Anjou

Anjou (UK: /ˈɒ̃ʒuː, ˈæ̃ʒuː/, US: /ɒ̃ˈʒuː, ˈæn(d)ʒuː, ˈɑːnʒuː/;[1][2][3] French: [ɑ̃ʒu]; Latin: Andegavia) was a French province straddling the lower Loire River. Its capital was Angers and it was roughly coextensive with the diocese of Angers. Anjou was bordered by Brittany to the west, Maine to the north, Touraine to the east and Poitou to the south. The adjectival form is Angevin, and inhabitants of Anjou are known as Angevins. During the Middle Ages, the County of Anjou, ruled by the Counts of Anjou, was a prominent fief of the French crown.

Anjou | |

|---|---|

Province | |

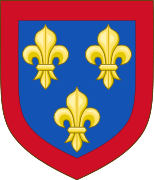

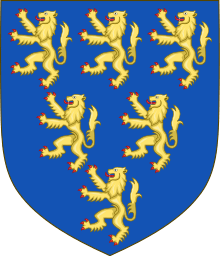

Flag  Coat of arms | |

| Etymology: Territory of Angers | |

.svg.png) The Province of Anjou in 1789. | |

| Established | 929 |

| Dissolved | 1790 |

| Seat | Angers |

| Government | |

| • Type | Feudal administrative province |

| • Counts/Dukes | Ingelger (first) Louis XVI (last) |

| Demonym(s) | Angevins |

The region takes its name from the Celtic tribe of the Andecavi, which submitted to Roman rule following the Gallic Wars. Under the Romans, the chief fortified settlement of the Andecavi became the city of Juliomagus, the future Angers. The territory of the Andecavi was organized as a civitas (called the civitas Andegavensis or civitas Andegavorum).

Under the Franks, the city of Juliomagus took the name of the ancient tribe and became Angers. Under the Merovingians, the history of Anjou is obscure. It is not recorded as a county (comitatus) until the time of the Carolingians. In the late ninth and early tenth centuries the viscounts (representatives of the counts) usurped comital authority and made Anjou an autonomous hereditary principality. The first dynasty of counts of Anjou, the House of Ingelger, ruled continuously down to 1205. In 1131, Count Fulk V became the King of Jerusalem; then in 1154, his grandson, Henry "Curtmantle" became King of England. The territories ruled by Henry and his successors, which stretched from Ireland to the Pyrenees, are often called the Angevin Empire. This empire was broken up by the French king Philip II, who confiscated the dynasty's northern French lands, including Anjou in 1205.

The county of Anjou was united to the royal domain between 1205 and 1246, when it was turned into an apanage for the king's brother, Charles I of Anjou. This second Angevin dynasty, a branch of the Capetian dynasty, established itself on the throne of Naples and Hungary. Anjou itself was united to the royal domain again in 1328, but was detached in 1360 as the Duchy of Anjou for the king's son, Louis I of Anjou. The third Angevin dynasty, a branch of the House of Valois, also ruled for a time the Kingdom of Naples. The dukes had the same autonomy as the earlier counts, but the duchy was increasingly administered in the same fashion as the royal domain and the royal government often exercised the ducal power while the dukes were away. When the Valois line failed and Anjou was incorporated into the royal domain again in 1480, there was little change on the ground. Anjou remained a province of crown until the French Revolution (1790), when the provinces were reorganized.

Position

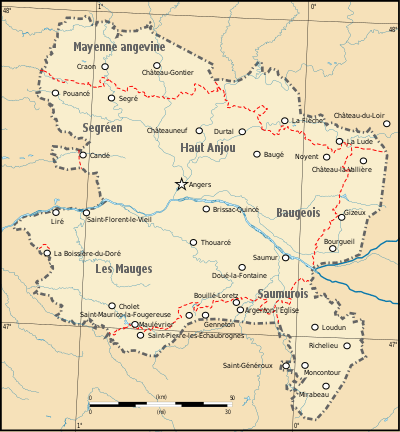

Under the kingdom of France, Anjou was practically identical with the diocese of Angers, bound on the north by Maine, on the east by Touraine, on the south by Poitou (Poitiers) and the Mauges, and the west by the countship of Nantes or the duchy of Brittany.[4][5] Traditionally Anjou was divided into four natural regions: the Baugeois, the Haut-Anjou (or Segréen), the Mauges, and the Saumurois.

