Mannerism

Mannerism, also known as Late Renaissance,[1][2] is a style in European art that emerged in the later years of the Italian High Renaissance around 1520, spreading by about 1530 and lasting until about the end of the 16th century in Italy, when the Baroque style largely replaced it. Northern Mannerism continued into the early 17th century.[3]

Stylistically, Mannerism encompasses a variety of approaches influenced by, and reacting to, the harmonious ideals associated with artists such as Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, and early Michelangelo. Where High Renaissance art emphasizes proportion, balance, and ideal beauty, Mannerism exaggerates such qualities, often resulting in compositions that are asymmetrical or unnaturally elegant.[4] The style is notable for its intellectual sophistication as well as its artificial (as opposed to naturalistic) qualities.[5] This artistic style privileges compositional tension and instability rather than the balance and clarity of earlier Renaissance painting. Mannerism in literature and music is notable for its highly florid style and intellectual sophistication.[6]

The definition of Mannerism and the phases within it continues to be a subject of debate among art historians. For example, some scholars have applied the label to certain early modern forms of literature (especially poetry) and music of the 16th and 17th centuries. The term is also used to refer to some late Gothic painters working in northern Europe from about 1500 to 1530, especially the Antwerp Mannerists—a group unrelated to the Italian movement. Mannerism has also been applied by analogy to the Silver Age of Latin literature.[7]

Nomenclature

The word, "Mannerism" derives from the Italian maniera, meaning "style" or "manner". Like the English word "style", maniera can either indicate a specific type of style (a beautiful style, an abrasive style) or indicate an absolute that needs no qualification (someone "has style").[8] In the second edition of his Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (1568), Giorgio Vasari used maniera in three different contexts: to discuss an artist's manner or method of working; to describe a personal or group style, such as the term maniera greca to refer to the Byzantine style or simply to the maniera of Michelangelo; and to affirm a positive judgment of artistic quality.[9] Vasari was also a Mannerist artist, and he described the period in which he worked as "la maniera moderna", or the "modern style".[10] James V. Mirollo describes how "bella maniera" poets attempted to surpass in virtuosity the sonnets of Petrarch.[11] This notion of "bella maniera" suggests that artists who were thus inspired looked to copying and bettering their predecessors, rather than confronting nature directly. In essence, "bella maniera" utilized the best from a number of source materials, synthesizing it into something new.[11]

As a stylistic label, "Mannerism" is not easily defined. It was used by Swiss historian Jacob Burckhardt and popularized by German art historians in the early 20th century to categorize the seemingly uncategorizable art of the Italian 16th century – art that was no longer found to exhibit the harmonious and rational approaches associated with the High Renaissance. "High Renaissance" connoted a period distinguished by harmony, grandeur and the revival of classical antiquity. The term "Mannerist" was redefined in 1967 by John Shearman[12] following the exhibition of Mannerist paintings organised by Fritz Grossmann at Manchester City Art Gallery in 1965.[13] The label "Mannerism" was used during the 16th century to comment on social behaviour and to convey a refined virtuoso quality or to signify a certain technique. However, for later writers, such as the 17th-century Gian Pietro Bellori, la maniera was a derogatory term for the perceived decline of art after Raphael, especially in the 1530s and 1540s.[14] From the late 19th century on, art historians have commonly used the term to describe art that follows Renaissance classicism and precedes the Baroque.

Yet historians differ as to whether Mannerism is a style, a movement, or a period; and while the term remains controversial it is still commonly used to identify European art and culture of the 16th century.[15]

Origin and development

By the end of the High Renaissance, young artists experienced a crisis:[4] it seemed that everything that could be achieved was already achieved. No more difficulties, technical or otherwise, remained to be solved. The detailed knowledge of anatomy, light, physiognomy and the way in which humans register emotion in expression and gesture, the innovative use of the human form in figurative composition, the use of the subtle gradation of tone, all had reached near perfection. The young artists needed to find a new goal, and they sought new approaches.[16] At this point Mannerism started to emerge.[4] The new style developed between 1510 and 1520 either in Florence,[17] or in Rome, or in both cities simultaneously.[18]

Origins and role models

This period has been described as a "natural extension"[6] of the art of Andrea del Sarto, Michelangelo, and Raphael. Michelangelo developed his own style at an early age, a deeply original one which was greatly admired at first, then often copied and imitated by other artists of the era.[6] One of the qualities most admired by his contemporaries was his terribilità, a sense of awe-inspiring grandeur, and subsequent artists attempted to imitate it.[6] Other artists learned Michelangelo's impassioned and highly personal style by copying the works of the master, a standard way that students learned to paint and sculpt. His Sistine Chapel ceiling provided examples for them to follow, in particular his representation of collected figures often called ignudi and of the Libyan Sibyl, his vestibule to the Laurentian Library, the figures on his Medici tombs, and above all his Last Judgment. The later Michelangelo was one of the great role models of Mannerism.[6] Young artists broke into his house and stole drawings from him.[19] In his book Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, Giorgio Vasari noted that Michelangelo stated once: "Those who are followers can never pass by whom they follow".[19]

The competitive spirit

The competitive spirit was cultivated by patrons who encouraged sponsored artists to emphasize virtuosic technique and to compete with one another for commissions. It drove artists to look for new approaches and dramatically illuminated scenes, elaborate clothes and compositions, elongated proportions, highly stylized poses, and a lack of clear perspective. Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo were each given a commission by Gonfaloniere Piero Soderini to decorate a wall in the Hall of Five Hundred in Florence. These two artists were set to paint side by side and compete against each other, fueling the incentive to be as innovative as possible.

