Bird nest

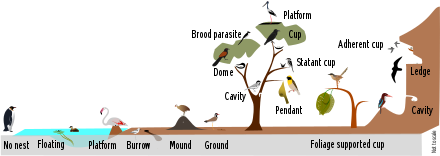

A bird nest is the spot in which a bird lays and incubates its eggs and raises its young. Although the term popularly refers to a specific structure made by the bird itself—such as the grassy cup nest of the American robin or Eurasian blackbird, or the elaborately woven hanging nest of the Montezuma oropendola or the village weaver—that is too restrictive a definition. For some species, a nest is simply a shallow depression made in sand; for others, it is the knot-hole left by a broken branch, a burrow dug into the ground, a chamber drilled into a tree, an enormous rotting pile of vegetation and earth, a shelf made of dried saliva or a mud dome with an entrance tunnel. The smallest bird nests are those of some hummingbirds, tiny cups which can be a mere 2 cm (0.8 in) across and 2–3 cm (0.8–1.2 in) high.[1] At the other extreme, some nest mounds built by the dusky scrubfowl measure more than 11 m (36 ft) in diameter and stand nearly 5 m (16 ft) tall.[2] The study of birds' nests is known as caliology.

Not all bird species build nests. Some species lay their eggs directly on the ground or rocky ledges, while brood parasites lay theirs in the nests of other birds, letting unwitting "foster parents" do the work of rearing the young. Although nests are primarily used for breeding, they may also be reused in the non-breeding season for roosting and some species build special dormitory nests or roost nests (or winter-nest) that are used only for roosting.[3] Most birds build a new nest each year, though some refurbish their old nests.[4] The large eyries (or aeries) of some eagles are platform nests that have been used and refurbished for several years.

In the majority of nest building species the female does most or all of the nest construction, in others both partners contribute; sometimes the male builds the nest and the hen lines it.[5][6] In some polygynous species, however, the male does most or all of the nest building. The nest may also form a part of the courtship display such as in weaver birds. The ability to choose and maintain good nest sites and build high quality nests may be selected for by females in these species. In some species the young from previous broods may also act as helpers for the adults.

Types

Not every bird species builds or uses a nest. Some auks, for instance—including common murre, thick-billed murre and razorbill—lay their eggs directly onto the narrow rocky ledges they use as breeding sites.[7] The eggs of these species are dramatically pointed at one end, so that they roll in a circle when disturbed. This is critical for the survival of the developing eggs, as there are no nests to keep them from rolling off the side of the cliff. Presumably because of the vulnerability of their unprotected eggs, parent birds of these auk species rarely leave them unattended.[8] Nest location and architecture is strongly influenced by local topography and other abiotic factors.[9]

King penguins and emperor penguins also do not build nests; instead, they tuck their eggs and chicks between their feet and folds of skin on their lower bellies. They are thus able to move about while incubating, though in practice only the emperor penguin regularly does so. Emperor penguins breed during the harshest months of the Antarctic winter, and their mobility allows them to form huge huddled masses which help them to withstand the extremely high winds and low temperatures of the season. Without the ability to share body heat (temperatures in the centre of tight groups can be as much as 10C above the ambient air temperature), the penguins would expend far more energy trying to stay warm, and breeding attempts would probably fail.[10]

Some crevice-nesting species, including ashy storm-petrel, pigeon guillemot, Eurasian eagle-owl and Hume's tawny owl, lay their eggs in the relative shelter of a crevice in the rocks or a gap between boulders, but provide no additional nest material.[11][12] Potoos lay their single egg directly atop a broken stump, or into a shallow depression on a branch—typically where an upward-pointing branch died and fell off, leaving a small scar or knot-hole.[13] Brood parasites, such as the New World cowbirds, the honeyguides, and many of the Old World and Australasian cuckoos, lay their eggs in the active nests of other species.[14][15][16]

Scrape

The simplest nest construction is the scrape, which is merely a shallow depression in soil or vegetation.[17] This nest type, which typically has a rim deep enough to keep the eggs from rolling away, is sometimes lined with bits of vegetation, small stones, shell fragments or feathers.[18] These materials may help to camouflage the eggs or may provide some level of insulation; they may also help to keep the eggs in place, and prevent them from sinking into muddy or sandy soil if the nest is accidentally flooded.[19] Ostriches, most tinamous, many ducks, most shorebirds, most terns, some falcons, pheasants, quail, partridges, bustards and sandgrouse are among the species that build scrape nests.

Eggs and young in scrape nests, and the adults that brood them, are more exposed to predators and the elements than those in more sheltered nests; they are on the ground and typically in the open, with little to hide them. The eggs of most ground-nesting birds (including those that use scrape nests) are cryptically coloured to help camouflage them when the adult is not covering them; the actual colour generally corresponds to the substrate on which they are laid.[20] Brooding adults also tend to be well camouflaged, and may be difficult to flush from the nest. Most ground-nesting species have well-developed distraction displays, which are used to draw (or drive) potential predators from the area around the nest.[21] Most species with this type of nest have precocial young, which quickly leave the nest upon hatching.[22]

In cool climates (such as in the high Arctic or at high elevations), the depth of a scrape nest can be critical to both the survival of developing eggs and the fitness of the parent bird incubating them. The scrape must be deep enough that eggs are protected from the convective cooling caused by cold winds, but shallow enough that they and the parent bird are not too exposed to the cooling influences of ground temperatures, particularly where the permafrost layer rises to mere centimeters below the nest. Studies have shown that an egg within a scrape nest loses heat 9% more slowly than an egg placed on the ground beside the nest; in such a nest lined with natural vegetation, heat loss is reduced by an additional 25%.[23] The insulating factor of nest lining is apparently so critical to egg survival that some species, including Kentish plovers, will restore experimentally altered levels of insulation to their pre-adjustment levels (adding or subtracting material as necessary) within 24 hours.[24]