It occupied the greater part of what is now the department of Maine-et-Loire. On the north, it further included Craon, Candé, Bazouges (Château-Gontier), Le Lude; on the east, it further added Château-la-Vallière and Bourgueil; while to the south, it lacked the towns of Montreuil-Bellay, Vihiers, Cholet, and Beaupréau, as well as the district lying to the west of the Ironne and Thouet on the left bank of the Loire, which formed the territory of the Mauges.[5]

History

Gallic state

Anjou's political origin is traced to the ancient Gallic state of the Andes.[5]

Roman tribe

After the conquest by Julius Caesar, the area was organized around the Roman civitas of the Andecavi.[5]

Frankish county

The Roman civitas was afterward preserved as an administrative district under the Franks with the name first of pagus—then of comitatus or countship—of Anjou.[5]

At the beginning of the reign of Charles the Bald, the integrity of Anjou was seriously menaced by a twofold danger: from Brittany to the west and from Normandy to the north. Lambert, a former count of Nantes, devastated Anjou in concert with Nominoé, duke of Brittany. By the end of the year 851, he had succeeded in occupying all the western part as far as the Mayenne. The principality which he thus carved out for himself was occupied on his death by Erispoé, duke of Brittany. By him, it was handed down to his successors, in whose hands it remained until the beginning of the 10th century. The Normans raided the country continuously as well.[5]

A brave man was needed to defend it. The chroniclers of Anjou named a "Tertullus" as the first count, elevated from obscurity by Charles the Bald.[4] A figure by that name seems to have been the father of the later count Ingelger but his dynasty seems to have been preceded by Robert the Strong, who was given Anjou by Charles the Bald around 861. Robert met his death in 866 in a battle at Brissarthe against the Normans. Hugh the Abbot succeeded him in the countship of Anjou as in most of his other duties; on his death in 886, it passed to Odo, Robert's eldest son.[5]

The Fulks

Odo acceded to the throne of France in 888, but he seems to have already delegated the country between the Maine and the Mayenne to Ingelger as a viscount or count around 870,[4] possibly owing to the connections of his wife Adelais of Amboise.[6] Their son Fulk the Red succeeded to his father's holdings in 888,[4] is mentioned as a viscount after 898, and seems to have been granted or usurped the title of count by the second quarter of the 10th century. His descendants continued to bear that rank for three centuries. He was succeeded by his son Fulk II the Good, author of the proverb that an unlettered king is a wise ass, in 938.[4] He was succeeded in turn by his son Geoffrey I Grisegonelle ("Greytunic") around 958.[4]

Geoffrey inaugurated a policy of expansion, having as its objects the extension of the boundaries of the ancient countship and the reconquest of those parts of it which had been annexed by other states; for, though western Anjou had been recovered from the dukes of Brittany since the beginning of the 10th century, in the east all the district of Saumur had already by that time fallen into the hands of the counts of Blois and Tours. Geoffrey Greytunic succeeded in making the Count of Nantes his vassal and in obtaining from the Duke of Aquitaine the concession in fief of the district of Loudun. Moreover, in the wars of King Lothaire against the Normans and against the emperor Otto II, he distinguished himself by feats of arms which the epic poets were quick to celebrate.[5]

Geoffrey's son Fulk III Nerra ("the Black"; 21 July 987 – 21 June 1040) gained fame both as a warrior and for the pilgrimages he undertook to the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem to atone for his deeds.[4] He found himself confronted on his accession with a coalition of Odo I, count of Blois, and Conan I of Rennes. The latter having seized upon Nantes, of which the counts of Anjou held themselves to be suzerains, Fulk Nerra came and laid siege to it, routing Conan's army at the battle of Conquereuil (27 June 992) and re-establishing Nantes under his own suzerainty. Then turning his attention to the count of Blois, he proceeded to establish a fortress at Langeais, a few miles from Tours, from which, thanks to the intervention of the king Hugh Capet, Odo failed to oust him.

