Wallingford Castle

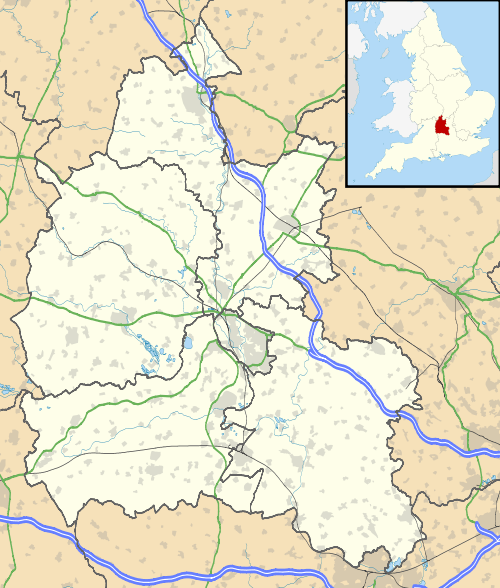

Wallingford Castle was a major medieval castle situated in Wallingford in the English county of Oxfordshire (historically in Berkshire until the 1974 reorganisation), adjacent to the River Thames. Established in the 11th century as a motte-and-bailey design within an Anglo-Saxon burgh, it grew to become what historian Nicholas Brooks has described as "one of the most powerful royal castles of the 12th and 13th centuries".[1] Held for the Empress Matilda during the civil war years of the Anarchy, it survived multiple sieges and was never taken. Over the next two centuries it became a luxurious castle, used by royalty and their immediate family. After being abandoned as a royal residence by Henry VIII, the castle fell into decline. Refortified during the English Civil War, it was eventually slighted, i.e. deliberately destroyed, after being captured by Parliamentary forces after a long siege. The site was subsequently left relatively undeveloped, and the limited remains of the castle walls and the considerable earthworks are now open to the public.

| Wallingford Castle | |

|---|---|

| Oxfordshire, England | |

Ruins of Wallingford Caste | |

Wallingford Castle | |

| Coordinates | 51.6029°N 1.1221°W |

| Grid reference | grid reference SU609897 |

| Type | Motte-and-bailey |

| Site information | |

| Condition | Ruined |

| Site history | |

| Battles/wars | The Anarchy, English Civil War |

History

11th century

As an important regional town, overlooking a key crossing point on the River Thames, prosperous and with its own mint, the town of Wallingford had been defended by an Anglo-Saxon burgh, or town wall, prior to the Norman invasion of 1066.[2] Wigod of Wallingford, who controlled the town, supported William the Conqueror's invasion and entertained the king when he arrived in Wallingford.[3] Immediately after the end of the initial invasion, the king set about establishing control over the Thames Valley through constructing three key castles, the royal castles of Windsor and Wallingford, and the baronial castle, later transferred to royal hands, built at Oxford.[4]

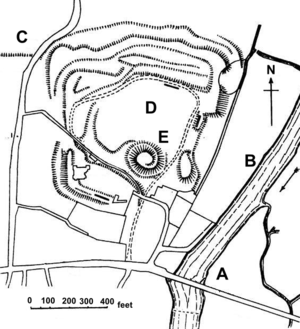

Wallingford Castle was probably built by Robert D'Oyly between 1067 and 1071. Robert had married Wigod's daughter Ealdgyth, and ultimately inherited many of his father-in-law's lands.[3] The wooden castle was built in the north-east corner of the town, taking advantage of the old Anglo-Saxon ramparts, with the motte close to the river overlooking the ford, and required substantial demolition work to make room for the new motte-and-bailey structure.[5] Unusually, it appears that the castle was constructed on top of high-status Anglo-Saxon housing, probably belonging to former housecarls.[6] The motte today is 60 metres (197 feet) across and 13 metres (43 feet) high.[7] Robert endowed a sixteen-strong college of priests within the castle, which he named St Nicholas College.[8]

12th century

Wallingford Castle passed from Robert to first his son-in-law Miles Crispin, and then Brien FitzCount, who married Robert's daughter after Miles died.[3] Brien, an important supporter of Henry I, was the son of the Duke of Brittany, and probably strengthened the castle in stone in the 1130s.[9] He produced a very powerful fortification, including a shell keep and a curtain wall around the bailey, that, combined with the extensive earthworks, has been described by historian Nicholas Brooks as "one of the most powerful royal castles of the 12th and 13th centuries".[10]