In warm climates, such as deserts and salt flats, heat rather than cold can kill the developing embryos. In such places, scrapes are shallower and tend to be lined with non-vegetative material (including shells, feathers, sticks and soil),[25] which allows convective cooling to occur as air moves over the eggs. Some species, such as the lesser nighthawk and the red-tailed tropicbird, help reduce the nest's temperature by placing it in partial or full shade.[26][27] Others, including some shorebirds, cast shade with their bodies as they stand over their eggs. Some shorebirds also soak their breast feathers with water and then sit on the eggs, providing moisture to enable evaporative cooling.[28] Parent birds keep from overheating themselves by gular panting while they are incubating, frequently exchanging incubation duties, and standing in water when they are not incubating.[29]

The technique used to construct a scrape nest varies slightly depending on the species. Beach-nesting terns, for instance, fashion their nests by rocking their bodies on the sand in the place they have chosen to site their nest,[30] while skimmers build their scrapes with their feet, kicking sand backwards while resting on their bellies and turning slowly in circles.[31] The ostrich also scratches out its scrape with its feet, though it stands while doing so.[32] Many tinamous lay their eggs on a shallow mat of dead leaves they have collected and placed under bushes or between the root buttresses of trees,[33] and kagus lay theirs on a pile of dead leaves against a log, tree trunk or vegetation.[34] Marbled godwits stomp a grassy area flat with their feet, then lay their eggs, while other grass-nesting waders bend vegetation over their nests so as to avoid detection from above.[35] Many female ducks, particularly in the northern latitudes, line their shallow scrape nests with down feathers plucked from their own breasts, as well as with small amounts of vegetation.[36] Among scrape-nesting birds, the three-banded courser and Egyptian plover are unique in their habit of partially burying their eggs in the sand of their scrapes.[37]

Mound

Burying eggs as a form of incubation reaches its zenith with the Australasian megapodes. Several megapode species construct enormous mound nests made of soil, branches, sticks, twigs and leaves, and lay their eggs within the rotting mass. The heat generated by these mounds, which are in effect giant compost heaps, warms and incubates the eggs.[1] The nest heat results from the respiration of thermophilic fungi and other microorganisms.[38] The size of some of these mounds can be truly staggering; several of the largest—which contain more than 100 cubic metres (130 cu yd) of material, and probably weigh more than 50 tons (45,000 kg)[38]—were initially thought to be Aboriginal middens.[39]

In most mound-building species, males do most or all of the nest construction and maintenance. Using his strong legs and feet, the male scrapes together material from the area around his chosen nest site, gradually building a conical or bell-shaped pile. This process can take five to seven hours a day for more than a month. While mounds are typically reused for multiple breeding seasons, new material must be added each year in order to generate the appropriate amount of heat. A female will begin to lay eggs in the nest only when the mound's temperature has reached an optimal level.[40]

Both the temperature and the moisture content of the mound are critical to the survival and development of the eggs, so both are carefully regulated for the entire length of the breeding season (which may last for as long as eight months), principally by the male.[38] Ornithologists believe that megapodes may use sensitive areas in their mouths to assess mound temperatures; each day during the breeding season, the male digs a pit into his mound and sticks his head in.[41] If the mound's core temperature is a bit low, he adds fresh moist material to the mound, and stirs it in; if it is too high, he opens the top of the mound to allow some of the excess heat to escape. This regular monitoring also keeps the mound's material from becoming compacted, which would inhibit oxygen diffusion to the eggs and make it more difficult for the chicks to emerge after hatching.[40] The malleefowl, which lives in more open forest than do other megapodes, uses the sun to help warm its nest as well—opening the mound at midday during the cool spring and autumn months to expose the plentiful sand incorporated into the nest to the sun's warming rays, then using that warm sand to insulate the eggs during the cold nights. During hot summer months, the malleefowl opens its nest mound only in the cool early morning hours, allowing excess heat to escape before recovering the mound completely.[42] One recent study showed that the sex ratio of Australian brushturkey hatchlings correlated strongly with mound temperatures; females hatched from eggs incubated at higher mean temperatures.[43]

Flamingos make a different type of mound nest. Using their beaks to pull material towards them,[44] they fashion a cone-shaped pile of mud between 15–46 cm (6–18 in) tall, with a small depression in the top to house their single egg.[45] The height of the nest varies with the substrate upon which it is built; those on clay sites are taller on average than those on dry or sandy sites.[44] The height of the nest and the circular, often water-filled trench which surrounds it (the result of the removal of material for the nest) help to protect the egg from fluctuating water levels and excessive heat at ground level. In East Africa, for example, temperatures at the top of the nest mound average some 20 °C (40 °F) cooler than those of the surrounding ground.[44]

The base of the horned coot's enormous nest is a mound built of stones, gathered one at a time by the pair, using their beaks. These stones, which may weigh as much as 450 g (about a pound) each, are dropped into the shallow water of a lake, making a cone-shaped pile which can measure as much as 4 m2 (43 sq ft) at the bottom and 1 m2 (11 sq ft) at the top, and 0.6 m (2.0 ft) in height. The total combined weight of the mound's stones may approach 1.5 tons (1,400 kg). Once the mound has been completed, a sizable platform of aquatic vegetation is constructed on top. The entire structure is typically reused for many years.[46]

Burrow

Soil plays a different role in the burrow nest; here, the eggs and young—and in most cases the incubating parent bird—are sheltered under the earth. Most burrow-nesting birds excavate their own burrows, but some use those excavated by other species and are known as secondary nesters; burrowing owls, for example, sometimes use the burrows of prairie dogs, ground squirrels, badgers or tortoises,[47] China's endemic white-browed tits use the holes of ground-nesting rodents[48] and common kingfishers occasionally nest in rabbit burrows.[49] Burrow nests are particularly common among seabirds at high latitudes, as they provide protection against both cold temperatures and predators.[50] Puffins, shearwaters, some megapodes, motmots, todies, most kingfishers, the crab plover, miners and leaftossers are among the species which use burrow nests.

