Mandaeism

Mandaeism or Mandaeanism (Arabic: مَنْدَائِيَّة, Mandāʾīyah), also known as Sabaeanism (Arabic: صَابِئِيَّة, Ṣābiʾīyah), is a monotheistic and gnostic religion[1]:4 with a strongly dualistic cosmology. Its adherents, the Mandaeans, revere Adam, Abel, Seth, Enos, Noah, Shem, Aram, and especially John the Baptist. The Mandaeans have been counted among the Semites and speak a dialect of Eastern Aramaic known as Mandaic. The name 'Mandaean' is said to come from the Aramaic manda meaning "knowledge", as does Greek gnosis.[2][3] Within the Middle East, but outside of their community, the Mandaeans are more commonly known as the Arabic: صُبَّة Ṣubba (singular: Ṣubbī) or Sabians. The term Ṣubba is derived from the Aramaic root related to baptism, the neo-Mandaic is Ṣabi.[4] Occasionally, Mandaeans are called "Christians of Saint John".[5]

| Part of a series on |

| Mandaeism |

|---|

|

|

Related religious groups |

|

Scriptures |

| Religion portal |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Influenced by |

In the Quran, the "Sabians" (Arabic: الصَّابِئُون, aṣ-Ṣābiʾūn) are mentioned three times alongside Jews and Christians. Most critical scholars today believe this term refers to the Manichaeans/Elkaisaites, an Abrahamic religious group that followed Jesus and was unrelated to the gnostic Mandaeans (who rejected Jesus). Confusion of the two occurs primarily among non-Arabic speakers, to whom the Quranic word aṣ-Ṣābiʾūn (from the root ص ب أ) seems similar to the word Ṣubba (from the root ص ب ب).

According to most scholars, Mandaeaism originated sometime in the first three centuries CE, in either southwestern Mesopotamia or the Syro-Palestinian area.[6] However, some scholars take the view that Mandaeanism is older and dates from pre-Christian times.[7]

The religion has been practised primarily around the lower Karun, Euphrates and Tigris and the rivers that surround the Shatt-al-Arab waterway, part of southern Iraq and Khuzestan Province in Iran. There are thought to be between 60,000 and 70,000 Mandaeans worldwide.[8] Until the Iraq War, almost all of them lived in Iraq.[9] Many Mandaean Iraqis have since fled their country because of the turmoil created by the 2003 invasion of Iraq and subsequent occupation by U.S. armed forces, and the related rise in sectarian violence by Muslim extremists.[10] By 2007, the population of Mandaeans in Iraq had fallen to approximately 5,000.[9]

The Mandaeans have remained separate and intensely private. Reports of them and of their religion have come primarily from outsiders: particularly from Julius Heinrich Petermann, an Orientalist[11] as well as from Nicolas Siouffi, a Syrian Christian who was the French vice-consul in Mosul in 1887,[12][13] and British cultural anthropologist Lady E. S. Drower. There is an early if highly prejudiced account by the French traveller Jean-Baptiste Tavernier[14] from the 1650s.

Etymology

The term Mandaic or Mandaeic Mandaeism comes from Classical Mandaic Mandaiia and appears in Neo-Mandaic as Mandeyānā. On the basis of cognates in other Aramaic dialects, Semiticists such as Mark Lidzbarski and Rudolf Macuch have translated the term manda, from which Mandaiia derives, as "knowledge" (cf. Aramaic: מַנְדַּע mandaʻ in Dan. 2:21, 4:31, 33, 5:12; cf. Hebrew: מַדַּע maddaʻ, with characteristic assimilation of /n/ to the following consonant, medial -nd- hence becoming -dd-[15]). This etymology suggests that the Mandaeans may well be the only sect surviving from Late Antiquity to identify themselves explicitly as Gnostics.

The words deism and theism are both derived from words meaning "god": Latin deus and Greek theos (θεός). The word déiste first appears in French in 1564 in a work by a Swiss Calvinist named Pierre Viret[16] but was generally unknown in France until the 1690s when Pierre Bayle published his famous Dictionary, which contained an article on Viret.[17]

Other scholars derive the term mandaiia from Mandā d-Heyyi (Mandaic Manda ḏ'Hayyi "Knowledge of Life," in reference to the chief divinity Hayyi Rabbi "the Great Life" or "Great Living God") or from the word Beth Manda,[1]:81[1]:167 which is the cultic hut in which many Mandaean ceremonies are performed (such as the baptism, which is the central sacrament of Mandaean religious life).

