Realism (art movement)

Realism was an artistic movement that emerged in France in the 1840s, around the 1848 Revolution.[1] Realists rejected Romanticism, which had dominated French literature and art since the early 19th century. Realism revolted against the exotic subject matter and the exaggerated emotionalism and drama of the Romantic movement. Instead, it sought to portray real and typical contemporary people and situations with truth and accuracy, and not avoiding unpleasant or sordid aspects of life. The movement aimed to focus on unidealized subjects and events that were previously rejected in art work. Realist works depicted people of all classes in situations that arise in ordinary life, and often reflected the changes brought by the Industrial and Commercial Revolutions. Realism was primarily concerned with how things appeared to the eye, rather than containing ideal representations of the world.[2] The popularity of such "realistic" works grew with the introduction of photography—a new visual source that created a desire for people to produce representations which look objectively real.

The Realists depicted everyday subjects and situations in contemporary settings, and attempted to depict individuals of all social classes in a similar manner. Gloomy earth toned palettes were used to ignore beauty and idealization that was typically found in art. This movement sparked controversy because it purposefully criticized social values and the upper classes, as well as examining the new values that came along with the industrial revolution. Realism is widely regarded as the beginning of the modern art movement due to the push to incorporate modern life and art together.[3] Classical idealism and Romantic emotionalism and drama were avoided equally, and often sordid or untidy elements of subjects were not smoothed over or omitted. Social realism emphasizes the depiction of the working class, and treating them with the same seriousness as other classes in art, but realism, as the avoidance of artificiality, in the treatment of human relations and emotions was also an aim of Realism. Treatments of subjects in a heroic or sentimental manner were equally rejected.[4]

Realism as an art movement was led by Gustave Courbet in France. It spread across Europe and was influential for the rest of the century and beyond, but as it became adopted into the mainstream of painting it becomes less common and useful as a term to define artistic style. After the arrival of Impressionism and later movements which downgraded the importance of precise illusionistic brushwork, it often came to refer simply to the use of a more traditional and tighter painting style. It has been used for a number of later movements and trends in art, some involving careful illusionistic representation, such as Photorealism, and others the depiction of "realist" subject matter in a social sense, or attempts at both.

Beginnings in France

The Realist movement began in the mid-19th century as a reaction to Romanticism and History painting. In favor of depictions of 'real' life, the Realist painters used common laborers, and ordinary people in ordinary surroundings engaged in real activities as subjects for their works. The chief exponents of Realism were Gustave Courbet, Jean-François Millet, Honoré Daumier, and Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot.[5][6][7] Jules Bastien-Lepage is closely associated with the beginning of Naturalism, an artistic style that emerged from the later phase of the Realist movement and heralded the arrival of Impressionism.[8]

Realists used unprettified detail depicting the existence of ordinary contemporary life, coinciding in the contemporaneous naturalist literature of Émile Zola, Honoré de Balzac, and Gustave Flaubert.[9]

Courbet was the leading proponent of Realism and he challenged the popular history painting that was favored at the state-sponsored art academy. His groundbreaking paintings A Burial at Ornans and The Stonebreakers depicted ordinary people from his native region. Both paintings were done on huge canvases that would typically be used for history paintings.[9] Although Courbet's early works emulated the sophisticated manner of Old Masters such as Rembrandt and Titian, after 1848 he adopted a boldly inelegant style inspired by popular prints, shop signs, and other work of folk artisans.[10] In The Stonebreakers, his first painting to create a controversy, Courbet eschewed the pastoral tradition of representing human subjects in harmony with nature. Rather, he depicted two men juxtaposed against a charmless, stony roadside. The concealment of their faces emphasizes the dehumanizing nature of their monotonous, repetitive labor.[10]

Jean-François Millet, The Gleaners, 1857

Jean-François Millet, The Gleaners, 1857_-_The_Third-Class_Carriage_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg) Honoré Daumier, The Third Class Wagon, 1862–64

Honoré Daumier, The Third Class Wagon, 1862–64

Jean-François Millet, The Sower, 1850

Jean-François Millet, The Sower, 1850 Gustave Courbet, Le Sommeil (Sleep), 1866, Petit Palais, Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris

Gustave Courbet, Le Sommeil (Sleep), 1866, Petit Palais, Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris

Édouard Manet, Breakfast in the Studio (the Black Jacket), New Pinakothek, Munich, Germany, 1868

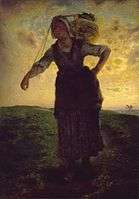

Édouard Manet, Breakfast in the Studio (the Black Jacket), New Pinakothek, Munich, Germany, 1868 Jean-François Millet, A Norman Milkmaid at Gréville, 1871

Jean-François Millet, A Norman Milkmaid at Gréville, 1871

.jpg) Jules Breton, The Song of the Lark, 1884

Jules Breton, The Song of the Lark, 1884_-_Jules_Breton.jpg) Jules Breton, The End of the Working Day, 1886–87

