Plastination

Plastination is a technique or process used in anatomy to preserve bodies or body parts, first developed by Gunther von Hagens in 1977.[1] The water and fat are replaced by certain plastics, yielding specimens that can be touched, do not smell or decay, and even retain most properties of the original sample.[2]

Process

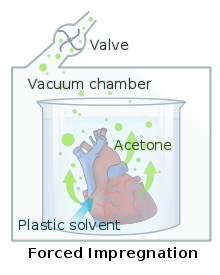

Four steps are used in the standard process of plastination: fixation, dehydration, forced impregnation in a vacuum, and hardening.[3] Water and lipid tissues are replaced by curable polymers, which include silicone, epoxy, and polyester-copolymer.[3]

The first step of plastination, fixation,[4] frequently uses a formaldehyde-based solution, and serves two functions. Dissecting the specimen to show specific anatomical elements can be time consuming. Formaldehyde or other preserving solutions help prevent decomposition of the tissues. They may also confer a degree of rigidity. This can be beneficial in maintaining the shape or arrangement of a specimen. A stomach might be inflated or a leg bent at the knee, for example.

After any necessary dissections have taken place, the specimen is placed in a bath of acetone (freezing point −95° C [-139° F]) at −20° to −30° C (-4 to -22° F). The volume of the bath should be 10 times that of the specimen. The acetone is renewed two times over the course of six weeks. The acetone draws out all the water and replaces it inside the cells.[5]

In the third step, the specimen is then placed in a bath of liquid polymer, such as silicone rubber, polyester, or epoxy resin. By creating a vacuum, the acetone is made to boil at a low temperature. As the acetone vaporizes and leaves the cells, it draws the liquid polymer in behind it, leaving a cell filled with liquid plastic.[5]

The plastic must then be cured with gas, heat, or ultraviolet light, to harden it.[4]

A specimen can vary from a full human body to a small piece of an animal organ, and they are known as 'plastinates'. Once plastinated, the specimens and bodies are further manipulated and positioned prior to curing (hardening) of the polymer chains.

History

In November 1979, Gunther von Hagens applied for a German patent, proposing the idea of preserving animal and vegetable tissues permanently by synthetic resin impregnation.[6] Since then, von Hagens has applied for further US patents regarding work on preserving biological tissues with polymers.[7][8]

With the success of his patents, von Hagens went on to form the Institute for Plastination in Heidelberg, Germany in 1993. The Institute for Plastination, along with von Hagens, made their first showing of plastinated bodies in Japan in 1995, which drew more than three million visitors. The institute maintains three international centres of plastination, in Germany, Kyrgyzstan, and China.[9]

Related preservation methods

Other methods have been in place for thousands of years to halt the decomposition of the body. Mummification used by the ancient Egyptians is a widely known method which involves the removal of body fluid and wrapping the body in linens. Prior to mummification, Egyptians would lay the body in a shallow pit in the desert and allow the sun to dehydrate the body.[10]

Formalin, an important solution to body preservation, was introduced in 1896 to help with body preservation. Soon to follow formalin, color-preserving embalming solutions were developed to preserve life-like color and flexibility to aid in the study of the body.[11]

Paraffin impregnation was introduced in 1925, and the embedding of organs in plastic was developed in the 1960s.

Body preservation methods current to the 21st century are cryopreservation, which involves the cooling of the body to very low temperatures to preserve the body tissues, plastination, and embalming.[12]

Other methods used in modern times include the Silicone S 10 Standard Procedure, the Cor-Tech Room temperature procedure, the Epoxy E 12 procedure, and the Polyester P 35 (P 40) procedure.[13] The Silicone S 10 is the procedure most often used in plastination and creates opaque, natural-looking specimen.[14] Dow Corning Corporation's Cor-Tech Room Temperature Procedure is designed to allow plastination of specimen at room temperature to various degrees of flexibility using three combinations of polymer, crosslinker, and catalyst.[15] According to the International Society for Plastination, the Epoxy E 12 procedure is used "for thin, transparent, and firm body and organ slices", while the Polyster P 35 (P 40) preserves "semitransparent and firm brain slices".[13] Samples are prepared for fixation through the first method by deep freezing,[16] while the second method works best following 4–6 weeks of preparation in a formaldehyde mixture.[17]

Uses of plastinated specimens

Plastination is useful in anatomy, serving as models and teaching tools.[18] It is used at more than 40 medical and dental schools throughout the world as an adjunct to anatomical dissection.