History

According to the Mandaean text the Haran Gawaita, the recorded history of the Mandaeans began when a group called the Nasoreans (the Mandaean priestly caste as opposed to the laity), left Judea/Palestine and migrated to Mesopotamia in the 1st century CE.[6] The reason given for this was their persecution in Jerusalem. The emigrants went first to Haran (probably Harran in modern day Turkey), or Hauran and then the Median hills in Iran, before finally settling in the southern provinces of Mesopotamia (modern day Iraq).[18] According to Edmondo Lupieri, as stated in his article on Encyclopedia Iranica, "The possible historical connection with John the Baptist, as seen in the newly translated Mandaean texts, convinced many (notably R. Bultmann) that it was possible, through the Mandaean traditions, to shed some new light on the history of John and on the origins of Christianity. This brought about a revival of the otherwise almost fully abandoned idea of their Palestinian origins. As the archeological discovery of Mandaean incantation bowls and lead amulets proved a pre-Islamic Mandaean presence in southern Mesopotamia, scholars were obliged to hypothesize otherwise unknown persecutions by Jews or by Christians to explain the reason for Mandaeans’ departure from Palestine."[19]

At the beginning of the Muslim conquest of Mesopotamia, the leader of the Mandaeans, Anush son of Danqa appeared before Muslim authorities showing them a copy of the Ginza Rabba, the Mandaean holy book, and proclaiming the chief Mandaean prophet to be John the Baptist, who is also mentioned in the Quran as Yahya Bin Zakariya. This identified Mandaeans with the Sabians who are mentioned in the Quran as being counted among the Ahl al-Kitāb (People of the Book). This provided Mandaeans a status as a legal minority religion within the Muslim Empire. The Mandaeans were henceforth associated with the Sabians and the Jewish Christian group the Elcesaites, on account of the location of all three in Mesopotamia in the early centuries CE, and the similarities in their beliefs. The importance of baptism in the rituals of all three is particularly marked. Like the Mandaeans, the Sabians were also said to be gnostics and descended from Noah. Mandaeans continue to be identified with Sabians up to the present day, but the exact relationship between the three groups remains unclear.

Around 1290, a learned Dominican Catholic from Tuscany, Ricoldo da Montecroce, or Ricoldo Pennini, was in Mesopotamia where he met the Mandaeans. He described them as follows:

A very strange and singular people, in terms of their rituals, lives in the desert near Baghdad; they are called Sabaeans. Many of them came to me and begged me insistently to go and visit them. They are a very simple people and they claim to possess a secret law of God, which they preserve in beautiful books. Their writing is a sort of middle way between Syriac and Arabic. They detest Abraham because of circumcision and they venerate John the Baptist above all. They live only near a few rivers in the desert. They wash day and night so as not to be condemned by God…

Mandaeans were called "Christians of Saint John" by members of the Discalced Carmelite mission in Basra during the 16th century, based upon their preliminary reports.[5] Some Portuguese Jesuits had also met some "Saint John Christians" around the Strait of Hormuz in 1559, when the Portuguese fleet fought with the Ottoman Turkish army in Bahrain. These Mandaean seemed to be willing to obey the Catholic Church. They learned and used the seven Catholic sacraments and the related ceremonies in their lives.[20]

Beliefs

Mandaeism, as the religion of the Mandaean people, is based more on a common heritage than on any set of religious creeds and doctrines. The corpus of Mandaean literature, though quite large, covers topics such as eschatology, the knowledge of God and the afterlife—in an unsystematic manner. Moreover, it is known only to the priesthood and a few laypeople.[21]

Fundamental tenets

According to E. S. Drower, the Mandaean Gnosis is characterized by nine features, which appear in various forms in other gnostic sects:[22]

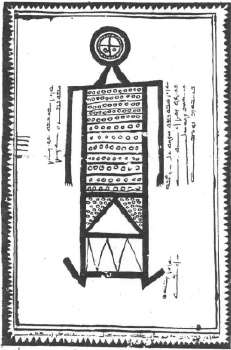

- A supreme formless Entity, the expression of which in time and space is creation of spiritual, etheric, and material worlds and beings. Production of these is delegated by It to a creator or creators who originated It. The cosmos is created by Archetypal Man, who produces it in similitude to his own shape.

- Dualism: a cosmic Father and Mother, Light and Darkness, Right and Left, syzygy in cosmic and microcosmic form.

- As a feature of this dualism, counter-types, a world of ideas.

- The soul is portrayed as an exile, a captive; her home and origin being the supreme Entity to which she eventually returns.

- Planets and stars influence fate and human beings, and are also places of detention after death.

- A savior spirit or savior spirits which assist the soul on her journey through life and after it to ‘worlds of light’.'

- A cult-language of symbol and metaphor. Ideas and qualities are personified.

