Art pottery

Art pottery is a term for pottery with artistic aspirations, made in relatively small quantities, mostly between about 1870 and 1930.[1] Typically, sets of the usual tableware items are excluded from the term; instead the objects produced are mostly decorative vessels such as vases, jugs, bowls and the like which are sold singly. The term originated in the later 19th century, and is usually used only for pottery produced from that period onwards. It tends to be used for ceramics produced in factory conditions, but in relatively small quantities, using skilled workers, with at the least close supervision by a designer or some sort of artistic director. Studio pottery is a step up, supposed to be produced in even smaller quantities, with the hands-on participation of an artist-potter, who often performs all or most of the production stages.[2] But the use of both terms can be elastic. Ceramic art is often a much wider term, covering all pottery that comes within the scope of art history, but "ceramic artist" is often used for hands-on artist potters in studio pottery.

%2C_ca._1900_(CH_18666929)_(cropped).jpg)

.jpg)

The term implied both a progressive design style and also a closer relationship between the design of a piece and its production process. Art pottery was part of the Arts and Crafts movement, and a reaction to the technically superb but over-ornamented wares made by the large European factories, especially in porcelain.[3] Later art pottery represented the ceramic arm of the Aesthetic Movement and Art Nouveau.[4] Many of the wares are earthenware or stoneware, and there is often an interest in East Asian ceramics, especially historical periods when the individual craftsmen had been allowed a large role in the design and decoration. There is often great interest in ceramic glaze effects, including lustreware, and relatively less in painted decoration (still less in transfer printing).[5]

.jpg)

Throwing pieces on the potter's wheel, which hardly played any part in the large factories of the day, was often used, and many pieces were effectively unique, especially in their glazes, applied in ways that encouraged random effects. Compared to the production processes in larger factories, where each stage usually involved different workers, the same worker often took a piece through several stages of production, though studio pottery typically took this even further, and several makers of art pottery, if they became successful, drifted back towards conventional factory methods, as cheaper and allowing larger quantities to be made.[6]

The most significant countries producing art pottery were Britain and France, soon followed by the United States. American art pottery has many similarities, but some differences,[7] with its European equivalents. The term is not often used outside the Western world, except in "folk art pottery", often used for some village-based mingei traditions in Japanese pottery.[8]

History

The movement was strongly linked with the fashion for national and international competitions and awards in the period, with the World's fairs the largest. America's first of these was the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia in 1876, which "was a critical catalyst for the development of the American Art Pottery movement", both because American commercial potteries exerted themselves to improve the artistic quality of the products specially made for exhibition, and because American visitors were exposed to a wider range of European and Asian ceramics than hitherto. Doulton appears to have exhibited over 500 pieces of its Lambeth art studio stoneware and Lambeth Faience, and these as well as French "barbotine" and Japanese pieces had a decisive influence on many individuals who went on to become significant in American art pottery.[9]

There were also close links with amateur china painting, which had become a very popular hobby, especially for middle-class women, in the same decades.[10] In London, the Regent Street jewellers Howell James & Co. became a leading showplace for both amateur and professional work, organizing exhibitions and competitions.[11]

Britain

.jpg)

The movement perhaps began in the 1860s. Unlike many terms for styles or movements in art, the name appears to have come from the producers, and was used of their wares by several English manufacturers by the 1870s. In 1870 or 1871 Mintons, one of the large Staffordshire pottery factories, founded in 1793, who had successfully tried to keep up with innovation in design,[12] opened their "Mintons Art Pottery Studio" in Kensington Gore, London.[13]

Very many art potteries were newly-established, especially in America, but in Europe many long-established ceramic manufacturers embraced the movement, usually by establishing dedicated sections of their business, kept apart from their higher-volume wares.[14] This was especially the case for large English firms who had become mainly associated with less glamorous utilitarian wares. Doulton & Co., later Royal Doulton, was hugely profitable from utilitarian stonewares, above all sewage and drain pipes, and able to experiment, establishing links with the nearby Lambeth School of Art. Doulton revived fine English stoneware, and raised its own profile; it is unclear whether the art wares of Lambeth ever made much profit.[15] Maw & Co was, with Mintons, one of the main makers of decorative encaustic tiles, but launched "Art Pottery" lines by the 1880s, some by Walter Crane, who had been designing tiles for them since the 1870s.[16]

The Doulton studios were unusual in this period in allowing the decorators, about half of them female, to sign or initial pieces, and several have acquired individual reputations, like the sisters Hannah and Florence Barlow. A report in The Art Journal on a visit to Mintons' "Art-pottery studio at South Kensington", run by the artist William Stephen Coleman, reported that the designers and decorators worked segregated by sex, and was at pains to stress the position of the ladies:[17]

... from twenty to twenty-five educated women, of good social position, employed without loss of dignity, and in an agreeable and profitable manner. All have received the necessary Art-instruction, either at the Central Training Schools at South Kensington, or at the schools at Queen's Square, or at Lambeth."

