The Anarchy

The Anarchy was a civil war in England and Normandy between 1135 and 1153, which resulted in a widespread breakdown in law and order. The conflict was a succession crisis precipitated by the accidental death by drowning of William Adelin, the only legitimate son of Henry I, in the sinking of the White Ship in 1120. Henry's attempts to install his daughter, the Empress Matilda, as his successor were unsuccessful and on Henry's death in 1135, his nephew Stephen of Blois seized the throne with the help of Stephen's brother, Henry of Blois, the Bishop of Winchester. Stephen's early reign was marked by fierce fighting with English barons, rebellious Welsh leaders and Scottish invaders. Following a major rebellion in the south-west of England, Matilda invaded in 1139 with the help of her half-brother Robert of Gloucester.

| The Anarchy | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

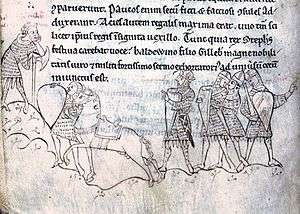

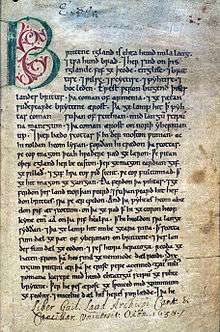

Near contemporary illustration of the Battle of Lincoln; Stephen (fourth from the right) listens to Baldwin of Clare orating a battle speech (left) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Forces loyal to Stephen of Blois | Forces loyal to Empress Matilda & Henry Plantagenet | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Stephen of Blois Matilda of Boulogne |

Empress Matilda Robert of Gloucester Geoffrey Plantagenet Henry Plantagenet | ||||||

Neither side was able to achieve a decisive advantage during the first years of the war; the Empress came to control the south-west of England and much of the Thames Valley, while Stephen remained in control of the south-east. The castles of the period were easily defensible, and so the fighting was mostly attrition warfare, comprising sieges, raiding and skirmishing between armies of knights and footsoldiers, many of them mercenaries. In 1141 Stephen was captured following the Battle of Lincoln, causing a collapse in his authority over most of the country. On the verge of being crowned queen, Empress Matilda was forced to retreat from London by hostile crowds; shortly afterwards, Robert of Gloucester was captured at the rout of Winchester and the two sides agreed to swap their respective captives. Stephen then almost seized Matilda in 1142 during the Siege of Oxford, but the Empress escaped from Oxford Castle across the frozen River Thames to safety.

The war dragged on for many more years. Empress Matilda's husband, Geoffrey V of Anjou, conquered Normandy, but in England neither side could achieve victory. Rebel barons began to acquire ever greater power in northern England and in East Anglia, with widespread devastation in the regions of major fighting. In 1148 the Empress returned to Normandy, leaving the campaigning in England to her young son Henry FitzEmpress. In 1152 Stephen and Matilda of Boulogne, queen consort and Stephen's wife, unsuccessfully attempted to have their eldest son, Eustace, recognised by the Catholic Church as the next king of England. By the early 1150s the barons and the Church mostly wanted a long-term peace.

When Henry FitzEmpress re-invaded England in 1153, neither faction's forces were keen to fight. After limited campaigning and the siege of Wallingford, Stephen and Henry agreed a negotiated peace, the Treaty of Wallingford, in which Stephen recognised Henry as his heir. Stephen died the next year and Henry ascended the throne as Henry II, the first Angevin king of England, beginning a long period of reconstruction. Chroniclers described the period as one in which "Christ and his saints were asleep" and Victorian historians called the conflict "the Anarchy" because of the chaos, although modern historians have questioned the accuracy of the term and of some contemporary accounts.[1]

Origins of the conflict

White Ship

The origins of the Anarchy lay in a succession crisis involving England and Normandy. In the 11th and 12th centuries, north-west France was controlled by a number of dukes and counts, frequently in conflict with one another for valuable territory.[2] In 1066 one of these men, Duke William II of Normandy, mounted an invasion to conquer the rich Anglo-Saxon kingdom of England, pushing on into south Wales and northern England in the ensuing years. The division and control of these lands after William's death proved problematic and his children fought multiple wars over the spoils.[3] William's son Henry I seized power after the death of his elder brother William Rufus and subsequently invaded and captured the Duchy of Normandy, controlled by his eldest brother Robert Curthose, defeating Robert's army at the Battle of Tinchebray.[4] Henry intended for his lands to be inherited by his only legitimate son, seventeen-year-old William Adelin.[5]

In 1120, the political landscape changed dramatically when the White Ship sank en route from Barfleur in Normandy to England; around three hundred passengers died, including Adelin.[6][nb 1] With Adelin dead, the inheritance to the English throne was thrown into doubt. Rules of succession in western Europe at the time were uncertain; in some parts of France, male primogeniture, in which the eldest son would inherit all titles, was becoming more popular.[8] In other parts of Europe, including Normandy and England, the tradition was for lands to be divided up, with the eldest son taking patrimonial lands – usually considered to be the most valuable – and younger sons being given smaller, or more recently acquired, partitions or estates.[8] The problem was further complicated by the sequence of unstable Anglo-Norman successions over the previous sixty years: there had been no peaceful, uncontested successions.[9]

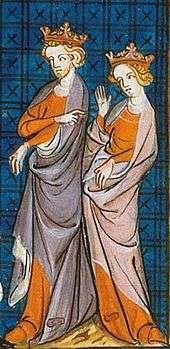

With William Adelin dead, Henry had only one other legitimate child, Matilda, but female rights of inheritance were unclear during this period.[10] Despite Henry taking a second wife, Adeliza of Louvain, it became increasingly unlikely that Henry would have another legitimate son and instead he looked to Matilda as his intended heir.[11] Matilda had been married to Henry V, Holy Roman Emperor, from which she later claimed the title of empress. Her husband died in 1125 and she was remarried in 1128 to Geoffrey V of Anjou, whose county bordered the Duchy of Normandy.[12] Geoffrey was unpopular with the Anglo-Norman elite: as an Angevin ruler, he was a traditional enemy of the Normans.[13] At the same time, tensions continued to grow as a result of Henry's domestic policies, in particular the high level of revenue he was raising to pay for his various wars.[14] Conflict was curtailed by the power of the king's personality and reputation.[15]

Henry attempted to build up a base of political support for Matilda in both England and Normandy, demanding that his court take oaths first in 1127, and then again in 1128 and 1131, to recognise Matilda as his immediate successor and recognise her descendants as the rightful ruler after her.[16] Stephen was amongst those who took this oath in 1127.[17] Nonetheless, relations between Henry, Matilda and Geoffrey became increasingly strained towards the end of the king's life. Matilda and Geoffrey suspected that they lacked genuine support in England, and proposed to Henry in 1135 that the king should hand over the royal castles in Normandy to Matilda whilst he was still alive and insist on the Norman nobility swearing immediate allegiance to her, thereby giving the couple a much more powerful position after Henry's death.[18] Henry angrily declined to do so, probably out of a concern that Geoffrey would try to seize power in Normandy somewhat earlier than intended.[19] A fresh rebellion broke out in southern Normandy, and Geoffrey and Matilda intervened militarily on behalf of the rebels.[8] In the middle of this confrontation, Henry unexpectedly fell ill and died near Lyons-la-Foret.[13]

Succession

After Henry's death, the English throne was taken not by his daughter Matilda, but by Stephen of Blois, ultimately resulting in civil war. Stephen was the son of Stephen-Henry of Blois, one of the powerful counts of northern France, and Adela of Normandy, daughter of William the Conqueror. Stephen and Matilda were thus first cousins. His parents allied themselves with Henry, and Stephen, as a younger son without lands of his own, became Henry's client, travelling as part of his court and serving in his campaigns.[20] In return he received lands and was married to Matilda of Boulogne in 1125, the daughter and only heiress of the Count of Boulogne, who owned the important continental port of Boulogne and vast estates in the north-west and south-east of England.[21] By 1135, Stephen was a well established figure in Anglo-Norman society, while his younger brother Henry had also risen to prominence, becoming the Bishop of Winchester and the second-richest man in England after the king.[22] Henry of Winchester was keen to reverse what he perceived as encroachment by the Norman kings on the rights of the church.[23]

When news began to spread of Henry I's death, many of the potential claimants to the throne were not well placed to respond. Geoffrey and Matilda were in Anjou, rather awkwardly supporting the rebels in their campaign against the royal army, which included a number of Matilda's supporters such as Robert of Gloucester.[8] Many of these barons had taken an oath to stay in Normandy until the late king was properly buried, which prevented them from returning to England.[24] Nonetheless, Geoffrey and Matilda took the opportunity to march into southern Normandy and seize a number of key castles; there they stopped, unable to advance further.[25] Stephen's elder brother Theobald, who had succeeded his father as count, was further south still, in Blois.[26]