On the death of Odo I, Fulk seized Tours (996); but King Robert the Pious turned against him and took the town again (997). In 997 Fulk took the fortress of Montsoreau. In 1016 a fresh struggle arose between Fulk and Odo II, the new count of Blois. Odo II was utterly defeated at Pontlevoy (6 July 1016), and a few years later, while Odo was besieging Montboyau, Fulk surprised and took Saumur (1026).[5]

Finally, the victory gained by Geoffrey Martel (21 June 1040 – 14 November 1060), the son and successor of Fulk, over Theobald III, count of Blois, at Nouy (21 August 1044), assured to the Angevins the possession of the countship of Touraine. At the same time, continuing in this quarter also the work of his father (who in 1025 took prisoner Herbert Wakedog and only set him free on condition of his doing him homage), Geoffrey succeeded in reducing the countship of Maine to complete dependence on himself. During his father's life-time he had been beaten by Gervais de Château-du-Loir, bishop of Le Mans (1038), but later (1047 or 1048) succeeded in taking the latter prisoner, for which he was excommunicated by Pope Leo IX at the council of Reims (October 1049). He was a vigorous opponent of William the Bastard, when the latter was still merely the duke of Normandy.[4] Despite concerted attacks from William and from King Henry, he was able to force Maine to recognize his authority in 1051. He failed, however, in his attempts to revenge himself on William.[5]

On the death of Geoffrey Martel (14 November 1060), there was a dispute as to the succession. Geoffrey Martel, having no children, had bequeathed the countship to his eldest nephew, Geoffrey III the Bearded, son of Geoffrey, count of Gâtinais and of Ermengarde, daughter of Fulk Nerra. But Fulk le Réchin (the Cross-looking), brother of Geoffrey the Bearded, who had at first been contented with an appanage consisting of Saintonge and the châtellenie of Vihiers, having allowed Saintonge to be taken in 1062 by the duke of Aquitaine, took advantage of the general discontent aroused in the countship by the unskilful policy of Geoffrey to make himself master of Saumur (25 February 1067) and Angers (4 April), and cast Geoffrey into prison at Sablé. Compelled by the papal authority to release him after a short interval and to restore the countship to him, he soon renewed the struggle, beat Geoffrey near Brissac and shut him up in the castle of Chinon (1068). In order, however, to obtain his recognition as count, Fulk IV Réchin (1068 – 14 April 1109) had to carry on a long struggle with his barons, to cede Gâtinais to King Philip I, and to do homage to the count of Blois for Touraine. On the other hand, he was successful on the whole in pursuing the policy of Geoffrey Martel in Maine: after destroying La Flèche, by the peace of Blanchelande (1081), he received the homage of Robert Curthose ("Courteheuse"), son of William the Conqueror, for Maine. Later, he upheld Elias, lord of La Flèche, against William Rufus, king of England, and on the recognition of Elias as count of Maine in 1100, obtained for Fulk V the Young, his son by Bertrade de Montfort, the hand of Ermengarde, Elias's daughter and sole heiress.[5]In 1101 Gautier I count of Montsoreau gave the land to Robert of Arbrissel and Hersende of Champagne his mother in law to found the Abbey of Fontevraud.

Fulk V the Young (14 April 1109 – 1129) succeeded to the countship of Maine on the death of Elias (11 July 1110); but this increase of Angevin territory came into such direct collision with the interests of Henry I of England, who was also duke of Normandy, that a struggle between the two powers became inevitable. In 1112 it broke out, and Fulk, being unable to prevent Henry I from taking Alençon and making Robert, lord of Bellême, prisoner, was forced, at the treaty of Pierre Pecoulée, near Alençon (23 February 1113), to do homage to Henry for Maine. In revenge for this, while Louis VI was overrunning the Vexin in 1118, he routed Henry's army at Alençon (November), and in May 1119 Henry demanded a peace, which was sealed in June by the marriage of his eldest son, William the Aetheling, with Matilda, Fulk's daughter. William the Aetheling having perished in the wreck of the White Ship (25 November 1120), Fulk, on his return from a pilgrimage to the Holy Land (1120–1121), married his second daughter Sibyl, at the instigation of Louis VI, to William Clito, son of Robert Curthose, and a claimant to the duchy of Normandy, giving her Maine for a dowry (1122 or 1123). Henry I managed to have the marriage annulled, on the plea of kinship between the parties (1123 or 1124). But in 1127 a new alliance was made, and on 22 May at Rouen, Henry I betrothed his daughter Matilda, widow of the emperor Henry V, to Geoffrey the Handsome, son of Fulk, the marriage being celebrated at Le Mans on 2 June 1129. Shortly after, on the invitation of Baldwin II of Jerusalem, Fulk departed to the Holy Land for good, married Melisinda, Baldwin's daughter and heiress, and succeeded to the throne of Jerusalem (14 September 1131). His eldest son, Geoffrey V the Handsome or "Plantagenet", succeeded him as count of Anjou (1129 – 7 September 1151).[5]