Copy after lost original, Michelangelo's Battaglia di Cascina, by Bastiano da Sangallo, originally intended by Michelangelo to compete with Leonardo's entry for the same commission |

Copy after lost original, Leonardo da Vinci's Battaglia di Anghiari, by Rubens, originally intended by Leonardo to compete with Michelangelo's entry for the same commission |

Early mannerism

The early Mannerists in Florence—especially the students of Andrea del Sarto such as Jacopo da Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino who are notable for elongated forms, precariously balanced poses, a collapsed perspective, irrational settings, and theatrical lighting. Parmigianino (a student of Correggio) and Giulio Romano (Raphael's head assistant) were moving in similarly stylized aesthetic directions in Rome. These artists had matured under the influence of the High Renaissance, and their style has been characterized as a reaction to or exaggerated extension of it. Instead of studying nature directly, younger artists began studying Hellenistic sculpture and paintings of masters past. Therefore, this style is often identified as "anti-classical",[20] yet at the time it was considered a natural progression from the High Renaissance. The earliest experimental phase of Mannerism, known for its "anti-classical" forms, lasted until about 1540 or 1550.[18] Marcia B. Hall, professor of art history at Temple University, notes in her book After Raphael that Raphael's premature death marked the beginning of Mannerism in Rome.

In past analyses, it has been noted that mannerism arose in the early 16th century contemporaneously with a number of other social, scientific, religious and political movements such as the Copernican heliocentrism, the Sack of Rome in 1527, and the Protestant Reformation's increasing challenge to the power of the Catholic Church. Because of this, the style's elongated forms and distorted forms were once interpreted as a reaction to the idealized compositions prevalent in High Renaissance art.[21] This explanation for the radical stylistic shift c. 1520 has fallen out of scholarly favor, though early Mannerist art is still sharply contrasted with High Renaissance conventions; the accessibility and balance achieved by Raphael's School of Athens no longer seemed to interest young artists.

High maniera

The second period of Mannerism is commonly differentiated from the earlier, so-called "anti-classical" phase. Subsequent mannerists stressed intellectual conceits and artistic virtuosity, features that have led later critics to accuse them of working in an unnatural and affected "manner" (maniera). Maniera artists looked to their older contemporary Michelangelo as their principal model; theirs was an art imitating art, rather than an art imitating nature. Art historian Sydney Joseph Freedberg argues that the intellectualizing aspect of maniera art involves expecting its audience to notice and appreciate this visual reference—a familiar figure in an unfamiliar setting enclosed between "unseen, but felt, quotation marks".[22] The height of artifice is the Maniera painter's penchant for deliberately misappropriating a quotation. Agnolo Bronzino and Giorgio Vasari exemplify this strain of Maniera that lasted from about 1530 to 1580. Based largely at courts and in intellectual circles around Europe, Maniera art couples exaggerated elegance with exquisite attention to surface and detail: porcelain-skinned figures recline in an even, tempered light, acknowledging the viewer with a cool glance, if they make eye contact at all. The Maniera subject rarely displays much emotion, and for this reason works exemplifying this trend are often called 'cold' or 'aloof.' This is typical of the so-called "stylish style" or Maniera in its maturity.[23]

Spread of Mannerism

The cities Rome, Florence, and Mantua were Mannerist centers in Italy. Venetian painting pursued a different course, represented by Titian in his long career. A number of the earliest Mannerist artists who had been working in Rome during the 1520s fled the city after the Sack of Rome in 1527. As they spread out across the continent in search of employment, their style was disseminated throughout Italy and Northern Europe.[24] The result was the first international artistic style since the Gothic.[25] Other parts of Northern Europe did not have the advantage of such direct contact with Italian artists, but the Mannerist style made its presence felt through prints and illustrated books. European rulers, among others, purchased Italian works, while northern European artists continued to travel to Italy, helping to spread the Mannerist style. Individual Italian artists working in the North gave birth to a movement known as the Northern Mannerism. Francis I of France, for example, was presented with Bronzino's Venus, Cupid, Folly and Time. The style waned in Italy after 1580, as a new generation of artists, including the Carracci brothers, Caravaggio and Cigoli, revived naturalism. Walter Friedlaender identified this period as "anti-mannerism", just as the early Mannerists were "anti-classical" in their reaction away from the aesthetic values of the High Renaissance[26] and today the Carracci brothers and Caravaggio are agreed to have begun the transition to Baroque-style painting which was dominant by 1600.

Outside of Italy, however, Mannerism continued into the 17th century. In France, where Rosso traveled to work for the court at Fontainebleau, it is known as the "Henry II style" and had a particular impact on architecture. Other important continental centers of Northern Mannerism include the court of Rudolf II in Prague, as well as Haarlem and Antwerp. Mannerism as a stylistic category is less frequently applied to English visual and decorative arts, where native labels such as "Elizabethan" and "Jacobean" are more commonly applied. Seventeenth-century Artisan Mannerism is one exception, applied to architecture that relies on pattern books rather than on existing precedents in Continental Europe.[27]

Of particular note is the Flemish influence at Fontainebleau that combined the eroticism of the French style with an early version of the vanitas tradition that would dominate seventeenth-century Dutch and Flemish painting. Prevalent at this time was the pittore vago, a description of painters from the north who entered the workshops in France and Italy to create a truly international style.

Sculpture

As in painting, early Italian Mannerist sculpture was very largely an attempt to find an original style that would top the achievement of the High Renaissance, which in sculpture essentially meant Michelangelo, and much of the struggle to achieve this was played out in commissions to fill other places in the Piazza della Signoria in Florence, next to Michelangelo's David. Baccio Bandinelli took over the project of Hercules and Cacus from the master himself, but it was little more popular then than it is now, and maliciously compared by Benvenuto Cellini to "a sack of melons", though it had a long-lasting effect in apparently introducing relief panels on the pedestal of statues. Like other works of his and other Mannerists, it removes far more of the original block than Michelangelo would have done.[28] Cellini's bronze Perseus with the head of Medusa is certainly a masterpiece, designed with eight angles of view, another Mannerist characteristic, and artificially stylized in comparison with the Davids of Michelangelo and Donatello.[29] Originally a goldsmith, his famous gold and enamel Salt Cellar (1543) was his first sculpture, and shows his talent at its best.[30]

