Mantis

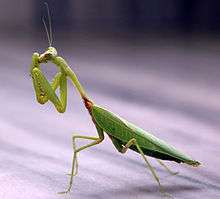

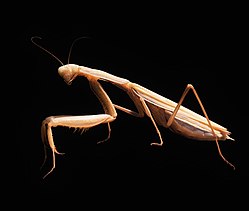

Mantises are an order (Mantodea) of insects that contains over 2,400 species in about 430 genera in 15 families. The largest family is the Mantidae ("mantids"). Mantises are distributed worldwide in temperate and tropical habitats. They have triangular heads with bulging eyes supported on flexible necks. Their elongated bodies may or may not have wings, but all Mantodea have forelegs that are greatly enlarged and adapted for catching and gripping prey; their upright posture, while remaining stationary with forearms folded, has led to the common name praying mantis.

| Mantis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Superorder: | Dictyoptera |

| Order: | Mantodea Burmeister, 1838 |

| Families | |

|

see text | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The closest relatives of mantises are the termites and cockroaches (Blattodea), which are all within the superorder Dictyoptera. Mantises are sometimes confused with stick insects (Phasmatodea), other elongated insects such as grasshoppers (Orthoptera), or other unrelated insects with raptorial forelegs such as mantisflies (Mantispidae). Mantises are mostly ambush predators, but a few ground-dwelling species are found actively pursuing their prey. They normally live for about a year. In cooler climates, the adults lay eggs in autumn, then die. The eggs are protected by their hard capsules and hatch in the spring. Females sometimes practice sexual cannibalism, eating their mates after copulation.

Mantises were considered to have supernatural powers by early civilizations, including Ancient Greece, Ancient Egypt, and Assyria. A cultural trope popular in cartoons imagines the female mantis as a femme fatale. Mantises are among the insects most commonly kept as pets.

Taxonomy and evolution

Over 2,400 species of mantis in about 430 genera are recognized.[1] They are predominantly found in tropical regions, but some live in temperate areas.[2][3] The systematics of mantises have long been disputed. Mantises, along with stick insects (Phasmatodea), were once placed in the order Orthoptera with the cockroaches (now Blattodea) and rock crawlers (now Grylloblattodea). Kristensen (1991) combined the Mantodea with the cockroaches and termites into the order Dictyoptera, suborder Mantodea.[4][5] The name mantodea is formed from the Ancient Greek words μάντις (mantis) meaning "prophet", and εἶδος (eidos) meaning "form" or "type". It was coined in 1838 by the German entomologist Hermann Burmeister.[6][7] The order is occasionally called the mantes, using a Latinized plural of Greek mantis. The name mantid properly refers only to members of the family Mantidae, which was, historically, the only family in the order. The other common name, praying mantis, applied to any species in the order[8] (though in Europe mainly to Mantis religiosa), comes from the typical "prayer-like" posture with folded forelimbs.[9][10] The vernacular plural "mantises" (used in this article) was confined largely to the US, with "mantids" predominantly used as the plural in the UK and elsewhere, until the family Mantidae was further split in 2002.[11][12]

One of the earliest classifications splitting an all-inclusive Mantidae into multiple families was that proposed by Beier in 1968, recognizing eight families,[13] though it was not until Ehrmann's reclassification into 15 families in 2002[12] that a multiple-family classification became universally adopted. Klass, in 1997, studied the external male genitalia and postulated that the families Chaeteessidae and Metallyticidae diverged from the other families at an early date.[14] However as previously configured, the Mantidae and Thespidae especially were considered polyphyletic,[15] so the Mantodea have been revised substantially.[16]

Extant Families

The Mantodea Species File[17] now places extant families in the suborder Eumantodea, which includes:

- superfamily CHAETEESSOIDEA

- Chaeteessidae: Neotropical

- infraorder Spinomantodea - superfamily MANTOIDOIDEA

- Mantoididae: Neotropical

superfamily group Amerimantodea

- superfamily ACANTHOPOIDEA

- Acanthopidae: Neotropical

- Acontistidae: Neotropical

- Angelidae: Central America

- Coptopterygidae: Neotropical

- Liturgusidae: Neotropical

- Photinaidae: Neotropical

- superfamily THESPOIDEA

- Thespidae: Neotropical

superfamily group Cernomantodea

- superfamily CHROICOPTEROIDEA

- Chroicopteridae: Africa, Indian Ocean

- superfamily EPAPHRODITOIDEA

- Epaphroditidae: Caribbean

- Majangidae: Madagascar

- superfamily EREMIAPHILOIDEA

- Amelidae: Africa, Asia, Europe and North America

- Eremiaphilidae: Egypt, Middle-East, temperate Asia

- Rivetinidae: Africa, southern Europe, Asia

- Toxoderidae: Africa and Asia

- superfamily GALINTHIADOIDEA

- Galinthiadidae: Sub-Saharan Africa

- superfamily GONYPETOIDEA

- Gonypetidae: NE Africa, Middle East, India, Indochina, Malesia to New Guinea

- superfamily HAANIOIDEA

- Haaniidae: Asia

- superfamily HOPLOCORYPHOIDEA

- Hoplocoryphidae: Africa

- superfamily HYMENOPOIDEA

- Empusidae: North Africa

- Hymenopodidae: Africa, India, China, Indo-China, Borneo, PNG (now includes the Sibyllidae)