The Plantagenets

From the outset, Geoffrey Plantagenet tried to profit by his marriage and, after the death of his father-in-law Henry I (1 December 1135), laid the foundation of the conquest of Normandy by a series of campaigns: about the end of 1135 or the beginning of 1136, he entered that country and rejoined his wife, the Empress Matilda, who had received the submission of Argentan, Domfront and Exmes. Having been abruptly recalled into Anjou by a revolt of his barons, he returned to the charge in September 1136 with a strong army, including in its ranks William, duke of Aquitaine, Geoffrey, count of Vendome, and William Talvas, count of Ponthieu. After a few successes he was wounded in the foot at the Siege of Le Sap (1 October) and had to fall back.[5]

May 1137 began a fresh campaign in which he devastated the district of Hiémois (near Exmes) and burnt Bazoches. In June 1138, with the aid of Robert of Gloucester, Geoffrey obtained the submission of Bayeux and Caen; in October he devastated the neighbourhood of Falaise; and finally, in March 1141, on hearing of his wife's success in England, he again entered Normandy, when he made a triumphal procession through the country. Town after town surrendered: in 1141, Verneuil, Nonancourt, Lisieux, Falaise; in 1142, Mortain, Saint-Hilaire, Pontorson; in 1143, Avranches, Saint-Lô, Cérences, Coutances, Cherbourg; in the beginning of 1144 he entered Rouen, and on 19 January received the ducal crown in its cathedral. Finally, in 1149, after crushing a last attempt at revolt, he handed over the duchy to his son Henry Curtmantle, who received the investiture at the hands of the king of France.[5]

All the while that Fulk the Younger and Geoffrey the Handsome were carrying on the work of extending the countship of Anjou, they did not neglect to strengthen their authority at home, to which the unruliness of the barons was a menace. As regards Fulk the Young, we know only a few isolated facts and dates: about 1109 Doué and L'Île Bouchard were taken; in 1112 Brissac was besieged, and about the same time Eschivard of Preuilly subdued. In 1114 there was a general war against the barons who were in revolt; and in 1118 a fresh rising, which was put down after the siege of Montbazon: in 1123 the lord of Doué revolted, and in 1124 Montreuil-Bellay was taken after a siege of nine weeks. Geoffrey the Handsome, with his indefatigable energy, was eminently fitted to suppress the coalitions of his vassals, the most formidable of which was formed in 1129. Among those who revolted were Guy IV of Laval, Giraud II of Montreuil-Bellay, the viscount of Thouars, the lords of Mirebeau, Amboise, Parthenay and Sablé. Geoffrey succeeded in beating them one after another, razed the keep of Thouars and occupied Mirebeau.[5]

Another rising was crushed in 1134 by the destruction of Cand and the taking of L'Île Bouchard. In 1136, while the count was in Normandy, Robert III of Sablé put himself at the head of the movement, to which Geoffrey responded by destroying Briollay and occupying La Suze; and Robert of Sablé himself was forced to beg humbly for pardon through the intercession of the bishop of Angers. In 1139 Geoffrey took Mirebeau, and in 1142 Champtoceaux, but in 1145 a new revolt broke out, this time under the leadership of Elias, the count's own brother, who, again with the assistance of Robert of Sablé, laid claim to the countship of Maine. Geoffrey took Elias prisoner, forced Robert of Sablé to beat a retreat, and reduced the other barons to reason. In 1147 he destroyed Doué and Blaison. Finally in 1150 he was checked by the revolt of Giraud, Lord of Montreuil-Bellay; for a year he besieged the place until it had to surrender, and he then took Giraud prisoner and only released him on the mediation of the king of France.[5]

Thus, on the death of Geoffrey the Handsome (7 September 1151), his son Henry found himself heir to a great empire, strong and consolidated, and to which his marriage with Eleanor of Aquitaine (May 1152) further added Aquitaine.[5]