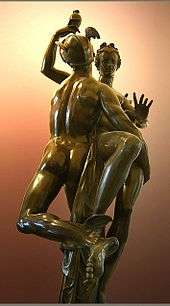

Small bronze figures for collector's cabinets, often mythological subjects with nudes, were a popular Renaissance form at which Giambologna, originally Flemish but based in Florence, excelled in the later part of the century. He also created life-size sculptures, of which two entered the collection in the Piazza della Signoria. He and his followers devised elegant elongated examples of the figura serpentinata, often of two intertwined figures, that were interesting from all angles.[31]

Stucco overdoor at Fontainebleau, probably designed by Primaticcio, who painted the oval inset, 1530s or 1540s

Stucco overdoor at Fontainebleau, probably designed by Primaticcio, who painted the oval inset, 1530s or 1540s Benvenuto Cellini, Perseus with the head of Medusa, 1545–1554

Benvenuto Cellini, Perseus with the head of Medusa, 1545–1554 Giambologna, Samson Slaying a Philistine, about 1562

Giambologna, Samson Slaying a Philistine, about 1562 Giambologna, Rape of the Sabine Women, 1583, Florence, Italy, 13' 6" high, marble

Giambologna, Rape of the Sabine Women, 1583, Florence, Italy, 13' 6" high, marble Adriaen de Vries, Mercury and Psyche Northern Mannerist life-size bronze, made in 1593 for Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emperor.

Adriaen de Vries, Mercury and Psyche Northern Mannerist life-size bronze, made in 1593 for Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emperor. Venus, c. 125; Marble, Roman; British Museum

Venus, c. 125; Marble, Roman; British Museum

Early theorists

Giorgio Vasari

Giorgio Vasari's opinions about the art of painting emerge in the praise he bestows on fellow artists in his multi-volume Lives of the Artists: he believed that excellence in painting demanded refinement, richness of invention (invenzione), expressed through virtuoso technique (maniera), and wit and study that appeared in the finished work, all criteria that emphasized the artist's intellect and the patron's sensibility. The artist was now no longer just a trained member of a local Guild of St Luke. Now he took his place at court alongside scholars, poets, and humanists, in a climate that fostered an appreciation for elegance and complexity. The coat-of-arms of Vasari's Medici patrons appears at the top of his portrait, quite as if it were the artist's own. The framing of the woodcut image of Vasari's Lives of the Artists would be called "Jacobean" in an English-speaking milieu. In it, Michelangelo's Medici tombs inspire the anti-architectural "architectural" features at the top, the papery pierced frame, the satyr nudes at the base. As a mere frame it is extravagant: Mannerist, in short.

Gian Paolo Lomazzo

Another literary figure from the period is Gian Paolo Lomazzo, who produced two works—one practical and one metaphysical—that helped define the Mannerist artist's self-conscious relation to his art. His Trattato dell'arte della pittura, scoltura et architettura (Milan, 1584) is in part a guide to contemporary concepts of decorum, which the Renaissance inherited in part from Antiquity but Mannerism elaborated upon. Lomazzo's systematic codification of aesthetics, which typifies the more formalized and academic approaches typical of the later 16th century, emphasized a consonance between the functions of interiors and the kinds of painted and sculpted decors that would be suitable. Iconography, often convoluted and abstruse, is a more prominent element in the Mannerist styles. His less practical and more metaphysical Idea del tempio della pittura (The ideal temple of painting, Milan, 1590) offers a description along the lines of the "four temperaments" theory of human nature and personality, defining the role of individuality in judgment and artistic invention.

Characteristics of artworks created during the Mannerist period

Mannerism was an anti-classical movement which differed greatly from the aesthetic ideologies of the Renaissance.[32] Though Mannerism was initially accepted with positivity based on the writings of Vasari,[32] it was later regarded in a negative light because it solely view as, "an alteration of natural truth and a trite repetition of natural formulas."[32] As an artistic moment, Mannerism involves many characteristics that are unique and specific to experimentation of how art is perceived. Below is a list of many specific characteristics that Mannerist artists would employ in their artworks.

- Elongation of figures: often Mannerist work featured the elongation of the human figure – occasionally this contributed to the bizarre imagery of some Mannerist art.[33]

- Distortion of perspective: in paintings, the distortion of perspective explored the ideals for creating a perfect space. However, the idea of perfection sometimes alluded to the creation of unique imagery. One way in which distortion was explored was through the technique of foreshortening. At times, when extreme distortion was utilized, it would render the image nearly impossible to decipher.[33]

- Black backgrounds: Mannerist artists often utilized flat black backgrounds to present a full contrast of contours in order to create dramatic scenes. Black backgrounds also contributed to a creating sense of fantasy within the subject matter.[33]

- Use of darkness and light: many Mannerists were interested in capturing the essence of the night sky through the use of intentional illumination, often creating a sense of fanatical scenes. Notably, special attention was paid to torch and moonlight to create dramatic scenes.[33]

- Sculptural forms: Mannerism was greatly influenced by sculpture, which gained popularity in the sixteenth century. As a result, Mannerist artists often based their depictions of human bodies in reference to sculptures and prints. This allowed Mannerist artists to focus on creating dimension.[33]

- Clarity of line: the attention that was paid to clean outlines of figures was prominent within Mannerism and differed largely from the Baroque and High Renaissance.The outlines of figures often allowed for more attention to detail.[33]

- Composition and space: Mannerist artists rejected the ideals of the Renaissance, notably the technique of one-point perspective. Instead, there was an emphasis on atmospheric effects and distortion of perspective. The use of space in Mannerist works instead privileged crowded compositions with various forms and figures or scant compositions with emphasis on black backgrounds.[33]

- Mannerist movement: the interest in the study of human movement often lead to Mannerist artists rendering a unique type of movement linked to serpentine positions. These positions often anticipate the movements of future positions because of their often-unstable motions figures. In addition, this technique attributes to the artist's experimentation of form.[33]

- Painted frames: in some Mannerist works, painted frames were utilized to blend in with the background of paintings and at times, contribute to the overall composition of the artwork. This is at times prevalent when there is special attention paid to ornate detailing.[33]

- Atmospheric effects: many Mannerists utilized the technique of sfumato, known as, "the rendering of soft and hazy contours or surfaces"[33] in their paintings for rendering the streaming of light.[33]