- superfamily MANTOIDEA

- Dactylopterygidae: Africa

- Deroplatyidae: Africa, tropical Asia

- Mantidae: Worldwide

- superfamily MIOMANTOIDEA

- Miomantidae: Africa

- superfamily NANOMANTOIDEA

- Amorphoscelididae: Africa, Arabia, India through to New Guinea (PNG), Australia and Oceania

- Leptomantellidae: Asia, including India and Indochina

- Nanomantidae: Africa including Madagascar, Himalayas, SE Asia through to Australia and Pacific islands

Substantially Revised

- Iridopterygidae: obsolete, now mostly Nanomantidae and Gonypetidae

- Liturgusidae: now Neotropical tribes only

- Mantidae: Worldwide: reorganised and subfamilies removed

- Stenophyllidae: now in family Acanthopidae

- Tarachodidae: now obsolete

- Thespidae: now Neotropical tribes only

Fossil Mantids

The earliest mantis fossils are about 135 million years old, from Siberia.[15] Fossils of the group are rare: by 2007, only about 25 fossil species were known.[15] Fossil mantises, including one from Japan with spines on the front legs as in modern mantises, have been found in Cretaceous amber.[18] Most fossils in amber are nymphs; compression fossils (in rock) include adults. Fossil mantises from the Crato Formation in Brazil include the 10 mm (0.39 in) long Santanmantis axelrodi, described in 2003; as in modern mantises, the front legs were adapted for catching prey. Well-preserved specimens yield details as small as 5 μm through X-ray computed tomography.[15]

Parallel evolution

Because of the superficially similar raptorial forelegs, mantidflies may be confused with mantises, though they are unrelated. Their similarity is an example of convergent evolution; mantidflies do not have tegmina (leathery forewings) like mantises, their antennae are shorter and less thread-like, and the raptorial tibia is more muscular than that of a similar-sized mantis and bends back further in preparation for shooting out to grasp prey.[19]

Biology

Anatomy

Mantises have large, triangular heads with a beak-like snout and mandibles. They have two bulbous compound eyes, three small simple eyes, and a pair of antennae. The articulation of the neck is also remarkably flexible; some species of mantis can rotate their heads nearly 180°.[10] The mantis thorax consists of a prothorax, a mesothorax, and a metathorax. In all species apart from the genus Mantoida, the prothorax, which bears the head and forelegs, is much longer than the other two thoracic segments. The prothorax is also flexibly articulated, allowing for a wide range of movements of the head and fore limbs while the remainder of the body remains more or less immobile.[20][21] Mantids also are unique to the Dictyoptera in that they have tympanate hearing, with two tympana in an auditory chamber in their metathorax. Most mantids can only hear ultrasound. [22]

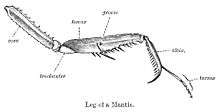

Mantises have two spiked, grasping forelegs ("raptorial legs") in which prey items are caught and held securely. In most insect legs, including the posterior four legs of a mantis, the coxa and trochanter combine as an inconspicuous base of the leg; in the raptorial legs, however, the coxa and trochanter combine to form a segment about as long as the femur, which is a spiky part of the grasping apparatus (see illustration). Located at the base of the femur is a set of discoidal spines, usually four in number, but ranging from none to as many as five depending on the species. These spines are preceded by a number of tooth-like tubercles, which, along with a similar series of tubercles along the tibia and the apical claw near its tip, give the foreleg of the mantis its grasp on its prey. The foreleg ends in a delicate tarsus used as a walking appendage, made of four or five segments and ending in a two-toed claw with no arolium.[20][23]

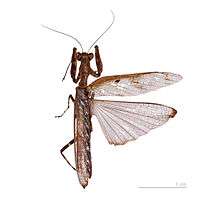

Mantises can be loosely categorized as being macropterous (long-winged), brachypterous (short-winged), micropterous (vestigial-winged), or apterous (wingless). If not wingless, a mantis has two sets of wings: the outer wings, or tegmina, are usually narrow and leathery. They function as camouflage and as a shield for the hind wings, which are clearer and more delicate.[20][24] The abdomen of all mantises consists of 10 tergites, with a corresponding set of nine sternites visible in males and seven visible in females. The abdomen tends to be slimmer in males than females, but ends in a pair of cerci in both sexes.[20]

Vision

Mantises have stereo vision.[25][26][27] They locate their prey by sight; their compound eyes contain up to 10,000 ommatidia. A small area at the front called the fovea has greater visual acuity than the rest of the eye, and can produce the high resolution necessary to examine potential prey. The peripheral ommatidia are concerned with perceiving motion; when a moving object is noticed, the head is rapidly rotated to bring the object into the visual field of the fovea. Further motions of the prey are then tracked by movements of the mantis's head so as to keep the image centered on the fovea.[23][28] The eyes are widely spaced and laterally situated, affording a wide binocular field of vision and precise stereoscopic vision at close range.[29] The dark spot on each eye that moves as it rotates its head is a pseudopupil. This occurs because the ommatidia that are viewed "head-on" absorb the incident light, while those to the side reflect it.[30]