At length on the death of King Stephen, Henry was recognised as King of England (19 December 1154), as agreed in the Treaty of Wallingford. But then his brother Geoffrey, Count of Nantes, who had received as appanage the three fortresses of Chinon, Loudun and Mirebeau, tried to seize upon Anjou, on the pretext that, by the will of their father, Geoffrey the Handsome, all the paternal inheritance ought to descend to him, if Henry succeeded in obtaining possession of the maternal inheritance. On hearing of this, Henry, although he had sworn to observe this will, had himself released from his oath by the pope, and hurriedly marched against his brother, from whom in the beginning of 1156 he succeeded in taking Chinon and Mirebeau; and in July he forced Geoffrey to give up even his three fortresses in return for an annual pension. Henceforward Henry succeeded in keeping the countship of Anjou all his life; for though he granted it in 1168 to his son Henry the Young King when the latter became old enough to govern it, he absolutely refused to allow him to enjoy his power. After Henry II's death in 1189 the countship, together with the rest of his dominions, passed to his son Richard I of England, but on the death of the latter in 1199, Arthur of Brittany (born in 1187) laid claim to the inheritance, which ought, according to him, to have fallen to his father Geoffrey, fourth son of Henry II, in accordance with the custom by which "the son of the eldest brother should succeed to his father's patrimony." He therefore set himself up in rivalry with John Lackland, youngest son of Henry II, and supported by Philip Augustus of France, and aided by William des Roches, seneschal of Anjou, he managed to enter Angers (18 April 1199) and there have himself recognized as count of the three countships of Anjou, Maine and Touraine, for which he did homage to the King of France. King John soon regained the upper hand, for Philip Augustus, having deserted Arthur by the Treaty of Le Goulet (22 May 1200), John made his way into Anjou; and on 18 June 1200 was recognized as count at Angers. In 1202 he refused to do homage to Philip Augustus, who, in consequence, confiscated all his continental possessions, including Anjou, which was allotted by the king of France to Arthur. The defeat of the latter, who was taken prisoner at Mirebeau on 1 August 1202, seemed to ensure John's success, but he was abandoned by William des Roches, who in 1203 assisted Philip Augustus in subduing the whole of Anjou. A last effort on the part of John to possess it himself in 1214, led to the taking of Angers (17 June), but broke down lamentably at the Battle of La Roche-aux-Moines (2 July), and the countship was attached to the crown of France.[5]

Shortly afterwards it was separated from it again, when in August 1246 King Louis IX gave it as an appanage to his brother Charles, Count of Provence, soon to become king of Naples and Sicily. Charles I of Anjou, engrossed with his other dominions, gave little thought to Anjou, nor did his son Charles II, the Lame, who succeeded him on 7 January 1285. On 16 August 1290, the latter married his daughter Margaret, Countess of Anjou to Charles of Valois, son of Philip III the Bold, giving her Anjou and Maine for dowry, in exchange for Charles of Valois's claims to the kingdoms of Aragon and Valentia and the countship of Barcelona. Charles of Valois at once entered into possession of the countship of Anjou, to which Philip IV, the Fair, in September 1297, attached a peerage of France. On 16 December 1325, Charles died, leaving Anjou to his eldest son Philip of Valois, on whose recognition as King of France (Philip VI) on 1 April 1328, the countship of Anjou was again united to the crown.[5]

French duchy

On 17 February 1332, Philip VI bestowed it on his son John the Good, who, when he became king in turn (22 August 1350), gave the countship to his second son Louis I, raising it to a duchy in the peerage of France by letters patent of 25 October 1360. Louis I, who became in time count of Provence and titular king of Naples, died in 1384, and was succeeded by his son Louis II, who devoted most of his energies to his Neapolitan ambitions, and left the administration of Anjou almost entirely in the hands of his wife, Yolande of Aragon. On his death (29 April 1417), she took upon herself the guardianship of their young son Louis III, and, in her capacity of regent, defended the duchy against the English. Louis III, who also devoted himself to winning Naples, died on 15 November 1434, leaving no children. The duchy of Anjou then passed to his brother René, second son of Louis II and Yolande of Aragon.[5]

Unlike his predecessors, who had rarely stayed long in Anjou, René from 1443 onwards paid long visits to it, and his court at Angers became one of the most brilliant in the kingdom of France. But after the sudden death of his son John in December 1470, René, for reasons which are not altogether clear, decided to move his residence to Provence and leave Anjou for good. After making an inventory of all his possessions, he left the duchy in October 1471, taking with him the most valuable of his treasures. On 22 July 1474 he drew up a will by which he divided the succession between his grandson René II of Lorraine and his nephew Charles II, count of Maine. On hearing this, King Louis XI, who was the son of one of King René's sisters, seeing that his expectations were thus completely frustrated, seized the duchy of Anjou. He did not keep it very long, but became reconciled to René in 1476 and restored it to him, on condition, probably, that René should bequeath it to him. However that may be, on the death of the latter (10 July 1480) he again added Anjou to the royal domain.[5]