Most burrow nesting species dig a horizontal tunnel into a vertical (or nearly vertical) dirt cliff, with a chamber at the tunnel's end to house the eggs.[51] The length of the tunnel varies depending on the substrate and the species; sand martins make relatively short tunnels ranging from 50–90 cm (20–35 in),[52] for example, while those of the burrowing parakeet can extend for more than three meters (nearly 10 ft).[53] Some species, including the ground-nesting puffbirds, prefer flat or gently sloping land, digging their entrance tunnels into the ground at an angle.[54] In a more extreme example, the D'Arnaud's barbet digs a vertical tunnel shaft more than a meter (39 in) deep, with its nest chamber excavated off to the side at some height above the shaft's bottom; this arrangement helps to keep the nest from being flooded during heavy rain.[55] Buff-breasted paradise-kingfishers dig their nests into the compacted mud of active termite mounds, either on the ground or in trees.[49] Specific soil types may favour certain species and it is speculated that several species of bee-eater favor loess soils which are easy to penetrate.[56][57]

Birds use a combination of their beaks and feet to excavate burrow nests. The tunnel is started with the beak; the bird either probes at the ground to create a depression, or flies toward its chosen nest site on a cliff wall and hits it with its bill. The latter method is not without its dangers; there are reports of kingfishers being fatally injured in such attempts.[49] Some birds remove tunnel material with their bills, while others use their bodies or shovel the dirt out with one or both feet. Female paradise-kingfishers are known to use their long tails to clear the loose soil.[49]

Some crepuscular petrels and prions are able to identify their own burrows within dense colonies by smell.[58] Sand martins learn the location of their nest within a colony, and will accept any chick put into that nest until right before the young fledge.[59]

Not all burrow-nesting species incubate their young directly. Some megapode species bury their eggs in sandy pits dug where sunlight, subterranean volcanic activity, or decaying tree roots will warm the eggs.[1][38] The crab plover also uses a burrow nest, the warmth of which allows it to leave the eggs unattended for as long as 58 hours.[60]

Predation levels on some burrow-nesting species can be quite high; on Alaska's Wooded Islands, for example, river otters munched their way through some 23 percent of the island's fork-tailed storm-petrel population during a single breeding season in 1977.[61] There is some evidence that increased vulnerability may lead some burrow-nesting species to form colonies, or to nest closer to rival pairs in areas of high predation than they might otherwise do.[62]

Cavity

The cavity nest is a chamber, typically in living or dead wood, but sometimes in the trunks of tree ferns[63] or large cacti, including saguaro.[63][64] In tropical areas, cavities are sometimes excavated in arboreal insect nests.[65][66] A relatively small number of species, including woodpeckers, trogons, some nuthatches and many barbets, can excavate their own cavities. Far more species—including parrots, tits, bluebirds, most hornbills, some kingfishers, some owls, some ducks and some flycatchers—use natural cavities, or those abandoned by species able to excavate them; they also sometimes usurp cavity nests from their excavating owners. Those species that excavate their own cavities are known as "primary cavity nesters", while those that use natural cavities or those excavated by other species are called "secondary cavity nesters". Both primary and secondary cavity nesters can be enticed to use nest boxes (also known as bird houses); these mimic natural cavities, and can be critical to the survival of species in areas where natural cavities are lacking.[67]

Woodpeckers use their chisel-like bills to excavate their cavity nests, a process which takes, on average, about two weeks.[64] Cavities are normally excavated on the downward-facing side of a branch, presumably to make it more difficult for predators to access the nest, and to reduce the chance that rain floods the nest.[68] There is also some evidence that fungal rot may make the wood on the underside of leaning trunks and branches easier to excavate.[68] Most woodpeckers use a cavity for only a single year. The endangered red-cockaded woodpecker is an exception; it takes far longer—up to two years—to excavate its nest cavity, and may reuse it for more than two decades.[64] The typical woodpecker nest has a short horizontal tunnel which leads to a vertical chamber within the trunk. The size and shape of the chamber depends on species, and the entrance hole is typically only as large as is needed to allow access for the adult birds. While wood chips are removed during the excavation process, most species line the floor of the cavity with a fresh bed of them before laying their eggs.

Trogons excavate their nests by chewing cavities into very soft dead wood; some species make completely enclosed chambers (accessed by upward-slanting entrance tunnels), while others—like the extravagantly plumed resplendent quetzal—construct more open niches.[66] In most trogon species, both sexes help with nest construction. The process may take several months, and a single pair may start several excavations before finding a tree or stump with wood of the right consistency.