- ‘Mysteries’, i.e. sacraments to aid and purify the soul, to ensure her rebirth into a spiritual body, and her ascent from the world of matter. These are often adaptations of existing seasonal and traditional rites to which an esoteric interpretation is attached. In the case of the Naṣoraeans this interpretation is based on the Creation story (see 1 and 2), especially on the Divine Man, Adam, as crowned and anointed King-priest.

- Great secrecy is enjoined upon initiates; full explanation of 1, 2, and 8 being reserved for those considered able to understand and preserve the gnosis.

Cosmology

As noted above Mandaean theology is not systematic. There is no one single authoritative account of the creation of the cosmos, but rather a series of several accounts. Some scholars, such as Edmondo Lupieri,[23] maintain that comparison of these different accounts may reveal the diverse religious influences upon which the Mandaeans have drawn and the ways in which the Mandaean religion has evolved over time.

In contrast with the religious texts of the western Gnostic sects formerly found in Syria and Egypt, the earliest Mandaean religious texts suggest a more strictly dualistic theology, typical of other Iranian religions such as Zoroastrianism, Zurvanism, Manichaeism, and the teachings of Mazdak. In these texts, instead of a large pleroma, there is a discrete division between light and darkness. The Mandaean God is known as Hayyi Rabbi (The Great Living God). [24]Other names used are Mare d'Rabuta (Lord of Greatness) and Melka d'Nhura (King of Light).[25][26]

Ptahil, the third emanation, alone does not constitute the demiurge but only fills that role insofar as he is the creator of the material world. Rather, Ptahil is the lowest of a group of three emanations, the other two being Yushamin (first emanation a.k.a. Joshamin) and Abathur, the second emanation. Abathur's demiurgic role consists of his sitting in judgment upon the souls of mortals. The role of Yushamin, the first emanation, is more obscure; wanting to create a world of his own, he was severely punished for opposing the King of Light. The name may derive from Iao haš-šammayim (in Hebrew: Yahweh "of the heavens").[27]

While Mandaeans agree with other gnostic sects that the world is a prison governed by the planetary archons, they do not view it as a cruel and inhospitable one.

Chief prophets

Mandaeans recognize several prophets. Yahia-Yohanna, known in Christianity as John the Baptist, is accorded a special status, higher than his role in Christianity and Islam. Mandaeans do not consider John to be the founder of their religion but revere him as one of their greatest teachers, tracing their beliefs back to Adam.

Mandaeans do not believe in Abraham, Moses or Jesus,[28] but recognize other prophetic figures from the Abrahamic religions, such as Adam, his son Seth, and his grandson Anush (Enos), as well as Nuh (Noah), Sam (Shem), and Ram (Aram), whom they consider to be their direct ancestors.

Mandaeans also do not recognize the Holy Spirit in the Talmud and Bible, who is known in Mandaic as Ruha, Ruha d-Qudsha, or Ruha Masțanita, in the same way. Instead of being viewed positively as a holy spirit, she is viewed negatively as the personification of the lower, emotional, and feminine elements of the human psyche.[29]

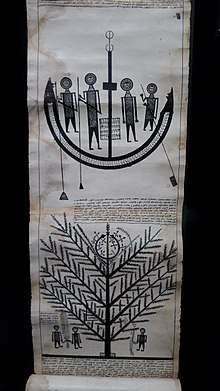

Scriptures

The Mandaeans have a large corpus of religious scriptures, the most important of which is the Ginza Rba or Ginza, a collection of history, theology, and prayers.[30] The Ginza Rba is divided into two halves—the Genzā Smālā or "Left Ginza", and the Genzā Yeminā or "Right Ginza". By consulting the colophons in the Left Ginza, Jorunn J. Buckley has identified an uninterrupted chain of copyists to the late second or early third century. The colophons attest to the existence of the Mandaeans or their predecessors during the late Parthian Empire at the very latest.

The oldest texts are lead amulets from about the third century CE, followed by magic bowls from about 600 CE. The important religious manuscripts are not older than the sixteenth century, with most coming from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.[31]

Although the Ginza continued to evolve under the rule of the Sasanian Empire and the Islamic caliphates, few textual traditions can lay claim to such extensive continuity.

Another important text is the Haran Gawaita which tells the history of the Mandaeans. According to this text, a group of Nasoraeans (Mandean priests) left Judea before the destruction of Jerusalem in the first century CE, and settled within the Parthian Empire.