Jules Breton, The End of the Working Day, 1886–87

Beyond France

_-_Volga_Boatmen_(1870-1873).jpg)

The French Realist movement had stylistic and ideological equivalents in all other Western countries, developing somewhat later. The Realist movement in France was characterized by a spirit of rebellion against powerful official support for history painting. In countries where institutional support of history painting was less dominant, the transition from existing traditions of genre painting to Realism presented no such schism.[10] An important Realist movement beyond France was the Peredvizhniki or Wanderers group in Russia who formed in the 1860s and organized exhibitions from 1871 included many realists such as genre artist Vasily Perov, landscape artists Ivan Shishkin, Alexei Savrasov, and Arkhip Kuindzhi, portraitist Ivan Kramskoy, war artist Vasily Vereshchagin, historical artist Vasily Surikov and, especially, Ilya Repin, who is considered by many to be the most renowned Russian artist of the 19th century.

Courbet's influence was felt most strongly in Germany, where prominent realists included Adolph Menzel, Wilhelm Leibl, Wilhelm Trübner, and Max Liebermann. Leibl and several other young German painters met Courbet in 1869 when he visited Munich to exhibit his works and demonstrate his manner of painting from nature.[12] In Italy the artists of the Macchiaioli group painted Realist scenes of rural and urban life. The Hague School were Realists in the Netherlands whose style and subject matter strongly influenced the early works of Vincent van Gogh.[10] In Britain artists such as the American James Abbot McNeill Whistler, as well as English artists Ford Madox Brown, Hubert von Herkomer and Luke Fildes had great success with realist paintings dealing with social issues and depictions of the "real" world.

In the United States, Winslow Homer and Thomas Eakins were important Realists and forerunners of the Ashcan School, an early-20th-century art movement largely based in New York City. The Ashcan School included such artists as George Bellows and Robert Henri, and helped to define American realism in its tendency to depict the daily life of poorer members of society.

Later on in America, the term realism took on various new definitions and adaptations once the movement hit the U.S. Surrealism and magical realism developed out of the French realist movement in the 1930s, and in the 1950s new realism developed. This sub-movement considered art to exist as a thing in itself opposed to representations of the real world. In modern-day America, realism art is generally regarded as anything that does not fall into abstract art, therefore including mostly art that depicts realities.[2]

Illarion Pryanishnikov, Jokers. Gostiny Dvor in Moscow, 1865

Illarion Pryanishnikov, Jokers. Gostiny Dvor in Moscow, 1865 Konstantin Savitsky, Repairing the Railway, 1874

Konstantin Savitsky, Repairing the Railway, 1874 Ivan Shishkin, A Rye Field, 1878

Ivan Shishkin, A Rye Field, 1878 Wilhelm Leibl, The Village Politicians, 1877

Wilhelm Leibl, The Village Politicians, 1877 Adolph Menzel, Rear of House and Backyard, ca. 1846

Adolph Menzel, Rear of House and Backyard, ca. 1846 Giovanni Fattori, Three Peasants in a Field, 1866–67

Giovanni Fattori, Three Peasants in a Field, 1866–67 Jan Hendrik Weissenbruch, Farmhouse Interior, between 1870 and 1903

Jan Hendrik Weissenbruch, Farmhouse Interior, between 1870 and 1903 Ford Madox Brown, The Last of England, 1852–1855

Ford Madox Brown, The Last of England, 1852–1855- Hubert von Herkomer, Hard Times, 1885

- Everett Shinn, Cross Streets of New York, 1899, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington DC

Robert Henri, Snow in New York, 1902, National Gallery of Art, Washington DC

Robert Henri, Snow in New York, 1902, National Gallery of Art, Washington DC John French Sloan, McSorley's Bar, 1912, Detroit Institute of Arts

John French Sloan, McSorley's Bar, 1912, Detroit Institute of Arts

References

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- "EBSCOhost Login". search.ebscohost.com. Retrieved 2019-02-25.

- "Realism Movement Overview". The Art Story. Retrieved 2019-02-25.

- Finocchio, Ross. "Nineteenth-Century French Realism". In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. online (October 2004)

- NGA Realism movement Archived 2014-07-14 at the Wayback Machine

- National Gallery glossary, Realism movement

- Philosophy of Realism

- Fry, Roger. 1920. "Vision and Design." London: Chatto & Windus. "An Essay in Æsthetics." 11-24. Accessed online on 13 March 2012 at "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-11-14. Retrieved 2017-09-09.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Nineteenth-Century French Realism | Essay | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History | The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Rubin, J. 2003. "Realism". Grove Art Online.

- National Gallery of Art

- Nationalgalerie (Berlin), and Françoise Forster-Hahn. 2001. Spirit of an Age: Nineteenth-Century Paintings From the Nationalgalerie, Berlin. London: National Gallery Company. p. 155. ISBN 1857099605

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Realism. |