By 1895 the Doulton studios employed 345 female artists.[19]

Two of the biggest names, then and now, in the British art pottery scene, offer contrasting degrees of involvement in the actual production process. William de Morgan was not hands-on with the clay as a thrower,[20] while at least three of the four Martin Brothers were personally engaged in production. They are now regarded as among the earliest makers of studio pottery, but that term had not been devised at the time.[21] Another major figure, Christopher Dresser, was a designer whose name is closely associated with the Linthorpe Art Pottery, but may never have actually visited the works in Yorkshire (now Teeside);[22] he also designed for Mintons (porcelain) and other potteries.[23]

Victoria Bergesen groups the wares into broad stylistic groups. Firstly came stonewares and earthenwares that were initially strongly influenced by historical styles. Then there were painted wares that related to the Aesthetic Movement, and overlapped with amateur china painting. Another group made wares with a rural, folk art, style, often in very small potteries; this perhaps survived the longest, and from the 20th century is often called "craft pottery". Another group was interested in advanced glaze effects, whether trying to recreate historic Asian ones such as sang de boeuf glaze (for example Bernard Moore), or new experimental ones such as the still radioactive orange uranium glazes.[24] Then came another wave of hand-painting, but less realist, and more geometric and stylized. This style greatly influenced industrial wares after World War I.[25]

- Mintons plate, 1869, William Stephen Coleman (1829-1904), hand-painted in South Kensington

- Mintons "Secessionist Ware" vase, 1900s; a factory-made range

.jpg)

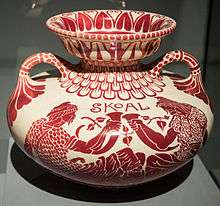

Skoal, Maw & Co vase designed by Walter Crane, c. 1885

Skoal, Maw & Co vase designed by Walter Crane, c. 1885

America

American pottery was made by some 200 studios and small factories across the country, with especially strong centres of production in Ohio (the Cowan, Lonhuda, Owens, Roseville, Rookwood, and Weller potteries) and Massachusetts (the Dedham, Grueby, Marblehead, and Paul Revere potteries). With some exceptions like the Rookwood Pottery Company, founded in 1880, most producers began making it after 1890 and many after 1900. Some were newly-established and other had been making other types of wares. Most of the potteries were forced out of business by the economic pressures of competition from commercial mass-production companies as well as the advent of World War I followed a decade later by the Great Depression.[26]

Hugh C. Robertson, Dedham Pottery, (CKAW) c. 1886-89, with crackle glaze

Hugh C. Robertson, Dedham Pottery, (CKAW) c. 1886-89, with crackle glaze- Rookwood Pottery Company vase by Albert Robert Valentien, 1893, earthenware with mahogany glaze

Van Briggle Pottery, 1903 vase by Artus Van Briggle

Van Briggle Pottery, 1903 vase by Artus Van Briggle.jpg) Paul Revere Pottery, c. 1911

Paul Revere Pottery, c. 1911

France

.jpg)

In continental Europe parts of the faience manufacturing sector had managed to survive the onslaught of English creamwares and bone china, and increasingly cheap hard-paste porcelain from local factories, and many of these embraced the movement. In France, which was the most important continental producer, the famous Service Rousseau designs in Creil-Montereau faience (1867) were early examples of Japonisme, and somewhat in the spirit of art pottery, although the service was commissioned by a wholesaler from Félix Bracquemond, an established artist, and the manufacture contracted out.[28]

The earliest significant figure was Théodore Deck, who founded his faience works in 1856, and initially explored styles and techniques from Islamic pottery with great success. When Japonisme arrived in the 1870s he embraced this and other art pottery trends with enthusiasm, finally conquering the French establishment when he was made art director of Sèvres porcelain in 1887. Several important figures from the next generation were trained by Deck.[29]