Other important books include the Qolusta, the canonical prayerbook of the Mandaeans, which was translated by E. S. Drower.[32] One of the chief works of Mandaean scripture, accessible to laymen and initiates alike, is the Mandaean Book of John (Lidzbarski, Mark. "Das Johannesbuch der Mandäer". Giessen : Töpelmann.), which includes a dialogue between John and Jesus. In addition to the Ginza, Qolusta, and Draša, there is the Dīvān, which contains a description of the 'regions' the soul ascends through, and the Asfar Malwāshē, the "Book of the Zodiacal Constellations". Finally, there are some pre-Muslim artifacts that contain Mandaean writings and inscriptions, such as some Aramaic incantation bowls.

The language in which the Mandaean religious literature was originally composed is known as Mandaic, and is a member of the Aramaic family of dialects. It is written in a cursive variant of the Parthian chancellory script. Many Mandaean lay people do not speak this language, though some members of the Mandaean community resident in Iran and Iraq continue to speak Neo-Mandaic, a modern version of this language.

Worship

The two most important ceremonies in Mandaean worship are baptism (masbuta), and a mass for the dead or 'ascent of the soul ceremony' (masiqta).[18] Unlike other religions, baptism is not a one-off event but is performed every Sunday, the Mandaean holy day. Baptism usually involves full immersion in flowing water, and all rivers considered fit for baptism are called Yardena (after the River Jordan). After emerging from the water, the worshipper is anointed with holy oil and partakes of a communion of bread and water. The ascent of the soul ceremony can take various forms, but usually involves a ritual meal in memory of the dead. The ceremony is believed to help the souls of the departed on their journey through purgatory to the World of Light. Mandaean pray three times a day.[33][34]

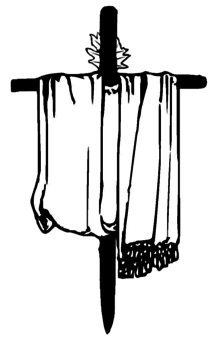

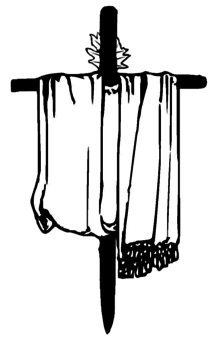

A mandī (Arabic: مندى) (Beth Manda) or Mashkhanna[35] is a place of worship for followers of Mandaeism. A mandī must be built beside a river in order to perform maṣbuta (or baptism) because water is an essential element in the Mandaean faith. Modern mandīs sometimes have a bath inside a building instead. Each mandi is adorned with a darfash, which is a cross of olive wood half covered with a piece of white pure silk cloth and seven branches of myrtle. The cross is not identified with the Christian cross. Instead the four arms of the cross symbolise the four corners of the universe, while the pure silk cloth represents the Light of God.[36] The seven branches of myrtle represent the seven days of creation.[37]

Mandaeans believe in marriage and procreation, and in the importance of leading an ethical and moral lifestyle in this world. They are pacifist and egalitarian, with the earliest attested Mandaean scribe being a woman, Shlama Beth Qidra, who copied the Left Ginza sometime in the 2nd century CE.[38] They also place a high priority upon family life. Mandaeans do not practice asceticism and detest circumcision.[25] Mandaeans will, however, abstain from strong drink and red meat.

Organisation

There is a strict division between Mandaean laity and the priests. According to E.S. Drower (The Secret Adam, p. ix):

[T]hose amongst the community who possess secret knowledge are called Naṣuraiia—Naṣoreans (or, if the emphatic ‹ṣ› is written as ‹z›, Nazorenes). At the same time the ignorant or semi-ignorant laity are called 'Mandaeans', Mandaiia—'gnostics.' When a man becomes a priest he leaves 'Mandaeanism' and enters tarmiduta, 'priesthood.' Even then he has not attained to true enlightenment, for this, called 'Naṣiruta', is reserved for a very few. Those possessed of its secrets may call themselves Naṣoreans, and 'Naṣorean' today indicates not only one who observes strictly all rules of ritual purity, but one who understands the secret doctrine.[39]

There are three grades of priesthood in Mandaeism: the tarmidia "disciples" (Neo-Mandaic tarmidānā), the ganzibria "treasurers" (from Old Persian ganza-bara "id.," Neo-Mandaic ganzeḇrānā) and the rišamma "leader of the people". This last office, the highest level of the Mandaean priesthood, has lain vacant for many years. At the moment, the highest office currently occupied is that of the ganzeḇrā, a title which appears first in a religious context in the Aramaic ritual texts from Persepolis (c. 3rd century BCE) and which may be related to the kamnaskires (Elamite <qa-ap-nu-iš-ki-ra> kapnuskir "treasurer"), title of the rulers of Elymais (modern Khuzestan) during the Hellenistic age. Traditionally, any ganzeḇrā who baptizes seven or more ganzeḇrānā may qualify for the office of rišamma, though the Mandaean community has yet to rally as a whole behind any single candidate.