After the death of Henry, however, the political situation in England became less stable, with both Stephen of England and the Empress Matilda laying claim to the throne. Brien had originally been considered a supporter of Stephen, but in 1139 Matilda travelled to England and Brien announced his allegiance to her, joining forces with Miles of Gloucester and other supporters in the south-west.[3] Wallingford Castle was now the most easterly stronghold of the Empress's faction – it was either the closest base to London, or the first in line to be attacked by Stephen's forces, depending on one's perspective.[11]

Stephen attacked the castle in 1139, initially intending to besiege it, as the walls were considered impregnable to assault.[12] Brien had brought in considerable supplies – contemporaries believed the castle could survive a siege for several years if need be – and Stephen changed his mind, putting up two counter-castles to contain Wallingford along the road to Bristol, before continuing west.[13] The next year, Miles of Gloucester, possibly acting under orders from Robert of Gloucester, struck east, destroying one of the counter-castles outside Wallingford.[14] The civil war between Stephen and Matilda rapidly descended into an attritional campaign, in which castles like Wallingford played a critical role in efforts by both sides to secure the Thames Valley.[15] After the fall of Oxford to Stephen in 1141, Matilda fled to Wallingford, and the importance of the castle continued to grow.[3]

Around this time Brien established a notorious prison within the castle, called Cloere Brien, or "Brien's Close", as part of his efforts to extract money and resources from the surrounding region.[3] The nobleman William Martel, Stephen's royal steward, was one of the most high-profile prisoners to be kept there.[16] Contemporary chroniclers reported the cries of tortured prisoners in the castle disturbed the inhabitants of the town of Wallingford.[3] There was not enough space in the castle for all of Brien's forces, and various houses in the town had to be taken for the use of his knights.[17]

Between 1145 and 1146 Stephen made another attempt to seize Wallingford, but was again unable to take the castle despite building a powerful counter-castle to the east, opposite Wallingford at Crowmarsh Gifford, and building castles to the west at Brightwell, South Moreton and Cholsey.[18] He returned with larger forces in 1152, reestablishing the counter-castle at Crowmarsh Gifford and building another one overlooking Wallingford bridge, and settled his forces down to starve the castle out.[19] Brien, supported by Miles' son, Roger of Hereford, who had also become trapped in the castle, attempted to break through the blockade, but without success.[20]

By 1153, the castle garrison was running very low on food, and Roger made a deal with Stephen allowing him to leave the castle with his followers.[20] Henry, the Empress' son and the future Henry II, then intervened, marching his forces to relieve the castle and placing Stephen's counter-castles under siege himself.[21] King Stephen marched back from Oxford, and the two forces confronted each other on the meadows outside the castle.[3] The result was an embryonic peace deal called the Treaty of Wallingford, leading on to the permanent Treaty of Winchester that would ultimately bring an end to the civil war and install Henry as king following Stephen's death in 1153.[22] Brien, who had no children, chose to enter a monastery, and surrendered Wallingford Castle to Henry at the end of the conflict in 1153.[3]

At the end of the 12th century, the castle become closely associated with King John, who had been granted the town by Richard I in 1189. John seized the castle as well during his revolt in 1191, and although he was forced to return it, he reclaimed it when he became king himself in 1199. John made extensive use of Wallingford Castle during the First Barons' War between 1215 and 1216, reinforcing the fortifications and mobilising a substantial garrison to protect it.[3]

13th–15th centuries

Under Henry III, Richard, the 1st Earl of Cornwall was formally granted the castle as his main residence in 1231. Richard lived in considerable style, and spent substantial sums on the property, building a new hall and more luxurious fittings. Richard's election as King of the Romans in 1251 brought an end to his use of the property, but the castle became embroiled in the Second Barons' War in the 1260s. Simon de Montfort seized the castle after his victory at the battle of Lewes, using it to imprison the royal family for a time, before moving them to the more secure Kenilworth Castle. Reclaimed by Henry III at the end of the conflict, it continued to be used by the Earls of Cornwall as a luxurious home for the rest of the century.[3]

Edward II gave Wallingford Castle first to his royal favourite, Piers Gaveston, and then to his young wife, Isabella of France, with large sums still being spent on the property. Edward continued to use the castle as a royal prison for holding his enemies, until his own fall from power in 1326; Isabella, who overthrew her husband, then used it as an early headquarters following her invasion of England. Her son, Edward III, ultimately settled the castle on the new title of the Duke of Cornwall, used by sons of the king.[3]

