Kaymakam and a southern district under a Druze Kaymakam, both chosen among tribal leaders. Both officials were to report to the governor of Sidon, who resided in Beirut.[6][7]

1860 civil war

On May 22, 1860, a small group of Maronites fired on a group of Druze at the entrance to Beirut , killing one and wounding two. This sparked a torrent of violence which swept through Lebanon. In a mere three days, from May 29 to 31, 60 villages were destroyed in the vicinity of Beirut.[6] 33 Christians and 48 Druze were killed.[8] By June the disturbances had spread to the “mixed” neighbourhoods of southern Lebanon and the Anti Lebanon, to Sidon, Hasbaya, Rashaya, Deir el Qamar, and Zahlé. The Druze peasants laid siege to Catholic monasteries and missions, burnt them, and killed the monks.[6] France intervened on behalf of the local Christian population and Britain on behalf of the Druze after the massacres, in which over 10,000 Christians were killed.[9][10]

History

Creation of the Mutasarrifate

On 5 September 1860, an international commission composed of France, Britain, Austria, Prussia, Russia and the Ottoman Empire met to investigate the causes of the events of 1860 and to recommend a new administrative and judicial system for Lebanon that would prevent the recurrence of such events. In the 1861 "Règlement Organique", Mount Lebanon was preliminarily separated from Syria and reunited under a non-Lebanese Christian mutasarrıf (governor) appointed by the Ottoman sultan, with the approval of the European powers. Mount Lebanon became a semi-autonomous mutasarrifate.[11][12] In September 1864, the statute became permanent.[11][13][14] The mutasarrıf was to be assisted by an administrative council of twelve members from the various religious communities in Lebanon. Each of the six religious groups inhabiting the Lebanon (Maronites, Druzes, Sunni, Shi’a, Greek Orthodox and Melkite) elected two members to the council.[10][11]

This Mutasarrifate system lasted from 1861 until 1918,[15] although it was de facto abolished by Djemal Pasha (one of the "Three Pashas" of the World War I-era Ottoman leadership) in 1915, after which he appointed his own governors.

Naming

The members of the international commission researched many names for the new administrative division and its governor. Many titles were considered; Emir (أمير) was quickly refuted because it was offensive to the Ottoman Porte (Emir being a title of the Ottoman Sultan) and was reminiscent of the Emirate system that the Ottomans fought to abolish. Vali (والي) also fell from consideration because the commission members wanted to convey the importance of the rank of the new title which was above than to that of the Ottoman governors of nearby vilayets; "Governor" (حاكم) was also abandoned because they thought the title was commonplace and widespread. The commission members also ruminated over the title of "President" (رئيس جمهورية) but the designation was not approved by the Ottoman government. After two weeks of deliberation, the French term plénipotentiaire was agreed upon and its Turkish translation mutasarrıf was adopted as the new title for the governor and for the division, which was dubbed in Arabic as the mutasarrifiyah of Mount Lebanon.[16]

List of mutasarrifs

Eight mutasarrifs were appointed and ruled according to the basic mutasarrifate regulation that was issued in 1861 then modified by the 1864 reform. These were:

| Period | Known name | Birth name | Confession / Religion | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1861–1868 | Davud Pasha | Garabet Artin Davoudian | Armenian Catholic | Ottoman Armenian from Istanbul |

| 1868–1873 | Franko Pasha | Nasri Franco Coussa | Greek Catholic (Melkite) | Syrian from Aleppo |

| 1873–1883 | Rüstem Pasha | Rüstem Mariani | Roman Catholic | Italian from Florence, naturalized Ottoman citizen |

| 1883–1892 | Wassa Pasha | Vaso Pashë Shkodrani | Albanian Catholic | Albanian from Shkodër |

| 1892–1902 | Naoum Pasha | Naum Coussa | Greek Catholic (Melkite) | Syrian, stepson of second mutassarrif Nasri Franco Coussa (Franko Pasha) |

| 1902–1907 | Muzaffer Pasha | Ladislas Czaykowski | Roman Catholic | Polish |

| 1907–1912 | Yusuf Pasha | Youssef Coussa | Greek Catholic (Melkite) | Syrian, son of second mutassarrif Nasri Franco Coussa (Franko Pasha) |

| 1912–1915 | Ohannes Pasha | Ohannes Kouyoumdjian | Armenian Catholic | Ottoman Armenian |

The mnemonic word "DaFRuWNaMYO" (in Arabic, دفرونميا) helped school children memorize the name of the mutasarrifs.