Stephen was conveniently placed in Boulogne, and when news reached him of Henry's death he left for England, accompanied by his military household. Robert of Gloucester had garrisoned the ports of Dover and Canterbury and some accounts suggest that they refused Stephen access when he first arrived.[27] Nonetheless Stephen probably reached his own estate on the edge of London by 8 December and over the next week he began to seize power in England.[28]

The crowds in London traditionally claimed a right to elect the king of England, and they proclaimed Stephen the new monarch, believing that he would grant the city new rights and privileges in return.[29] Henry of Blois delivered the support of the church to Stephen: Stephen was able to advance to Winchester, where Roger, who was both the Bishop of Salisbury and the Lord Chancellor, instructed the royal treasury to be handed over to Stephen.[30] On 15 December, Henry delivered an agreement under which Stephen would grant extensive freedoms and liberties to the church, in exchange for the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Papal Legate supporting his succession to the throne.[31] There was the slight problem of the religious oath that Stephen had taken to support the Empress Matilda, but Henry convincingly argued that the late king had been wrong to insist that his court take the oath.[32] Furthermore, the late king had only insisted on that oath to protect the stability of the kingdom, and in light of the chaos that might now ensue, Stephen would be justified in ignoring it.[32] Henry was also able to persuade Hugh Bigod, the late king's royal steward, to swear that the king had changed his mind about the succession on his deathbed, nominating Stephen instead.[32][nb 2] Stephen's coronation was held a week later at Westminster Abbey on 26 December.[34][nb 3]

Meanwhile, the Norman nobility gathered at Le Neubourg to discuss declaring Theobald king, probably following the news that Stephen was gathering support in England.[36] The Normans argued that the count, as the more senior grandson of William the Conqueror, had the most valid claim over the kingdom and the duchy, and was certainly preferable to Matilda.[26] Theobald met with the Norman barons and Robert of Gloucester at Lisieux on 21 December but their discussions were interrupted by the sudden news from England that Stephen's coronation was to occur the next day.[37] Theobald then agreed to the Normans' proposal that he be made king, only to find that his former support immediately ebbed away: the barons were not prepared to support the division of England and Normandy by opposing Stephen.[38] Stephen subsequently financially compensated Theobald, who in return remained in Blois and supported his brother's succession.[39][nb 4]

Road to war

New regime (1135–38)

Stephen had to intervene in the north of England immediately after his coronation.[33] David I of Scotland, brother of Henry I's first queen and maternal uncle of Matilda, invaded the north on the news of Henry's death, taking Carlisle, Newcastle and other key strongholds.[33] Northern England was a disputed territory at this time, with the Scottish kings laying a traditional claim to Cumberland, and David also claiming Northumbria by virtue of his marriage to the daughter of the former Anglo-Saxon earl Waltheof.[41] Stephen rapidly marched north with an army and met David at Durham.[42] An agreement was made under which David would return most of the territory he had taken, with the exception of Carlisle. In return, Stephen confirmed David's son Prince Henry's possessions in England, including the Earldom of Huntingdon.[42]

Returning south, Stephen held his first royal court at Easter 1136.[43] A wide range of nobles gathered at Westminster for the event, including many of the Anglo-Norman barons and most of the higher officials of the church.[44] Stephen issued a new royal charter, confirming the promises he had made to the church, promising to reverse Henry's policies on the royal forests and to reform any abuses of the royal legal system.[45] Stephen portrayed himself as the natural successor to Henry I's policies, and reconfirmed the existing seven earldoms in the kingdom on their existing holders.[46] The Easter court was a lavish event, and a large amount of money was spent on the event itself, clothes and gifts.[47] Stephen gave out grants of land and favours to those present, and endowed numerous church foundations with land and privileges.[48] Stephen's accession to the throne still needed to be ratified by the Pope, and Henry of Blois appears to have been responsible for ensuring that testimonials of support were sent from Stephen's elder brother Theobald and from the French king Louis VI, to whom Stephen represented a useful balance to Angevin power in the north of France.[49] Pope Innocent II confirmed Stephen as king by letter later that year, and Stephen's advisers circulated copies widely around England to demonstrate Stephen's legitimacy.[50]

Troubles continued across Stephen's new kingdom. After the Welsh victory at the Battle of Llwchwr in January 1136 and the successful ambush of Richard Fitz Gilbert de Clare in April, south Wales rose in rebellion, starting in east Glamorgan and rapidly spreading across the rest of south Wales during 1137.[51] Owain Gwynedd and Gruffydd ap Rhys captured considerable territories, including Carmarthen Castle.[41] Stephen responded by sending Richard's brother Baldwin and the Marcher Lord Robert Fitz Harold of Ewyas into Wales to pacify the region. Neither mission was particularly successful and by the end of 1137 the king appears to have abandoned attempts to put down the rebellion. Historian David Crouch suggests that Stephen effectively "bowed out of Wales" around this time to concentrate on his other problems.[52] Meanwhile, Stephen had put down two revolts in the south-west led by Baldwin de Redvers and Robert of Bampton; Baldwin was released after his capture and travelled to Normandy, where he became an increasingly vocal critic of the king.[53]

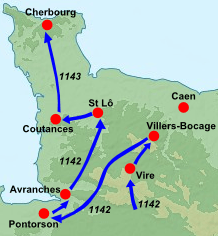

Geoffrey of Anjou attacked Normandy in early 1136 and, after a temporary truce, invaded later the same year, raiding and burning estates rather than trying to hold the territory.[54] Events in England meant that Stephen was unable to travel to Normandy himself, so Waleran de Beaumont, appointed by Stephen as the lieutenant of Normandy, and Theobald led the efforts to defend the duchy.[55] Stephen himself only returned to the duchy in 1137, where he met with Louis VI and Theobald to agree to an informal regional alliance, probably brokered by Henry, to counter the growing Angevin power in the region.[56] As part of this deal, Louis recognised Stephen's son Eustace as Duke of Normandy in exchange for Eustace giving fealty to the French king.[57] Stephen was less successful in regaining the Argentan province along the Normandy and Anjou border, which Geoffrey had taken at the end of 1135.[58] Stephen formed an army to retake it, but the frictions between his Flemish mercenary forces led by William of Ypres and the local Norman barons resulted in a battle between the two halves of his army.[59] The Norman forces then deserted the king, forcing Stephen to give up his campaign.[60] Stephen agreed to another truce with Geoffrey, promising to pay him 2,000 marks a year in exchange for peace along the Norman borders.[54][nb 5]

Stephen's first years as king can be interpreted in different ways. Seen positively, Stephen stabilised the northern border with Scotland, contained Geoffrey's attacks on Normandy, was at peace with Louis VI, enjoyed good relations with the church and had the broad support of his barons.[63] There were significant underlying problems, nonetheless. The north of England was now controlled by David and Prince Henry, Stephen had abandoned Wales, the fighting in Normandy had considerably destabilised the duchy, and an increasing number of barons felt that Stephen had given them neither the lands nor the titles they felt they deserved or were owed.[64] Stephen was also rapidly running out of money: Henry's considerable treasury had been emptied by 1138 due to the costs of running Stephen's more lavish court, and the need to raise and maintain his mercenary armies fighting in England and Normandy.[65]

Early fighting (1138–39)

Fighting broke out on several fronts during 1138. Firstly, Robert of Gloucester rebelled against the king, starting the descent into civil war in England.[65] An illegitimate son of Henry I and the half-brother of the Empress Matilda, Robert was one of the most powerful Anglo-Norman barons, controlling estates in Normandy as well as the Earldom of Gloucester.[66] In 1138, Robert renounced his fealty to Stephen and declared his support for Matilda, triggering a major regional rebellion in Kent and across the south-west of England, although Robert himself remained in Normandy.[67] Matilda had not been particularly active in asserting her claims to throne since 1135 and in many ways it was Robert that took the initiative in declaring war in 1138.[68] In France, Geoffrey took advantage of the situation by re-invading Normandy. David of Scotland also invaded the north of England once again, announcing that he was supporting the claim of his niece the Empress Matilda to the throne, pushing south into Yorkshire.[69][nb 6]

Stephen rapidly responded to the revolts and invasions, focusing primarily on England rather than Normandy. His wife Matilda was sent to Kent with ships and resources from Boulogne, with the task of retaking the key port of Dover, under Robert's control.[66] A small number of Stephen's household knights were sent north to help the fight against the Scots, where David's forces were defeated later that year at the Battle of the Standard in August by the forces of Thurstan, the Archbishop of York.[69] Despite this victory, David still occupied most of the north of England.[69] Stephen himself went west in an attempt to regain control of Gloucestershire, first striking north into the Welsh Marches, taking Hereford and Shrewsbury, then heading south to Bath.[66] Bristol proved too strong for him, and Stephen contented himself with raiding and pillaging the surrounding area.[66] The rebels appear to have expected Robert to intervene with support, but he remained in Normandy throughout the year, trying to persuade the Empress Matilda to invade England herself.[70] Dover finally surrendered to the queen's forces later in the year.[71]