As their hunting relies heavily on vision, mantises are primarily diurnal. Many species, however, fly at night, and then may be attracted to artificial lights. Mantises in the family Liturgusidae collected at night have been shown to be predominately males;[31] this is probably true for most mantises. Nocturnal flight is especially important to males in locating less-mobile females by detecting their pheromones. Flying at night exposes mantises to fewer bird predators than diurnal flight would. Many mantises also have an auditory thoracic organ that helps them avoid bats by detecting their echolocation calls and responding evasively.[32][33]

Diet and predation

_butterfly.jpg)

Mantises are generalist predators of arthropods.[2] The majority of mantises are ambush predators that only feed upon live prey within their reach. They either camouflage themselves and remain stationary, waiting for prey to approach, or stalk their prey with slow, stealthy movements.[34]

Larger mantises sometimes eat smaller individuals of their own species,[35] as well as small vertebrates such as lizards, frogs, fishes, and particularly small birds.[36][37][38][39]

Most mantises stalk tempting prey if it strays close enough, and will go further when they are especially hungry.[40] Once within reach, mantises strike rapidly to grasp the prey with their spiked raptorial forelegs.[41] Some ground and bark species pursue their prey in a more active way. For example, members of a few genera such as the ground mantises, Entella, Ligaria, and Ligariella run over dry ground seeking prey, much as tiger beetles do.[20]

The fore gut of some species extends the whole length of the insect and can be used to store prey for digestion later. This may be advantageous in an insect that feeds intermittently.[42] Chinese mantises live longer, grow faster, and produce more young when they are able to eat pollen.[43]

Antipredator adaptations

Mantises are preyed on by vertebrates such as frogs, lizards, and birds, and by invertebrates such as spiders, large species of hornets, and ants.[44] Some hunting wasps, such as some species of Tachytes also paralyse some species of mantis to feed their young.[45] Generally, mantises protect themselves by camouflage, most species being cryptically colored to resemble foliage or other backgrounds, both to avoid predators and to better snare their prey.[46] Those that live on uniformly colored surfaces such as bare earth or tree bark are dorsoventrally flattened so as to eliminate shadows that might reveal their presence.[47] The species from different families called flower mantises are aggressive mimics: they resemble flowers convincingly enough to attract prey that come to collect pollen and nectar.[48][49][50] Some species in Africa and Australia are able to turn black after a molt towards the end of the dry season; at this time of year, bush fires occur and this coloration enables them to blend in with the fire-ravaged landscape (fire melanism).[47]

When directly threatened, many mantis species stand tall and spread their forelegs, with their wings fanning out wide. The fanning of the wings makes the mantis seem larger and more threatening, with some species enhancing this effect with bright colors and patterns on their hind wings and inner surfaces of their front legs. If harassment persists, a mantis may strike with its forelegs and attempt to pinch or bite. As part of the bluffing (deimatic) threat display, some species may also produce a hissing sound by expelling air from the abdominal spiracles. Mantises lack chemical protection, so their displays are largely bluff. When flying at night, at least some mantises are able to detect the echolocation sounds produced by bats; when the frequency begins to increase rapidly, indicating an approaching bat, they stop flying horizontally and begin a descending spiral toward the safety of the ground, often preceded by an aerial loop or spin. If caught, they may slash captors with their raptorial legs.[47][51][52]

Mantises, like stick insects, show rocking behavior in which the insect makes rhythmic, repetitive side-to-side movements. Functions proposed for this behavior include the enhancement of crypsis by means of the resemblance to vegetation moving in the wind. However, the repetitive swaying movements may be most important in allowing the insects to discriminate objects from the background by their relative movement, a visual mechanism typical of animals with simpler sight systems. Rocking movements by these generally sedentary insects may replace flying or running as a source of relative motion of objects in the visual field.[53] As ants may be predators of mantises, genera such as Loxomantis, Orthodera, and Statilia, like many other arthropods, avoid attacking them. Exploiting this behavior, a variety of arthropods, including some early-instar mantises, mimic ants to evade their predators.[54]

Leaf mimicry: Choeradodis has leaf-like fore wings and a widened green thorax.

Leaf mimicry: Choeradodis has leaf-like fore wings and a widened green thorax.- Adult female Iris oratoria performs a bluffing threat display, rearing back with the forelegs and wings spread and mouth opened.

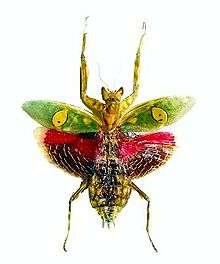

The jeweled flower mantis, Creobroter gemmatus: the brightly colored wings are opened suddenly in a deimatic display to startle predators.

The jeweled flower mantis, Creobroter gemmatus: the brightly colored wings are opened suddenly in a deimatic display to startle predators.