The castle continued to be used as a county jail, with many complaints about the number of felons who were able to escape from it. The cost of maintaining the castle from local rents and revenues became more challenging towards the end of the 14th century, with additional royal revenues being required for the ongoing work required on it.[3] Nonetheless, in 1399 when Richard II was deposed, the castle was well fortified and in good condition, forming what historian Douglas Biggs calls "a formidable obstacle" to Richard's enemies, and able to host the royal government when it first fled from London.[23] Wallingford Castle played little role in the Wars of the Roses and after Henry VIII used it for a final time in 1518 it appears to have fallen into disuse as a royal residence.[3]

16th–19th centuries

The castle fell into decline in the 16th century; it was separated from the Duchy of Cornwall, and under Queen Mary the site was stripped for lead and other building materials for use at Windsor Castle. The antiquarian John Leland described the castle in 1540 as being "nowe sore yn ruine, and for the most part defaced", although the jail continued in use throughout the period, albeit still suffering from many escapee inmates. Held by various nobles from 1600 onwards, it returned to the crown under Charles I, who gave it to Queen Henrietta Maria, but by then the castle was only really valuable for the surrounding meadow land and fisheries.[3]

The English Civil War broke out between the supporters of Charles I and Parliament in the 1640s; with the king and Parliament maintaining their capitals in Oxford and London respectively, the Thames Valley once again became a critical war zone. Wallingford was a Royalist town, with a garrison established there in 1642 to prevent an advance on Oxford to the north-west.[24] Colonel Thomas Blagge was appointed governor, and in 1643 the king instructed him to refortify the castle, inspecting the results later that year. By 1644, the surrounding Thames towns of Abingdon and Reading had fallen and Parliamentary forces unsuccessfully attacked the town and castle of Wallingford in 1645. General Thomas Fairfax placed Wallingford Castle under siege the next year; after 16 weeks, during which Oxford fell to Parliamentary forces, the castle finally surrendered in July 1646 under generous terms for the defenders.[3]

The risk of civil conflict continued, however, and Parliament decided that it was necessary to slight, or damage so as to put beyond military use, the castle in 1652, as it remained a surprisingly powerful fortress and a continuing threat should any fresh uprising occur.[25] The castle was virtually razed to the ground in the operation, although a brick building continued to be used as a prison into the 18th century.[26] A large house was built in the bailey in 1700, followed by a gothic mansion house on the same site in 1837.[27]

Today

The mansion, abandoned due to rising costs, was demolished in 1972, allowing Wallingford Castle to be declared a scheduled monument as well as a Grade I listed building.[7] The castle grounds, including the remains of St Nicholas College, two sections of castle wall and the motte hill, are now open to the public. An archaeological research project run by Leicester University conducted a sequence of excavations between 2002 and 2010, aiming to better understand the historical transition from the Anglo-Saxon town of Wallingford and the burgh, to the period of the Norman castle.[28] The castle's motte was investigated by the Round Mounds Project during 2015 and 2016, whose results confirmed the mounds Norman origins.[29]

The grounds - Wallingford Castle Meadows - are managed by environmental learning charity Earth Trust on behalf of South Oxfordshire District Council.[30]

See also

- Castles in Great Britain and Ireland

- List of castles in England

- List of lords of Wallingford Castle

- List of prisoners at Wallingford Castle

References

- Brooks, p.17.

- Durham, Hassal, Rowley and Simpson (1972), p.82; The Borough of Wallingford: Introduction and Castle, A History of the County of Berkshire: Volume 3 (1923), pp. 517–531, accessed 26 April 2011.

- The Borough of Wallingford: Introduction and Castle, A History of the County of Berkshire: Volume 3 (1923), pp. 517–531, accessed 26 April 2011.

- Emery, p.15.

- Armitage, p.437; Pounds, p.207.

- Creighton, p.140.

- Wallingford Castle, the Gatehouse website, accessed 26 April 2011; Rowley and Breakell, p.159.

- Pounds, p.235.

- Keats-Rohan, p.315; Bradbury, p.82.

- Keats-Rohan, p.315; Bradbury, p.82; Brooks, p.17; 'Wallingford Castle, the Gatehouse website, accessed 3 July 2011.

