Muqarnas

Muqarnas (Arabic: مقرنص; Persian: مقرنس), known in Iranian architecture as Ahoopāy (Persian: آهوپای) and in Iberian architecture as Mocárabe, is a form of ornamented vaulting in Islamic architecture. It is the archetypal form of Islamic architecture, integral to the vernacular of Islamic buildings.[1] The muqarnas structure originated from the squinch. Sometimes called "honeycomb vaulting"[2] or "stalactite vaulting", the purpose of muqarnas is to create a smooth, decorative zone of transition in an otherwise bare, structural space. This structure gives the ability to distinguish between the main parts of a building, and serve as a transition from the walls of a room into a domed ceiling.[3]

Muqarnas is significant in Islamic architecture because its elaborate form is a symbolic representation of universal creation by God. Muqarnas architecture is featured in domes, half-dome entrances, iwans and apses. The two main types of muqarnas are the North African/Middle Eastern style, composed of a series of downward triangular projections, and the Iranian style, composed of connecting tiers of segments.[4]

Etymology

The etymology of the word muqarnas is somewhat vague. It is thought to have originated from the Greek word korōnis meaning "ornamental molding".[5] There is also speculation of the origin to stem from the Arabic word qarnasi meaning "intricate work".[6]

Structure

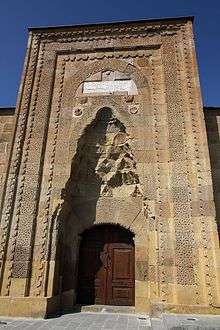

Muqarnas is typically applied to the undersides of domes, pendentives, cornices, squinches, arches and vaults and is often seen in the mihrab of a mosque.[7] They can be entirely ornamental, or serve as load-bearing structures. The earliest forms of muqarnas domes, found in the Mesopotamian region, were primarily structural. Muqarnas grew increasingly common and decorative in the beginning of the 12th century. Muqarnas can either be carved into the structural blocks of corbelled vaulting or hung from a structural roof as a purely decorative surface.[8][9] The most distinctive form of the muqarnas is the honeycomb structure, often intricate and impossibly fractal-like in its complexity. The individual cells are called alveoles.[10] Muqarnas can range from seemingly simplistic to incredibly complex blends of architecture, mathematics, and art. Two rare examples of artful sciography using pareidolia are found over the entrances of Divriği Great Mosque and Hospital,[11] Divriği, Turkey, and of the Niğde Alaaddin Mosque[12][13][14] in Niğde, Turkey.

Muqarnas are made of brick, stone, stucco, or wood, and clad with tiles or plaster. The form and medium vary depending on the region they are found. Muqarnas structure in the east are built using a standard set of components and guidelines, creating a more uniformed style. Muqarnas found in the west are more intricately creative because they tend to not have a standard set of regulations regarding composition, components, and construction.[15] In Syria, Egypt, and Turkey, muqarnas are constructed out of stone. In North Africa, they are typically constructed from plaster and wood, and in Iran and Iraq, the muqarnas dome is built with bricks covered in plaster or ceramic clay.[5]

Origin

The origin of the muqarnas can be traced back to the mid-tenth century in northeastern Iran and central North Africa,[16] as well as the Mesopotamian region.[1] The exact origins of muqarnas are unknown, but it is assumed to have originated in either of these regions and dispersed through trade and pilgrimage. Evidence from 10th-century architectural fragments found near Nishapur in Iran, and tripartite squinches located in the Arab-Ata Mausoleum in the village of Tim, near Samarkand in Uzbekistan, are some examples of early developmental forms of muqarnas.[17]

Qubba Imam al-Dawr in Iraq, completed in 1090, was the first concrete example of a muqarnas dome.[17] The shrine was reported destroyed by ISIS in October 2014.[18]

Given the advanced technical mastery of constructing muqarnas, it is believed that the technique, and therefore architectural elements, were imported into Egypt from elsewhere in the empire. Scholars speculate the outside influence originated from Syria; however, there are few Syrian monuments still standing that can support this claim.[3]

