Ogoni people

The Ogoni people (also known as the Ogonis) are people in the region of Southeastern Senatorial district in Rivers State Nigeria. They now number about over two million people and live in a 404-square-mile (1,050 km2) homeland which they also refer to as Ogoni, or Ogoniland. They share common oil-related environmental problems with the Ijaw people of Niger Delta.

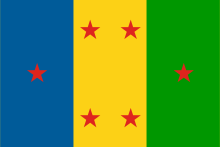

Ogoni flag designed by Nathaniel Wintraub | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 500,000 (1963 census), current population is over two million (Ben Ikari. 2016) and lays claims to the single largest ethnic group in Rivers State Nigeria. | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Nigeria | |

| Languages | |

| Ogoni languages | |

| Religion | |

| Traditional beliefs, Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Ibibio, Igbo, Ikwere, Ijaw, Efik, Ejagham, Annang |

The Ogoni rose to international attention after a massive public protest campaign against Shell Oil, led by the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP), which is also a member of the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization (UNPO).

Geography

The territory is located in Rivers State on the coast of the Gulf of Guinea, east of the city of Port Harcourt. It extends across the Local Government Areas (LGAs) of Khana, Gokana, Eleme and Tai. Traditionally, Ogoniland was divided into the six kingdoms: Babbe, Gokana, Ken-Khana, Nyo-Khana, Eleme and Tai. Nyo-Khana is on the East while Ken-Khana is on the west.

Languages

There are multiple languages spoken by the Ogoni. The largest is Khana, which mutually intelligible with the dialects of the six kingdoms, Gokana, Tae (Tẹẹ), Eleme, and Baen Ogoi[1] part of the linguistic diversity of the Niger Delta.

History

According to oral tradition, the Ogoni people migrated from ancient Ghana down to the Atlantic coast eventually making their way over to the eastern Niger Delta. Linguistic calculations done by Kay Williamson place the Ogoni in the Niger Delta since before 15 BC, making them one of the oldest settlers in the eastern Niger Delta region. Radiocarbon dating taken from sites around Ogoniland and the neighboring communities oral traditions also support this claim.[2] Traditionally, the Ogoni are agricultural, also known for livestock herding, fishing, salt and palm oil cultivation and trade.

Like many peoples on the Guinea coast, the Ogoni have an internal political structure subject to community-by-community arrangement, including appointment of chiefs and community development bodies, some recognized by government and others not. They survived the period of the slave trade in relative isolation, and did not lose any of their members to enslavement. After Nigeria was colonized by the British in 1885, British soldiers arrived in Ogoni by 1901. Major resistance to their presence continued through 1914.

The Ogoni were integrated into a succession of economic systems at a pace that was extremely rapid and exacted a great toll from them. At the turn of the twentieth century, “the world to them did not extend beyond the next three or four villages,” but that soon changed. Ken Saro-Wiwa, the late president of MOSOP, described the transition this way: “if you then think that within the space of seventy years they were struck by the combined forces of modernity, colonialism, the money economy, indigenous colonialism and then the Nigerian Civil War, and that they had to adjust to these forces without adequate preparation or direction, you will appreciate the bafflement of the Ogoni people and the subsequent confusion engendered in the society.”[3]

Human rights violations

The Ogoni people have been victims of human rights violations for many years. In 1956, four years before Nigerian Independence, Royal Dutch/Shell, in collaboration with the British government, found a commercially viable oil field on the Niger Delta and began oil production in 1958. In a 15-year period from 1976 to 1991 there were reportedly 2,976 oil spills of about 2.1 million barrels of oil in Ogoniland, accounting for about 40% of the total oil spills of the Royal Dutch/Shell company worldwide.[4]

In a 2011 assessment of over 200 locations in Ogoniland by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), they found that impacts of the 50 years of oil production in the region extended deeper than previously thought. Because of oil spills, oil flaring, and waste discharge, the alluvial soil of the Niger Delta is no longer viable for agriculture. Furthermore, in many areas that seemed to be unaffected, groundwater was found to have high levels of hydrocarbons or were contaminated with benzene, a carcinogen, at 900 levels above WHO guidelines.[5]

UNEP estimated that it could take up to 30 years to rehabilitate Ogoniland to its full potential and that the first five years of rehabilitation would require funding of about US$1 billion. In 2012, the Nigerian Minister of Petroleum Resources, Deizani Alison-Madueke, announced the establishment of the Hydrocarbon Pollution Restoration Project, which intends to follow the UNEP report suggestions of Ogoniland to prevent further degradation.[6]