Students enrolled in introductory animal science courses at many universities learn animal science through collections of multispecies large-animal specimens. Plastination allows students to have hands-on experience in this field, without exposure to chemicals such as formalin. For example, plastinated canine gastrointestinal tracts are used to help in the teaching of endoscopic technique and anatomy.[19] The plastinated specimens retain their dilated conformation by a positive pressure air flow during the curing process, which allows them to be used to teach both endoscopic technique and gastrointestinal anatomy.

With the use of plastination as a teaching method of animal science, fewer animals have to be killed for research, as the plastination process allows specimens to be studied for a long time.[20]

TTT sheet plastinates for school teaching and lay instruction provide a thorough impression of the complexity of an animal body in just one specimen.

North Carolina State University's College of Veterinary Medicine in Raleigh, North Carolina, uses both plastic coating (PC) and plastination (PN) to investigate and compare the difference in the two methods. The PC method was simple and inexpensive, but the PN specimens were more flexible, durable, and life-like than those preserved by the PC method. The use of plastination allowed the use of many body parts such as muscle, nerves, bones, ligaments, and central nervous system to be preserved.[21]

The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio was the first school in the United States to use this technique to prepare gross organ specimens for use in teaching.[22] The New York University College of Dentistry.,[18] Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine,[23] University of Warwick, and University of Northumbria [24] use collections of plastinates as teaching aids. The University of Vienna has its own plastination laboratory.[25]

Ethical concerns

Concern over consent of bodies being used in the plastination process has arisen. Over 20 years ago, von Hagens set up a body donation program in Germany and has signed over 9,000 donors into the plastinate program: 531 have already died. The program has reported an average of one body a day being released to the plastination process. About 90% of the donors registered are German. Von Hagens' body donations are now being managed by the Institute for Plastination (IfP)[26] established in 1993.[27]

Religious opposition

A number of religious sects prohibit organ donation.[28][29] Ultra-Orthodox Jews oppose post mortem organ donation, and have tried to pass laws against unclaimed cadavers being used in research.[30] A number of religious organizations, including Catholic[31][32] and Jewish[33] ones, object to the display of plastinated body parts at public exhibitions.

Plastination exhibitions

For the first 20 years, plastination was used to preserve small specimens for medical study. In the early 1990s, the equipment was developed to make plastinating whole body specimens possible, each specimen taking up to 1,500 man-hours to prepare.[34] The first exhibition of whole bodies was displayed by von Hagens in Japan in 1995.

Over the next two years, Von Hagens developed the Körperwelten (Body Worlds) public exhibitions, showing whole bodies plastinated in life-like poses and dissected to show various structures and systems of human anatomy. The earliest exhibitions were presented in the Far East and in Germany, and Gunther von Hagens' exhibitions have subsequently been hosted by museums and venues in more than 50 cities worldwide, attracting more than 29 million visitors..

Gunther von Hagens' Body Worlds exhibitions are the original, precedent-setting public anatomical exhibitions of real human bodies, and the only anatomical exhibits that use donated bodies, willed by donors to the Institute for Plastination for the express purpose of serving the Body Worlds mission to educate the public about health and anatomy. To date, more than 10,000 people have agreed to donate their bodies to Institute for Plastination.[26]

In 2004, Premier Exhibitions began their "Bodies Revealed" exhibition in Blackpool, England, which ran from August through October 2004. In 2005 and 2006, the company opened their "Bodies Revealed" and "Bodies...The Exhibition" in Seoul, Tampa, and New York City. The West Coast exhibition site opened on 22 June 2006 at the Tropicana Resort and Casino Las Vegas. As of June 2009, BODIES... The Exhibition is showing at the Ambassador Theatre (Dublin) in Dublin, Ireland.[35] The exhibition was in Istanbul, Turkey, until the end of March 2011.