Reproduction and life history

The mating season in temperate climates typically takes place in autumn,[55][56] while in tropical areas, mating can occur at any time of the year.[56] To mate following courtship, the male usually leaps onto the female's back, clasping her thorax and wing bases with his forelegs. He then arches his abdomen to deposit and store sperm in a special chamber near the tip of the female's abdomen. The female lays between 10 and 400 eggs, depending on the species. Eggs are typically deposited in a froth mass-produced by glands in the abdomen. This froth hardens, creating a protective capsule, which together with the egg mass is called an ootheca. Depending on the species, the ootheca can be attached to a flat surface, wrapped around a plant, or even deposited in the ground.[55] Despite the versatility and durability of the eggs, they are often preyed on, especially by several species of parasitoid wasps. In a few species, mostly ground and bark mantises in the family Tarachodidae, the mother guards the eggs.[55] The cryptic Tarachodes maurus positions herself on bark with her abdomen covering her egg capsule, ambushing passing prey and moving very little until the eggs hatch.[4] An unusual reproductive strategy is adopted by Brunner's stick mantis from the southern United States; no males have ever been found in this species, and the females breed parthenogenetically.[2] The ability to reproduce by parthenogenesis has been recorded in at least two other species, Sphodromantis viridis and Miomantis sp., although these species usually reproduce sexually.[57][58][59] In temperate climates, adults do not survive the winter and the eggs undergo a diapause, hatching in the spring.[5]

As in closely related insect groups in the superorder Dictyoptera, mantises go through three life stages: egg, nymph, and adult (mantises are among the hemimetabolous insects). For smaller species, the eggs may hatch in 3–4 weeks as opposed to 4–6 weeks for larger species. The nymphs may be colored differently from the adult, and the early stages are often mimics of ants. A mantis nymph grows bigger as it molts its exoskeleton. Molting can happen five to 10 times before the adult stage is reached, depending on the species. After the final molt, most species have wings, though some species remain wingless or brachypterous ("short-winged"), particularly in the female sex. The lifespan of a mantis depends on the species; smaller ones may live 4–8 weeks, while larger species may live 4–6 months.[2][21]

- Mantis religiosa mating (brown male, green female)

Stagmomantis carolina laying ootheca

Stagmomantis carolina laying ootheca.jpg) Recently laid M. religiosa ootheca

Recently laid M. religiosa ootheca.jpg) Hatching from the ootheca

Hatching from the ootheca Sphodromantis lineola molting

Sphodromantis lineola molting

Sexual cannibalism

Sexual cannibalism is common among most predatory species of mantises in captivity. It has sometimes been observed in natural populations, where about a quarter of male-female encounters result in the male being eaten by the female.[60][61][62] Around 90% of the predatory species of mantises exhibit sexual cannibalism.[63] Adult males typically outnumber females at first, but their numbers may be fairly equivalent later in the adult stage,[5] possibly because females selectively eat the smaller males.[64] In Tenodera sinensis, 83% of males escape cannibalism after an encounter with a female, but since multiple matings occur, the probability of a male's being eaten increases cumulatively.[61]

The female may begin feeding by biting off the male's head (as they do with regular prey), and if mating has begun, the male's movements may become even more vigorous in its delivery of sperm. Early researchers thought that because copulatory movement is controlled by a ganglion in the abdomen, not the head, removal of the male's head was a reproductive strategy by females to enhance fertilization while obtaining sustenance. Later, this behavior appeared to be an artifact of intrusive laboratory observation. Whether the behavior is natural in the field or also the result of distractions caused by the human observer remains controversial. Mantises are highly visual organisms and notice any disturbance in the laboratory or field, such as bright lights or moving scientists. Chinese mantises that had been fed ad libitum (so that they were not hungry) actually displayed elaborate courtship behavior when left undisturbed. The male engages the female in a courtship dance, to change her interest from feeding to mating.[65] Under such circumstances, the female has been known to respond with a defensive deimatic display by flashing the colored eyespots on the inside of her front legs.[66]

The reason for sexual cannibalism has been debated; experiments show that females on poor diets are likelier to engage in sexual cannibalism than those on good diets.[67] Some hypothesize that submissive males gain a selective advantage by producing offspring; this is supported by a quantifiable increase in the duration of copulation among males which are cannibalized, in some cases doubling both the duration and the chance of fertilization. This is contrasted by a study where males were seen to approach hungry females with more caution, and were shown to remain mounted on hungry females for a longer time, indicating that males that actively avoid cannibalism may mate with multiple females. The same study also found that hungry females generally attracted fewer males than those that were well fed.[68] The act of dismounting after copulation is dangerous for males, for at this time, females most frequently cannibalize their mates. An increase in mounting duration appears to indicate that males wait for an opportune time to dismount a hungry female, who would be likely to cannibalize her mate.[66]

Relationship with humans

In literature and art

One of the earliest mantis references is in the ancient Chinese dictionary Erya, which gives its attributes in poetry, where it represents courage and fearlessness, and a brief description. A later text, the Jingshi Zhenglei Daguan Bencao ("Great History of Medical Material Annotated and Arranged by Types, Based upon the Classics and Historical Works") from 1108, gives accurate details of the construction of the egg packages, the development cycle, anatomy, and the function of the antennae. Although mantises are rarely mentioned in Ancient Greek sources, a female mantis in threat posture is accurately illustrated on a series of fifth-century BC silver coins, including didrachms, from Metapontum in Sicily.[69] In the 10th century AD, Byzantine era Adages, Suidas describes an insect resembling a slow-moving green locust with long front legs.[70] He translates Zenobius 2.94 with the words seriphos (maybe a mantis) and graus, an old woman, implying a thin, dried-up stick of a body.[71]

