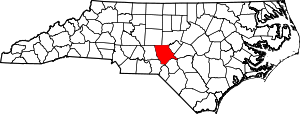

Moore County, North Carolina

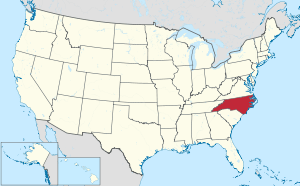

Moore County is a county located in the U.S. state of North Carolina. As of the 2010 census, the population was 88,247.[1] Its county seat is Carthage[2] and its largest town is Pinehurst. It is a border county between the Piedmont and the Atlantic Coastal Plain.

Moore County | |

|---|---|

Moore County Courthouse, in Carthage | |

Location within the U.S. state of North Carolina | |

North Carolina's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 35°19′N 79°29′W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | 1784 |

| Named for | Alfred Moore |

| Seat | Carthage |

| Largest village | Pinehurst |

| Area | |

| • Total | 706 sq mi (1,830 km2) |

| • Land | 698 sq mi (1,810 km2) |

| • Water | 8.0 sq mi (21 km2) 1.1%% |

| Population | |

| • Estimate (2019) | 100,880 |

| • Density | 126/sq mi (49/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| Congressional district | 8th |

| Website | www |

In the early years the economy was dependent on agriculture and lumber. The lumber business expanded after railroads reached the area, improving access to markets. It lies at the northern edge of the area known as the Sandhills region, and developed resorts in the late 19th century, aided by railroads.

Since the early 21st century Moore County comprises the Aberdeen-Pinehurst-Southern Pines, North Carolina Micropolitan Statistical Area. It is sometimes included in the Research Triangle and Greater Raleigh-Durham CSA.

History

Indigenous peoples occupied this area, with varying cultures over thousands of years. In the historic period that included European encounter, tribes included Algonquian speakers in the coastal area, with Siouan-speaking tribes in the border and Piedmont, and the Iroquoian-speaking Cherokee in the western mountains.

This area was settled by Highland Scots and descendants, who had migrated through the backcountry of Pennsylvania and Virginia. The county was formed in 1785, shortly after the American Revolutionary War, from part of Cumberland County. It was named after Alfred Moore, an officer in the American Revolutionary War and associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States.

In 1907 parts of Moore and Chatham counties were combined to form Lee County.

Moore County has many golf resorts in the Southern Pines/Pinehurst area, and hosted the 1996 and 2001 Women's U.S. Opens, as well as the 1999 and 2005 Men's U.S. Opens. The Women's Open returned to Southern Pines in 2007. In 2014, they consecutively hosted both the Women's and Men's Opens in the same year, a first in U.S. Open history.[3]

Celebrities who frequent or have private homes in the area include athletes Michael Jordan, Tiger Woods, and Jack Nicklaus, and British actor Sean Connery. Past residents of the area have included Annie Oakley, Harvey Firestone, General George C. Marshall, and John D. Rockefeller.

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 706 square miles (1,830 km2), of which 698 square miles (1,810 km2) is land and 8.0 square miles (21 km2) (1.1%) is water.[4]