Plastination galleries are offered in several college medical schools, including the University of Michigan (said to possess the nation's largest such lab)[36], Vienna University[37], and the JSS Medical College[38] Gunther von Hagens maintains a permanent exhibition of plastinates and plastination at the Plastinarium in Guben, Germany.[39]

Additional images

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to plastination. |

See also

- Freeze drying

- Écorché

References

- "The Idea behind plastination". Institute for Plastination. 2006. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- Weiglein, A. H. (2005). "Overview & General Principles of the Plastination Procedures". 8th Interim Conf Plast. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 27 January 2009.

- von Hagens, Gunther; Klaus Tiedemann; Wilhelm Kriz (1987). "The current potential of plastination". Anatomy and Embryology. 175 (4): 411–21. doi:10.1007/BF00309677. PMID 3555158.

- Henry, Robert W.; Larry Janick; Francis Paul Salmos (February 1997). "Specimen preparation for silicone plastination" (PDF). Journal of the International Society for Plastination. 12 (1). ISSN 1090-2171. Retrieved 27 January 2009.

- Bickley, Harmon C.; Robert S. Conner, Anna N. Walker and R. Lamar Jackson (January 1987). "Preservation of tissue by silicone rubber impregnation" (PDF). Journal of the International Society for Plastination. 1 (1): 30–39. ISSN 1090-2171. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 June 2015. Retrieved 10 May 2009.

- DE patent 2710147, "Präparat aus biologischen verweslichen Objekten und Verfahren zu ihrer Herstellung", issued 14 September 1978

- US patent 4205059, "Animal and vegetal tissues permanently preserved by synthetic resin", issued 27 May 1980

- US patent 4320157, "Method for preserving large sections of biological tissue with polymers", issued 16 March 1982

- "Preservation by Plastination". BIODUR. Retrieved 5 March 2009.

- Rymer, Eric. "History of Burial Beliefs in Ancient Egypt". History Link 101. Retrieved 11 May 2009.

- "Formaldehyde: Its Development And History Since 1868" (PDF). Museum of Funeral Customs. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 March 2005. Retrieved 11 May 2009.

- US patent 5089288, "Method for Impregnating Tissue Samples in Paraffin", issued 18 February 1992

- "Other Plastination Methods". International Society for Plastination. 20 October 1998. Archived from the original on 15 May 2009. Retrieved 19 May 2009.

- "The Silicone S 10". International Society for Plastination. 2008. Retrieved 19 May 2009.

- "The COR-TECH Room Temperature". International Society for Plastination. 2008. Retrieved 19 May 2009.

- "The Epoxy E 12". International Society for Plastination. 2008. Retrieved 19 May 2009.

- "The Polyester P35/P40". International Society for Plastination. 2008. Retrieved 19 May 2009.

- "Life, Death, and One Man's Quest to Demystify the Inner Realms of the Human Body". Nexus. Fall 2004. Retrieved 13 February 2009.

- Janick, L.; R. C. DeNovo; R. W. Henry (1997). "Plastinated Canine Gastrointestinal Tracts Used to Facilitate Teaching of Endoscopic Technique and Anatomy". Cells Tissues Organs. 158 (1): 48–53. doi:10.1159/000147910. PMID 9293297.

- "KSUCVM Plastination Laboratory". Vet.ksu.edu. 8 January 2009. Retrieved 18 March 2010.

- Holladay SD, Hudson LC (1989). "Use of plastinated brains in teaching neuroanatomy at the North Carolina State University, College of Veterinary Medicine" (PDF). Journal of the International Society for Plastination. 3 (1): 15–17. Retrieved 19 May 2009.

- "Pathology Academic Resource Center: UT Health Science Center - Graduate School of Biomedical Science". pathology.uthscsa.edu. Retrieved 22 September 2010.

- "Virtual Campus Tour: PCOM Anatomy Lab". PCOM.edu. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- "First University to Acquire von Hagens Plastinations for University Teaching". European-hospital.com. 28 October 2008. Retrieved 18 March 2010.

- "Vienna University Plastination Facility". Meduniwien.ac.at. Retrieved 18 March 2010.

- "Institute". Bodyworlds.com. Retrieved 18 March 2010.

- Singh, Debashis; Von Hagens, G (March 2003). "Scientist or showman?". BMJ. 326 (7387): 468. doi:10.1136/bmj.326.7387.468. PMC 1125369. PMID 12609939.