Stephen's military campaign in England had progressed well, and historian David Crouch describes it as "a military achievement of the first rank".[71] The king took the opportunity of his military advantage to forge a peace agreement with Scotland.[71] Stephen's wife Matilda was sent to negotiate another agreement between Stephen and David, called the treaty of Durham; Northumbria and Cumbria would effectively be granted to David and his son Henry, in exchange for their fealty and future peace along the border.[69] The powerful Ranulf, Earl of Chester, considered himself to hold the traditional rights to Carlisle and Cumberland and was extremely displeased to see them being given to the Scots, a problem which would have long lasting implications in the war.[72]

Preparations for war (1139)

By 1139, an invasion of England by Robert and Matilda appeared imminent. Geoffrey and Matilda had secured much of Normandy and, together with Robert, spent the beginning of the year mobilising forces ready for a cross-Channel expedition.[73] Matilda also appealed to the papacy at the start of the year, putting forward her legal claim to the English throne; unsurprisingly, the pope declined to reverse his earlier support for Stephen, but from Matilda's perspective the case usefully established that Stephen's claim was disputed.[74]

Meanwhile, Stephen prepared for the coming conflict by creating a number of additional earldoms.[75] Only a handful of earldoms had existed under Henry I and these had been largely symbolic in nature. Stephen created many more, filling them with men he considered to be loyal, capable military commanders, and in the more vulnerable parts of the country assigning them new lands and additional executive powers.[76][nb 7] Stephen appears to have had several objectives in mind, including both ensuring the loyalty of his key supporters by granting them these honours, and improving his defences in vulnerable parts of the kingdom. Stephen was heavily influenced by his principal advisor, Waleran de Beaumont, the twin brother of Robert of Leicester. The Beaumont twins and their younger brother and cousins received the majority of these new earldoms.[78] From 1138 onwards, Stephen gave them the earldoms of Worcester, Leicester, Hereford, Warwick and Pembroke, which—especially when combined with the possessions of Stephen's new ally, Prince Henry, in Cumberland and Northumbria—created a wide block of territory to act as a buffer zone between the troubled south-west, Chester and the rest of the kingdom.[79]

Stephen took steps to remove a group of bishops he regarded as a threat to his rule. The royal administration under Henry I had been headed by Roger, the Bishop of Salisbury, supported by Roger's nephews, Alexander and Nigel, the Bishops of Lincoln and Ely respectively, and Roger's son, Roger le Poer, who was the Lord Chancellor.[80] These bishops were powerful landowners as well as ecclesiastical rulers, and they had begun to build new castles and increase the size of their military forces, leading Stephen to suspect that they were about to defect to the Empress Matilda. Roger and his family were also enemies of Waleran, who disliked their control of the royal administration.[81] In June 1139, Stephen held his court in Oxford, where a fight between Alan of Brittany and Roger's men broke out, an incident probably deliberately created by Stephen.[81] Stephen responded by demanding that Roger and the other bishops surrender all of their castles in England. This threat was backed up by the arrest of the bishops, with the exception of Nigel who had taken refuge in Devizes Castle; the bishop only surrendered after Stephen besieged the castle and threatened to execute Roger le Poer.[82] The remaining castles were then surrendered to the king.[81][nb 8] The incident removed any military threat from the bishops, but it may have damaged Stephen's relationship with the senior clergy, and in particular with his brother Henry.[84][nb 9] Both sides were now ready for war.

Warfare

Technology and tactics

Anglo-Norman warfare during the civil war was characterised by attritional military campaigns, in which commanders tried to raid enemy lands and seize castles in order to allow them to take control of their adversaries' territory, ultimately winning slow, strategic victories.[86] Occasionally pitched battles were fought between armies but these were considered highly risky endeavours and were usually avoided by prudent commanders.[86] Despite the use of feudal levies, Norman warfare traditionally depended on rulers raising and spending large sums of cash.[87] The cost of warfare had risen considerably in the first part of the 12th century, and adequate supplies of ready cash were increasingly proving important in the success of campaigns.[88]

Stephen and Matilda's households centred on small bodies of knights called the familia regis; this inner circle formed the basis for a headquarters in any military campaign.[89] The armies of the period were still similar to those of the previous century, comprising bodies of mounted, armoured knights, supported by infantry.[90] Many of these men would have worn long, ring armour tunics, with helmets, greaves and arm protection.[90] Swords were common, along with lances for cavalry; crossbowmen had become more numerous, and longbows were occasionally used in battle alongside the older shortbow.[90] These forces were either feudal levies, drawn up by local nobles for a limited period of service during a campaign or, increasingly, mercenaries, who were expensive but more flexible in the duration of their service and often more skilled.[91]

The Normans had first developed castles in the 10th and 11th centuries, and their occupation of England after 1066 had made extensive use of them. Most castles took the form of earthwork and timber motte-and-bailey or ringwork constructs; easily built with local labour and resources, these were resilient and easy to defend. The Anglo-Norman elite became adept at strategically placing these castles along rivers and valleys to control populations, trade and regions.[92] In the decades before the civil war, some newer, stone-built keeps had begun to be introduced. Unlike the more traditional designs, these required expensive skilled labourers and could only be built slowly over many seasons. Although these square keeps later proved to have vulnerabilities, the ballistae and mangonels used in the 1140s were significantly less powerful than the later trebuchet designs, giving defenders a substantial advantage over attackers.[93] As a result, slow sieges to starve defenders out, or mining operations to undermine walls, tended to be preferred by commanders over direct assaults.[86]

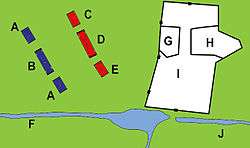

Both sides responded by building new castles, sometimes creating systems of strategic fortifications. In the south-west Matilda's supporters built a range of castles to protect the territory, usually motte-and-bailey designs such as those at Winchcombe, Upper Slaughter, or Bampton.[94] Similarly, Stephen built a new chain of fen-edge castles at Burwell, Lidgate, Rampton, Caxton, and Swavesey – each about six to nine miles (ten to fifteen km) apart – in order to protect his lands around Cambridge.[95] Many of these castles were termed "adulterine", unauthorised, because, in the chaos of the war, no royal permission had given to the lord for their construction.[96] Contemporary chroniclers saw this as a matter of concern; Robert of Torigni suggested that as many as 1,115 such castles had been built during the conflict, although this was probably an exaggeration as elsewhere he suggests an alternative figure of 126.[97]

Another feature of the war was the creation of many "counter-castles".[98] or "siege castles". At least 17 such sites have been identified through documentary and archaeological research, but this likely under-estimates the number that were built during the conflict.[99] These had been used in English conflicts for several years before the civil war and involved building a basic castle during a siege, alongside the main target of attack.[100] Typically these would be built in either a ringwork or a motte-and-bailey design between 200 and 300 yards (180 to 270 metres) away from the target, just beyond the range of a bow.[100] Counter-castles could be used to either act as platforms for siege weaponry, or as bases for controlling the region in their own right.[101] Most siege castles were intended for temporary use and were often destroyed (slighted) afterwards. While most survive poorly, the earthworks of 'the Rings' near Corfe in Dorset is an unusually well preserved example.[102]

Leaders

King Stephen was extremely wealthy, well-mannered, modest and liked by his peers; he was also considered a man capable of firm action.[103] His personal qualities as a military leader focused on his skill in personal combat, his capabilities in siege warfare and a remarkable ability to move military forces quickly over relatively long distances.[104] Rumours of his father's cowardice during the First Crusade continued to circulate, and a desire to avoid the same reputation may have influenced some of Stephen's rasher military actions.[105] Stephen drew heavily on his wife, Queen Matilda of Boulogne (not to be confused with Empress Matilda), during the conflict, both for leading negotiations and maintaining his cause and army while imprisoned in 1141; Matilda led the royal household during this period in partnership with Stephen's mercenary leader William of Ypres.[106]

The Empress's faction lacked an equivalent war leader to Stephen. Matilda had a firm grounding in government from her time as empress, where she had presided in court cases and acted as regent in Italy with the Imperial army on campaign.[107] Nonetheless, Matilda, as a woman, could not personally lead forces into battle.[108] Matilda was less popular with contemporary chroniclers than Stephen; in many ways she took after her father, being prepared to loudly demand compliance of her court, when necessary issuing threats and generally appearing arrogant.[109] This was felt to be particularly inappropriate since she was a woman.[110] Matilda's husband, Geoffrey of Anjou, played an important role in seizing Normandy during the war but did not cross into England. Geoffrey and Matilda's marriage was not an easy one; it had almost collapsed altogether in 1130.[111]