Ernest Chaplet was an artist and hands-on potter, mainly in stoneware, who later worked with Paul Gauguin, whose many ceramic sculptures cannot really be squeezed into the category of art pottery. Much of the ceramic output of Jean-Joseph Carriès, a sculptor who died young in 1894, was also sculpture, including many faces and heads, often with grotesque expressions, but he made several conventional pots, often with thick unctuous ash glaze effects in the Japanese style. Other leading figures were Auguste Delaherche, Edmond Lachenal, Pierre-Adrien Dalpayrat, a great creator of glazes, and Clément Massier. The large American-owned Limoges porcelain firm of Haviland & Co. was important in encouraging new styles, with much production being exported.[30] Their stand at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition was one of the important influences there on later American pottery, especially in its barbotine painted wares. These, thickly painted with slip, allowed similar effects to the Impressionist paintings being produced in the same period.[31]

The glaze specialist Taxile Doat moved in the opposite direction to others; after nearly 30 years at Sèvres he set up his own small studio in 1895, and in 1909 moved to teach and pot in America. Alexandre Bigot, originally a chemistry teacher, made some pottery himself, with individual glazes, but was mainly notable for his designs for Art Nouveau architectural ceramics, created by his own large firm.[32] Hector Guimard was an Art Nouveau architect and designer, mainly in metal (including the famous Paris Metro entries) but also designed ceramics, many for Sèvres.[33] A generation later, the Mougin brothers emerged around 1900, and worked in Art Nouveau and Art Deco styles until the 1930s.

Plate designed in 1867 by Félix Bracquemond, Service Rousseau

Plate designed in 1867 by Félix Bracquemond, Service Rousseau.jpg) Flask by Jean Carriès, c. 1890

Flask by Jean Carriès, c. 1890.jpg) French square sang de boeuf glaze vase by Ernest Chaplet, c. 1889

French square sang de boeuf glaze vase by Ernest Chaplet, c. 1889.jpg) Théodore Deck porcelain vase, 1895

Théodore Deck porcelain vase, 1895- Auguste Delaherche, porcelain cup, 1903

Netherlands

_%26_J._Schellink_(decoration)%2C_Haagsche_Plateelbakkerij%2C_Rozenburg%2C_Den_Haag%2C_1900%2C_porcelain_-_Hessisches_Landesmuseum_Darmstadt_-_Darmstadt%2C_Germany_-_DSC00816_(cropped).jpg)

In the Netherlands De Porceleyne Fles had been founded in Delft in 1653, but by 1840 was the only Delftware factory left in the city. After appointing Adolf Le Comte as designer in 1877, its products were shifted in the direction of art pottery, though still mostly using the traditional hand-painted blue and white pottery style.[34] In 1884 Theo Colenbrander, like Le Comte initially an architect, took over the Haagsche Plateelbakkerij, Rozenburg in The Hague, and was considerably more adventurous, but also with an emphasis on painting rather than adventurous shapes.[35] Later they turned with success to Art Nouveau, mostly in porcelain. Most of the best forms were designed by Jurriaan J. Kok and painted by Samuel Schellink, and in contrast the innovative, elegant and elongated shapes were a large part of the appeal.[36]

Hungary

The large firm of Zsolnay in Budapest specialized in architectural ceramics, introducing new glazes and finishes, but was also very alert to new trends in decorative pottery, with an uninhibited approach to design and colour. From the late 1860s until his death in 1900, it was led by Vilmos Zsolnay, son of the founder.[37] Many of Zsolnay's designs had a strongly nationalistic element, drawing shapes from ancient archaeological wares, Islamic ones from the long Ottoman occupation, and contemporary peasant pottery. Ornament and colour were influenced by these and traditional Hungarian clothing and embroidery, both peasant and aristocratic. Vilmos Zsolnay's sisters Julia and Terez were collectors of all these, and from the 1870s became involved in the design process of the firm.[38]

Porcelain and Art Nouveau

.jpg)

The Art pottery movement very largely used forms of earthenware and stoneware, sometimes revelling in showing the clay body, and sometimes smothering it in thick glazes. The many large European porcelain companies generally stood aloof from these developments, concentrating on tableware, and often struggling to throw off what had become the deadening influence of Rococo and Neoclassical styles. In the 1870s most continued to produce an eclectic variety of revivalist styles, though sometimes experimenting with glazes, as at Meissen porcelain, which began to produce monochrome vases from 1883.[39]

The first major porcelain company to seriously change its styles was Royal Copenhagen, which made radical changes from 1883, when it was bought by Aluminia, an earthenware company. Arnold Krog, an architect under 30 with no practical experience of the industry, was made artistic director the next year, and rapidly shifted designs in the same directions art pottery was exploring, commissioning many painters to design for the factory. Japanese influences were initially very strong. The new wares soon won prizes at various international exhibitions, and most of the large porcelain makers began to move in similar directions,[40] causing problems for the smaller art potteries.