Species which use natural cavities or old woodpecker nests sometimes line the cavity with soft material such as grass, moss, lichen, feathers or fur. Though a number of studies have attempted to determine whether secondary cavity nesters preferentially choose cavities with entrance holes facing certain directions, the results remain inconclusive.[69] While some species appear to preferentially choose holes with certain orientations, studies (to date) have not shown consistent differences in fledging rates between nests oriented in different directions.[69]

Cavity-dwelling species have to contend with the danger of predators accessing their nest, catching them and their young inside and unable to get out.[70] They have a variety of methods for decreasing the likelihood of this happening. Red-cockaded woodpeckers peel bark around the entrance, and drill wells above and below the hole; since they nest in live trees, the resulting flow of resin forms a barrier that prevents snakes from reaching the nests.[71] Red-breasted nuthatches smear sap around the entrance holes to their nests, while white-breasted nuthatches rub foul-smelling insects around theirs.[72] Eurasian nuthatches wall up part of their entrance holes with mud, decreasing the size and sometimes extending the tunnel part of the chamber. Most female hornbills seal themselves into their cavity nests, using a combination of mud (in some species brought by their mates), food remains and their own droppings to reduce the entrance hole to a narrow slit.[73]

A few birds are known to use the nests of insects within which they create a cavity in which they lay their eggs. These include the rufous woodpecker which nests in the arboreal nests of Crematogaster ants and the collared kingfisher which uses termite nests.[74]

Cup

The cup nest is smoothly hemispherical inside, with a deep depression to house the eggs. Most are made of pliable materials—including grasses—though a small number are made of mud or saliva.[75] Many passerines and a few non-passerines, including some hummingbirds and some swifts, build this type of nest.

Small bird species in more than 20 passerine families, and a few non-passerines—including most hummingbirds, kinglets and crests in the genus Regulus, some tyrant flycatchers and several New World warblers—use considerable amounts of spider silk in the construction of their nests.[76][77] The lightweight material is strong and extremely flexible, allowing the nest to mold to the adult during incubation (reducing heat loss), then to stretch to accommodate the growing nestlings; as it is sticky, it also helps to bind the nest to the branch or leaf to which it is attached.[77]

Many swifts and some hummingbirds[78] use thick, quick-drying saliva to anchor their nests. The chimney swift starts by dabbing two globs of saliva onto the wall of a chimney or tree trunk. In flight, it breaks a small twig from a tree and presses it into the saliva, angling the twig downwards so that the central part of the nest is the lowest. It continues adding globs of saliva and twigs until it has made a crescent-shaped cup.[79]

Cup-shaped nest insulation has been found to be related to nest mass,[80][81] nest wall thickness,[81][82][83] nest depth,[80][81] nest weave density/porosity,[80][82][84] surface area,[81] height above ground [80] and elevation above sea level.[84]

More recently, nest insulation has been found to be related to the mass of the incubating parent.[81] This is known as an allometric relationship. Nest walls are constructed with an adequate quantity of nesting material so that the nest will be capable of supporting the contents of the nest. Nest thickness, nest mass and nest dimensions therefore correlate with the mass of the adult bird.[81] The flow-on consequence of this is that nest insulation is also related to parent mass.[81]

Saucer or plate

The saucer or plate nest, though superficially similar to a cup nest, has at most only a shallow depression to house the eggs.

Platform

The platform nest is a large structure, often many times the size of the (typically large) bird which has built it. Depending on the species, these nests can be on the ground or elevated.[85] In the case of raptor nests, or eyries (also spelt aerie), these are often used for many years, with new material added each breeding season. In some cases, the nests grow large enough to cause structural damage to the tree itself, particularly during bad storms where the weight of the nest can cause additional stress on wind-tossed branches.

Pendant

The pendant nest is an elongated sac woven of pliable materials such as grasses and plant fibers and suspended from a branch. Oropendolas, caciques, orioles, weavers and sunbirds are among the species that weave pendant nests.

Sphere

The sphere nest is a roundish structure; it is completely enclosed, except for a small opening which allows access.

Nest protection and sanitation

Many species of bird conceal their nests to protect them from predators. Some species may choose nest sites that are inaccessible or build the nest so as to deter predators.[86] Bird nests can also act as habitats for other inquiline species which may not affect the bird directly. Birds have also evolved nest sanitation measures to reduce the effects of parasites and pathogens on nestlings.

Some aquatic species such as grebes are very careful when approaching and leaving the nest so as not to reveal the location. Some species will use leaves to cover up the nest prior to leaving.

Ground birds such as plovers may use broken wing or rodent run displays to distract predators from nests.[87]

Many species attack predators or apparent predators near their nests. Kingbirds attack other birds that come too close. In North America, northern mockingbirds, blue jays, and Arctic terns can peck hard enough to draw blood.[88] In Australia, a bird attacking a person near its nest is said to swoop the person. The Australian magpie is particularly well known for this behavior.[89]

Nests can become home to many other organisms including parasites and pathogens.[90] The excreta of the fledglings also pose a problem. In most passerines, the adults actively dispose the fecal sacs of young at a distance or consume them. This is believed to help prevent ground predators from detecting nests.[91] Young birds of prey however usually void their excreta beyond the rims of their nests.[92] Blowflies of the genus Protocalliphora have specialized to become obligate nest parasites with the maggots feeding on the blood of nestlings.[93]

Some birds have been shown to choose aromatic green plant material for constructing nests that may have insecticidal properties,[94][95] while others may use materials such as carnivore scat to repel smaller predators.[96] Some urban birds, house sparrows and house finches in Mexico, have been adopted the use of cellulose from cigarette butts which may be adaptive since these fibres contain nicotine and other toxic substances that repel ectoparasites.[97]

Some birds use pieces of snake slough in their nests.[98] It has been suggested that these may deter some nest predators such as squirrels.[99]

Colonial nesting

Though most birds nest individually, some species—including seabirds, penguins, flamingos, many herons, gulls, terns, weaver, some corvids and some sparrows—gather together in sizeable colonies. Birds that nest colonially may benefit from increased protection against predation. They may also be able to better utilize food supplies, by following more successful foragers to their foraging sites.[100]

In human culture

Many birds may nest close to human habitations. In addition to nest boxes which are often used to encourage cavity nesting birds (see below), other species have been specially encouraged : for example nesting white storks have been protected and held in reverence in many cultures,[101] and the nesting of peregrine falcons on tall modern or historical buildings has captured popular interest.[102]

Colonial breeders produce guano in and around their nesting sites, which is a valuable fertilizer from the Andean Pacific coast and other areas.