The contemporary priesthood can trace its immediate origins to the first half of the 19th century. In 1831, an outbreak of cholera devastated the region and eliminated most if not all of the Mandaean religious authorities. Two of the surviving acolytes (šgandia), Yahia Bihram and Ram Zihrun, reestablished the priesthood on the basis of their own training and the texts that were available to them.

In 2009, there were two dozen Mandaean priests in the world, according to the Associated Press.[40] However, according to the Mandaean Society in America[41] the number of priests has been growing in recent years.

Relations with other groups

The Mandaeans have been identified with several groups, in particular the Sabians and the Elkasaites. Other groups such as the Nazerences and the Dositheans have also been identified with the Mandaeans. The exact relation of all these groups to one another is a difficult question. But they do share many common beliefs, in accordance with other ancient Middle Eastern religions such as Yazdaism and Judaism, such as belief in a formless deity, reincarnation and rejection of meat or red meat either completely or during religious times. While it seems certain that a number of distinct groups are intended by these names, the nature of these sects and the connections between them are less than clear. At least according to the Fihrist (see below), these groups seem all to have emerged from or developed in parallel with the "Sabian" followers of El-Hasaih; "Elkasaites" in particular may simply have been a blanket term for Mughtasila, Mandaeans, the original Sabians and even Manichaeans.

Sabians

The Quran makes several references to the Sabians, who are frequently thought to be Mandaeans. Sabians are counted among the Ahl al-Kitāb (People of the Book), and several hadith feature them. Arab sources of early Quranic times (7th century) also make some references to Sabians. Some scholars hold that the etymology of the root word 'Sabi'un' points to origins either in the Syriac or Mandaic word 'Sabian', and suggest that the Mandaean religion originated with Sabeans who came under the influence of early Hellenic Sabian missionaries, but preferred their own priesthood. The Sabians believed they "belong to the prophet Noah";[42] Similarly, the Mandaeans claim direct descent from Noah.

Early in the 9th century, a group of Hermeticists in the northern Mesopotamian city of Harran declared themselves Sabians when facing persecution; an Assyrian Christian writer said that the true 'Sabians' or Sabba lived in the marshes of lower Iraq. The Assyrian writer Theodore Bar Konai (in the Scholion, 792) described a "sect" of "Sabians", who were located in southern Mesopotamia.[43]

Al-Biruni (writing at the beginning of the 11th century) said that the 'real Sabians' were "the remnants of the Jewish tribes who remained in Babylonia when the other tribes left it for Jerusalem in the days of Cyrus and Artaxerxes. These remaining tribes ... adopted a system mixed-up of Magism and Judaism."[44]

Nasaraean

The Haran Gawaita uses the name Nasoraeans for the Mandaeans arriving from Jerusalem. Consequently, the Mandaeans have been connected with the Nasaraeans described by Epiphanius, a group within the Essenes.[45] Epiphanius says (29:6) that they existed before Christ. That is questioned by some, but others accept the pre-Christian origin of this group.

Elkesaites

The Elkesaites were a Judeo-Christian baptismal sect which seem to have been related, and possibly ancestral, to the Mandaeans (see Sabians). The members of this sect, like the Mandaeans, wore white and performed baptisms. They dwelt in east Judea and Assyria, whence the Mandaeans claim to have migrated to southern Mesopotamia, according to the Harran Gawaiṯā. In the Fihrist ("Book of Nations") of Arabic scholar Al-Nadim (c. 987), the Mogtasilah (Mughtasila, "self-ablutionists") are counted among the followers of El-Hasaih or Elkesaites. Mogtasilah may thus have been Al-Nadim's term for the Mandaeans, as the few details on rituals and habit are similar to Mandaeans ones. The Elkesaites seem to have prospered for a while, but ultimately splintered. They may have originated in a schism where they renounced the Torah, while the mainstream Sampsaeans held on to it (as Elchasai's followers did)—if so, this must have happened around the mid-late 1st millennium CE. However, it is not clear exactly which group he referred to, for by then the Elkesaite sects may have been at their most diverse. Some disappeared subsequently; for example, the Sampsaeans are not well attested in later sources. The Ginza Rba, one of the chief holy scriptures of the Mandaeans, appears to originate around the time of Elchasai or somewhat thereafter.

Manichaeans

According to the Fihrist of ibn al-Nadim, the Mesopotamian prophet Mani, the founder of Manichaeism, was brought up within the Elkesaite (Elcesaite or Elchasaite) sect, this being confirmed more recently by the Cologne Mani Codex. None of the Manichaean scriptures has survived in its entirety, and it seems that the remaining fragments have not been compared to the Ginza Rba. Mani later left the Elkasaites to found his own religion. In a comparative analysis, Mandaean scholar Säve-Söderberg indicated that Mani's Psalms of Thomas were closely related to Mandaean texts.[46] This would imply that Mani had access to Mandaean religious literature, or that both derived from the same source.