For most of the war, therefore, the Angevin armies were led into battle by a handful of senior nobles. The most important of these was Robert of Gloucester, the half-brother of the Empress. He was known for his qualities as a statesman, his military experience and leadership ability.[66] Robert had tried to convince Theobald to take the throne in 1135; he did not attend Stephen's first court in 1136 and it took several summonses to convince him to attend court at Oxford later that year.[112] Miles of Gloucester was another capable military leader up until his death in 1143; there were some political tensions between him and Robert, but the two could work together on campaigns.[113] One of Matilda's most loyal followers was Brian Fitz Count, like Miles a marcher lord from Wales. Fitz Count was apparently motivated by a strong moral duty to uphold his oath to Matilda and proved critical in defending the Thames corridor.[114]

Civil war

Initial phase of the war (1139–40)

The Angevin invasion finally arrived in August. Baldwin de Redvers crossed over from Normandy to Wareham in an initial attempt to capture a port to receive the Empress Matilda's invading army, but Stephen's forces forced him to retreat into the south-west.[115] The following month the Empress was invited by the Dowager Queen Adeliza to land at Arundel instead, and on 30 September Robert of Gloucester and the Empress arrived in England with 140 knights.[115][nb 10] Matilda stayed at Arundel Castle, whilst Robert marched north-west to Wallingford and Bristol, hoping to raise support for the rebellion and to link up with Miles of Gloucester, who took the opportunity to renounce his fealty to the king.[117]

Stephen responded by promptly moving south, besieging Arundel and trapping Matilda inside the castle.[118] Stephen then agreed to a truce proposed by his brother, Henry of Blois; the full details of the truce are not known, but the results were that Stephen first released Matilda from the siege and then allowed her and her household of knights to be escorted to the south-west, where they were reunited with Robert of Gloucester.[118] The reasoning behind Stephen's decision to release his rival remains unclear. Contemporary chroniclers suggested that Henry argued that it would be in Stephen's own best interests to release the Empress and concentrate instead on attacking Robert, and Stephen may have seen Robert, not the Empress, as his main opponent at this point in the conflict.[118] Stephen also faced a military dilemma at Arundel—the castle was considered almost impregnable, and he may have been worried that he was tying down his army in the south whilst Robert roamed freely in the west.[119] Another theory is that Stephen released Matilda out of a sense of chivalry; Stephen was certainly known for having a generous, courteous personality and women were not normally expected to be targeted in Anglo-Norman warfare.[120][nb 11]

Although there had been few new defections to the Empress, Matilda now controlled a compact block of territory stretching out from Gloucester and Bristol south-west into Devon and Cornwall, west into the Welsh Marches and east as far as Oxford and Wallingford, threatening London.[122] She had established her court in Gloucester, close to Robert's stronghold of Bristol but far enough away for her to remain independent of her half-brother.[123] Stephen set about reclaiming the region.[124] He started by attacking Wallingford Castle which controlled the Thames corridor; it was held by Brien FitzCount and Stephen found it too well defended.[125] Stephen left behind some forces to blockade the castle and continued west into Wiltshire to attack Trowbridge, taking the castles of South Cerney and Malmesbury en route.[126] Meanwhile, Miles of Gloucester marched east, attacking Stephen's rearguard forces at Wallingford and threatening an advance on London.[127] Stephen was forced to give up his western campaign, returning east to stabilise the situation and protect his capital.[128]

At the start of 1140, Nigel, the Bishop of Ely, whose castles Stephen had confiscated the previous year, rebelled against Stephen as well.[128] Nigel hoped to seize East Anglia and established his base of operations in the Isle of Ely, then surrounded by protective fenland.[128] Stephen responded quickly, taking an army into the fens and using boats lashed together to form a causeway that allowed him to make a surprise attack on the isle.[129] Nigel escaped to Gloucester, but his men and castle were captured, and order was temporarily restored in the east.[129] Robert of Gloucester's men retook some of the territory that Stephen had taken in his 1139 campaign.[130] In an effort to negotiate a truce, Henry of Blois held a peace conference at Bath, at which Robert represented the Empress, and Queen Matilda and Archbishop Theobald the King.[131] The conference collapsed over the insistence by Henry and the clergy that they should set the terms of any peace deal, which Stephen found unacceptable.[132]

Ranulf of Chester remained upset over Stephen's gift of the north of England to Prince Henry.[72] Ranulf devised a plan for dealing with the problem by ambushing Henry whilst the prince was travelling back from Stephen's court to Scotland after Christmas.[72] Stephen responded to rumours of this plan by escorting Henry himself north, but this gesture proved the final straw for Ranulf.[72] Ranulf had previously claimed that he had the rights to Lincoln Castle, held by Stephen, and under the guise of a social visit, Ranulf seized the fortification in a surprise attack.[133] Stephen marched north to Lincoln and agreed to a truce with Ranulf, probably to keep him from joining the Empress's faction, under which Ranulf would be allowed to keep the castle.[134] Stephen returned to London but received news that Ranulf, his brother and their family were relaxing in Lincoln Castle with a minimal guard force, a ripe target for a surprise attack of his own.[134] Abandoning the deal he had just made, Stephen gathered his army again and sped north, but not quite fast enough—Ranulf escaped Lincoln and declared his support for the Empress, and Stephen was forced to place the castle under siege.[134]

Second phase of the war (1141–42)

Battle of Lincoln

While Stephen and his army besieged Lincoln Castle at the start of 1141, Robert of Gloucester and Ranulf of Chester advanced on the king's position with a somewhat larger force.[135] When the news reached Stephen, he held a council to decide whether to give battle or to withdraw and gather additional soldiers: Stephen decided to fight, resulting in the Battle of Lincoln on 2 February 1141.[135] The king commanded the centre of his army, with Alan of Brittany on his right and William of Aumale on his left.[136] Robert and Ranulf's forces had superiority in cavalry and Stephen dismounted many of his own knights to form a solid infantry block; he joined them himself, fighting on foot in the battle.[136][nb 12] Stephen was not a gifted public speaker, and delegated the pre-battle speech to Baldwin of Clare, who delivered a rousing declaration.[138] After an initial success in which William's forces destroyed the Angevins' Welsh infantry, the battle went badly for Stephen.[139] Robert and Ranulf's cavalry encircled Stephen's centre, and the king found himself surrounded by the enemy army.[139] Many of Stephen's supporters, including Waleron de Beaumont and William of Ypres, fled from the field at this point but Stephen fought on, defending himself first with his sword and then, when that broke, with a borrowed battle axe.[140] Finally, he was overwhelmed by Robert's men and taken away from the field in custody.[140][nb 13]

Robert took Stephen back to Gloucester, where the king met with the Empress Matilda, and was then moved to Bristol Castle, traditionally used for holding high-status prisoners.[142] He was initially left confined in relatively good conditions, but his security was later tightened and he was kept in chains.[142] The Empress now began to take the necessary steps to have herself crowned queen in his place, which would require the agreement of the church and her coronation at Westminster.[143] Stephen's brother Henry summoned a council at Winchester before Easter in his capacity as papal legate to consider the clergy's view. He had made a private deal with the Empress Matilda that he would deliver the support of the church, if she agreed to give him control over church business in England.[144] Henry handed over the royal treasury, rather depleted except for Stephen's crown, to the Empress, and excommunicated many of Stephen's supporters who refused to switch sides.[145] Archbishop Theobald of Canterbury was unwilling to declare Matilda queen so rapidly, and a delegation of clergy and nobles, headed by Theobald, travelled to see Stephen in Bristol and consult about their moral dilemma: should they abandon their oaths of fealty to the king?[144] Stephen agreed that, given the situation, he was prepared to release his subjects from their oath of fealty to him.[146]

The clergy gathered again in Winchester after Easter to declare the Empress "Lady of England and Normandy" as a precursor to her coronation.[146] While Matilda's own followers attended the event, few other major nobles seem to have attended and a delegation from London prevaricated.[147] Queen Matilda wrote to complain and demand Stephen's release.[148] The Empress Matilda then advanced to London to stage her coronation in June, where her position became precarious.[149] Despite securing the support of Geoffrey de Mandeville, who controlled the Tower of London, forces loyal to Stephen and Queen Matilda remained close to the city and the citizens were fearful about welcoming the Empress.[150] On 24 June, shortly before the planned coronation, the city rose up against the Empress and Geoffrey de Mandeville; Matilda and her followers only just fled in time, making a chaotic retreat to Oxford.[151]