The saliva nest of the edible-nest swiftlet is used to make bird's nest soup,[103] long considered a delicacy in China.[104] Collection of the swiftlet nests is big business: in one year, more than 3.5 million nests were exported from Borneo to China,[105] and the industry was estimated at $1 billion US per year (and increasing) in 2008.[103] While the collection is regulated in some areas (at the Gomantong Caves, for example, where nests can be collected only from February to April or July to September), it is not in others, and the swiftlets are declining in areas where the harvest reaches unsustainable levels.[103]

Some species of birds are considered nuisances when they nest in the proximity of human habitations. Feral pigeons are often unwelcome and sometimes also considered as a health risk.[106]

The Beijing National Stadium, principal venue of the 2008 Summer Olympics, has been nicknamed "The Bird Nest" because of its architectural design, which its designers likened to a bird's woven nest.[107]

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, naturalists often collected bird's eggs and their nests. The practice of egg-collecting or oology is now illegal in many jurisdictions worldwide; the study of bird nests is called caliology.[108]

Artificial bird nests

Bird nests are also built by humans to help in the conservation of certain birds (such as swallows). Swallow nests are generally built with plaster, wood, terracotta or stucco.[109][110]

Artificial nests, such as nest boxes, are an important conservation tool for many species, however nest box programs rarely compare their effectiveness with individuals not using nest boxes. Red-footed falcons using nest boxes in heavily managed landscapes produced fewer fledglings than those nesting in natural nests, but also than pairs nesting in nest boxes in more natural habitats.[111]

References

Notes

- Campbell & Lack 1985, p. 386

- Campbell & Lack 1985, p. 345

- Skutch, Alexander F (1960), "The nest as a dormitory", Ibis, 103 (1): 50–70, doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1961.tb02420.x.

- smithsonianscience.org 2015-04-20 Bird nests: Variety is Key for the world’s avian Architects Archived 2017-01-03 at the Wayback Machine

- Campbell & Lack 1985, p. 387

- Felix, Jiri (1973). Garden and Field Birds. Octopus books. p. 17. ISBN 0 7064 0236 7.

- Ehrlich et al. 1994, pp. 228–232

- del Hoyo 1992, p. 692

- Hogan 2010.

- del Hoyo 1992, p. 148

- Ehrlich et al. 1994, p. 252

- Ehrlich et al. 1994, p. 260

- Cohn-Haft 1999, p. 295

- Jaramillo 2001, p. 548

- Short & Horne 2002b, p. 282

- JE, Simon; Pacheco (2005), "On the standardization of nest descriptions of neotropical birds" (PDF), Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia, 13 (2): 143–154, archived (PDF) from the original on 2008-07-20

- Campbell & Lack 1985, p. 390

- Ehrlich et al. 1994, p. xxii

- Ehrlich et al. 1994, p. 441

- Campbell & Lack 1985, p. 174

- Campbell & Lack 1985, p. 145

- Williams, Ernest Herbert (2005), The Nature Handbook: A Guide to Observing the Great Outdoors, Oxford University Press, US, p. 115, ISBN 978-0-19-517194-5

- Reid, J. M.; Cresswell, W.; Holt, S.; Mellanby, R. J.; Whitby, D. P.; Ruxton, G. D (2002), "Nest scrape design and clutch heat loss in the Pectoral Sandpiper (Calidris melanotos)", Functional Ecology, 16 (3): 305–316, doi:10.1046/j.1365-2435.2002.00632.x.

- Szentirmai, István; Székely, Tamás (2002), "Do Kentish plovers regulate the amount of their nest material? An Experimental Test", Behaviour, 139 (6): 847–859, doi:10.1163/156853902320262844, JSTOR 4535956.

- Grant 1982, p. 11.

- Grant 1982, p. 60.

- Howell, Thomas R.; Bartholomew, George A (1962), "Temperature Regulation in the Red-tailed Tropicbird and the Red-footed Booby", The Condor, 64 (1): 6–18, doi:10.2307/1365438, JSTOR 1365438.

- Grant 1982, p. 61.

- Grant 1982, p. 62.

- del Hoyo, Elliott & Sargatal 1996, p. 637

- del Hoyo, Elliott & Sargatal 1996, p. 673

- del Hoyo 1992, p. 80

- del Hoyo 1992, p. 119

- del Hoyo, Elliott & Sargatal 1996, p. 222

- del Hoyo, Elliott & Sargatal 1996, p. 473

- del Hoyo 1992, p. 558

- del Hoyo, Elliott & Sargatal 1996, p. 371

- Elliott 1994, p. 287

- Hansell 2000, p. 9.

