Archaeognatha

The Archaeognatha are an order of apterygotes, known by various common names such as jumping bristletails. Among extant insect taxa they are some of the most evolutionarily primitive; they appeared in the Middle Devonian period at about the same time as the arachnids. Specimens that closely resemble extant species have been found as both body and trace fossils (the latter including body imprints and trackways) in strata from the remainder of the Paleozoic Era and more recent periods.[2] For historical reasons an alternative name for the order is Microcoryphia.[3]

| Archaeognatha | |

|---|---|

| Rock bristletail | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Subclass: | Monocondylia Haeckel, 1866 |

| Order: | Archaeognatha Börner, 1904 |

| Families | |

Until the late 20th century the suborders Zygentoma and Archaeognatha comprised the order Thysanura; both orders possess three-pronged tails comprising two lateral cerci and a medial epiproct or appendix dorsalis. Of the three organs, the appendix dorsalis is considerably longer than the two cerci; in this the Archaeognatha differ from the Zygentoma, in which the three organs are subequal in length.[3] In the late 20th century, it was recognized that the order Thysanura was paraphyletic, thus the two suborders were each raised to the status of an independent monophyletic order, with Archaeognatha sister taxon to the Dicondylia, including the Zygentoma.[4]

The order Archaeognatha is cosmopolitan; it includes roughly 500 species in two families.[5] No species is currently evaluated as being at conservation risk.[6]

Description

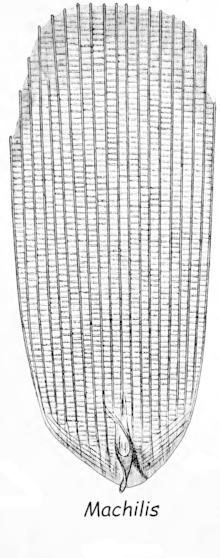

Archaeognatha are small insects with elongated bodies and backs that are arched, especially over the thorax. They have three long tail-like structures, of which the lateral two are cerci, while the medial filament, which is longest, is an epiproct. The antennae are flexible. The two large compound eyes meet at the top of the head, and there are three ocelli. The mouthparts are partly retractable, with simple chewing mandibles and long maxillary palps.[1]:341–343

Archaeognatha differ from Zygentoma in various ways, such as their relatively small head, their bodies being compressed laterally (from side to side) instead of flattened dorsiventrally, and in their being able to use their tails to spring up to 30 cm (12 in) into the air if disturbed. They also are unique among insects in possessing small, articulated "styli" on the hind (and sometimes middle) coxae and on sternites 2 to 9, which some authorities consider to be vestigial appendages. They have paired eversible membranous vesicles through which they absorb water.

.jpg)

Further unusual features are that the abdominal sternites are each composed of three sclerites, and they cement themselves to the substrate before molting. As in the Zygentoma, the body is covered with readily detached scales, that make the animals difficult to grip and also may protect the exoskeleton from abrasion. The thin exoskeleton offers little protection against dehydration. The animals accordingly must remain in moist air, such as in cool, damp situations under stones or bark.

Etymology

The name Archaeognatha is derived from Greek, ἀρχαῖος, (archaios) meaning ancient and γνάθος (gnathos) meaning "jaw". This refers to the articulation of the mandibles, which have a single phylogenetically primitive condyle each, where all more derived insects have two.

An alternative name, Microcoryphia,[3] comes from the Greek μικρός (mikros), meaning "small", and κορυφή (koryphē), which in context means "head".[7]

Taxonomy

| Families | No. of Species | Defining Notes | Image |

|---|---|---|---|

| Machilidae | 250 | Most are restricted to rocky shorelines | Need specific image |

| Meinertellidae | 20 | Lack scales at base of hind legs and antennae | Need specific image |

Biology

Archaeognatha occur in a wide range of habitats. While most species live in moist soil, others have adapted to chaparral, and even sandy deserts. They feed primarily on algae, but also lichens, mosses, or decaying organic detritus.

During courtship, the males spin a thread from the abdomen, attach one end to the substrate, and string packages of sperm (spermatophores) along it. After a series of courtship dances, the female picks up the spermatophores and places them on her ovipositor. She then lays a batch of around 30 eggs in a suitable crevice. The young resemble the adults, and take up to two years to reach sexual maturity, depending on the species and conditions such as temperature and available food.

Unlike most insects, the adults continue to moult after reaching adulthood, and typically mate once at each instar. Archaeognaths may have a total lifespan of up to four years, longer than most larger insects.[1]

References

- Howell V. Daly; John T. Doyen & Alexander H. Purcell (1998). Introduction to Insect Biology and Diversity (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-510033-6.

- Patrick R. Getty; Robert Sproule; David L. Wagner & Andrew M. Bush (2013). "Variation in wingless insect trace fossils: insights from neoichnology and the Pennsylvanian of Massachusetts". PALAIOS. 28: 243–258. doi:10.2110/palo.2012.p12-108r.

- Timothy J. Gibb (27 October 2014). Contemporary Insect Diagnostics: The Art and Science of Practical Entomology. Academic Press. pp. 78–. ISBN 978-0-12-404692-4.

- A. Blanke, M. Koch, B. Wipfler, F. Wilde, B. Misof (2014) Head morphology of Tricholepidion gertschi indicates monophyletic Zygentoma. Frontiers in Zoology 11:16 doi:10.1186/1742-9994-11-16

- The Royal Entomological Society Book of British Insects

- NC State University, ENT 425 | General Entomology | Resource Library | Compendium [Archeognatha]

- H. G. Liddell (1889). An Intermediate Greek-English Lexicon: Based on the 7th Ed of Liddell & Scott's Lexicon.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to Archaeognatha |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Archaeognatha. |

- Archaeognatha - Tree of Life Web Project

- Microcoryphia Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State College Department of Entomology