Meanwhile, Geoffrey of Anjou invaded Normandy again and, in the absence of Waleran of Beaumont, who was still fighting in England, Geoffrey took all the duchy south of the River Seine and east of the Risle.[152] No help was forthcoming from Stephen's brother Theobald this time either, who appears to have been preoccupied with his own problems with France—the new French king, Louis VII, had rejected his father's regional alliance, improving relations with Anjou and taking a more bellicose line with Theobald, which would result in war the following year.[153] Geoffrey's success in Normandy and Stephen's weakness in England began to influence the loyalty of many Anglo-Norman barons, who feared losing their lands in England to Robert and the Empress, and their possessions in Normandy to Geoffrey.[154] Many started to leave Stephen's faction. His friend and advisor Waleron was one of those who decided to defect in mid-1141, crossing into Normandy to secure his ancestral possessions by allying himself with the Angevins, and bringing Worcestershire into the Empress's camp.[155] Waleron's twin brother, Robert of Leicester, effectively withdrew from fighting in the conflict at the same time. Other supporters of the Empress were restored in their former strongholds, such as Bishop Nigel of Ely, and others still received new earldoms in the west of England. The royal control over the minting of coins broke down, leading to coins being struck by local barons and bishops across the country.[156]

Rout of Winchester and the siege of Oxford

Stephen's wife Matilda played a critical part in keeping the king's cause alive during his captivity. Queen Matilda gathered Stephen's remaining lieutenants around her and the royal family in the south-east, advancing into London when the population rejected the Empress.[157] Stephen's long-standing commander William of Ypres remained with the queen in London; William Martel, the royal steward, commanded operations from Sherborne in Dorset, and Faramus of Boulogne ran the royal household.[158] The queen appears to have generated genuine sympathy and support from Stephen's more loyal followers.[157] Henry's alliance with the Empress proved short-lived, as they soon fell out over political patronage and ecclesiastical policy; the bishop met Stephen's wife Queen Matilda at Guildford and transferred his support to her.[159]

The Empress's position was transformed by her defeat at the rout of Winchester. Following their retreat from London, Robert of Gloucester and the Empress besieged Henry in his episcopal castle at Winchester in July.[160] Matilda was using the royal castle in the city of Winchester as a base for her operations, but shortly afterwards Queen Matilda and William of Ypres then encircled the Angevin forces with their own army, reinforced with fresh troops from London.[161] The Empress Matilda decided to escape from the city with her close associates Fitz Count and Reginald of Cornwall, while the rest of her army delayed the royal forces.[162] In the subsequent battle the Empress's forces were defeated and Robert of Gloucester himself was taken prisoner during the retreat, although Matilda herself escaped, exhausted, to her fortress at Devizes.[163]

With both Stephen and Robert held prisoner, negotiations were held to try to agree a long term peace settlement, but Queen Matilda was unwilling to offer any compromise to the Empress, and Robert refused to accept any offer to encourage him to change sides to Stephen.[164] Instead, in November the two sides simply exchanged the two leaders, Stephen returning to his queen, and Robert to the Empress in Oxford.[165] Henry held another church council, which reversed its previous decision and reaffirmed Stephen's legitimacy to rule, and a fresh coronation of Stephen and Matilda occurred at Christmas 1141.[164] At the beginning of 1142 Stephen fell ill, and by Easter rumours had begun to circulate that he had died.[166] Possibly this illness was the result of his imprisonment the previous year, but he finally recovered and travelled north to raise new forces and to successfully convince Ranulf of Chester to change sides once again.[167] Stephen then spent the summer attacking some of the new Angevin castles built the previous year, including Cirencester, Bampton and Wareham.[168]

During mid-1142 Robert returned to Normandy to assist Geoffrey with operations against some of Stephen's remaining followers there; he returned to England later in the year.[169] Meanwhile, Matilda came under increased pressure from Stephen's forces and had become surrounded at Oxford.[168] Oxford was a secure town, protected by walls and the River Isis, but Stephen led a sudden attack across the river, leading the charge and swimming part of the way.[170] Once on the other side, the king and his men broke into the town, trapping the Empress in the castle.[170] Oxford Castle was a powerful fortress and, rather than storming it, Stephen had to settle down for a long siege, secure in the knowledge that Matilda was now surrounded.[170] Just before Christmas, the Empress sneaked out of the castle, crossed the icy river on foot and made her escape past the royal army to safety at Wallingford, leaving the castle garrison free to surrender the next day. Matilda stayed with Fitz Count for a period, then reestablished her court at Devizes.[171]

Stalemate (1143–46)

The war between the two sides in England reached a stalemate in the mid-1140s, while Geoffrey of Anjou consolidated his hold on power in Normandy, being recognised as duke of Normandy after taking Rouen in 1144.[172] 1143 started precariously for Stephen when he was besieged by Robert of Gloucester at Wilton Castle, an assembly point for royal forces in Herefordshire.[173] Stephen attempted to break out and escape, resulting in the Battle of Wilton. Once again, the Angevin cavalry proved too strong, and for a moment it appeared that Stephen might be captured for a second time.[174] On this occasion William Martel, Stephen's steward, made a fierce rear guard effort, allowing Stephen to escape from the battlefield.[173] Stephen valued William's loyalty sufficiently to agree to exchange Sherborne Castle for his safe release—this was one of the few instances where Stephen was prepared to give up a castle to ransom one of his men.[175]

In late 1143, Stephen faced a new threat in the east, when Geoffrey de Mandeville, the Earl of Essex, rose up in rebellion against the king in East Anglia.[176] Stephen had disliked the baron for several years, and provoked the conflict by summoning Geoffrey to court, where the king arrested him.[177] Stephen threatened to execute Geoffrey unless the baron handed over his various castles, including the Tower of London, Saffron Walden and Pleshey, all important fortifications because they were in, or close to, London.[177] Geoffrey gave in, but once free he headed north-east into the Fens to the Isle of Ely, from where he began a military campaign against Cambridge, with the intention of progressing south towards London.[178] With all of his other problems and with Hugh Bigod still in open revolt in Norfolk, Stephen lacked the resources to track Geoffrey down in the Fens and made do with building a screen of castles between Ely and London, including Burwell Castle.[179]

For a period, the situation continued to worsen. Ranulf of Chester revolted once again in the middle of 1144, splitting up Stephen's Honour of Lancaster between himself and Prince Henry.[180] In the west, Robert of Gloucester and his followers continued to raid the surrounding royalist territories, and Wallingford Castle remained a secure Angevin stronghold, too close to London for comfort.[180] Meanwhile, Geoffrey of Anjou finished securing his hold on southern Normandy and in January 1144 he advanced into Rouen, the capital of the duchy, concluding his campaign.[167] Louis VII recognised him as Duke of Normandy shortly after.[181] By this point in the war, Stephen was depending increasingly on his immediate royal household, such as William of Ypres and others, and lacked the support of the major barons who might have been able to provide him with significant additional forces; after the events of 1141, Stephen made little use of his network of earls.[182]

After 1143 the war ground on, but progressing slightly better for Stephen.[183] Miles of Gloucester, one of the most talented Angevin commanders, had died whilst hunting over the previous Christmas, relieving some of the pressure in the west.[184] Geoffrey de Mandeville's rebellion continued until September 1144, when he died during an attack on Burwell.[185] The war in the west progressed better in 1145, with the king recapturing Faringdon Castle in Oxfordshire.[185] In the north, Stephen came to a fresh agreement with Ranulf of Chester, but then in 1146 repeated the ruse he had played on Geoffrey de Mandeville in 1143, first inviting Ranulf to court, then arresting him and threatening to execute him unless he handed over several castles, including Lincoln and Coventry.[180] As with Geoffrey, the moment Ranulf was released he immediately rebelled, but the situation was a stalemate: Stephen had few forces in the north with which to prosecute a fresh campaign, whilst Ranulf lacked the castles to support an attack on Stephen.[180] By this point, Stephen's practice of inviting barons to court and arresting them had brought him into some disrepute and increasing distrust.[186]

Final phases of the war (1147–52)

The character of the conflict in England gradually began to shift; as historian Frank Barlow suggests, by the late 1140s "the civil war was over", barring the occasional outbreak of fighting.[187] In 1147 Robert of Gloucester died peacefully, and the next year the Empress Matilda defused an argument with the Church over the ownership of Devizes Castle by returning to Normandy, contributing to reducing the tempo of the war.[188] The Second Crusade was announced, and many Angevin supporters, including Waleran of Beaumont, joined it, leaving the region for several years.[187] Many of the barons were making individual peace agreements with each other to secure their lands and war gains.[189] Geoffrey and Matilda's son, the future King Henry II, mounted a small mercenary invasion of England in 1147 but the expedition failed, not least because Henry lacked the funds to pay his men.[187] Surprisingly, Stephen himself ended up paying their costs, allowing Henry to return home safely; his reasons for doing so are unclear. One potential explanation is his general courtesy to a member of his extended family; another is that he was starting to consider how to end the war peacefully, and saw this as a way of building a relationship with Henry.[190]