- Elliott 1994, p. 288

- Elliott 1994, p. 280

- Elliott 1994, p. 289

- Göth, Anne (2007), "Incubation temperatures and sex ratios in Australian brush-turkey (Alectura lathami) mounds", Austral Ecology, 32 (4): 278–285, doi:10.1111/j.1442-9993.2007.01709.x

- del Hoyo 1992, p. 516

- Seng 2001, p. 188

- Taylor, Barry; van Perlo, Ber (1998), Rails, Sussex: Pica Press, p. 557, ISBN 978-1-873403-59-4

- Behrstock 2001, p. 344

- Harrap & Quinn 1996, p. 21

- Woodall 2001, p. 169

- Davenport, John (1992), Animal Life at Low Temperature, Springer, pp. 81–82, ISBN 978-0-412-40350-7

- Ehrlich et al. 1994, p. xxiii

- Ehrlich et al. 1994, p. 345

- Juniper & Parr 2003, p. 24

- Rasmussen & Collar 2002, p. 119

- Short & Horne 2002a, p. 162

- Smalley, Ian; O'Hara-Dhand, Ken; McLaren, Sue; Svircev, Zorica; Nugent, Hugh (2013). "Loess and bee-eaters I: Ground properties affecting the nesting of European bee-eaters (Merops apiaster L.1758) in loess deposits". Quaternary International. 296: 220–226. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2012.09.005. hdl:2381/31362.

- Heneberg, P. (2009). "Soil penetrability as a key factor affecting nesting of burrowing birds". Ecological Research. 24 (2): 453–459. doi:10.1007/s11284-008-0520-2.

- Bonadonna, Francesco; Cunningham, Gregory B.; Jouventin, Pierre; Hesters, Florence; Nevitt, Gabrielle A. (2003), "Evidence for nest-odour recognition in two species of diving petrel", The Journal of Experimental Biology, 206 (Pt 20): 3719–3722, doi:10.1242/jeb.00610, PMID 12966063.

- Goodenough, Judith; McGuire, Betty; Wallace, Robert A.; Jacob, Elizabeth (2009-09-22), Perspectives on Animal Behavior, Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, p. 430, ISBN 978-0-470-04517-6

- De Marchi, G.; Chiozzi, G.; Fasola, M. (2008), "Solar incubation cuts down parental care in a burrow nesting tropical shorebird, the crab plover Dromas ardeola", Journal of Avian Biology, 39 (5): 484–486, doi:10.1111/j.0908-8857.2008.04523.x

- Boersma, P. Dee; Wheelwright, Nathaniel T.; Nerini, Mary K.; Wheelwright, Eugenia Stevens (April 1980), "The Breeding Biology of the Fork-tailed Storm-Petrel (Oceandroma furcata)" (PDF), Auk, 97 (2): 268–282, archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-08-21

- Ehrlich et al. 1994, p. 17

- Collar 2001, p. 94

- Reed 2001, pp. 380–1

- Brightsmith, Donald J. (2000), "Use of Arboreal Termitaria by Nesting Peruvian Amazon" (PDF), Condor, 102 (3): 529–538, doi:10.1650/0010-5422(2000)102[0529:UOATBN]2.0.CO;2, archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-01-28

- Collar 2001, p. 96

- Phillips, Tina (Winter 2005), "Nest Boxes: More than Just Birdhouses", BirdScope, 19 (1), archived from the original on 2007-07-19

- Conner 1975, p. 373

- Rendell, Wallace B.; Robertson, Raleigh J. (1994), "Cavity Entry Orientation and Nest-site Use by Secondary Hole-nesting Birds" (PDF), Journal of Field Ornithology, 65 (1): 27–35, archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-04

- Perrins, Christopher M; Attenborough, David; Arlott, Norman (1987), New Generation Guide to the Birds of Britain and Europe, Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, p. 230, ISBN 978-0-292-75532-1

- Rudolph, Kyle & Conner 1990

- Reed 2001, p. 437

- Kemp 2001, p. 469

- Moreau, R. E. (1936). "XXVI.-Bird-Insect Nesting Associations". Ibis. 78 (3): 460–471. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1936.tb03399.x.

- Hansell 2000, p. 280.

- Ehrlich et al. 1994, p. 445

- Erickson, Laura (Spring 2008), "The Wonders of Spider Silk", BirdScope, 22 (2): 7

- Gould & Gould 2007, p. 200.

- Gould & Gould 2007, p. 196.

- Kern, M (1984), "Racial differences in nests of white-crowned sparrows", Condor, 86 (4): 455–466, doi:10.2307/1366826, JSTOR 1366826

- Heenan, Caragh; Seymour, R. (2011), "Structural support, not insulation, is the primary driver for avian cup-shaped nest design", Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 278 (1720): 2924–2929, doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.2798, PMC 3151712, PMID 21325330

- Skowron, C; Kern, M. (1980), "The insulation in nests of selected North-American songbirds", Auk, 97: 816–824

- Whittow, F.N.; Berger, A.J. (1977), "Heat loss from the nest of the Hawaiian honeycreeper, 'Amakihi'", Wilson Bulletin, 89: 480–483

- Kern, M. D.; Van Riper, C. (1984), "Altitudinal variations in nests of the Hawaiian honeycreeper Hemignathus virens virens", Condor, 86 (4): 443–454, doi:10.2307/1366825, JSTOR 1366825

- Hyde, Kenneth (2004), Zoology: An Inside View of Animals, Dubuque, IA: Kendall Hunt, p. 474, ISBN 978-0-7575-0997-1

- Rudolph, Kyle & Conner 1990.

- Byrktedal 1989

- Gill 1995

- Kaplan 2004

- Hicks, Ellis A. (1959), Checklist and bibliography on the occurrence of insects in birds' nests, Iowa State College Press, Ames

- Petit, Petit & Petit 1989

- Rosenfeld, Rosenfeld & Gratson 1982

- Sabrosky, Bennett & Whitworth 1989

- Wimberger 1984

- Clark & Mason 1985

- Schuetz 2005

- Suarez-Rodriguez, M.; Lopez-Rull, I.; MacIas Garcia, C. (2012). "Incorporation of cigarette butts into nests reduces nest ectoparasite load in urban birds: New ingredients for an old recipe?". Biology Letters. 9 (1): 20120931. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2012.0931. PMC 3565511. PMID 23221874.