Adjacent counties

- Chatham County - north

- Lee County - northeast

- Harnett County - east

- Cumberland County - southeast

- Hoke County - southeast

- Scotland County - south

- Richmond County - southwest

- Montgomery County - west

- Randolph County - north

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1790 | 3,870 | — | |

| 1800 | 4,767 | 23.2% | |

| 1810 | 6,367 | 33.6% | |

| 1820 | 7,128 | 12.0% | |

| 1830 | 7,745 | 8.7% | |

| 1840 | 7,988 | 3.1% | |

| 1850 | 9,342 | 17.0% | |

| 1860 | 11,427 | 22.3% | |

| 1870 | 12,040 | 5.4% | |

| 1880 | 16,821 | 39.7% | |

| 1890 | 20,479 | 21.7% | |

| 1900 | 23,622 | 15.3% | |

| 1910 | 17,010 | −28.0% | |

| 1920 | 21,388 | 25.7% | |

| 1930 | 28,215 | 31.9% | |

| 1940 | 30,969 | 9.8% | |

| 1950 | 33,129 | 7.0% | |

| 1960 | 36,733 | 10.9% | |

| 1970 | 39,048 | 6.3% | |

| 1980 | 50,505 | 29.3% | |

| 1990 | 59,013 | 16.8% | |

| 2000 | 74,769 | 26.7% | |

| 2010 | 88,247 | 18.0% | |

| Est. 2019 | 100,880 | [5] | 14.3% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[6] 1790-1960[7] 1900-1990[8] 1990-2000[9] 2010-2013[1] | |||

As of the census[10] of 2010, there were 88,247 people, 34,625 households, and 21,959 families residing in the county. The population density was 107 people per square mile (41/km²). There were 44,468 housing units at an average density of 50 per square mile (19/km²). The racial makeup of the county was 82.8% White, 13.4% Black or African American, 0.9% Native American, 1.0% Asian, 0.2% Pacific Islander, 2.20% from other races, and 0.88% from two or more races. 6.1% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

By 2005 78.0% of the county population was non-Hispanic whites. 5.1% of the population was Latino. 14.8% of the population was African-American.

There were 30,713 households out of which 26.70% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 58.10% were married couples living together, 10.20% had a female householder with no husband present, and 28.50% were non-families. 24.90% of all households were made up of individuals and 11.30% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.38 and the average family size was 2.81.

In the county, the population was spread out with 21.2% under the age of 18, 6.60% from 18 to 24, 25.80% from 25 to 44, 23.80% from 45 to 64, and 23.4% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 42 years. For every 100 females there were 93.00 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 89.80 males.

The median income for a household in the county was $48,348, and the median income for a family was $48,492. Males had a median income of $31,260 versus $23,526 for females. The per capita income for the county was $23,377. About 8.00% of families and 11.40% of the population were below the poverty line, including 16.60% of those under age 18 and 10.10% of those age 65 or over.

Communities

City

Towns

- Aberdeen

- Cameron

- Carthage (county seat)

- Pinebluff

- Southern Pines

- Taylortown

- Vass

Villages

Census-designated places

Unincorporated communities

Townships

The county is divided into ten townships, which are both numbered and named:

- 1 (Carthage)

- 2 (Bensalem)

- 3 (Sheffields)

- 4 (Ritter)

- 5 (Deep River)

- 6 (Greenwood)

- 7 (McNeill)

- 8 (Sandhill)

- 9 (Mineral Springs)

- 10 (Little River)

Politics, law and government

Since the late 1960s and the civil rights movement and other cultural changes, Moore has become a supporter of Republican presidential candidates. It was one of the first counties east of the Blue Ridge to turn Republican, having supported the GOP nominee in all but one election from 1952 onward. The last Democrat to carry the county was Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964, and Jimmy Carter in 1980 was the last to reach forty percent of the vote. The Republican Party also dominates many local and state elections in majority-white precincts and districts.

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 62.6% 30,490 | 33.5% 16,329 | 3.9% 1,873 |