Dositheans

They are connected with the Samaritan group the Dositheans by Theodore Bar Kōnī in his Scholion.

Number of adherents

Official numbers estimate that the current population of Mandaeans numbers between 60,000 and 70,000 people. Their proportion in their native lands has collapsed because of the Iraq War, with most of the community relocating to nearby Iran, Syria, and Jordan.

In 2011, Al Arabiya put the number of hidden and unaccounted for Iranian Mandaeans in Iran as high as 60,000.[47] According to a 2009 article in The Holland Sentinel, the Mandaean community in Iran has also been dwindling, numbering between 5,000 and at most 10,000 people.

Of the Mandaeans tallied in official numbers, many have formed diaspora communities outside the Middle East, especially Australia, where some 10,000[48] now reside, mainly around Sydney, representing 15% of the total world Mandaean population.

Approximately 1,000 Iranian Mandaeans have emigrated to the United States since the US State Department in 2002 granted them protective refugee status, which was also later accorded to Iraqi Mandaeans in 2007. A community estimated at 2,500 members live in Worcester, Massachusetts, where they began settling in 2008. Most emigrated from Iraq.[49]

Mandaeism does not allow conversion, and the religious status of Mandaeans who marry outside the faith and their children is disputed.[40]

References

- Buckley, Jorunn Jacobsen (2002), The Mandaeans: ancient texts and modern people (PDF), Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780195153859

- Rudolph, Kurt (1978). Mandaeism. BRILL. p. 15. ISBN 9789004052529.

In some texts, however, it is said that Anoš and Manda ḏHayyē appeared in Usa together with Jesus Christ (Mšiha), and exposed him as a lying prophet. This tradition can be explained by an anti-Christian concept, which is also found in Mandaeism, but, according to several scholars, it contains scarcely any traditions of historical events. Because of the strong dualism in Mandaeism, between body and soul, great attention is paid to the "deliverance" of the soul

- The Light and the Dark: Dualism in ancient Iran, India, and China Petrus Danker John Williams – 1990 "Although it shows Jewish and Christian influences, Mandaeism was hostile to Judaism and Christianity. Mandaeans spoke an East-Aramaic language in which 'manda' means 'knowledge'; this already is sufficient proof of the connection of Mandaeism with the Gnosis...

- Häberl 2009, p. 1

- Edmondo, Lupieri (2004). "Friar of Ignatius of Jesus (Carlo Leonelli) and the First "Scholarly" Book on Mandaeaism (1652)". ARAM Periodical. 16 (Mandaeans and Manichaeans): 25–46. ISSN 0959-4213.

- "Mandaeanism | religion".

- Etudes mithriaques 1978 p545 Jacques Duchesne-Guillemin "The conviction of the leading Mandaean scholars – E. S. Drower, Kurt Rudolph, Rudolph Macuch – that Mandaeanism had a pre-Christian origin rests largely upon the subjective evaluation of parallels between Mandaean texts and the Gospel of John."

- Iraqi minority group needs U.S. attention Archived 2007-10-25 at the Wayback Machine, Kai Thaler, Yale Daily News, 9 March 2007.

- "Save the Gnostics" by Nathaniel Deutsch, 6 October 2007, New York Times.

- Iraq's Mandaeans 'face extinction', Angus Crawford, BBC, 4 March 2007.

- Foerster, Werner (1974). Gnosis: A Selection of Gnostic texts. 2. Oxford University Press. p. 126. ISBN 9780198264347.

- Lupieri, Edmundo (2001). The Mandaeans: The Last Gnostics. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 12. ISBN 9780802833501.

Siouffi was a Syrian Christian who, having received a European education, entered the French diplomatic corps.

- Häberl, Charles (2009). The Neo-Mandaic Dialect of Khorramshahr. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 18. ISBN 978-3447058742.

In 1873, the French vice-consul in Mosul, a Syrian Christian by the name of Nicholas Siouffi, sought Mandaean informants in Baghdad without success.

- Tavernier, J.-B. (1678). The Six Voyages of John Baptista Tavernier. Translated by Phillips, J. pp. 90–93.

- Angel Sáenz-Badillos, A History of the Hebrew Language. Cambridge University Press, 1993 (ISBN 978-0521556347), p. 36 et passim. (See also Biblical Hebrew phonology#Classification: "Hebrew also shares with the Canaanite languages ... assimilation of non-final /n/ to the following consonant.")