- Mannerist colour: a unique aspect of Mannerism was in addition to the experimentation of form, composition, and light, much of the same curiosity was applied to color. Many artworks toyed with pure and intense hues of blues, green, pinks, and yellows, which at times detract from the overall design of artworks, and at other times, compliment it. Additionally, when rending skin tone, artists would often concentrate on create overly creaming and light complexions and often utilize undertones of blue.[33]

Mannerist artists and examples of their works

Jacopo da Pontormo

Jacopo da Pontormo's work has been known as some of the most important contributions to Mannerism.[34] Much of his subject matter drew upon religious narratives as well as the influence of the works of Michelangelo[34] and referencing sculpture for composing human forms.[32] A well-known element of his work is the rendering of gazes by various figures which often pierce out at the viewer in various directions.[32] Dedicated to his work, Pontormo, often expressed anxiety about the quality of his work and was known to work slow and methodically.[32] His legacy is highly regarded, as he influenced artists such as Agnolo Bronzino and the aesthetic ideals of late Mannerism.[34]

Pontomoro's Joseph in Egypt, painted in 1517,[32] portrays a running narrative of four Biblical scenes in which Joseph reconnects with his family. On the left side of the composition, Pontomoro depicts a scene of Joseph introducing his family to the Pharaoh of Egypt. On the right, Joseph is riding on a rolling bench, as cherubs fill the composition around him in addition to other figures and large rocks on a path in the distance. Above these scenes, is a spiral staircase which Joseph guides one his sons to their mother at the top. The final scene, on the right, is the final stage of Jacob's death as his sons watch nearby.[32]

Pontormo's Joseph in Egypt features many Mannerist elements. One element is utilization of incongruous colors such as various shades of pinks and blues which make up a majority of the canvas. An additional element of Mannerism is the incoherent handling of time about the story of Joseph through various scenes and use of space. Through the inclusion of the four different narratives, Ponotormo creates a cluttered composition and overall sense of busyness.

Rosso Fiorentino and the School of Fontainebleau

Rosso Fiorentino, who had been a fellow pupil of Pontormo in the studio of Andrea del Sarto, in 1530 brought Florentine Mannerism to Fontainebleau, where he became one of the founders of French 16th-century Mannerism, popularly known as the School of Fontainebleau.

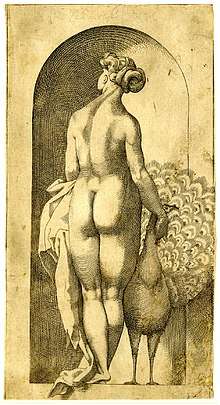

The examples of a rich and hectic decorative style at Fontainebleau further disseminated the Italian style through the medium of engravings to Antwerp, and from there throughout Northern Europe, from London to Poland. Mannerist design was extended to luxury goods like silver and carved furniture. A sense of tense, controlled emotion expressed in elaborate symbolism and allegory, and an ideal of female beauty characterized by elongated proportions are features of this style.

Agnolo Bronzino

Agnolo Bronzino was a pupil of Pontormo,[35] whose style was very influential and often confusing in terms of figuring out the attribution of many artworks.[35] During his career, Bronzino also collaborated with Vasari as a set designer for the production "Comedy of Magicians", where he painted many portraits.[35] Bronzino's work was sought after, and he enjoyed great success when he became a court painter for the Medici family in 1539.[35] A unique Mannerist characteristic of Bronzino's work was the rendering of milky complexions.[35]

In the painting, Venus, Cupid, Folly and Time, Bronzino portrays an erotic scene that leaves the viewer with more questions than answers. In the foreground, Cupid and Venus are nearly engaged in a kiss, but pause as if caught in the act. Above the pair are mythological figures, Father Time on the right, who pulls a curtain to reveal the pair and the representation of the goddess of the night on the left. The composition also involves a grouping of masks, a hybrid creature composed of features of a girl and a serpent, and a man depicted in agonizing pain. Many theories are available for the painting, such as it conveying the dangers of syphilis, or that the painting functioned as a court game.[36]

Mannerist portraits by Bronzino are distinguished by a serene elegance and meticulous attention to detail. As a result, Bronzino's sitters have been said to project an aloofness and marked emotional distance from the viewer. There is also a virtuosic concentration on capturing the precise pattern and sheen of rich textiles. Specifically, within the Venus, Cupid, Folly and Time, Bronzino utilizes the tactics of Mannerist movement, attention to detail, color, and sculptural forms. Evidence of Mannerist movement is apparent in the awkward movements of Cupid and Venus, as they contort their bodies to partly embrace. Particularly, Bronzino paints the complexion with the many forms as a perfect porcelain white with a smooth effacement of their muscles which provides a reference to the smoothness of sculpture.

Alessandro Allori

Alessandro Allori's (1535–1607) Susanna and the Elders (below) is distinguished by latent eroticism and consciously brilliant still life detail, in a crowded, contorted composition.

Jacopo Tintoretto

Jacopo Tintoretto has been known for his vastly different contributions to Venetian painting after the legacy of Titian. His work, which differed greatly from his predecessors, had been criticized by Vasari for its, "fantastical, extravagant, bizarre style."[37] Within his work, Tinitoretto adopted Mannerist elements that have distanced him from the classical notion of Venetian painting, as he often created artworks which contained elements of fantasy and retained naturalism.[37] Other unique elements of Tintoretto's work include his attention to color through the regular utilization of rough brushstrokes[37] and experimentation with pigment to create illusion.[37]

An artwork that is associated with Mannerist characteristics is the Last Supper; it was commissioned by Michele Alabardi for the San Giorgio Maggiore in 1591.[37] In Tintoretto's Last Supper, the scene is portrayed from the angle of group of people along the right side of the composition. On the left side of the painting, Christ and the Apostles occupy one side of the table and single out Judas. Within the dark space, there are few sources of light; one source is emitted by Christ's halo and hanging torch above the table.