Many of the most powerful nobles began to make their own truces and disarmament agreements, signing treaties between one another that typically promised an end to bilateral hostilities, limited the building of new castles, or agreed limits to the size of armies sent against one another.[191] Typically these treaties included clauses that recognised that the nobles might, of course, be forced to fight each other by instruction of their rulers.[192] A network of treaties had emerged by the 1150s, reducing – but not eliminating – the degree of local fighting in England.[193]

Matilda remained in Normandy for the rest of the war, focusing on stabilising the duchy and promoting her son's rights to the English throne.[194] The young Henry FitzEmpress returned to England again in 1149, this time planning to form a northern alliance with Ranulf of Chester.[195] The Angevin plan involved Ranulf agreeing to give up his claim to Carlisle, held by the Scots, in return for being given the rights to the whole of the Honour of Lancaster; Ranulf would give homage to both David and Henry FitzEmpress, with Henry having seniority.[196] Following this peace agreement, Henry and Ranulf agreed to attack York, probably with help from the Scots.[197] Stephen marched rapidly north to York and the planned attack disintegrated, leaving Henry to return to Normandy, where he was declared Duke by his father.[198][nb 14] Although still young, Henry was increasingly gaining a reputation as an energetic and capable leader. His prestige and power increased further when he unexpectedly married Eleanor of Aquitaine in 1152; Eleanor was the attractive Duchess of Aquitaine and the recently divorced wife of Louis VII of France, and the marriage made Henry the future ruler of a huge swathe of territory across France.[199]

In the final years of the war, Stephen too began to focus on the issue of his family and the succession.[200] Stephen had given his eldest son Eustace the County of Boulogne in 1147, but it remained unclear whether Eustace would inherit England.[201] Stephen's preferred option was to have Eustace crowned while he himself was still alive, as was the custom in France, but this was not the normal practice in England, and Celestine II, during his brief tenure as pope between 1143 and 1144, had banned any change to this practice.[201] The only person who could crown Eustace was Archbishop Theobald, who may well have seen the coronation of Eustace only as a guarantee of further civil war after Stephen's death; the Archbishop refused to crown Eustace without agreement from the current pope, Eugene III, and the matter reached an impasse.[202] Stephen's situation was made worse by various arguments with members of the Church over rights and privileges.[203] Stephen made a fresh attempt to have Eustace crowned at Easter 1152, gathering his nobles to swear fealty to Eustace, and then insisting that Theobald and his bishops anoint him king.[204] When Theobald refused yet again, Stephen and Eustace imprisoned both him and the bishops and refused to release them unless they agreed to crown Eustace.[204] Theobald escaped again into temporary exile in Flanders, pursued to the coast by Stephen's knights, marking a low point in Stephen's relationship with the church.[204]

End of the war

Peace negotiations (1153–54)

Henry FitzEmpress returned to England again at the start of 1153 with a small army, supported in the north and east of England by Ranulf of Chester and Hugh Bigod.[205] Stephen's castle at Malmesbury was besieged by Henry's forces and the king responded by marching west with an army to relieve it.[206] Stephen unsuccessfully attempted to force Henry's smaller army to fight a decisive battle along the River Avon.[206] In the face of the increasingly wintry weather, Stephen agreed to a temporary truce and returned to London, leaving Henry to travel north through the Midlands where the powerful Robert de Beaumont, Earl of Leicester, announced his support for the Angevin cause.[206] Despite only modest military successes, Henry and his allies now controlled the south-west, the Midlands and much of the north of England.[207] A delegation of senior English clergy met with Henry and his advisers at Stockbridge shortly before Easter.[208] Many of the details of their discussions are unclear, but it appears that the churchmen emphasised that while they supported Stephen as king, they sought a negotiated peace; Henry reaffirmed that he would avoid the English cathedrals and would not expect the bishops to attend his court.[209]

Stephen intensified the long-running siege of Wallingford Castle in a final attempt to take this major Angevin stronghold.[210] The fall of Wallingford appeared imminent and Henry marched south in an attempt to relieve the siege, arriving with a small army and placing Stephen's besieging forces under siege themselves.[211] Upon news of this, Stephen gathered up a large force and marched from Oxford, and the two sides confronted each other across the River Thames at Wallingford in July.[211] By this point in the war, the barons on both sides seem to have been eager to avoid an open battle.[212] As a result, instead of a battle ensuing, members of the church brokered a truce, to the annoyance of both Stephen and Henry.[212]

In the aftermath of Wallingford, Stephen and Henry spoke together privately about a potential end to the war; Stephen's son Eustace was furious about the peaceful outcome at Wallingford. He left his father and returned home to Cambridge to gather more funds for a fresh campaign, where he fell ill and died the next month.[213] Eustace's death removed an obvious claimant to the throne and was politically convenient for those seeking a permanent peace in England. It is possible that Stephen had already begun to consider passing over Eustace's claim; historian Edmund King observes that Eustace's claim to the throne was not mentioned in the discussions at Wallingford, for example, and this may have added to Stephen's son's anger.[214]

Fighting continued after Wallingford, but in a rather half-hearted fashion. Stephen lost the towns of Oxford and Stamford to Henry while the king was diverted fighting Hugh Bigod in the east of England, but Nottingham Castle survived an Angevin attempt to capture it.[215] Meanwhile, Stephen's brother Henry of Blois and Archbishop Theobald of Canterbury were for once unified in an effort to broker a permanent peace between the two sides, putting pressure on Stephen to accept a deal.[216] Stephen and Henry FitzEmpress's armies met again at Winchester, where the two leaders would ratify the terms of a permanent peace in November.[217] Stephen announced the Treaty of Winchester in Winchester Cathedral: he recognised Henry FitzEmpress as his adopted son and successor, in return for Henry doing homage to him; Stephen promised to listen to Henry's advice, but retained all his royal powers; Stephen's remaining son, William, would do homage to Henry and renounce his claim to the throne, in exchange for promises of the security of his lands; key royal castles would be held on Henry's behalf by guarantors whilst Stephen would have access to Henry's castles; and the numerous foreign mercenaries would be demobilised and sent home.[218] Stephen and Henry sealed the treaty with a kiss of peace in the cathedral.[219]

Transition and reconstruction (1154–65)

Stephen's decision to recognise Henry as his heir was, at the time, not necessarily a final solution to the civil war.[220] Despite the issuing of new currency and administrative reforms, Stephen might potentially have lived for many more years, whilst Henry's position on the continent was far from secure.[220] Although Stephen's son William was young and unprepared to challenge Henry for the throne in 1153, the situation could well have shifted in subsequent years—there were widespread rumours during 1154 that William planned to assassinate Henry, for example.[221] Historian Graham White describes the treaty of Winchester as a "precarious peace", capturing the judgement of most modern historians that the situation in late 1153 was still uncertain and unpredictable.[222] Nonetheless, Stephen burst into activity in early 1154, travelling around the kingdom extensively.[223] He began issuing royal writs for the south-west of England once again and travelled to York where he held a major court in an attempt to impress upon the northern barons that royal authority was being reasserted.[221] In 1154, Stephen travelled to Dover to meet the Count of Flanders; some historians believe that the king was already ill and preparing to settle his family affairs.[224] Stephen fell ill with a stomach disorder and died on 25 October.[224]

Henry did not feel it necessary to hurry back to England immediately. On landing on 8 December 1154, Henry quickly took oaths of loyalty from some of the barons and was then crowned alongside Eleanor at Westminster.[225] The royal court was gathered in April 1155, where the barons swore fealty to the king and his sons.[225] Henry presented himself as the legitimate heir to Henry I and commenced rebuilding the kingdom in his image.[226] Although Stephen had tried to continue Henry I's method of government during the war, the new government characterised the 19 years of Stephen's reign as a chaotic and troubled period, with all these problems resulting from Stephen's usurpation of the throne.[227] Henry was also careful to show that, unlike his mother the Empress, he would listen to the advice and counsel of others.[228] Various measures were immediately carried out, although, since Henry spent six and a half of the first eight years of his reign in France, much work had to be done at a distance.[229]