- Bradbury, pp.82–3.

- Bradbury, p.83; Slade, p.34.

- Bradbury, p.83; Hosler, p.43.

- Bradbury, p.90.

- Bradbury, p.133.

- Slade, p.40.

- Slade, p.39.

- The Borough of Wallingford: Introduction and Castle, A History of the County of Berkshire: Volume 3 (1923), pp. 517–531, accessed 26 April 2011; Spurrell, pp.269–270.

- Bradbury, p.182; Hosler, p.43.

- Bradbury, p.182.

- Bradbury, p.183.

- Bradbury, p.184.

- Biggs, p.130.

- Newman, p.31.

- Lysons, p.397.

- Lysons, p.397; The Borough of Wallingford: Introduction and Castle, A History of the County of Berkshire: Volume 3 (1923), pp. 517–531, accessed 26 April 2011.

- Rowley and Breakell, p.158.

- Wallingford Burh to Borough Research Project, University of Leicester, accessed 3 July 2011; The Big Dig: Wallingford, Archaeology, Oliver Creighton, Neil Christie, Matt Edgeworth and Helena Hamerow, accessed 3 July 2011.

- Leary, Jamieson and Stastney.

- Wallingford Castle Meadows, South Oxfordshire District Council, accessed 2 August 2016.

Bibliography

- Armitage, Ella. (1912) The Early Norman Castles of the British Isles. London: John Murray.

- Biggs, Douglas. (2002) "'To Aid the Custodian and Council': Edmund of Langley and the Defence of the Realm, June – July 1399," in Rogers, Bachrch and Devries (eds) (2002).

- Bradbury, Jim. (2009) Stephen and Matilda: the Civil War of 1139–53. Stroud, UK: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7509-3793-1.

- Brooks, N.P. (1966) "Excavations at Wallingford Castle, 1965: an Interim Report," Berkshire Archaeological Journal 62, pp. 17–21.

- Creighton, Oliver Hamilton. (2005) Castles and Landscapes: Power, Community and Fortification in Medieval England. London: Equinox. ISBN 978-1-904768-67-8.

- Durham, B., T. G. Hassall, T. Rowley and C. Simpson. (1972) "A Cutting Across the Saxon Defences at Wallingford," Oxoniensia Vol 37, pp. 82–5.

- Emery, Anthony. (2006) Greater Medieval Houses of England and Wales, 1300–1500: Southern England. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-58132-5.

- Keats-Rohan, K.S.B. (1989) "The Devolution of the Honour of Wallingford, 1066–1148." Oxoniensia 54, pp. 311–318.

- Hosler, John D. (2007) Henry II: a Medieval Soldier at War, 1147–1189. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-15724-8.

- Leary, Jim; Elaine Jamieson and Phil Stastney. (2018) "Normal for Normans? Exploring the Large Round Mounds of England," Current Archaeology 337.

- Lysons, Daniel. (1813) Magna Britannia: Vol. I Part II. London: T. Cadell.

- Newman, P. R. (1998) Atlas of the English Civil War. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-19610-9.

- Pounds, Norman John Greville. (1994) The Medieval Castle in England and Wales: a Social and Political History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-45828-3.

- Rogers, Clifford J, Bernard S. Bachrach, Kelly DeVries. (eds) (2002) Journal of Medieval Military History I. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-85115-909-6.

- Rowley, Trevor and Mike Breakell. (1977) Planning and the Historic Environment II. Oxford: Oxford University Department for External Studies. ISBN 978-0-903736-05-3.

- Slade, C.F. (1960) "Wallingford Castle in the Reign of Stephen," Berkshire Archaeological Journal 58, pp. 33–43.

- Spurrell, M. (1995) "Containing Wallingford Castle, 1146–53.", Oxoniensia 60, pp. 257–270.

Further reading

- Christie, Neil Creighton, Oliver Hamilton, Edgeworth, Matt and Hamerow, Helena (2013) Transforming Townscapes: From burh to borough: the archaeology of Wallingford, AD 800–1400. Society for Medieval Archaeology Monographs volume 35. ISBN 9781909662094

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wallingford Castle. |

- Wallingford History Gateway

- Royal Berkshire History: Wallingford Castle

- Wallingford Castle - Community meadow and reserve information from Earth Trust