Western descriptions of the biology and morphology of the mantises became more accurate in the 18th century. Roesel von Rosenhof illustrated and described mantises and their cannibalistic behavior in the Insekten-Belustigungen (Insect Entertainments).[72]

_Photograph_By_Shantanu_Kuveskar.jpg)

Aldous Huxley made philosophical observations about the nature of death while two mantises mated in the sight of two characters in his 1962 novel Island (the species was Gongylus gongylodes). The naturalist Gerald Durrell's humorously autobiographical 1956 book My Family and Other Animals includes a four-page account of an almost evenly matched battle between a mantis and a gecko. Shortly before the fatal dénouement, Durrell narrates:

he [Geronimo the gecko] crashed into the mantis and made her reel, and grabbed the underside of her thorax in his jaws. Cicely [the mantis] retaliated by snapping both her front legs shut on Geronimo's hindlegs. They rustled and staggered across the ceiling and down the wall, each seeking to gain some advantage.[73]

M. C. Escher's woodcut Dream depicts a human-sized mantis standing on a sleeping bishop.[74] The 1957 film The Deadly Mantis features a mantis as a giant monster.

A cultural trope imagines the female mantis as a femme fatale. The idea is propagated in cartoons by Cable, Guy and Rodd, LeLievre, T. McCracken, and Mark Parisi, among others.[75][76][77][78] It ends Isabella Rossellini's short film about the life of a praying mantis in her 2008 Green Porno season for the Sundance Channel.[79][80]

Martial arts

Two martial arts separately developed in China have movements and fighting strategies based on those of the mantis.[81][82] As one of these arts was developed in northern China, and the other in southern parts of the country, the arts are today referred to (both in English and Chinese) as 'Northern Praying Mantis'[83] and 'Southern Praying Mantis'.[82] Both are very popular in China, and have also been exported to the West in recent decades.[82][83][84][85]

In mythology and religion

The mantis was revered by the southern African Khoi and San in whose cultures man and nature were intertwined; for its praying posture, the mantis was even named Hottentotsgot ("god of the Khoi") in the Afrikaans language that had developed among the first European settlers.[86] However, at least for the San, the mantis was only one of the manifestations of a trickster-deity who could assume many other forms, such as a snake, hare or vulture.[87] Several ancient civilizations did consider the insect to have supernatural powers; for the Greeks, it had the ability to show lost travelers the way home; in the Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead the "bird-fly" is a minor god that leads the souls of the dead to the underworld; in a list of 9th-century BC Nineveh grasshoppers (buru), the mantis is named necromancer (buru-enmeli) and soothsayer (buru-enmeli-ashaga).[72][88]

As pets

Mantises are among the insects most widely kept as pets.[89][90] Because the lifespan of a mantis is only about a year, people who want to keep mantises often breed them. In 2013 at least 31 species were kept and bred in the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and the United States.[91] In 1996 at least 50 species were known to be kept in captivity by members of the Mantis Study Group.[92] The Independent described the "giant Asian praying mantis" as "part stick insect with a touch of Buddhist monk",[93] and stated that they needed a vivarium around 30 cm (12 in) on each side.[93] The Daily South argued that a pet insect was no weirder than a pet rat or ferret, and that while a pet mantis was unusual, it would not "bark, shed, [or] need shots or a litter box".[94]

For pest control

Gardeners who prefer to avoid pesticides may encourage mantises in the hope of controlling insect pests.[95] However, mantises do not have key attributes of biological pest control agents; they do not specialize in a single pest insect, and do not multiply rapidly in response to an increase in such a prey species, but are general predators.[95] They eat whatever they can catch, including both harmful and beneficial insects.[94] They therefore have "negligible value" in biological control.[95]

Two species, the Chinese mantis and the European mantis, were deliberately introduced to North America in the hope that they would serve as pest controls for agriculture; they have spread widely in both the United States and Canada.[96]

Mantis-like robot

A prototype robot inspired by the forelegs of the praying mantis has front legs that allow the robot to walk, climb steps, and grasp objects. The multi-jointed leg provides dexterity via a rotatable joint. Future models may include a more spiked foreleg to improve the grip and ability to support more weight.[97]

References

- Otte, Daniel; Spearman, Lauren. "Mantodea Species File Online". Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- Hurd, I. E. (1999). "Ecology of Praying Mantids". In Prete, Fredrick R.; Wells, Harrington; Wells, Patrick H.; Hurd, Lawrence E. (eds.). The Praying Mantids. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 43–49. ISBN 978-0-8018-6174-1.

- Hurd, I. E. (1999). "Mantid in Ecological Research". In Prete, Fredrick R.; Wells, Harrington; Wells, Patrick H.; Hurd, Lawrence E. (eds.). The Praying Mantids. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 231. ISBN 978-0-8018-6174-1.

- Costa, James (2006). The Other Insect Societies. Harvard University Press. pp. 135–136. ISBN 978-0-674-02163-1.

- Capinera, John L. (2008). Encyclopedia of Entomology. 4. Springer. pp. 3033–3037. ISBN 978-1-4020-6242-1.

