Microfoundations

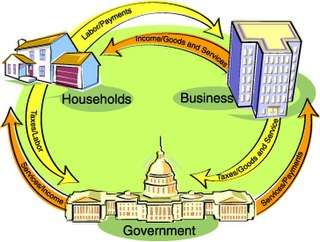

In economics, the microfoundations are the microeconomic behaviors of individual agents, such as households or businesses, on which an economic theory is based.[1][2]

Most early macroeconomic models, including early Keynesian models, were based on hypotheses about relationships between aggregate quantities, such as aggregate production, employment, consumption, and investment. Critics and proponents of these models disagreed as to whether these aggregate relationships were consistent with the principles of microeconomics.[3] Therefore, during recent decades macroeconomists have attempted to combine microeconomic models of household and business behavior to derive the relationships between macroeconomic variables. Presently, many macroeconomic models, representing different theories,[4] are derived by aggregating microeconomic models allowing economists to test them with both macroeconomic and microeconomic data. The study of microfoundations is gaining popularity even outside the field of economics, recent development includes operation management and project studies.[5]

History

Critics of the Keynesian doctrine of macroeconomics soon argued that some of Keynes' assumptions were inconsistent with standard microeconomics. For example, Milton Friedman's microeconomic theory of consumption over time (the 'permanent income hypothesis') suggested that the marginal propensity to consume (the increase of consumer spending with increased income) due to temporary income, which is crucial for the Keynesian multiplier, was likely to be much smaller than Keynesians assumed. For this reason, many empirical studies have attempted to measure the marginal propensity to consume,[1] and macroeconomists have also studied alternative microeconomic models (such as models of credit market imperfections and precautionary saving) that might imply a greater marginal propensity to consume.[6]

One particularly influential endorsement of the study of microfoundations was Robert Lucas, Jr.'s critique of traditional macroeconometric forecasting models. After the apparent shift of the Phillips curve relationship during the 1970s, Lucas argued that the correlations between aggregate variables observed in macroeconomic data would tend to change whenever macroeconomic policy changed. This implied that microfounded models are more appropriate for predicting the effect of policy changes, using the assumption that changes of macroeconomic policy do not alter the microeconomics of the macroeconomy.[7]

Controversy

Some, such as Alan Kirman[8] and S. Abu Turab Rizvi,[9] argue on the basis of the Sonnenschein–Mantel–Debreu theorem that the microfoundations project has failed.

Jackson and Leelat (2017) show that representative agents do not exist for most commonly used demand functions. As a consequence, welfare implications based on representative agent models need not hold for individuals in an economy.[10]

This further implies that current macroeconomic models based on representative agents are not factually micro-founded. Much of the contemporary macroeconomic research, therefore, is not based on simple representative agents, but they often allow for rich heterogeneity of agents' behavior.

See also

References

- Robert J. Barro (1993), Macroeconomics, 4th ed. ISBN 0-471-57543-7.

- Maarten Janssen (2008), 'Microfoundations', in The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2nd ed.

- • E. Roy Weintraub (1977). "The Microfoundations of Macroeconomics: A Critical Survey," Journal of Economic Literature, 15(1), pp. 1-23.

• _____ (1979). Microfoundations: The Compatibility of Microeconomics and Macroeconomics, Cambridge. Description and preview. - • Thomas Cooley, ed., (1995), Frontiers of Business Cycle Research, Princeton University Press. Description and preview. ISBN 0-691-04323-X.

• Michael Woodford (2003), Interest and Prices: Foundations of a Theory of Monetary Policy, Princeton University Press. Description and Table of Contents. ISBN 0-691-01049-8. - Locatelli, Giorgio; Greco, Marco; Invernizzi, Diletta Colette; Grimaldi, Michele; Malizia, Stefania (2020-07-11). "What about the people? Micro-foundations of open innovation in megaprojects". International Journal of Project Management. doi:10.1016/j.ijproman.2020.06.009. ISSN 0263-7863.

- Angus Deaton (1992), Understanding Consumption, Oxford University Press. Description and chapter-preview links. ISBN 0-19-828824-7.

- 'The Smets-Wouters model': ECB webpage with discussion of advantages of microfounded macroeconomic models Archived 2009-02-26 at the Wayback Machine

- Kirman, Alan P (1992). "Whom or What Does the Representative Individual Represent?". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 6 (2): 117–136. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.401.3947. doi:10.1257/jep.6.2.117. ISSN 0895-3309.

- Rizvi, S. Abu Turab (1994), "The Microfoundations Project in General Equilibrium Theory", Cambridge Journal of Economics, 18 (4): 357–377, doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.cje.a035280

- Jackson, Matthew O.; Yariv, Leeat (2015). "The Non-Existence of Representative Agents". SSRN Working Paper Series. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2684776. ISSN 1556-5068.