England had suffered extensively during the war. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle recorded how "there was nothing but disturbance and wickedness and robbery".[230] Certainly in many parts of the country, such as the South-West, the Thames Valley and East Anglia, the fighting and raiding had caused serious devastation.[231] The previously centralised royal coinage system was fragmented, with Stephen, the Empress and local lords all minting their own coins.[231] The royal forest law had collapsed in large parts of the country.[232] Some parts of the country, though, were barely touched by the conflict—for example, Stephen's lands in the south-east and the Angevin heartlands around Gloucester and Bristol were largely unaffected, and David I ruled his territories in the north of England effectively.[231] The king's overall income from his estates declined seriously during the conflict, particularly after 1141, and royal control over the minting of new coins remained limited outside of the south-east and East Anglia.[233] With Stephen often based in the south-east, increasingly Westminster, rather than the older site of Winchester, was used as the centre of royal government.[234]

Among Henry's first measures was to expel the remaining foreign mercenaries and continue the process of demolishing the unauthorised castles.[235][nb 15] Robert of Torigni recorded that 375 were destroyed, without giving the details behind the figure; recent studies of selected regions have suggested that fewer castles were probably destroyed than once thought and that many may simply have been abandoned at the end of the conflict.[235] Henry also gave a high priority to restoring the royal finances, reviving Henry I's financial processes and attempting to improve the standard of the accounts.[236] By the 1160s, this process of financial recovery was essentially complete.[237]

The post-war period also saw a surge of activity around the English borders. The king of Scotland and local Welsh rulers had taken advantage of the long civil war in England to seize disputed lands; Henry set about reversing this trend.[238] In 1157 pressure from Henry resulted in the young Malcolm IV of Scotland returning the lands in the north of England he had taken during the war; Henry promptly began to refortify the northern frontier.[239] Restoring Anglo-Norman supremacy in Wales proved harder, and Henry had to fight two campaigns in north and south Wales in 1157 and 1158 before the Welsh princes Owain Gwynedd and Rhys ap Gruffydd submitted to his rule, agreeing to the pre-civil war division of lands.[240]

Legacy

Historiography

Much of the modern history of the civil war of the Anarchy is based on accounts of chroniclers who lived in, or close to, the middle of the 12th century, forming a relatively rich account of the period.[241] All of the main chronicler accounts carry significant regional biases in how they portray the disparate events. Several of the key chronicles were written in the south-west of England, including the Gesta Stephani, or "Acts of Stephen", and William of Malmesbury's Historia Novella, or "New History".[242] In Normandy, Orderic Vitalis wrote his Ecclesiastical History, covering the period until 1141, and Robert of Torigni wrote a later history of the rest of the later years.[242] Henry of Huntingdon, who lived in the east of England, produced the Historia Anglorum that provides a regional account of the conflict.[243] The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle was past its prime by the time of the war, but is remembered for its striking account of conditions during the Anarchy, in particular its description that "men said openly that Christ and his saints were asleep".[244] Most of the chronicles carry some bias for or against the key political figures in the conflict.[245]

The use of the term "the Anarchy" to describe the civil war has been subject to much critical discussion. The phrase itself originates in the late Victorian period. Many historians of the time traced a progressive and universalist course of political and economic development in England over the medieval period.[246] William Stubbs, following in this "Whiggish" tradition, analysed the political aspects of the period in his 1874 volume the Constitutional History of England. This work highlighted an apparent break in the development of the English constitution in the 1140s, and caused his student John Round to coin the term "the Anarchy" to describe the period.[247] Later historians critiqued the term, as analysis of the financial records and other documents from the period suggested that the breakdown in law and order during the conflict had been more nuanced and localised than chronicler accounts alone might have suggested.[248] Further work in the 1990s reinterpreted Henry's efforts in the post-war reconstruction period, suggesting a greater level of continuity with Stephen's wartime government than had previously been supposed.[249] The label of "the Anarchy" remains in use by modern historians, but rarely without qualification.[250]

Popular representations

The civil war years of the Anarchy have been occasionally used in historical fiction. Stephen, Matilda and their supporters feature in Ellis Peters's historical detective series about Brother Cadfael, set between 1137 and 1145.[251] Peters's depiction of the civil war is an essentially local narrative, focused on Shrewsbury and its environs.[251] Peters paints Stephen as a tolerant man and a reasonable ruler, despite his execution of the Shrewsbury defenders after taking the town in 1138.[252] In contrast, Ken Follett's historical novel The Pillars of the Earth and the TV mini-series based on it depict Stephen as an incapable ruler. Although Follett begins his book with Austin Poole's account of the White Ship's sinking to set the historical scene for the subsequent events, in many other ways Follett uses the war as a location for a story about essentially modern personalities and issues, a feature reproduced in the epic costume TV adaptation.[253]

Notes

- There has been extensive speculation as to the cause of the sinking of the White Ship. Some theories centre on overcrowding, while others blame excessive drinking by the ship's master and crew.[7]

- Modern historians, such as Edmund King, doubt that Hugh Bigod was being truthful in his account.[33]

- Opinions vary over the degree to which Stephen's acquisition of power resembled a coup. Frank Barlow, for example, describes it as a straightforward coup d'état; King is less certain that this is an appropriate description of events.[35]

- The events in Normandy are less well recorded than elsewhere, and the exact sequence of events less certain. Historian Robert Helmerichs, for example, describes some of the inconsistencies in these accounts. Some historians, including David Crouch and Helmerichs, argue that Theobald and Stephen had probably already made a private deal to seize the throne when Henry died.[40]

- Geoffrey of Anjou appears to have agreed to this at least partially because of the pressure of the combined Anglo-Norman-French regional alliance against him.[61] Medieval financial figures are notoriously hard to convert into modern currency; for comparison, 2,000 marks equated to around £1,333 in a period in which a major castle rebuilding project might cost around £1,115.[62]

- David I was related to the Empress Matilda and to Matilda of Boulogne through his mother, Queen Margaret.

- R. Davis and W. L. Warren argue that the typical earldom involved the delegation of considerable royal powers; Keith Stringer and Judith Green capture the current consensus that the degree of delegated powers followed the degree of threat, and that perhaps fewer powers in total were delegated than once thought.[77]

- The impact of these arrests on the efficacy of the subsequent royal administration and the loyalty of the wider English church has been much discussed. Kenji Yoshitake represents the current academic consensus when he notes that the impact of the arrests "was not serious", placing the beginning of the disintegration of the royal government at the subsequent Battle of Lincoln.[83]

- Keith Stringer argues that Stephen "was surely right" to seize the castles, and that the act was a "calculated display of royal masterfulness"; Jim Bradbury and Frank Barlow praise the military soundness of the tactic. David Carpenter and R. Davis observe that Stephen had ended up breaking his promises to the Church, was forced to appear before a church court, and damaged his relationship with Henry of Blois, which would have grave implications in 1141.[85]

- Edmund King disagrees about that the Empress received an invitation to Arundel, arguing that she appeared unexpectedly.[116]

- "Chivalry" was firmly established as a principle in Anglo-Norman warfare by the time of Stephen; it was not considered appropriate or normal to execute elite prisoners and, as historian John Gillingham observes, neither Stephen nor the Empress Matilda did so except where the opponent had already breached the norms of military conduct.[121]

- David Crouch argues that in fact it was the royalist weakness in infantry that caused their failure at Lincoln, proposing the city militia was not as capable as Robert's Welsh infantry.[137]

- The degree to which Stephen's supporters at the Battle of Lincoln simply fled, wisely retreated or in fact actively betrayed him to the enemy has been extensively debated.[141]

- Edmund King believes the attack never got close to York; R. Davis believes that it did and was deterred by the presence of Stephen's forces.[198]

- Recent research has shown that Stephen had begun the programme of castle destruction before his death and that Henry's contribution was less substantial than once thought, although Henry did take much of the credit for this programme of work.[235]

References

- Bradbury, p.215.

- Barlow, p.111; Koziol, p.17; Thompson, p.3.

- Carpenter, p.137.

- Huscroft, p.69.

- Carpenter, pp.142–143.

- Bradbury, pp.1–3.

- Bradbury, p.2.

- Barlow, p.162.

- Huscroft, pp.65, 69–71; Carpenter, p.125.

- Bradbury, p.3; Chibnall, p.64.

- Bradbury, pp.6–7.

- Barlow, p.160; Chibnall, p.33.

- Barlow, p.161.

- Carpenter, p.160.

- Carpenter, p.161; Stringer, p.8.

- Bradbury, p.9; Barlow, p.161.

- King (2010), pp.30–31; Barlow, p.161.

- King (2010), pp.38–39.

- King (2010), p.38; Crouch (2008a), p.162.

- King (2010), p.13.

- Davis, p.8.

- King (2010), p.29.

- Stringer, p.66.

- Crouch (2002), p.246.

- Chibnall, pp.66–67.

- Barlow, pp.163–164.

- Barlow, p.163; King (2010), p.43.