In its distinct composition, the Last Supper portrays Mannerist characteristics. One characteristic that Tintoretto utilizes is a black background. Though the painting gives some indication of an interior space through the use of perspective, the edges of the composition are mostly shrouded in shadow which provides drama for the central scene of the Last Supper. Additionally, Tintoretto utilizes the spotlight effects with light, especially with the halo of Christ and the hanging torch above the table. A third Mannerist characteristic that Tintoretto employs are the atmospheric effects of figures shaped in smoke and float about the composition.

El Greco

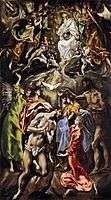

El Greco attempted to express religious emotion with exaggerated traits. After the realistic depiction of the human form and the mastery of perspective achieved in High Renaissance, some artists started to deliberately distort proportions in disjointed, irrational space for emotional and artistic effect. El Greco still is a deeply original artist. He has been characterized by modern scholars as an artist so individual that he belongs to no conventional school.[6] Key aspects of Mannerism in El Greco include the jarring "acid" palette, elongated and tortured anatomy, irrational perspective and light, and obscure and troubling iconography.[38][39] El Greco's style was a culmination of unique developments based on his Greek heritage and travels to Spain and Italy.[40]

El Greco's work reflects a multitude of styles including Byzantine elements as well as the influence of Caravaggio and Parmigianino in addition to Venetian coloring.[40] An important element is his attention to color as he regarded it to be one of the most important aspects of his painting.[41] Over the course of his career, El Greco's work remained in high demand as he completed important commissions in locations such as the Colegio de la Encarnación de Madrid.[40]

_-_Laoco%C3%B6n_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

El Greco's unique painting style and connection to Mannerist characteristics is especially prevalent in the work Laocoön. Painted in 1610,[42] it depicts the mythological tale of Laocoön, who warned the Trojans about the danger of the wooden horse which was presented by the Greeks as peace offering to the goddess Minerva. As a result, Minerva retaliated in revenge by summoning serpents to kill Laocoön and his two sons. Instead of being set against the backdrop of Troy, El Greco situated the scene near Toledo, Spain in order to "universalize the story by drawing out its relevance for the contemporary world."[42]

El Greco's unique style in Laocoön exemplifies many Mannerist characteristics. One that they are prevalent is the elongation of many of the human forms throughout the composition in conjunction with their serpentine movement, which provides a sense of elegance. An additional element of Mannerist style is the atmospheric effects in which El Greco creates a hazy sky and blurring of landscape in the background.

Benvenuto Cellini

Benvenuto Cellini created the Cellini Salt Cellar of gold and enamel in 1540 featuring Poseidon and Amphitrite (water and earth) placed in uncomfortable positions and with elongated proportions. It is considered a masterpiece of Mannerist sculpture.

Lavinia Fontana

Lavinia Fontana (1552–1614) was a Mannerist portraitist often acknowledged to be the first female career artist in Western Europe.[43] She was appointed to be the Portraitist in Ordinary at the Vatican.[44] Her style is characterized as being influenced by the Carracci family of painters by the colors of the Venetian School. She is known for her portraits of noblewomen, and for her depiction of nude figures, which was unusual for a woman of her time.[45]

Taddeo Zuccaro (or Zuccari)

Taddeo Zuccaro was born in Sant'Angelo in Vado, near Urbino, the son of Ottaviano Zuccari, an almost unknown painter. His brother Federico, born around 1540, was also a painter and architect.

Federico Zuccaro (or Zuccari)

Federico Zuccaro’s documented career as a painter began in 1550, when he moved to Rome to work under Taddeo, his elder brother. He went on to complete decorations for Pius IV, and help complete the fresco decorations at the Villa Farnese at Caprarola. Between 1563 and 1565, he was active in Venice with the Grimani family of Santa Maria Formosa. During his Venetian period, he traveled alongside Palladio in Friuli.

Joachim Wtewael

Joachim Wtewael (1566–1638) continued to paint in a Northern Mannerist style until the end of his life, ignoring the arrival of the Baroque art, and making him perhaps the last significant Mannerist artist still to be working. His subjects included large scenes with still life in the manner of Pieter Aertsen, and mythological scenes, many small cabinet paintings beautifully executed on copper, and most featuring nudity.

Giuseppe Arcimboldo

Giuseppe Arcimboldo is most readily known for his artworks that incorporate still life and portraiture.[46] His style is viewed as Mannerist with the assemblage style of fruits and vegetables in which its composition can be depicted in various ways—right side up and upside down.[46] Arcimboldo's artworks have also applied to Mannerism in terms of humor that it conveys to viewers, because it does not hold the same degree of seriousness as Renaissance works.[46] Stylistically, Arcimboldo's paintings are known for their attention to nature and concept of a "monstrous appearance."[46]

One of Arcimboldo's paintings which contains various Mannerist characteristics is, Vertumnus. Painted against a black background is a portrait of Rudolf II, whose body is composed of various vegetables, flowers, and fruits.[46] The painting is viewed as various levels as a joke and conveying a serious message. The joke of the painting communicates the humor of power which is that Emperor Rudolf II is hiding a dark inner self behind his public image.[46] On the other hand, the serious tone of the painting foreshadows the good fortune that would be prevalent during his reign.[46]

Vertumnus contains various Mannerist elements in terms of its composition and message. One element is the flat, black background which Arcimboldo utilizes to emphasize the status and identity of the Emperor, as well as highlighting the fantasy of his reign. In the portrait of Rudolf II, Arcimboldo also strays away from the naturalistic representation of the Renaissance, and explores the construction of composition by rendering him from a jumble of fruits, vegetables, plants and flowers. Another element of Mannerism which the painting portrays is the dual narrative of a joke and serious message; humor wasn't normally utilized in Renaissance artworks.