- https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1705993-overview

- https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/health-and-families/features/life-after-death-donating-your-body-for-research-1623676.html

- http://www.nydailynews.com/news/politics/exclusive-2-pols-change-unclaimed-cadaver-law-article-1.2165881

- KTVI (28 August 2007). "No Body World Exhibit For Catholic Field Trips". Fox Television Stations. Archived from the original on 23 June 2008. Retrieved 17 September 2008.

- Archdiocese of Vancouver – Body Worlds Exhibit Archived 13 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- DEBORAH SUSSMAN SUSSER Associate Editor (9 February 2007). "'Body Worlds' comes to Phoenix – Jewish News of Greater Phoenix". Jewishaz.com. Retrieved 25 February 2010.

- Chambless, Ross (19 September 2008). "TheLeonardo Podcast no. 1" (MP3). Retrieved 8 May 2009.

- ..

- "Plastination". Med.umich.edu. Retrieved 18 March 2010.

- "Plastination at the Vienna University". Meduniwien.ac.at. Retrieved 18 March 2010.

- https://www.jssuni.edu.in/JSSWeb/WebShowFromDB.aspx?MODE=SSMD&PID=10002&CID=4&DID=8&MID=0&SMID=10402. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "The PLASTINARIUM-What is it?". www.plastinarium.de. Gubener Plastinate GmbH. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

Further reading

- von Hagens, Gunther (March 1986). Heidelberg plastination folder: collection of technical leaflets of plastination. Heidelberg: Biodur Products. OCLC 256499636. First published as von Hagens, Gunther (1985). Heidelberger Plastinationshefter Sammlung von Merkblättern zur Plastination (in German). Heidelberg: University of Heidelberg. OCLC 174501422.

- da Fonseca, Liselotte Hermes; Thomas Kliche (2007). "Verführerische Leichen – verbotener Verfall. "Körperwelten" als gesellschaftliches Schlüsselereignis. Perspektiven Politischer Psychologie". Deutsches Ärzteblatt (in German). 104 (38).

- von Hagens, Gunther; Klaus Tiedemann; Wilhelm Kriz (March 1987). "The current potential of plastination". Anatomy and Embryology. 175 (4): 411–21. doi:10.1007/BF00309677. PMID 3555158.

- Whalley, Angelina (2005). Pushing the Limits: Encounters with Body Worlds Creator Gunther von Hagens. Heidelberg: Arts & Sciences. ISBN 978-3-937256-07-8. OCLC 61119531.

- von Hagens, Gunther (2006). Body Worlds The Anatomical Exhibition of Real Human Bodies. Heidelberg: Institute für Plastination. ISBN 978-3-937256-04-7. OCLC 69257041.

- Ottone NE et al (2015). New contributions to the development of a plastination technique at room temperature with silicone. Anatomical Science International 2015; 90(2):126-35. doi: 10.1007/s12565-014-0258-6

- Ottone NE et al (2018). E12 sheet plastination: Techniques and applications. Clinical Anatomy, 31(5):742-756. doi: 10.1002/ca.23008

- Ottone NE et al (2020). Extraction of DNA from plastinated tissues. Forensic Science International, 309:110199. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2020.110199

- Ottone NE (2020). Micro-Plastination. Technique for Obtaining Slices below 250 µm for the Visualization of Microanatomy in Morphological and Pathological Morphology Protocols. International Journal of Morphology, 38( 2 ): 389-91. doi: 10.4067/S0717-95022020000200389

External links

- Plastination technique, on Body Worlds page

- Plastination website by Dr. Selcuk Tunali

- Laboratory of Plastination & Anatomical Techniques, Universidad de La Frontera, Temuco, Chile (Dr. Nicolas E. Ottone)

- Plastination Models Inc.

- Discovery, March 2004, 'Gross Anatomy by Alan Burdick'

- Plastination in India by Dr. N. M. Shama Sundar.

- Plastination: Silicone Impregnation of Specimens (the standard S10 technique)

- Plastination: The Sheet Plastination Technique

- International Society for Plastination

- The New Plastination Index Online

- The New Plastination Index on-line: Subject Index

- "Exhibit Human" a documentary on plastination by Aaron Edell

- Learn About PCOM's Plastination Process