- Essig, Edward Oliver (1947). College entomology. Macmillan Company. pp. 124, 900. OCLC 809878.

- Harper, Douglas. "mantis". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Bullock, William (1812). A companion to the London Museum and Pantherion (12th ed.).

- Partington, Charles Frederick (1837). The British Cyclopædia of Natural History. 1. W. S. Orr.

- "Praying Mantis". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- Bragg, P. E. (1996). "Mantis, Mantid, Mantids, Mantises". Mantis Study Group Newsletter, 1:4.

- Ehrmann, R. 2002. Mantodea: Gottesanbeterinnen der Welt. Natur und Tier, Münster.

- Beier, M. (1968). "Ordnung Mantodea (Fangheuschrecken)". Handbuch der Zoologie. 4 (2): 3–12.

- Klass, Klaus-Dieter (1997). The external male genitalia and phylogeny of Blattaria and Mantodea. Zoologisches Forschungsinstitut. ISBN 978-3-925382-45-1.

- Martill, David M.; Bechly, Günter; Loveridge, Robert F. (2007). The Crato Fossil Beds of Brazil: Window into an Ancient World. Cambridge University Press. pp. 236–238. ISBN 978-1-139-46776-6.

- Schwarz CJ, Roy R (2019) The systematics of Mantodea revisited: an updated classification incorporating multiple data sources (Insecta: Dictyoptera) Annales de la Société entomologique de France (N.S.) International Journal of Entomology 55 [2: 101-196.]

- Mantodea Species File: order Mantodea (retrieved 10 July 2020)

- Ryall, Julian (25 April 2008). "Ancient Praying Mantis Found in Amber". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- Boyden, Thomas C. (1983). "Mimicry, predation and potential pollination by the mantispid, Climaciella brunnea var. instabilis (Say) (Mantispidae: Neuroptera)". Journal of the New York Entomological Society. 91 (4): 508–511. JSTOR 25009393.

- Roy, Roger (1999). "Morphology and Taxonomy". In Prete, Fredrick R.; Wells, Harrington; Wells, Patrick H.; Hurd, Lawrence E. (eds.). The Praying Mantids. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 21–33. ISBN 978-0-8018-6174-1.

- Siwanowicz, Igor (2009). Animals Up Close. Dorling Kindersley. pp. 38–39. ISBN -978-1-405-33731-1.

- Yager, David; Svenson, Gavin (1 July 2008). "Patterns of praying mantis auditory system evolution based on morphological, molecular, neurophysiological, and behavioural data". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. Oxford University Press. 94 (3): 541–568. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2008.00996.x. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- Corrette, Brian J. (1990). "Prey capture in the praying mantis Tenodera aridifolia sinensis: coordination of the capture sequence and strike movements" (PDF). Journal of Experimental Biology. 148: 147–180. PMID 2407798.

- Kemper, William T. "Insect Order ID: Mantodea (Praying Mantises, Mantids)" (PDF). Missouri Botanical Garden. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- Nityananda, Vivek; Tarawneh, Ghaith; Rosner, Ronny; Nicolas, Judith; Crichton, Stuart; Read, Jenny (2016). "Insect stereopsis demonstrated using a 3D insect cinema". Scientific Reports. 6: 18718. doi:10.1038/srep18718. PMC 4703989. PMID 26740144.

- Rossel, S (1983). "Binocular stereopsis in an insect". Nature. 302 (5911): 821–822. doi:10.1038/302821a0.

- Rossel, S (1996). "Binocular vision in insects: How mantids solve the correspondence problem". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 93 (23): 13229–13232. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.23.13229. PMC 24075. PMID 11038523.

- Simmons, Peter J.; Young, David (1999). Nerve Cells and Animal Behaviour. Cambridge University Press. p. 8990. ISBN 978-0-521-62726-9.

- Howard, Ian P.; Rogers, Brian J. (1995). Binocular Vision and Stereopsis. Oxford University Press. p. 646. ISBN 978-0-19-508476-4.

- Zeil, Jochen; Al-Mutairi, Maha M. (1996). "Variations in the optical properties of the compound eyes of Uca lactea annulipes" (PDF). The Journal of Experimental Biology. 199 (7): 1569–1577. PMID 9319471.

- Bragg, P.E. (2010). "A review of the Liturgusidae of Borneo (Insecta: Mantodea)". Sepilok Bulletin. 12: 21–36.

- Yager, David (1999). "Hearing". In Prete, Fredrick R.; Wells, Harrington; Wells, Patrick H.; Hurd, Lawrence E. (eds.). The Praying Mantids. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 101–103. ISBN 978-0-8018-6174-1.

- Grimaldi, David; Engel, Michael, S. (2005). Evolution of the Insects. Cambridge University Press. p. 257. ISBN 978-0-521-82149-0.

- Ross, Edward S. (February 1984). "Mantids – The Praying Predators". National Geographic. 165 (2): 268–280. ISSN 0027-9358. OCLC 643483454.

- Capinera, John L. (2008). Encyclopedia of Entomology. Springer. p. 1509. ISBN 978-1-4020-6242-1.

- Grimaldi, David; Engel, Michael S. (2005). Evolution of the Insects. Cambridge University Press. p. 254. ISBN 978-0-521-82149-0.

