Old Occitan

Old Occitan (Modern Occitan: occitan ancian, Catalan: occità antic), also called Old Provençal, was the earliest form of the Occitano-Romance languages, as attested in writings dating from the eighth through the fourteenth centuries.[2][3] Old Occitan generally includes Early and Old Occitan. Middle Occitan is sometimes included in Old Occitan, sometimes in Modern Occitan.[4] As the term occitanus appeared around the year 1300,[5] Old Occitan is referred to as "Romance" (Occitan: romans) or "Provençal" (Occitan: proensals) in medieval texts.

| Old Occitan | |

|---|---|

| Old Provençal | |

| Region | Languedoc, Provence, Dauphiné, Auvergne, Limousin, Aquitaine, Gascony |

| Era | 8th–14th centuries |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | pro |

| ISO 639-3 | pro |

| Glottolog | oldp1253[1] |

History

Among the earliest records of Occitan are the Tomida femina, the Boecis and the Cançó de Santa Fe. Old Occitan, the language used by the troubadours, was the first Romance language with a literary corpus and had an enormous influence on the development of lyric poetry in other European languages. The interpunct was a feature of its orthography and survives today in Catalan and Gascon.

Old Catalan and Old Occitan diverged between the 11th and the 14th centuries.[6] Catalan never underwent the shift from /u/ to /y/ or the shift from /o/ to /u/ (except in unstressed syllables in some dialects) and so had diverged phonologically before those changes affected Old Occitan.

Phonology

Old Occitan changed and evolved somewhat during its history, but the basic sound system can be summarised as follows:[7]

Consonants

| Bilabial | Labio- dental |

Dental/ alveolar |

Postalveolar/ palatal |

Velar | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ||

| Plosive | p b | t d | k ɡ | ||

| Fricative | f v | s z | |||

| Affricate | ts dz | tʃ dʒ | |||

| Lateral | l | ʎ | |||

| Trill | r | ||||

| Tap | ɾ |

Notes:

- Written ⟨ch⟩ is believed to have represented the affricate [tʃ], but since the spelling often alternates with ⟨c⟩, it may also have represented [k].

- Word-final ⟨g⟩ may sometimes represent [tʃ], as in gaug "joy" (also spelled gauch).

- Intervocalic ⟨z⟩ could represent either [z] or [dz].

- Written ⟨j⟩ could represent either [dʒ] or [j].

Vowels

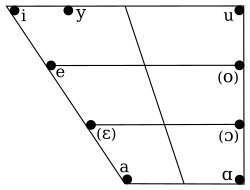

Monophthongs

| Front | Back | |

|---|---|---|

| Close | i y | u |

| Close-mid | e | (o) |

| Open-mid | [ɛ] | [ɔ] |

| Open | a | ɑ |

Notes:

Diphthongs and triphthongs

| IPA | Example | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| falling | ||

| /aj/ | paire | father |

| /aw/ | autre | other |

| /uj/ | conoiser | to know |

| /uw/ | dous | sweet |

| /ɔj/ | pois | then |

| /ɔw/ | mou | it moves |

| /ej/ | vei | I see |

| /ew/ | beure | to drink |

| /ɛj/ | seis | six |

| /ɛw/ | breu | short |

| /yj/ | cuid | I believe |

| /iw/ | estiu | summer |

| rising | ||

| /jɛ/ | miels | better |

| /wɛ/ | cuelh | he receives |

| /wɔ/ | cuolh | he receives |

| triphthongs stress always falls on middle vowel | ||

| /jɛj/ | lieis | her |

| /jɛw/ | ieu | I |

| /wɔj/ | nuoit | night |

| /wɛj/ | pueis | then |

| /wɔw/ | uou | egg |

| /wɛw/ | bueu | ox |

Morphology

Some notable characteristics of Old Occitan:

- It had a two-case system (nominative and oblique), as in Old French, with the oblique derived from the Latin accusative case. The declensional categories were also similar to those of Old French; for example, the Latin third-declension nouns with stress shift between the nominative and accusative were maintained in Old Occitan only in nouns referring to people.

- There were two distinct conditional tenses: a "first conditional", similar to the conditional tense in other Romance language, and a "second conditional", derived from the Latin pluperfect indicative tense. The second conditional is cognate with the literary pluperfect in Portuguese, the -ra imperfect subjunctive in Spanish, the second preterite of very early Old French (Sequence of Saint Eulalia) and probably the future perfect in modern Gascon.

Extracts

- From Bertran de Born's Ab joi mou lo vers e·l comens (c. 1200, translated by James H. Donalson):

Bela Domna·l vostre cors gens |

O pretty lady, all your grace |

See also

Further reading

- Frede Jensen. The Syntax of Medieval Occitan, 2nd edn. De Gruyter, 2015 (1st edn. Tübingen: Niemeyer, 1986). Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für romanische Philologie 208. 978-3-484-52208-4.

- French translation: Frede Jensen. Syntaxe de l'ancien occitan. Tübingen: Niemeyer, 1994.

- William D. Paden. An Introduction to Old Occitan. Modern Language Association of America, 1998. ISBN 0-87352-293-1.

- Romieu, Maurice; Bianchi, André (2002). Iniciacion a l'occitan ancian / Initiation à l'ancien occitan (in Occitan and French). Pessac: Presses Universitaires de Bordeaux. ISBN 2-86781-275-5.

- Povl Skårup. Morphologie élémentaire de l'ancien occitan. Museum Tusculanum Press, 1997, ISBN 87-7289-428-8

- Nathaniel B. Smith & Thomas Goddard Bergin. An Old Provençal Primer. Garland, 1984, ISBN 0-8240-9030-6

References

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Old Provençal". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- Rebecca Posner, The Romance Languages, Cambridge University Press, 1996, ISBN 0-521-28139-3

- Frank M. Chambers, An Introduction to Old Provençal Versification. Diane, 1985 ISBN 0-87169-167-1

- "The Early Occitan period is generally considered to extend from c. 800 to 1000, Old Occitan from 1000 to 1350, and Middle Occitan from 1350 to 1550" in William W. Kibler, Medieval France: An Encyclopedia, Routledge, 1995, ISBN 0-8240-4444-4

- Smith and Bergin, Old Provençal Primer, p. 2

- Riquer, Martí de, Història de la Literatura Catalana, vol. 1. Barcelona: Edicions Ariel, 1964

- The charts are based on phonologies given in Paden, William D., An Introduction to Old Occitan, New York 1998

- See Paden 1998, p. 101