In 1990, under the leadership of activist and environmentalist Ken Saro-Wiwa, the Movement of the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP) planned to take action against the Federal Republic of Nigeria and the oil companies. In October 1990, MOSOP presented The Ogoni Bill of Rights to the government. The Bill hoped to gain political and economic autonomy for the Ogoni people, leaving them in control of the natural resources of Ogoniland protecting against further land degradation.[7] The movement lost steam in 1994 after Saro-Wiwa and several other MOSOP leaders were executed by the Nigerian government

In 1993, following protests that were designed to stop contractors from laying a new pipeline for Shell, the Mobile Police raided the area to quell the unrest. In the chaos that followed, it has been alleged that 27 villages were raided, resulting in the death of 2,000 Ogoni people and displacement of 80,000.[8][9][10][11]

Notes

- "Browse by Language Family". Ethnologue. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- Kpone-Tonwe, Sonpie (1997). "Property Reckoning and Methods of Accumulating Wealth among the Ogoni of the Eastern Niger Delta". Africa: Journal of the International African Institute. 1. 67 (1): 130–158. doi:10.2307/1161273. JSTOR 1161273.

- Quotes from Ken Saro-Wiwa, "Letter to Ogoni Youth."

- Crayford, Steven (1 April 1996). "Ogoni Uprising". Africa Today. 2. 42 (Conflict and Conflict Resolution in Africa): 183–197.

- United Nations Environment Programme (August 4, 2011). "UNEP Ogoniland Oil Assessment Reveals Extent of Environmental Contamination and Threats to Human Health". UNEP News Center.

- United Nations Environment Programme (August 1, 2012). "UNEP Welcomes Nigerian Governments Green Light for Ogoniland Oil Clean-Up". UNEP News Center.

- The Movement of the Survival of the Ogoni People. "Ogoni Bill of Rights". Saros International Publishers.

- David Kupfer, "Worldwide Shell boycott", The Progressive, 1996

- PBS documentary, The New Americans: The Ogoni Refugees

- Ken Saro-Wiwa, "Genocide in Nigeria: The Ogoni Tragedy"

- Bogumil Terminski, Oil-Induced Displacement and Resettlement: Social Problem and Human Rights Issue

References

- Brosnahan, L.F. 1967. A word list of the Gokana dialect of Ogoni. Journal of West African Languages, 143-52.

- Hyman, L.M. 1982. The representation of nasality in Gokana. In: The structure of phonological representations. ed. H. van der Hulst & Norval Smith. 111–130. Dordrecht: Foris.

- Hyman, L.M. 1983. Are there syllables in Gokana? In: Current issues in African linguistics, 2. Kaye et al. 171–179. Dordrecht: Foris.

- Ikoro, S.M. 1989. Segmental phonology and lexicon of Proto-Keggoid. University of Port Harcourt: M.A. thesis.

- Ikoro, S.M. 1996. The Kana language. Leiden: CNWS.

- Jeffreys, M.D.W. 1947. Ogoni Pottery. Man, 47: 81–83.

- Piagbo, B.S. 1981. A comparison of the sounds of English and Kana. B.A. project, University of Port Harcourt.

- Thomas, N.W. 1914. Specimens of languages from Southern Nigeria. London: Harrison & Sons.

- Vopnu, S.K. 1991. Phonological Processes and Syllable Structures in Gokana. M.A. Department of Linguistics and Nigerian Languages, University of Port Harcourt.

- Vọbnu, S.K. 2001. Origin and languages of Ogoni people. Boori, KHALGA: Ogoni Languages and Bible Center.

- Williamson, K. 1985. How to become a Kwa language. In Linguistics and Philosophy. Essays in Honor of Ruben S. Wells. eds. A. Makkai and A. Melby. Current Issues in Linguistic Theory, 42. Benjamins, Amsterdam.

- Wolff, H. 1959. Niger Delta languages I: classification. Anthropological Linguistics, 1(8):32–35.

- Wolff, H. 1964. Synopsis of the Ogoni languages. Journal of African languages, 3:38–51.

- Zua, B.A. 1987. The noun phrase in Gokana. B.A. project, University of Port Harcourt.