List of Governors

When the First World War broke out in 1914, Djemal Pasha occupied Mount Lebanon militarily and revoked the mutasarrifate system. He appointed the mutasarrifs during this period. Those governors were:

- Ali Münif Bey

- Ismail Bey

- Mümtaz Bey[15]

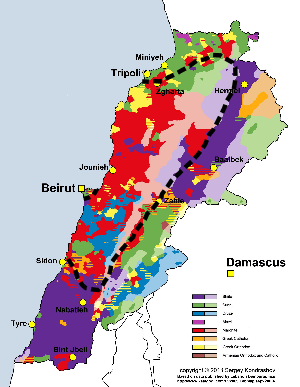

Demographics

The total population in 1895 was estimated as 399,530, with 80,234 (20.1%) Muslims and 319,296 (79.9%) Christians.[17] In 1913, the total population was estimated as 414,747, with 85,232 (20.6%) Muslims and 329,482 (79.4%) Christians.[17]

1895 and 1913 censuses

Source:[17]

| Religion | 1895 | % | 1913 | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sunni | 13,576 | 3.5 | 14,529 | 3.6 |

| Shia | 16,846 | 4.3 | 23,413 | 5.5 |

| Druze | 49,812 | 12.5 | 47,290 | 11.3 |

| Maronite | 229,680 | 57.5 | 242,308 | 58.3 |

| Greek Catholic | 34,472 | 8.5 | 31,936 | 7.7 |

| Greek Orthodox | 54,208 | 13.5 | 52,536 | 12.8 |

| Other Christians

(mainly Protestants) |

936 | 0.3 | 2,882 | 0.7 |

| Total population | 399,530 | 100 | 414,747 | 100 |

Gallery

Davud Pasha, first mutasarrıf from 1861 to 1868

Davud Pasha, first mutasarrıf from 1861 to 1868 Pashko Vasa, aka Wassa Pasha, mutasarrıf from 1883 to 1892

Pashko Vasa, aka Wassa Pasha, mutasarrıf from 1883 to 1892 Ohannes Pasha Kouyoumdjian, mutasarrıf from 1912 to 1915

Ohannes Pasha Kouyoumdjian, mutasarrıf from 1912 to 1915 Lebanese soldiers during the Mutasarrifia period of Mount Lebanon

Lebanese soldiers during the Mutasarrifia period of Mount Lebanon Ali Münif Bey, a governor of Mount Lebanon during World War I

Ali Münif Bey, a governor of Mount Lebanon during World War I

Maps

.jpg) 1862 map

1862 map 1893 map

1893 map 1900 map

1900 map.jpg) 1907 map

1907 map

See also

References

- Pavet de Courteille, Abel (1876). État présent de l'empire ottoman (in French). J. Dumaine. pp. 112–113.

- Reports by Her Majesty's secretaries of embassy and legation on the ... Great Britain. Foreign office. p. 176.

- Fisk, Robert; Debevoise, Malcolm; Kassir, Samir (2010). Beirut. University of California Press. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-520-25668-2.

- Salwa C. Nassar Foundation (1969). Cultural resources in Lebanon. Beirut: Librarie du Liban. p. 74.

- Winslow, Charles (1996). Lebanon: war and politics in a fragmented society. Routledge. p. 291. ISBN 978-0-415-14403-2.

- Lutsky, Vladimir Borisovich (1969). "Modern History of the Arab Countries". Progress Publishers. Retrieved 2009-11-12.

- United States Library of Congress - Federal Research Division (2004). Lebanon A Country Study. Kessinger Publishing. p. 264. ISBN 978-1-4191-2943-8.

- Ceasar E. Farah (2000). Politics of Interventionism in Ottoman Lebanon, 1830-1861. I.B.Tauris. p. 564. ISBN 978-1-86064-056-8. Retrieved 2013-06-30.

- Fawaz, Leila Tarazi (1995). Occasion for War: Civil Conflict in Lebanon and Damascus in 1860 (illustrated ed.). I.B.Tauris & Company. p. 320. ISBN 978-1-86064-028-5.

- U.S. Library of Congress. "Lebanon - Religious Conflicts". countrystudies.us. Retrieved 2009-11-23.

- Lutsky, Vladimir Borisovich. "Modern History of the Arab Countries, sections 11-12".

- The Origins of the Lebanese National Idea, 1840-1920, p. 99. Carol Hakim, University of California Press, 2013. ISBN 9780520273412

- Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire, p. 414. Gabor Agoston, Bruce Masters, Infobase Publishing, 2009. ISBN 9781438110257

- The Arabs of the Ottoman Empire, 1516-1918: A Social and Cultural History, pp. 181-182. Bruce Masters, Cambridge University Press, 2013. ISBN 978-1-107-03363-4

- el-Mallah, Abdallah. "The system of Moutasarrifiat rule". abdallahmallah.com. Archived from the original on 2010-12-31. Retrieved 2009-11-16.

- عهد المتصرفين في لبنان، لحد خاطر: "لماذا سُميت المتصرفيّة"، صفحة: 11-12 (in Arabic)

- Joseph Chamie (1981-04-30). Religion and Fertility: Arab Christian-Muslim Differentials. CUP Archive. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-521-28147-8. Retrieved 2013-06-28.