- Nyffeler, Martin; Maxwell, Michael R.; Remsen, J. V., Jr. (2017). "Bird predation by praying mantises: a global perspective". The Wilson Journal of Ornithology. 129 (2): 331–344. doi:10.1676/16-100.1.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Battison, Roberto; et al. (2018). "The fishing mantid: predation on fish as a new adaptive strategy for praying mantids (Insecta: Mantodea)". Journal of Orthoptera Research. 27 (2): 155–158. doi:10.3897/jor.27.28067.

- Valdez, Jose W. "Arthropods as vertebrate predators: A review of global patterns". Global Ecology and Biogeography. n/a (n/a). doi:10.1111/geb.13157. ISSN 1466-8238.

- Gelperin, Alan (July 1968). "Feeding behaviour of the praying mantis: a learned modification". Nature. 219 (5152): 399–400. doi:10.1038/219399a0.

- Prete, F. R.; Cleal, K. S. (1996). "The predatory strike of free ranging praying mantises, Sphodromantis lineola (Burmeister). I: Strikes in the mid-sagittal plane". Brain, Behavior and Evolution. 48 (4): 173–190. doi:10.1159/000113196. PMID 8886389.

- Capinera, John L. (2008). Encyclopedia of Entomology. Springer. p. 116. ISBN 978-1-4020-6242-1.

- Beckman, Noelle; Hurd, Lawrence E. (2003). "Pollen feeding and fitness in praying mantids: the vegetarian side of a tritrophic predator". Environmental Entomology. 32 (4): 881–885. doi:10.1603/0046-225X-32.4.881.

- Iyer, Geetha (13 August 2011). "Down to earth". Frontline Magazine. 28 (17).

- Jean-Henri Fabre (1921). More Hunting Wasps. Dodd, Mead.

- Gullan, P. J.; Cranston, P. S. (2010). The Insects: An Outline of Entomology (4th ed.). Wiley. p. 370. ISBN 978-1-118-84616-2.

- Edmunds, Malcolm; Brunner, Dani (1999). "Ethology of Defenses against Predators". In Prete, Fredrick R.; Wells, Harrington; Wells, Patrick H.; Hurd, Lawrence E. (eds.). The Praying Mantids. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 282–293. ISBN 978-0-8018-6174-1.

- Cott, Hugh (1940). Adaptive Coloration in Animals. Methuen. pp. 392–393.

- Annandale, Nelson (1900). "Observations on the habits and natural surroundings of insects made during the 'Skeat Expedition' to the Malay Peninsula, 1899–1900". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. 69: 862–865.

- O'Hanlon, James C.; Holwell, Gregory I.; Herberstein, Marie E. (2014). "Pollinator deception in the orchid mantis". The American Naturalist. 183 (1): 126–132. doi:10.1086/673858. PMID 24334741.

- Yager, D.; May, M. (1993). "Coming in on a wing and an ear". Natural History. 102 (1): 28–33.

- "Praying Mantis Uses Ultrasonic Hearing to Dodge Bats". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- O'Dea, J. D. (1991). "Eine zusatzliche oder alternative Funktion der 'kryptischen' Schaukelbewegung bei Gottesanbeterinnen und Stabschrecken (Mantodea, Phasmatodea)". Entomologische Zeitschrift. 101 (1–2): 25–27.

- Nelson, Ximena J.; Jackson, Robert R. (2006). "Innate aversion to ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) and ant mimics: experimental findings from mantises (Mantodea)". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 88 (1): 23–32. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8312.2006.00598.x.

- Ene, J. C. (1964). "The distribution and post-embryonic development of Tarachodes afzelli (Stal) (Mantodea : Eremiaphilidae)". Journal of Natural History. 7 (80): 493–511. doi:10.1080/00222936408651488.

- Michael, Maxwell. R. (1999). "Mating Behavior". In Prete, Fredrick R.; Wells, Harrington; Wells, Patrick H.; Hurd, Lawrence E. (eds.). The Praying Mantids. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-8018-6174-1.

- Bragg, P.E. (1987) A case of parthenogenesis in a mantis. Bulletin of the Amateur Entomologists' Society, 46 (356): 160.

- Bragg, P. E. (December 1989). "Parthenogenetic mantid named". Mantis Study Group. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- Dickie, S. (1996) Parthenogenesis in mantids. Mantis Study Group Newsletter, 1: 5.

- Lawrence, S. E. (1992). "Sexual cannibalism in the praying mantid, Mantis religiosa: a field study". Animal Behaviour. 43 (4): 569–583. doi:10.1016/S0003-3472(05)81017-6.

- Hurd, L. E.; Eisenberg, R. M.; Fagan, W. F.; Tilmon, K. J.; Snyder, W. E.; Vandersall, K. S.; Datz, S. G.; Welch, J. D. (1994). "Cannibalism reverses male-biased sex ratio in adult mantids: female strategy against food limitation?". Oikos. 69 (2): 193–198. doi:10.2307/3546137. JSTOR 3546137.

- Maxwell, Michael R. (1998). "Lifetime mating opportunities and male mating behaviour in sexually cannibalistic praying mantids". Animal Behaviour. 55 (4): 1011–1028. doi:10.1006/anbe.1997.0671.