- Strecker, John K (1926), "On the use, by birds, of snakes' sloughs as nesting material" (PDF), Auk, 53 (4): 501–507, doi:10.2307/4075138, JSTOR 4075138, archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-12-24

- Medlin, Elizabeth C.; Risch, Thomas S. (2006), "An experimental test of snake skin use to deter nest predation", The Condor, 108 (4): 963–965, doi:10.1650/0010-5422(2006)108[963:AETOSS]2.0.CO;2

- Ward & Zahavi 1973

- Kushlan, James A. (1997), "The Conservation of Wading Birds", Colonial Waterbirds, 20 (1): 129–137, doi:10.2307/1521775, JSTOR 1521775.

- Cade & Bird 1990

- Couzens, Dominic (2008), Top 100 Birding Sites of the World, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, pp. 85–86, ISBN 978-0-520-25932-4

- Deutsch, Jonathan; Murakhver, Natalya (2012), They Eat That?: A Cultural Encyclopedia of Weird and Exotic Food from Around the World, Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, p. 17, ISBN 978-0-313-38058-7, archived from the original on 2013-06-04

- Khanna, D. R.; Yadav, P. R. (2005), Biology of Birds, New Dehli, India: Discovery Publishing House, p. 129, ISBN 978-81-7141-933-3, archived from the original on 2013-06-03

- Haag-Wackernagel & Moch 2004

- "Competition entries for design of Beijing National Stadium". Beijing Municipal Commission of Urban Planning. Archived from the original on 2008-02-20. Retrieved 2008-02-25.

- Dixon, Charles (1902), Birds' nests, New York: Frederick A Stokes, p. v

- Artificial swallow nests Archived 2014-03-17 at the Wayback Machine

- Terracotta nests Archived 2014-03-17 at the Wayback Machine

- Bragin, E. A.; Bragin, A. E.; Katzner, T. E. (2017). "Demographic consequences of nestbox use for Red-footed Falcons Falco vespertinus in Central Asia". Ibis. 159 (4): 841–853. doi:10.1111/ibi.12503.

Cited texts

- Behrstock, Robert A. (2001), "Typical Owls", in Elphick, Chris; Dunning, Jr., John B.; Sibley, David (eds.), The Sibley Guide to Bird Life & Behaviour, London: Christopher Helm, ISBN 978-0-7136-6250-4

- Byrktedal, Ingvar (1989), "Nest defense behavior of Lesser Golden-Plovers" (PDF), Wilson Bull., 101 (4): 579–590

- Cade, T.J.; Bird, D.M. (1990), "Peregrine Falcons (Falco peregrinus) nesting in an urban environment: a review", Can. Field-Nat., 104: 209–218

- Campbell, Bruce; Lack, Elizabeth, eds. (1985), A Dictionary of Birds, Carlton, England: T and A D Poyser, ISBN 978-0-85661-039-4

- Clark, L.; Mason, J. Russell (1985), "Use of nest material as insecticidal and anti-pathogenic agents by the European Starling", Oecologia, 67 (2): 169–176, doi:10.1007/BF00384280, PMID 28311305

- Cohn-Haft, Mario (1999), "Family Nyctibiidae (Potoos)", in del Hoyo, Josep; Elliott, Andrew; Sargatal, Jordi (eds.), Handbook of Birds of the World, Volume 5: Barn-owls to Hummingbirds, Barcelona: Lynx Edicions, ISBN 978-84-87334-25-2

- Collar, N. J. (2001), "Family Trogonidae (Trogons)", in del Hoyo, Josep; Elliott, Andrew; Sargatal, Jordi (eds.), Handbook of Birds of the World, Volume 6: Mousebirds to Hornbills, Barcelona: Lynx Edicions, ISBN 978-84-87334-30-6

- Collias, Nicholas E. (1997), "On the origin and evolution of nest building by passerine birds" (PDF), Condor, 99 (2): 253–270, doi:10.2307/1369932, JSTOR 1369932

- Conner, Richard N. (1975), "Orientation of entrances to woodpecker nest cavities", Auk, 92 (2): 371–374, doi:10.2307/4084566, JSTOR 4084566

- del Hoyo, Josep (1992), "Family Phoenicopteridae (Flamingos)", in del Hoyo, Josep; Elliott, Andrew; Sargatal, Jordi (eds.), Handbook of Birds of the World, Volume 1: Ostrich to Ducks, Barcelona: Lynx Edicions, ISBN 978-84-87334-10-8

- del Hoyo, Josep; Elliott, Andrew; Sargatal, Jordi, eds. (1996), Handbook of Birds of the World, vol. 3, Barcelona: Lynx Edicions, ISBN 978-84-87334-20-7

- Ehrlich, Paul R.; Dobkin, David S.; Wheye, Darryl; Pimm, Stuart L. (1994), The Birdwatcher's Handbook, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-858407-0

- Elliott, Andrew (1994), "Family Megapodiidae (Megapodes)", in del Hoyo, Josep; Elliott, Andrew; Sargatal, Jordi (eds.), Handbook of Birds of the World, Volume 2: New World Vultures to Guineafowl, Barcelona: Lynx Edicions, ISBN 978-84-87334-15-3

- Gould, James L; Gould, Carol Grant (2007), Animal Architects: Building and the Evolution of Intelligence, New York, NY: Basic Books, ISBN 978-0-465-02782-8

- Grant, Gilbert (1982), Avian Incubation in a Hot Environment, Ornithological Monographs, 30, Washington, DC: American Ornithologists' Union, ISBN 978-0-943610-30-6