In Egypt, the Aswan Mausolea is a crucial example for the advancement in the development of the stalactite pendentive. In the mid-eleventh century, prosperous pilgrimage routes along the Red Sea and flourishing trade routes began in Cairo and dispersed throughout the Islamic empire. This allowed for a great exchange of ideas as well as a lucrative economy, capable of funding various architectural projects.[3]

.jpg)

The largest example of muqarnas domes can be found in Iraq and the Jazira region of eastern Syria, with a diverse variety of applications in domes, vaults, mihrabs, and niches.[17] These domes are dated around the mid-twelfth century, the time of the Mongol invasion – a period of great architectural activity.[17]

Prominent examples of their development can be found in the minaret of Badr al-Jamali's mashhad in Cairo, dated by inscription to 1085, a cornice in Cairo's north wall (1085), the Jameh Mosque of Isfahan (1088), the Almoravid Qubba (1107–43) in Marrakech, the Great Mosque of Tlemcen in Algeria (1136), the Mosque of the Qarawiyyin in Morocco (rebuilt between 1135 and 1140), the Bimaristan of Nur al-Din in Damascus (1154),[3][17] the Alhambra in Granada, Spain, the Abbasid palaces in Baghdad, Iraq, and the mausoleum of Sultan Qaitbay, Cairo, Egypt. Large rectangular roofs in wood with muqarnas-style decoration adorn the 12th-century Cappella Palatina in Palermo, Sicily, and other important buildings in Norman Sicily. Muqarnas ornament is also found in Armenian architecture.

Significance

Muqarnas ornament is significant in Islamic architecture because it represents an ornamental form that conveys the vastness and complexity of Islamic ideology. The distinct units of the dome represent the complex creation of the universe, and in turn the Creator, himself. The elaborate nature of the stacked domes also serve as a representation of heaven. Influenced by the theology of the Greek Atomist Theory, it was believed that every atom composing a muqarnas dome was connected with God. The astonishing ability for the extremely complex and seemingly unsupported muqarnas dome was proof of the mysterious existence of the universe.[17]

The muqarnas domes were often constructed above portals of entry for the purpose of establishing a threshold between two worlds. The celestial connotation of the muqarnas structure represents a passage from "the functions of living, or of awaiting eternal life that is expressed by geometric forms."[19] When featured in the interior of domes, the viewer would look upward (towards heaven) and contemplate its beauty. Conversely, the downward hanging structures of the muqarnas represented God's presence over the physical world.

Gallery

High-resolution detail of Mocárabe from the Alhambra, showing horizontal courses; the clearer one zigzags across at about 1/3 of the way down.

High-resolution detail of Mocárabe from the Alhambra, showing horizontal courses; the clearer one zigzags across at about 1/3 of the way down.- Medieval architect's plan of two muqarnas vaults, from the Topkapı Scroll

.jpg) Corbelled vault carved into muqarnas, showing method of suspension for pendant points

Corbelled vault carved into muqarnas, showing method of suspension for pendant points Amber Fort, near Jaipur. The marble palace Jai Mandir. Sheesh Mahal, Hall of Mirrors

Amber Fort, near Jaipur. The marble palace Jai Mandir. Sheesh Mahal, Hall of Mirrors Muqarnas corbel, Qutb Minar, India

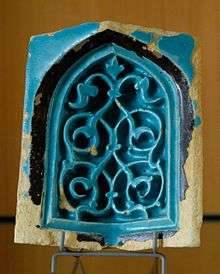

Muqarnas corbel, Qutb Minar, India Muqarnas, single aveole. Earthenware with molded decoration under opaque turquoise glaze, Timurid art, 1st half of the 15th century. From the Shah-i-Zinda in Samarkand.