Art Nouveau produced an upsurge in adventurous art glass, rather to the detriment of pottery. The French artist Émile Gallé was rather typical, making ceramics early in his career, but largely abandoning them for glass by 1892 (when young he took over the family's factories making both).[41]

In European countries not mentioned above, art pottery was slow to develop, and by the 1890s all the large porcelain factories in Europe were at least beginning to commission designs in Art Nouveau and other styles,[42] tending to suppress the development of smaller potteries. The Blaue Rispe tableware pattern by Richard Riemerschmid for Meissen is an example – this was not popular on first launch, but was revived much later.[43] Max Laeuger, mainly an architect, was the only very significant 19th-century German art potter, as a designer only, and in an Art Nouveau style from the late 1890s.[44] To a large extent, small art potteries after Art Nouveau are called studio pottery, and began exploring new styles and imperatives,[45] although many potteries continued to make pottery in the old spirit until at least World War II, especially in America.[46]

- Vase with Japanese wild carp, shape by Arnold Krog and Soren Bech Jacobsen, 1887, decorated by August F. Hallin, 1888, Royal Copenhagen, porcelain

.jpg) Max Laeuger, c. 1898, barbotine on earthenware

Max Laeuger, c. 1898, barbotine on earthenware Plate in Richard Riemerschmid's Blaue Rispe pattern for Meissen

Plate in Richard Riemerschmid's Blaue Rispe pattern for Meissen

Notes

- Bergesen, 213; Muller, 60; see also the ranges in the titles of the books in further reading. The term has had a rather longer life in America.

- Cooper, 206; Jacobs, 19; Osborne, 132; this is famously and most emphatically stated by Bernard Leach on the first page of his A Potter's Book (Faber, 1940)

- Savage, 24–25

- Sullivan; Bergesen, 213

- Bergesen, 246; Sullivan

- Jacobs, 17–21; Ellison, 261–262; Osborne, 132

- Jacobs, 17–18

- Wendy Jones Nakanishi, "The Anxiety of Influence: Ambivalent Relations Between Japan's 'Mingei' and Britain's 'Arts and Crafts' Movements", Electronic Journal of Japanese Studies, 28 October 2008; Moeran, Brian, Folk Art Potters of Japan: Beyond an Anthropology of Aesthetics, 2013, Routledge, ISBN 1136796738, 9781136796739

- Ellison, 27–45 (quoted); Mohr, Richard D., Ohr, George E., Pottery, Politics, Art: George Ohr and the Brothers Kirkpatrick, 2–3, 2003, University of Illinois Press, ISBN 0252027892, 9780252027895, google books

- Anderson, 128–140; Ellison, 263

- Anderson, 128–140

- Mundt, 24

- "Minton's Art Pottery Studio (Biographical details)", British Museum

- Wood, 69: Bergesen 213, and see entries for individual companies in both

- Wood, 76–83; Bergeson, 213–217; Mundt, 24; Jacobs, 18

- Bergesen, 557–567

- p. 100

- Wood, 96–97

- Vincentelli, Moira, Women and Ceramics: Gendered Vessels, 2000, Manchester University Press, ISBN 0719038405, 9780719038402, 91

- "William de Morgan", Morgan Foundation; Jacobs, 17

- Wood, 91–93; Bergesen, 218–219; Cooper, 206; Aberystwyth University, page with bio & nearly 40 images

- Bergesen, 246

- Bergesen, 408–409

- Bergesen, 213, 224 on uranium glazes by Pilkington's Lancastrian Pottery & Tiles

- Bergesen, 213

- Rago and Perrault

- Jardinière with landscape c. 1880, Haviland & Co. American and French

- Sullivan

- "Théodore Deck and the Islamic Style", by Frederica Todd Harlow, from Aramco World; Sullivan

- Sullivan

- Ellison, 43–53

- "Alexandre Bigot", Jason Jacques Gallery

- Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. "Hector Guimard". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- Muller, 60. It never made "porceleyne" until later, but Delftware faience.