| 2012 | 63.6% 29,495 | 35.6% 16,505 | 0.9% 415 |

| 2008 | 60.3% 27,314 | 38.9% 17,624 | 0.9% 390 |

| 2004 | 64.4% 24,714 | 35.3% 13,555 | 0.3% 113 |

| 2000 | 63.5% 19,882 | 35.9% 11,232 | 0.6% 187 |

| 1996 | 55.7% 14,760 | 37.2% 9,847 | 7.1% 1,872 |

| 1992 | 46.8% 12,448 | 36.3% 9,649 | 16.9% 4,494 |

| 1988 | 65.4% 14,543 | 34.4% 7,642 | 0.3% 63 |

| 1984 | 67.4% 14,681 | 32.4% 7,063 | 0.2% 38 |

| 1980 | 53.7% 10,158 | 42.8% 8,084 | 3.5% 669 |

| 1976 | 50.5% 7,577 | 49.1% 7,373 | 0.5% 70 |

| 1972 | 70.7% 9,406 | 27.3% 3,627 | 2.1% 275 |

| 1968 | 43.7% 5,322 | 29.5% 3,583 | 26.8% 3,263 |

| 1964 | 44.7% 5,162 | 55.3% 6,384 | |

| 1960 | 51.2% 5,815 | 48.8% 5,548 | |

| 1956 | 52.6% 5,238 | 47.5% 4,729 | |

| 1952 | 51.8% 5,442 | 48.2% 5,066 | |

| 1948 | 40.3% 2,719 | 49.5% 3,341 | 10.2% 690 |

| 1944 | 41.8% 2,663 | 58.2% 3,711 | |

| 1940 | 37.4% 2,587 | 62.6% 4,330 | |

| 1936 | 35.7% 2,481 | 64.3% 4,466 | |

| 1932 | 36.2% 2,459 | 63.1% 4,287 | 0.7% 47 |

| 1928 | 55.5% 3,290 | 44.5% 2,639 | |

| 1924 | 41.3% 1,974 | 57.9% 2,771 | 0.8% 38 |

| 1920 | 46.0% 2,279 | 54.0% 2,679 | |

| 1916 | 43.5% 1,047 | 55.6% 1,337 | 0.9% 22 |

| 1912 | 11.9% 252 | 55.2% 1,167 | 32.9% 695 |

Moore County is a member of the regional Triangle J Council of Governments. In the North Carolina House of Representatives, Moore County lies chiefly in the 52nd District, represented by Republican Deputy Majority Whip James L. Boles Jr. The northwestern part of the county lies within the 78th District, which also covers the southeastern part of Randolph County and is represented by Republican Allen McNeill. In the North Carolina Senate, Moore County lies entirely within the 29th Senate District represented by Majority Whip Jerry W. Tillman.

The North Carolina Department of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention previously operated the Samarkand Youth Development Center (YDC), a correctional facility for delinquent girls, in Eagle Springs. The 60-acre (24 ha) complex first opened in 1918 and did not have a fence.[12]

Attractions and places of interest

- Fort Bragg, a large military installation centered in neighboring Cumberland County, also has portions in Moore County.

- Occoneechee Scout Reservation, site of Camp Durant (with facilities) and Camp Reeves (primitive) campgrounds. Located 9 miles west of Carthage.

- Pinehurst Race Track, a horse-racing track

- Pinehurst Resort, historic golf resort

- Moore County Courthouse, historic Renaissance Revival courthouse building located in Carthage

- Pottery Road, extending from Randolph County, known for a large number of potteries.

- Weymouth Woods-Sandhills Nature Preserve, located near Southern Pines.

Notable residents

- Charles Brady (1951- 2006), was raised here. He became a physician, career Navy officer, and NASA astronaut.

- John Edwards, politician, US Senator and former presidential candidate was raised here

- Jeff Hardy and Matt Hardy, brothers, were raised here; they are wrestlers currently working in the WWE -The Hardy Boyz

- Shannon Moore, was raised here; he is a wrestler currently working in the Independent Circuit.

References

- "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 27, 2013.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- 2014 US Open Championship

- "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Archived from the original on January 12, 2015. Retrieved January 18, 2015.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved June 9, 2017.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 18, 2015.

- "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved January 18, 2015.

- Forstall, Richard L., ed. (March 27, 1995). "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 18, 2015.

- "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. April 2, 2001. Retrieved January 18, 2015.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved 2018-03-16.

- "Samarkand YDC" (Archive). North Carolina Department of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. April 28, 2006. Retrieved on December 16, 2015.