- King (2010), p.43.

- King (2010), p.45.

- King (2010), pp.45–46.

- King (2010), p.46.

- Crouch (2002), p.247.

- King (2010), p.52.

- King (2010), p.47.

- Barlow, p.165; King (2010), p.46.

- King (2010), pp.46–47.

- King (2010), p.47; Barlow, p.163.

- Barlow, p.163.

- Barlow, p.163; Carpenter, p.168.

- Helmerichs, pp.136–137; Crouch (2002), p.245.

- Carpenter, p.165.

- King (2010), p.53.

- King (2010), p.57.

- King (2010), pp.57–60; Davis, p.22.

- Carpenter, p.167.

- White (2000), p.78.

- Crouch (2002), p.250.

- Crouch (2008a), p.29; King (2010), pp.54–55.

- Crouch (2008b), pp.46–47.

- Crouch (2002), pp.248–249.

- Carpenter, pp.164–165; Crouch (1998), p.258.

- Crouch (1998), pp.260, 262.

- Bradbury, pp.27–32.

- Barlow, p.168.

- Crouch (2008b), pp.46–47; Crouch (2002), p.252.

- Crouch (2008b), p.47.

- Barlow, p.168;

- Davis, p.27.

- Davis, p.27; Bennett, p.102.

- Davis, p.28.

- Crouch (2008b), p.50; Barlow, p.168.

- Pettifer, p.257.

- Barlow, pp.165, 167; Stringer, pp.17–18.

- Barlow, p.168; Crouch (1998), p.264; Carpenter, p.168.

- Carpenter, p.169.

- Barlow, p.169.

- Stringer, p.18.

- Chibnall, pp.70–71; Bradbury, p.25.

- Carpenter, p.166.

- Bradbury, p.67.

- Crouch (2002), p.256.

- Davis, p.50.

- Chibnall, p.74.

- Chibnall, pp.75–76.

- Bradbury, p.52.

- Bradbury, p.70.

- White (2000), pp.76–77.

- Barlow, pp.171–172; Crouch (2008a), p.29.

- Barlow, p.172.

- Davis, p.31.

- Davis, p.32.

- Yoshitake, p.98.

- Yoshitake, pp.97–98; 108–109.

- Davis, p.34; Barlow, p.173.

- Stringer, p.20; Bradbury, p.61; Davis, p.35; Barlow, p.173; Carpenter, p.170.

- Bradbury, p.71.

- Morillo, pp.16–17.

- Stringer, pp.24–25.

- Morillo, pp.51–52.

- Bradbury, p.74.

- Morillo, p.52.

- Prior ref.

- Bradbury, p.73.

- Walker, p.15.

- Creighton, p.59.

- Coulson, p.69.

- Coulson, p.69; Bradbury, p.191.

- Bradbury, p.28.

- Creighton and Wright, p.53.

- Creighton, p.56.

- Creighton, p.57.

- Creighton and Wright, pp.56–57, 59.

- King (2010), p.301.

- Stringer, pp.15–16; Davis, p.127.

- Barlow, p.167.

- Carpenter, p.172.

- Chibnall, pp.26, 33.

- Chibnall, p.97.

- Chibnall, pp.62–63.

- Chibnall, p.63.

- Chibnall, pp.58–59.

- King (2010), pp.61–62.

- Davis, p.40; Chibnall, p.82.

- Chibnall, pp.85–87; Bradbury, p.50.

- Davis, p.39.

- King (2010), p.116.

- Davis, p.40.

- Bradbury, p.78.

- Bradbury, p.79.

- Gillingham (1994), p.31.

- Gillingham (1994), pp.49–50.

- Bradbury, p.81.

- Chibnall, p.83-84

- Bradbury, p.82; Davis, p.47.

- Bradbury, p.83.

- Bradbury, pp.82–83.

- Davis, p.42.

- Davis, p.43.

- Bradbury, p.88.

- Bradbury, p.90.

- Chibnall, p.92.

- Bradbury, p.91.

- Davis, pp.50–51.

- Davis, p.51.

- Davis, p.52.

- Bradbury, p.105.

- Crouch (2002), p.260.

- Bradbury, p.104.

- Bradbury, p.108.

- Bradbury, pp.108–109.

- Bennett, p.105.

- King (2010), p.154.

- King (2010), p.155.

- King (2010), p.156.

- King (2010), p.175; Davis, p.57.

- King (2010), p.158; Carpenter, p.171.

- Chibnall, pp.98–99.

- Chibnall, p.98.

- Chibnall, p.102.

- Chibnall, p.103.

- King (2010), p.163; Chibnall, p.104-105.

- Carpenter, p.173; Davis, p.68; Crouch (2008b), p.47.

- Crouch (2008b), p.52.

- Davis, p.67.

- Davis, pp.67–68.

- Blackburn, p.199.

- Crouch (2002), p.261.

- Bennett, p.106; Crouch (2002), p.261.

- Barlow, p.176.

- Bradbury, p.121.

- Barlow, p.176; Chibnall, p.113.

- Chibnall, p.113.

- Barlow, p.177; Chibnall, p.114.

- Barlow, p.177.

- Barlow, p.177; Chibnall, p.115.

- Bradbury, pp.134, 136.

- Barlow, p.178.

- Bradbury, p.136.

- Chibnall, pp.116–117.

- Bradbury, p.137.

- Chibnall, p.117.

- Davis, p.78.

- Bradbury, p.139.

- Bradbury, p.140.

- Bradbury, pp.140–141.

- Bradbury, p.141.

- Bradbury, p.143.

- Bradbury, p.144.

- Bradbury, p.145.

- Barlow, p.179.

- Amt, p.7.

- Crouch (2002), p.269; White (1998), p.133.

- Bradbury, p.158.

- Bradbury, p.147.

- Bradbury, p.146.

- Davis, p.97.

- Barlow, p.180.

- Barlow, p.180; Chibnall, pp.148–149.

- Davis, pp.111–112.

- King (2010), p.243; Barlow, p.180.

- Davis, pp.111–113.

- Davis, p.112.

- Davis, p.113.

- Chibnall, pp.141, 151–152.

- King (2010), p.253.

- King (2010), p.254.

- King (2010), p.255.

- Davis, p.107; King (2010), p.255.

- Carpenter, p.188.

- King (2010), p.237.

- Davis, p.105.

- Davis,. p.105; Stringer, p.68.

- Davis, pp.100–102.

- King (2010), p.264.

- Bradbury, pp.178–179.

- Bradbury, p.180.

- Bradbury, p.181.

- King (2007), pp.25–26.

- King (2007), p.26.

- Bradbury, p.182.

- Bradbury, p.183.

- Bradbury, p.183; King (2010), p.277; Crouch (2002), p.276.

- King (2010), pp.278–279; Crouch (2002), p.276.

- King (2010), p.278.

- Bradbury, p.184.

- King (2010), pp.279–280; Bradbury, p.187.

- King (2010), p.280.

- King (2010), pp.280–283; Bradbury pp.189–190; Barlow, pp.187–188.

- King (2010), p.281.

- Bradbury, p.211; Holt, p.306.

- Crouch (2002), p.277.

- White (1990), p.12, cited Bradbury, p.211.

- Amt, p.19.

- King (2010), p.300.

- White (2000), p.5.

- White (2000), p.2.

- White (2000), pp.2–3.

- King (2007), pp.42–43.

- White (2000), p.8.

- Huscroft, p.76.

- Barlow, p.181.

- Carpenter, p.197.

- White (1998), p.43; Blackburn, p.199.

- Green, pp.110–111, cited White (2008), p.132.

- Amt, p.44.

- White (2000), pp.130, 159.

- Barratt, p.249.

- Warren (2000), p.161.

- White (2000), p.7; Carpenter, p.211.

- White (2000), p.7; Huscroft, p.140; Carpenter, p.214.

- King (2006), p.195.

- Davis, p.146.

- Davis, pp.147, 150.

- Davis, p.151; Bradbury, p.215.

- Davis, pp.146–152.

- Dyer, p.4; Coss, p.81.

- Review of King Stephen, (review no. 1038), David Crouch, Reviews in History, accessed 12 May 2011; Kadish, p.40; Round (1888), cited Review of King Stephen, (review no. 1038), David Crouch, Reviews in History, accessed 12 May 2011.

- White (2000), pp.14–15; Hollister, pp.51–54.

- White (2000), pp.75–76.

- White (2000), p.12; Carpenter, p.176; King (1994), p.1.

- Rielly, p.62.

- Rielly, p.68.

- Turner, p.122; Ramet, p.108; Blood on Their Hands, and Sex on Their Minds, Mike Hale, The New York Times, published 22 July 2010, accessed 15 May 2011.

Bibliography