Jacopo Pontormo Joseph in Egypt, 1515–1518; Oil on wood; 96 x 109 cm; National Gallery, London

Jacopo Pontormo Joseph in Egypt, 1515–1518; Oil on wood; 96 x 109 cm; National Gallery, London- Rosso Fiorentino, Francois I Gallery, Château de Fontainebleau, France

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Autumn, 1573, oil on canvas, Louvre Museum, Paris

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Autumn, 1573, oil on canvas, Louvre Museum, Paris Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Vertumnus the god of seasons, 1591, Skokloster Castle

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Vertumnus the god of seasons, 1591, Skokloster Castle Bronzino, Portrait of Bia de' Medici, c. 1545

Bronzino, Portrait of Bia de' Medici, c. 1545 Alessandro Allori, Susanna and the Elders, 1561

Alessandro Allori, Susanna and the Elders, 1561 El Greco, Baptism, c. 1614

El Greco, Baptism, c. 1614

Mannerist architecture

Mannerist architecture was characterized by visual trickery and unexpected elements that challenged the Renaissance norms.[47] Flemish artists, many of whom had traveled to Italy and were influenced by Mannerist developments there, were responsible for the spread of Mannerist trends into Europe north of the Alps, including into the realm of architecture.[48] During the period, architects experimented with using architectural forms to emphasize solid and spatial relationships. The Renaissance ideal of harmony gave way to freer and more imaginative rhythms. The best known architect associated with the Mannerist style, and a pioneer at the Laurentian Library, was Michelangelo (1475–1564).[49] He is credited with inventing the giant order, a large pilaster that stretches from the bottom to the top of a façade.[50] He used this in his design for the Piazza del Campidoglio in Rome.

Prior to the 20th century, the term Mannerism had negative connotations, but it is now used to describe the historical period in more general, non-judgmental terms.[51] Mannerist architecture has also been used to describe a trend in the 1960s and 1970s that involved breaking the norms of modernist architecture while at the same time recognizing their existence.[52] Defining Mannerism in this context, architect and author Robert Venturi wrote "Mannerism for architecture of our time that acknowledges conventional order rather than original expression but breaks the conventional order to accommodate complexity and contradiction and thereby engages ambiguity unambiguously."[52]

Renaissance examples

An example of Mannerist architecture is the Villa Farnese at Caprarola,[53] in the rugged country side outside of Rome. The proliferation of engravers during the 16th century spread Mannerist styles more quickly than any previous styles.

Dense with ornament of "Roman" detailing, the display doorway at Colditz Castle exemplifies the northern style, characteristically applied as an isolated "set piece" against unpretentious vernacular walling.

From the late 1560s onwards, many buildings in Valletta, the new capital city of Malta, were designed by the architect Girolamo Cassar in the Mannerist style. Such buildings include St. John's Co-Cathedral, the Grandmaster's Palace and the seven original auberges. Many of Cassar's buildings were modified over the years, especially in the Baroque period. However, a few buildings, such as Auberge d'Aragon and the exterior of St. John's Co-Cathedral, still retain most of Cassar's original Mannerist design.[54]

One of the best examples of Mannerist architecture: Palazzo Te in Mantova, designed by Giulio Romano

One of the best examples of Mannerist architecture: Palazzo Te in Mantova, designed by Giulio Romano Giulio Romano, Pallazo Ducale in Mantova

Giulio Romano, Pallazo Ducale in Mantova Own house of Giulio Romano in Mantova

Own house of Giulio Romano in Mantova Baldassare Peruzzi, Palazzo Massimo alle Colonne in Rome

Baldassare Peruzzi, Palazzo Massimo alle Colonne in Rome- Michelangelo, vestibule of Laurentian Library

St. John's Co-Cathedral in Valletta, Malta

St. John's Co-Cathedral in Valletta, Malta Cathedral Basilica of Salvador, Brazil, built between 1657–1746, a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[55]

Cathedral Basilica of Salvador, Brazil, built between 1657–1746, a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[55]

Mannerism in literature and music

In English literature, Mannerism is commonly identified with the qualities of the "Metaphysical" poets of whom the most famous is John Donne.[56] The witty sally of a Baroque writer, John Dryden, against the verse of Donne in the previous generation, affords a concise contrast between Baroque and Mannerist aims in the arts:

He affects the metaphysics, not only in his satires but in his amorous verses, where nature only should reign; and perplexes the minds of the fair sex with nice[57] speculations of philosophy when he should engage their hearts and entertain them with the softnesses of love.[58]:15 (italics added)

The rich musical possibilities in the poetry of the late 16th and early 17th centuries provided an attractive basis for the madrigal, which quickly rose to prominence as the pre-eminent musical form in Italian musical culture, as discussed by Tim Carter:

The madrigal, particularly in its aristocratic guise, was obviously a vehicle for the 'stylish style' of Mannerism, with poets and musicians revelling in witty conceits and other visual, verbal and musical tricks to delight the connoisseur.[59]

The word Mannerism has also been used to describe the style of highly florid and contrapuntally complex polyphonic music made in France in the late 14th century.[60] This period is now usually referred to as the ars subtilior.

Mannerism and theatre

The Early Commedia dell'Arte (1550–1621): The Mannerist Context by Paul Castagno discusses Mannerism's effect on the contemporary professional theatre.[61] Castagno's was the first study to define a theatrical form as Mannerist, employing the vocabulary of Mannerism and maniera to discuss the typification, exaggerated, and effetto meraviglioso of the comici dell'arte. See Part II of the above book for a full discussion of Mannerist characteristics in the commedia dell'arte. The study is largely iconographic, presenting a pictorial evidence that many of the artists who painted or printed commedia images were in fact, coming from the workshops of the day, heavily ensconced in the maniera tradition.