- Wilder, Shawn M.; Rypstra, Ann L.; Elgar, Mark A. (2009). "The importance of ecological and phylogenetic conditions for the occurrence and frequency of sexual cannibalism". Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics. 40: 21–39. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.110308.120238.

- "Do Female Praying Mantises Always Eat the Males?". Entomology Today. 22 December 2013. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- Liske, E.; Davis, W. J. (1984). "Sexual behaviour of the Chinese praying mantis". Animal Behaviour. 32 (3): 916–918. doi:10.1016/S0003-3472(84)80170-0.

- Lelito, Jonathan P.; Brown, William D. (2006). "Complicity or conflict over sexual cannibalism? Male risk taking in the praying mantis Tenodera aridifolia sinensis". The American Naturalist. 168 (2): 263–269. doi:10.1086/505757. PMID 16874635.

- Liske, E.; Davis, W. J. (1987). "Courtship and mating behaviour of the Chinese praying mantis, Tenodera aridifolia sinenesis". Animal Behaviour. 35 (5): 1524–1537. doi:10.1016/s0003-3472(87)80024-6.

- Maxwell, Michael R.; Gallego, Kevin M.; Barry, Katherine L. (2010). "Effects of female feeding regime in a sexually cannibalistic mantid: fecundity, cannibalism, and male response in Stagmomantis limbata (Mantodea)". Ecological Entomology. 35 (6): 775–787. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2311.2010.01239.x.

- Bodson, Liliane (2014). Campbell, Gordon Lindsay (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Animals in Classical Thought and Life. Oxford University Press. pp. 557–558. ISBN 978-0-19-958942-5.

- "Entomomancy". Occultopedia. California Astrology Association. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- Erasmus, Desiderius; Fantazzi, Charles (1992). Adages: Iivii1 to Iiiiii100. University of Toronto Press. pp. 334–335. ISBN 978-0-8020-2831-0.

- Prete, Frederick R.; Wells, Harrington & Wells, Patrick H. (1999). "The Predatory Behavior of Mantids: Historical Attitudes and Contemporary Questions". In Prete, Fredrick R.; Wells, Harrington; Wells, Patrick H. & Hurd, Lawrence E. (eds.). The Praying Mantids. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 3–8. ISBN 978-0-8018-6174-1.

- Durrell, Gerald (2006) [1956]. My Family and Other Animals. Penguin Books. pp. 204–208. ISBN 978-0-14-193609-3.

- Emmer, Michele; Schattschneider, Doris (2007). M.C. Escher's Legacy: A Centennial Celebration. Springer. p. 66. ISBN 978-3-540-28849-7.

- Wade, Lisa (29 November 2010). "Shoddy Research and Cultural Tropes: The Praying Mantis". The Society Pages. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- "Praying Mantises Cartoons and Comics". CartoonStock. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- Parisi, Mark. "Praying Mantis Cartoons". Off the Mark. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- McCracken, T. "Praying Mantis Should Be Gay". McHumor Cartoons. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- Rossellini, Isabella (2008). "Green Porno". Sundance Channel. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- Rossellini, Isabella (2009). "Green Porno: a series of short films by Isabella Rossellini" (Press Kit). Sundance Channel. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- "History of Praying Mantis Kung Fu". Praying Mantis Kung Fu Academy. Archived from the original on 1 October 2015. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- Hagood, Roger D. (2012). 18 Buddha Hands: Southern Praying Mantis Kung Fu. Southern Mantis Press. ISBN 978-0-9857240-1-6.

- Funk, Jon. "Praying Mantis Kung Fu". Praying Mantis Kung Fu. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- Barnes, Bryan. "Northern Praying Mantis Kung Fu". Shantung Northern Praying Mantis Kung Fu. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- Orum, Pete. "Chow Gar". Southern Mantis Kung Fu. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- "Insek-kaleidoskoop: Die 'skynheilige' hottentotsgot". Mieliestronk.com. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- "Siyabona Africa: Kruger National Park: San". Siyabona Africa. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- "Mantid". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- "Pet bugs: Kentucky arthropods". University of Kentucky. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- Van Zomeren, Linda. "European Mantis". Keeping Insects. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- Breeding Reports: 1st July 2013–1st October 2013 (PDF). UK Mantis Forums Newsletter (Newsletter). UK Mantis Forums. October 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- Bragg, P.E. [editor] (1996) Species in culture. Mantis Study Group Newsletter, 1: 2–3.

- Buckley, Jamie (17 October 2009). "Pet of the week: The giant Asian praying mantis". The Independent. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- Bender, Steve (30 August 2015). "Pet Your Praying Mantis". The Daily South. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- Doutt, R. L. "The Praying Mantis (Leaflet 21019)" (PDF). University of California Division of Agricultural Sciences. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- "Praying and Chinese Mantises". New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- Cardona, Ramon; Touretzky, David. "Leg Design for a Praying Mantis Robot". Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence. Florida Artificial Intelligence Research Society. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Mantis. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Mantodea |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mantodea. |

- Mantis Study Group – Information on mantises, phylogenetics and evolution.

- Mantodea Species File