- Viret described deism as a heretical development of Italian Renaissance naturalism, resulting from misuse of the liberty conferred by the Reformation to criticise idolatry and superstition.Viret, Pierre (1564). Instruction Chrétienne en la doctrine de la foi et de l'Évangile (Christian teaching on the doctrine of faith and the Gospel). Viret wrote that a group of people believed, like the Jews and Turks, in a God of some kind - but regarded the doctrine of the evangelists and the apostles as a mere myth. Contrary to their own claim, he regarded them as atheists.

- Bayle, Pierre (1820). "Viret". Dictionnaire historique et critique (in French). 14 (Nouvelle ed.). Paris: Desoer. Retrieved 2017-11-23.

- "THE MANDAEANS: THEIR HISTORY, RELIGION AND MYTHOLOGY – Mandaean Associations Union – اتحاد الجمعيات المندائية".

- {{cite web|url=http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/mandaeans-1

- "The Mandaeans: True descendents of ancient Babylonians". Nineveh.com. Retrieved 2011-12-17.

- Eric Segelberg "Maşbūtā. Studies in the Ritual of the Mandæan Baptism, Uppsala, Sweden, 1958."

- Drower, Ethel Stephana (1960). The secret Adam, a study of Nasoraean gnosis (PDF). London UK: Clarendon Press. xvi. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- Lupieri (2002), pp. 38–41.

- "Contemporary Issues for the Mandaean Faith – Mandaean Associations Union – اتحاد الجمعيات المندائية".

- Drower, Ethel Stefana. The Mandaeans of Iraq and Iran. Oxford At The Clarendon Press, 1937.

- Rudolf, K. (1978). Mandaeism. Leiden: Brill.

- Lupieri (2002), pp. 39–40, n. 43.

- Lupieri (2002), p. 116.

- Aldihisi, Sabah (2013). The Story of Creation in the Mandaean Holy Book the Ginza Rba. https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/1444088/1/U591390.pdf: ProQuest LLC. p. 188. OCLC 1063456888.CS1 maint: location (link)

- "Ginzā, der Schatz [microform] oder das grosse Buch der Mandäer : Ginzā : Free Download & Streaming : Internet Archive". 2001-03-10. Retrieved 2011-12-17.

- Edwin Yamauchi (1982). "The Mandaeans: Gnostic Survivors". Eerdmans' Handbook to the World's Religions, Lion Publishing, Herts., England, page 110

- "The Ginza Rba – Mandaean Scriptures". The Gnostic Society Library. Retrieved 2011-12-17.

- Baker, Karen (September 28, 2017). The Mandaeans—Baptizers of Iraq and Iran. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 9781498246200 – via Google Books.

- "The Edinburgh Review". A. and C. Black. April 26, 1880 – via Google Books.

- Secunda, Shai, and Steven Fine. Secunda, Shai; Fine, Steven (2012-09-03). Shoshannat Yaakov. ISBN 978-9004235441. Brill, 2012.p345

- "Iraq: Old Sabaean-Mandean Community is Proud of Its Ancient Faith".

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AdQq4GkT5Ao

- Buckley, Jorunn Jacobsen. The Mandaeans: Ancient Texts and Modern People. Oxford University Press, 2002.p4

- Eric Segelberg, "The Ordination of the Mandæan tarmida and its Relation to Jewish and Early Christian Ordination Rites," (Studia patristica 10, 1970).

- Contrera, Russell (8 August 2009). "Saving the people, killing the faith". Holland Sentinel. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015.

- "THE MANDAEANS: THEIR HISTORY, RELIGION AND MYTHOLOGY – Mandaean Associations Union – اتحاد الجمعيات المندائية". www.mandaeanunion.com. Retrieved 2019-07-10.

- Khalil ‘ibn Ahmad (d. 786–787), who was in Basra before his death, wrote: "The Sabians believe they belong to the prophet Noah, they read Zaboor (see also Book of Psalms), and their religion looks like Christianity." He also states that "they worship the angels".

- Chwolsohn, Die Sabier, 1856, I, 112; II, 543, cited by Salmon.

- "Extracts from E. S. Drower, 'Mandaeans of Iraq and Iran'". Farvardyn.com. Archived from the original on 2011-12-04. Retrieved 2011-12-17.

- Drower, Ethel Stephana (1960). The secret Adam, a study of Nasoraean gnosis (PDF). London UK: Clarendon Press. xvi. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 March 2014., p. xiv.

- Torgny Säve-Söderberg, Studies in the Coptic Manichaean Psalm-book, Uppsala, 1949

- Ahmed Al-Sheati (6 December 2011). "Iran Mandaeans in exile following persecution". Al Arabiya News. Archived from the original on 31 July 2016. Retrieved 17 December 2011.