The preciosity in Jacques Callot's minute engravings seem to belie a much larger scale of action. Callot's Balli di Sfessania (literally, dance of the buttocks) celebrates the commedia's blatant eroticism, with protruding phalli, spears posed with the anticipation of a comic ream, and grossly exaggerated masks that mix the bestial with human. The eroticism of the innamorate (lovers) including the baring of breasts, or excessive veiling, was quite in vogue in the paintings and engravings from the second School of Fontainebleau, particularly those that detect a Franco-Flemish influence. Castagno demonstrates iconographic linkages between genre painting and the figures of the commedia dell'arte that demonstrate how this theatrical form was embedded within the cultural traditions of the late cinquecento.[62]

Commedia dell'arte, disegno interno, and the discordia concors

Important corollaries exist between the disegno interno, which substituted for the disegno esterno (external design) in Mannerist painting. This notion of projecting a deeply subjective view as superseding nature or established principles (perspective, for example), in essence, the emphasis away from the object to its subject, now emphasizing execution, displays of virtuosity, or unique techniques. This inner vision is at the heart of commedia performance. For example, in the moment of improvisation the actor expresses his virtuosity without heed to formal boundaries, decorum, unity, or text. Arlecchino became emblematic of the mannerist discordia concors (the union of opposites), at one moment he would be gentle and kind, then, on a dime, become a thief violently acting out with his battle. Arlecchino could be graceful in movement, only in the next beat, to clumsily trip over his feet. Freed from the external rules, the actor celebrated the evanescence of the moment; much the way Benvenuto Cellini would dazzle his patrons by draping his sculptures, unveiling them with lighting effects and a sense of the marvelous. The presentation of the object became as important as the object itself.

Neo-Mannerism

According to art critic Jerry Saltz, "Neo-Mannerism" (new Mannerism) is among several clichés that are "squeezing the life out of the art world".[63] Neo-Mannerism describes art of the 21st century that is turned out by students whose academic teachers "have scared [them] into being pleasingly meek, imitative, and ordinary".[63]

See also

- Counter-Maniera

- Mannerist architecture and sculpture in Poland

- Timeline of Italian artists to 1800

Notes

- Moffett, Marian; Fazio, Michael W.; Wodehouse, Lawrence (2003). A World History of Architecture. Laurence King Publishing. p. 330. ISBN 978-1-85669-371-4.

- Bousquet, Jacques (1964). Mannerism: The Painting and Style of the Late Renaissance. Braziller.

- Freedberg 1971, 483.

- Gombrich 1995, .

- "Mannerism: Bronzino (1503–1572) and his Contemporaries". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 19 May 2013.

- Art and Illusion, E. H. Gombrich, ISBN 9780691070001

- "the-mannerist-style". artsconnected.org. Archived from the original on 20 June 2012. Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- John Shearman, "Maniera as an Aesthetic Ideal", in Cheney 2004, 37.

- Cheney 1997, 17.

- Briganti 1961, 6.

- Mirollo 1984,

- Shearman 1967.

- Grossmann 1965.

- Smyth 1962, 1–2.

- Cheney , "Preface", xxv–xxxii, and Manfred Wundram, "Mannerism," Grove Art Online. Oxford University Press, [accessed 23 April 2008].

- "The brilliant neurotics of the late Renaissance". The Spectator. 17 May 2014.

- Friedländer 1965,

- Freedberg 1993, 175–77.

- Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects

- Friedländer 1965,.

- Manfred Wundram, "Mannerism," Grove Art Online. Oxford University Press, [accessed 23 April 2008].

- Freedberg 1965.

- Shearman 1967, p. 19

- Briganti 1961, 32–33

- Briganti 1961, 13.

- Friedländer 1957, .

- Summerson 1983, 157–72.

- Olson, 179–182

- Olson, 183–187

- Olson, 182–183

- Olson, 194–202

- Marchetti Letta, Elisabetta (1995). Pontormo, Rosso Fiorentino. Constable. p. 6. ISBN 0094745501. OCLC 642761547.

- Smart, Alastair (1972). The Renaissance and Mannerism in Northern Europe and Spain. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. p. 118.

- Cox-Rearick, Janet. "Pontormo, Jacopo da". Grove Art Online. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- Cecchi, Alessandro; Bronzino, Agnolo; vans, Christopher E (1996). Bronzino. Antella, Florence: The Library of Great Masters. p. 20.

- Stokstad, Marilyn; Cothren, Michael Watt (2011). Art History. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall. pp. 663.

- Nichols, Tom (1 October 2015). Tintoretto : tradition and identity. p. 234. ISBN 9781780234816. OCLC 970358992.

- "National Gallery of Art – El Greco". Nga.gov. Retrieved 19 May 2013.

- "Metropolitan Museum of Art El Greco (Domenikos Theotokopoulos) (1541–1614)". Metmuseum.org. Retrieved 19 May 2013.

- Marías, Fernando (2003). "Greco, El". Grove Art Online. Retrieved 1 April 2019.

- Lambraki-Plaka, Marina. El Greco-The Greek. Kastaniotis. pp. 47–49. ISBN 960-03-2544-8.

- Davies, David; Greco, J. H; Metropolitan Museum of Art; National Gallery (2003). El Greco. London: National Gallery Company. p. 245.

- Murphy, Caroline (2003). Lavinia Fontana : a painter and her patrons in sixteenth-century Bologna. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300099134. OCLC 50478433.

- Cheney, Liana (2000). Alicia Craig Faxon; Kathleen Lucey Russo (eds.). Self-portraits by women painters. Aldershot, Hants, England: Ashgate. ISBN 1859284248. OCLC 40453030.

- "Lavinia Fontana's nude Minervas. – Free Online Library". www.thefreelibrary.com. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- Kaufmann, Thomas DaCosta (2010). Arcimboldo. University of Chicago Press. p. 167. doi:10.7208/chicago/9780226426884.001.0001. ISBN 9780226426877.

- "Style Guide: Mannerism". Victoria and Albert. 19 December 2012. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- Wundram, Manfred (1996). Dictionary of Art. Grove. p. 281.

- Peitcheva, Maria (2016). Michelangelo: 240 Colour Plates. StreetLib. p. 2. ISBN 978-88-925-7791-6.

- Mark Jarzombek, "Pilaster Play" (PDF), Thresholds, 28 (Winter 2005): 34–41

- Arnold Hauser. Mannerism: The Crisis of the Renaissance and the Origins of Modern Art. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press,1965).

- Venturi, Robert. "Architecture as Signs and Systems" (PDF). Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- Coffin David, The Villa in the Life of Renaissance Rome, Princeton University Press, 1979: 281–85

- Ellul, Michael (2004). "In search of Girolamo Cassar: An unpublished manuscript at the State Archives of Lucca" (PDF). Melita Historica. XIV (1): 37. ISSN 1021-6952. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 March 2016.