- Haag-Wackernagel, D; Moch, H. (2004), "Health hazards posed by feral pigeons", J. Infect., 48 (4): 307–313, doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2003.11.001, PMID 15066331

- Gill, Frank B. (1995), Ornithology, Macmillan, p. 383, ISBN 978-0-7167-2415-5, retrieved 2009-12-16

- Hansell, Mike (2000), Bird Nests and Construction Behaviour, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-01764-0

- Harrap, Simon; Quinn, David (1996), Tits, Nuthatches & Treecreepers, London: Christopher Helm, ISBN 978-0-7136-3964-3

- Hogan, C. Michael (2010), "Abiotic factor", in Emily Monosson; C. Cleveland (eds.), Encyclopedia of Earth, Washington DC: National Council for Science and the Environment

- Jaramillo, Alvaro (2001), "Blackbirds, Orioles and Allies", in Elphick, Chris; Dunning, Jr., John B.; Sibley, David (eds.), The Sibley Guide to Bird Life & Behaviour, London: Christopher Helm, ISBN 978-0-7136-6250-4

- Juniper, Tony; Parr, Mike (2003), Parrots: A Guide to the Parrots of the World, London: Christopher Helm, ISBN 978-0-7136-6933-6

- Kaplan, Gisela (2004), Australian Magpie: Biology and Behaviour of an Unusual Songbird, Melbourne, Victoria: CSIRO Publishing, p. 121, ISBN 978-0-643-09068-2, retrieved 2009-12-16

- Kemp, A. C. (2001), "Family Bucerotidae (Hornbills)", in del Hoyo, Josep; Elliott, Andrew; Sargatal, Jordi (eds.), Handbook of Birds of the World, Volume 6: Mousebirds to Hornbills, Barcelona: Lynx Edicions, ISBN 978-84-87334-30-6

- Petit, Kenneth E.; Petit, Lisa J.; Petit, Daniel R. (1989), "Fecal Sac Removal: Do the Pattern and Distance of Dispersal Affect the Chance of Nest Predation?" (PDF), The Condor, 91 (2): 479–482, doi:10.2307/1368331, JSTOR 1368331

- Reed, J. Michael (2001), "Woodpeckers and Allies", in Elphick, Chris; Dunning, Jr., John B.; Sibley, David (eds.), The Sibley Guide to Bird Life & Behaviour, London: Christopher Helm, ISBN 978-0-7136-6250-4

- Rasmussen, Pamela C.; Collar, Nigel J. (2002), "Family Bucconidae (Puffbirds)", in del Hoyo, Josep; Elliott, Andrew; Sargatal, Jordi (eds.), Handbook of Birds of the World, Volume 7: Jacamars to Woodpeckers, Barcelona: Lynx Edicions, ISBN 978-84-87334-37-5

- Rosenfeld, R.N.; Rosenfeld, A. J.; Gratson, M. W. (1982), "Unusual Nest Sanitation by a Broad-Winged Hawk" (PDF), The Wilson Bulletin, 94 (3): 2365–366

- Rudolph, D. C.; Kyle, H.; Conner, R. N. (1990), "Red-cockaded woodpeckers vs. Rat Snakes: The effectiveness of the resin barrier" (PDF), Wilson Bull., 102 (l): 14–22

- Sabrosky, Curtis W.; Bennett, G. F.; Whitworth, T. L. (1989), Bird blow-flies (Protocalliphora) (Diptera: Calliphoridae) in North America with notes on the Palearctic species, Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press

- Schuetz, Justin G. (2005), "Common waxbills use carnivore scat to reduce the risk of nest predation", Behavioral Ecology, 16 (1): 133–137, doi:10.1093/beheco/arh139

- Seng, William J. (2001), "Flamingos", in Elphick, Chris; Dunning, Jr., John B.; Sibley, David (eds.), The Sibley Guide to Bird Life & Behaviour, London: Christopher Helm, ISBN 978-0-7136-6250-4

- Short, Lester L.; Horne, Jennifer F. M. (2002a), "Family Capitonidae (Barbets)", in del Hoyo, Josep; Elliott, Andrew; Sargatal, Jordi (eds.), Handbook of Birds of the World, Volume 7: Jacamars to Woodpeckers, Barcelona: Lynx Edicions, ISBN 978-84-87334-37-5

- Short, Lester L.; Horne, Jennifer F. M. (2002b), "Family Indicatoridae (Honeyguides)", in del Hoyo, Josep; Elliott, Andrew; Sargatal, Jordi (eds.), Handbook of Birds of the World, Volume 7: Jacamars to Woodpeckers, Barcelona: Lynx Edicions, ISBN 978-84-87334-37-5

- Skowron, C; Kern, M. (1980), "The insulation in nests of selected North-American songbirds", Auk, 97: 816–824

- Ward, P.; Zahavi, A. (1973), "The importance of certain assemblages of birds as "information centers" for food finding", Ibis, 115 (4): 517–534, doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1973.tb01990.x

- Whittow, F.N.; Berger, A.J. (1977), "Heat loss from the nest of the Hawaiian honeycreeper, 'Amakihi'", Wilson Bulletin, 89: 480–483

- Wimberger, P. H. (1984), "The use of green plant material in bird nests to avoid ectoparasites" (PDF), Auk, 101 (3): 615–616, doi:10.1093/auk/101.3.615

- Woodall, Peter F. (2001), "Family Alcedinidae (Kingfishers)", in del Hoyo, Josep; Elliott, Andrew; Sargatal, Jordi (eds.), Handbook of Birds of the World, Volume 6: Mousebirds to Hornbills, Barcelona: Lynx Edicions, ISBN 978-84-87334-30-6

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bird nests. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Nidification. |

.jpg)

.jpg)