Muqarnas, single aveole. Earthenware with molded decoration under opaque turquoise glaze, Timurid art, 1st half of the 15th century. From the Shah-i-Zinda in Samarkand.- Mocárabe stalactite work on the underside of an arch, Alhambra Palace, Granada, Spain, with downward-projecting "stalactites"

- Painted muqarnas, Palatine Chapel, Palermo, commissioned by Roger II of Sicily in 1132

Gilded tile muqarnas at Chehel Sotoon Palace (17th century), Isfahan

Gilded tile muqarnas at Chehel Sotoon Palace (17th century), Isfahan Muqarna in Tangiers, Morocco

Muqarna in Tangiers, Morocco Muqarnas in Fez, Morocco

Muqarnas in Fez, Morocco.jpg) Upward- and downward-facing muquarnas

Upward- and downward-facing muquarnas

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Muqarnas. |

- Architecture of Iran

- Islamic geometric patterns

- Mathematics and art

- Ottoman architecture

References

- Stephennie, Mulder (2014). The Shrines of the 'Alids in Medieval Syria : sunnis, shi'is and the architecture of coexistence. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 9780748645794. OCLC 929836186.

- VirtualAni website. "Armenian architecture glossary". Retrieved 2009-07-17.

- Bloom, Jonathan M. (1988). "The Introduction of the Muqarnas into Egypt". Muqarnas. 5: 21–28. doi:10.2307/1523107. JSTOR 1523107.

- "Muqarnas | School of Islamic Geometric Design". Retrieved 2018-12-12.

- Garofalo, Vincenza (2010). "A Methodology for Studying Muqarnas: The Extant Examples in Palermo". Muqarnas. 27: 357–406. doi:10.1163/22118993_02701014. JSTOR 25769702.

- Bloom, Jonathan M. (1988). "The Introduction of the Muqarnas into Egypt". Muqarnas. 5: 21–28. doi:10.2307/1523107. JSTOR 1523107.

- Curl, James Stevens (2006). A Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture (Paperback) (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-860678-9.

- sharmiarchitect (2013-09-10). "Muqarnas - Mathematics in Islamic Architecture". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Dan Owen (2014-01-16). "Muqarnas مقرنس Reconceived - A Brief Survey". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Armenian Architecture - VirtualANI - Glossary". www.virtualani.org. Retrieved 2018-12-12.

- https://duckduckgo.com/?q=divrigi+ulu+camii+namaz+kilan+insan&t=h_&iax=1&ia=images&iai=http%3A%2F%2Fi.milliyet.com.tr%2FSonDakikaHaberGaleriler%2F2014%2F07%2F13%2Fdivrigi-ulu-camii-de-namaz-kilan-insan-silueti-4570616.Jpeg Divriği Great Mosque and Hospital with the silhouette of a praying man that appears over either entrance door of the mosque part and changes pose as the sun moves.

- "Niğde Alaaddin Camii 'nin Kapısındaki Kadın Silüetinin Sırrı?". Nevşehir Kentrehberim (in Turkish). 2011. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- "Camiler, ALÂEDDİN CAMİ". Kültür ve Turizm Bakanlığı (in Turkish). Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- "HISTORICAL MONUMENTS OF NIGDE". World Heritage Academy. 2013. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- Alkadi, Rana Munir; Gonzalo, José Carlos Palacios (2018-04-01). "Muqarnas Domes and Cornices in the Maghreb and Andalusia". Nexus Network Journal. 20 (1): 95–123. doi:10.1007/s00004-017-0367-3. ISSN 1522-4600.

- "Encyclopedia.com | Free Online Encyclopedia". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2018-12-12.

- Tabbaa, Yasser (1985). "The Muqarnas Dome: Its Origin and Meaning". Muqarnas. 3: 61–74. doi:10.2307/1523084. ISSN 0732-2992. JSTOR 1523084.

- "Qubba Imam al-Dur". Archnet. Retrieved 2018-12-12.

- Brett, David; Grabar, Oleg (1993). "The Mediation of Ornament". Circa (65): 63. doi:10.2307/25557837. ISSN 0263-9475. JSTOR 25557837.

External links

- Muqarnas : A Three-dimensional Decoration of Islam Architecture. Contains a database of over a thousand plans of extant muqarnas, indexed by location and geometry.

- Abstract, Nexus 2004, Muqarnas, Construction and Reconstruction

- Informative page about muqarnas from the School of Islamic Geometric Design

- polygonal computer models

- Page with VRML interactive 3D models

- Slideshow on muqarnas geometry, with traditional and computer-assisted new designs.

.jpeg)

.jpg)