- Muller, 60

- Battie, 163

- Mundt, 23–24

- Mundt, 37–39, 42. See also the next chapter on "The Creation of a National Style of Ornamentation at the End of the Nineteenth Century"

- Battie, 161–162; Mundt, 23–26,

- Battie, 162–163; Mundt, 30–31

- Arwas, 12–23; Mundt, 31–32

- Mundt, 23–26, 30, 33

- Grove, 97

- "Max Laeuger", Les Arts décoratifs, Centre de documentation des musées (in French)

- Hill, Rosemary, "Writing about the studio crafts", 190–198, in The Culture of Craft, Ed. Peter Dormer, 1997, Manchester University Press, ISBN 0719046181, 9780719046186, google books

- Wood, 72 and 87, where he includes potteries founded in 1974 and 1997 in his chapter on "art stoneware".

References

- Anderson, Anne, in Crafting the Woman Professional in the Long Nineteenth Century: Artistry and Industry in Britain, editors Kyriaki Hadjiafxendi, Patricia Zakreski, 2016, Routledge, ISBN 1317158652, 9781317158653, google books

- Arwas, Victor, The Art of Glass: Art Nouveau to Art Deco, 1996, Sunderland Museum and Art Gallery / Papadakis Publisher, ISBN 1901092003, 9781901092004, google books

- Battie, David, ed., Sotheby's Concise Encyclopedia of Porcelain, 1990, Conran Octopus, ISBN 1850292515

- Bergesen, Victoria, Bergesen's Price Guide: British Ceramics, 1992, Barrie & Jenkins, ISBN 0712653821

- Cooper, Emmanuel, in Pottery in the Making: World Ceramic Traditions, Freestone, Ian, Gaimster, David R. M. (eds), 1997, British Museum Publications, ISBN 071411782X

- "Ellison": American Art Pottery: The Robert A. Ellison Jr. Collection, Authors: Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen, Martin Eidelberg, Adrienne Spinozzi, 2018, Metropolitan Museum of Art, ISBN 1588395960, 9781588395962, google books

- "Grove", "Meissen Porcelain Factory", in The Grove Encyclopedia of Decorative Arts (Volume 1 of Two-volume Set), ed., Gordon Campbell, 2006, Oxford University Press, USA, ISBN 0195189485, 9780195189483, ISBN 0195189485, 9780195189483, google books

- Jacobs, Richard, in Friendship Forged in Fire: British Ceramics in America, 2013, American Museum of Ceramic Art / Lulu.com, ISBN 0981672876, 9780981672878, google books

- Muller, Sheila D. (ed.), Dutch Art: An Encyclopedia, 2013, Routledge, ISBN 1135495742, 9781135495749, google books

- Mundt, Barbara, in Hungarian Ceramics from the Zsolnay Manufactory, 1853–2001, ed. Ács, Piroska et al, 2002, Yale University Press, ISBN 0300097042, 9780300097047, google books

- Osborne, Harold (ed), The Oxford Companion to the Decorative Arts, 1975, OUP, ISBN 0198661134

- Rago, David, and Suzanne Perrault. American Art Pottery: How to Compare and Value. Mitchell Beazley, 2001.

- Savage, George, Porcelain Through the Ages, Penguin, (2nd edn.) 1963

- Sullivan, Elizabeth, "French Art Pottery", In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2014, online

- Wood, Frank L., The World of British Stoneware: Its History, Manufacture and Wares, 2014, Troubador Publishing Ltd, ISBN 178306367X, 9781783063673, google books

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Art pottery. |

Just general books are given here; there are also large numbers of books on individual potteries.

- Bergesen, Victoria and Godden, Geoffrey A., Encyclopaedia of British Art Pottery, 1992

- Coysh, Arthur Wilfred, British Art Pottery, 1870–1940, 1976, David and Charles, ISBN 0715372521, 9780715372524

- Cooper-Hewitt Museum. American Art Pottery. University of Washington Press, 1987.

- Haslam, Malcolm, English art pottery, 1865–1915, 1975, Antique Collectors' Club, ISBN 090202826X, 9780902028265

- Opie, Jennifer Hawkins. "The New Ceramics: Engaging with the Spirit." In Art Nouveau, 1890–1914, pp. 193–207. London: V&A Publications, 2000.