- "Historic Centre of Salvador de Bahia", World Heritage List, Paris: UNESCO

- "Gale eBooks – Document – John Donne". go.gale.com. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- 'Nice' in the sense of 'finely reasoned.'

- Gardner, Helen (1957). Metaphysical Poets. Oxford University Press, London. ISBN 9780140420388. Retrieved 15 August 2014.

- Carter 1991, 128.

- Apel 1946–47, 20.

- Castagno 1992,.

- Castagno 1994, .

- Saltz, Jerry (10 October 2013). "Jerry Saltz on Art's Insidious New Cliché: Neo-Mannerism". Vulture. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

References

- Apel, Willi. 1946–47. "The French Secular Music of the Late Fourteenth Century". Acta Musicologica 18: 17–29.

- Briganti, Giuliano. 1962. Italian Mannerism, translated from the Italian by Margaret Kunzle. London: Thames and Hudson; Princeton: Van Nostrand; Leipzig: VEB Edition. (Originally published in Italian, as La maniera italiana, La pittura italiana 10. Rome: Editori Riuniti, 1961).

- Carter, Tim. 1991. Music in Late Renaissance and Early Baroque Italy. London: Amadeus Press. ISBN 0-9313-4053-5

- Castagno, Paul C. 1994. The Early Commedia Dell'arte (1550–1621): The Mannerist Context. New York: P. Lang. ISBN 0-8204-1794-7.

- Cheney, Liana de Girolami (ed.). 2004. Readings in Italian Mannerism, second printing, with a foreword by Craig Hugh Smyth. New York: Peter Lang. ISBN 0-8204-7063-5. (Previous edition, without the forward by Smyth, New York: Peter Lang, 1997. ISBN 0-8204-2483-8).

- Cox-Rearick, Janet. "Pontormo, Jacopo da." Grove Art Online.11 Apr 2019. http://www.oxfordartonline.com/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000068662.

- Davies, David, Greco, J. H Elliott, Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.), and National Gallery (Great Britain). El Greco. London: National Gallery Company, 2003.

- Freedberg, Sidney J. 1965. "Observations on the Painting of the Maniera". Reprinted in Cheney 2004, 116–23.

- Freedberg, Sidney J. 1971. Painting in Italy, 1500–1600, first edition. The Pelican History of Art. Harmondsworth and Baltimore: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-056035-1

- Freedberg, Sidney J. 1993. Painting in Italy, 1500–1600, 3rd edition, New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-05586-2 (cloth) ISBN 0-300-05587-0 (pbk)

- Friedländer, Walter. 1965. Mannerism and Anti-Mannerism in Italian Painting. New York: Schocken. LOC 578295 (First edition, New York: Columbia University Press, 1958.)

- Gombrich, E[rnst] H[ans]. 1995. The Story of Art, sixteenth edition. London: Phaidon Press. ISBN 0-7148-3247-2.

- Kaufmann, Thomas DaCosta. Arcimboldo : Visual Jokes, Natural History, and Still-Life Painting. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010. ProQuest Ebook Central.

- Lambraki-Plaka, Marina (1999). El Greco-The Greek. Kastaniotis. ISBN 960-03-2544-8.

- Marchetti Letta, Elisabetta, Jacopo Da Pontormo, and Rosso Fiorentino. Pontormo, Rosso Fiorentino. The Library of Great Masters. Antella, Florence: Scala, 199

- Marías, Fernando. 2003 "Greco, El." Grove Art Online. 2 April 2019. http://www.oxfordartonline.com/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000034199.

- Mirollo, James V. 1984. Mannerism and Renaissance Poetry: Concept, Mode, Inner Design. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-03227-7.

- Nichols, Tom. Tintoretto : Tradition and Identity. London: Reaktion, 1999.

- Shearman, John K. G. 1967. Mannerism. Style and Civilization. Harmondsworth: Penguin. Reprinted, London and New York: Penguin, 1990. ISBN 0-14-013759-9

- Olson, Roberta J.M., Italian Renaissance Sculpture, 1992, Thames & Hudson (World of Art), ISBN 9780500202531

- Smart, Alastair. The Renaissance and Mannerism in Northern Europe and Spain. The Harbrace History of Art. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1972.

- Smyth, Craig Hugh. 1992. Mannerism and Maniera, with an introduction by Elizabeth Cropper. Vienna: IRSA. ISBN 3-900731-33-0.

- Summerson, John. 1983. Architecture in Britain 1530–1830, 7th revised and enlarged (3rd integrated) edition. The Pelican History of Art.

Harmondsworth and New York: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-056003-3 (cased) ISBN 0-14-056103-X (pbk) [Reprinted with corrections, 1986; 8th edition, Harmondsworth and New York: Penguin, 1991.]

- Stokstad, Marilyn, and Michael Watt Cothren. Art History. 4th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall, 2011.

Further reading

- Gardner, Helen Louise. 1972. The Metaphysical Poets, Selected and Edited, revised edition. Introduction. Harmondsworth, England; New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-042038-X.

- Grossmann F. 1965. Between Renaissance and Baroque: European Art: 1520–1600. Manchester City Art Gallery

- Hall, Marcia B . 2001. After Raphael: Painting in Central Italy in the Sixteenth Century, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-48397-2.

- Pinelli, Antonio. 1993. La bella maniera: artisti del Cinquecento tra regola e licenza. Turin: Piccola biblioteca Einaudi. ISBN 88-06-13137-0

- Sypher, Wylie. 1955. Four Stages of Renaissance Style: Transformations in Art and Literature, 1400–1700. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday. A classic analysis of Renaissance, Mannerism, Baroque, and Late Baroque.

- Würtenberger, Franzsepp. 1963. Mannerism: The European Style of the Sixteenth Century. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston (Originally published in German, as Der Manierismus; der europäische Stil des sechzehnten Jahrhunderts. Vienna: A. Schroll, 1962).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mannerism. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Mannerism |