Later, King Francis I again gave the duchy as an appanage to his mother, Louise of Savoy, by letters patent of 4 February 1515. On her death, in September 1531, the duchy returned into the king's possession. In 1552 it was given as an appanage by Henry II to his son Henry of Valois, who, on becoming king in 1574, with the title of Henry III, conceded it to his brother Francis, duke of Alençon, at the treaty of Beaulieu near Loches (6 May 1576). Francis died on 10 June 1584, and the vacant appanage definitively became part of the royal domain.[5]

At first Anjou was included in the gouvernement (or military command) of Orléanais, but in the 17th century was made into a separate one. Saumur, however, and the Saumurois, for which King Henry IV had in 1589 created an independent military governor-generalship in favour of Duplessis-Mornay, continued till the Revolution to form a separate gouvernement, which included, besides Anjou, portions of Poitou and Mirebalais. Attached to the généralité (administrative circumscription) of Tours, Anjou on the eve of the Revolution comprised five êlections (judicial districts):--Angers, Baugé, Saumur, Château-Gontier, Montreuil-Bellay and part of the êlections of La Flèche and Richelieu. Financially it formed part of the so-called pays de grande gabelle, and comprised sixteen special tribunals, or greniers à sel (salt warehouses):--Angers, Baugé, Beaufort, Bourgueil, Candé, Château-Gontier, Cholet, Craon, La Flèche, Saint-Florent-le-Vieil, Ingrandes, Le Lude, Pouancé, Saint-Rémy-la-Varenne, Richelieu, Saumur. From the point of view of purely judicial administration, Anjou was subject to the parlement of Paris; Angers was the seat of a presidial court, of which the jurisdiction comprised the sénéchaussées of Angers, Saumur, Beaugé, Beaufort and the duchy of Richelieu; there were besides presidial courts at Château-Gontier and La Flèche. When the Constituent Assembly, on 26 February 1790, decreed the division of France into départments, Anjou and the Saumurois, with the exception of certain territories, formed the départment of Maine-et-Loire, as at present constituted.[5]

Gallery

Notes

- "Anjou". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- "Anjou" (US) and {{Cite Oxford Dictionaries|Anjou|accessdate=11 May 2019}}

- "Anjou". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- Baynes 1878.

- Halphen 1911.

- Collins, p. 33.

References

- Collins, Paul, The Birth of the West: Rome, Germany, France, and the Creation of Europe in the Tenth Century.

Attribution:

Further reading

- The chronicles of Normandy by William of Poitiers and of Jumièges and Ordericus Vitalis (in Latin)

- The chronicles of Maine, particularly the Actus pontificum cenomannis in urbe degentium (in Latin)

- The Gesta consulum Andegavorum (in Latin)

- Chroniques des comtes d'Anjou, published by Marchegay and Salmon, with an introduction by E. Mabille, Paris, 1856–1871 (in French)

- Louis Halphen, Êtude sur les chroniques des comtes d'Anjou et des seigneurs d'Amboise (Paris, 1906) (in French)

- Louis Halphen, Recueil d'annales angevines et vendómoises (Paris, 1903) (in French)

- Auguste Molinier, Les Sources de l'histoire de France (Paris, 1902), ii. 1276–1310 (in French)

- Louis Halphen, Le Comté d'Anjou au XIe siècle (Paris, 1906) (in French)

- Kate Norgate, England under the Angevin Kings (2 vols., London, 1887)

- A. Lecoy de La Marche, Le Roi René (2 vols., Paris, 1875). (in French)

- Célestin Port, Dictionnaire historique, géographique et biographique de Maine-et-Loire (3 vols., Paris and Angers, 1874–1878) (in French)

- idem, Préliminaires. (in French)

- Edward Augustus Freeman, The History of the Norman Conquest of England, its Causes and its Results (2d vol.)

- Luc d'Achery, Spicilegium, sive Collectio veterum aliquot scriptorum qui in Galliae bibliothecis, maxime Benedictinorum, latuerunt (in Latin)