- "Meet the Mandaeans: Australian followers of John the Baptist celebrate new year – RN – ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation)".

- MacQuarrie, Brian (13 August 2016). "Embraced by Worcester, Iraq's persecuted Mandaean refugees now seek 'anchor'—their own temple". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

Bibliography

- Häberl, Charles G. (2009), The neo-Mandaic dialect of Khorramshahr, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3-447-05874-2

- Buckley, Jorunn Jacobsen. 2002. The Mandaeans: Ancient Texts and Modern People. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Buckley. J.J. "Mandaeans" in Encyclopædia Iranica

- Drower, Ethel Stefana. 2002. The Mandaeans of Iraq and Iran: Their Cults, Customs, Magic Legends, and Folklore (reprint). Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press.

- Lupieri, Edmondo. (Charles Hindley, trans.) 2002. The Mandaeans: The Last Gnostics. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company.

- "A Brief Note on the Mandaeans: Their History, Religion and Mythology," Mandaean Society in America.

- Newmarker, Chris, Associated Press article, "Faith under fire: Iraq war threatens extinction for ancient religious group" (headline in The Advocate of Stamford, Connecticut, page A12, 10 February 2007)

- Petermann, J. Heinrich. 2007 The Great Treasure of the Mandaeans (reprint of Thesaurus s. Liber Magni). Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press.

- Segelberg, Eric, 1958, Maşbūtā. Studies in the Ritual of the Mandæan Baptism. Uppsala

- Segelberg, Eric, 1970, "The Ordination of the Mandæan tarmida and its Relation to Jewish and Early Christian Ordination Rites," in Studia patristica 10.

- Eric Segelberg, Trāşa d-Tāga d-Śiślām Rabba. Studies in the rite called the Coronation of Śiślām Rabba. i: Zur Sprache und Literatur der Mandäer (Studia Mandaica 1.) Berlin & New York 1976.

- Segelberg, Eric, 1977, "Zidqa Brika and the Mandæan Problem. In Proceedings of the International Colloquium on Gnosticism. Ed. Geo Widengren and David Hellholm. Stockholm.

- Segelberg, Eric, 1978, "The pihta and mambuha Prayers. To the Question of the Liturgical Development amnong the Mandæans" in Gnosis. Festschrift für Hans Jonas. Göttingen.

- Segelberg, Eric, 1990, "Mandæan – Jewish – Christian. How does the Mandæan tradition relate to Jewish and Christian tradition? in: Segelberg, Gnostica Madaica Liturgica. (Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. Historia Religionum 11.) Uppsala 1990.

- Yamauchi, Edwin. 2004. Gnostic Ethics and Mandaean Origins (reprint). Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press.

External links

- Mandaean Association Union – The Mandaean Association Union is an international federation which strives for unification of Mandaeans around the globe. Information in English and Arabic.

- BBC: Iraq chaos threatens ancient faith

- BBC: Mandaeans – a threatened religion

- Shahāb Mirzā'i, Ablution of Mandaeans (Ghosl-e Sābe'in – غسل صابئين), in Persian, Jadid Online, 18 December 2008

- Audio slideshow (showing Iranian Mandaeans performing ablution on the banks of the Karun river in Ahvaz): (4 min 25 sec)

Mandaean scriptures

- Mandaean scriptures: Qolastā and Haran Gawaitha texts and fragments (note that the book titled Ginza Rba is not the Ginza Rba but is instead Qolastā, "The Canonical Prayerbook of the Mandaeans" as translated by E.S Drower).

- Gnostic John the Baptist: Selections from the Mandæan John-Book: This is the complete 1924 edition of G.R.S. Mead's classic study of the Mandæan John-Book, containing excerpts from the scripture itself (in The Gnosis Archive collection – www.gnosis.org).

- The Ginza Rba (1925 German translation by Mark Lidzbarski) at the Internet Archive

- The John-Book (Draša D-Iahia) – complete text in Mandaic and German translation (1905) by Mark Lidzbarski at the Internet Archive

- Mandaic liturgies – Mandaic text (in Hebrew transliteration) and German translation (1925) by Mark Lidzbarski at the Internet Archive

Books about Mandaeism available online

- Fragments of a Faith Forgotten by G. R. S. Mead a complete version (with old and new errors), contains information on Mani, Manichaeism, Elkasaites, Nasoraeans, Sabians and other "gnostic" groups. Published in 1901.

- Extracts from E. S. Drower, Mandaeans of Iraq and Iran, Leiden, 1962

- The Mandaeans of Iraq and Iran by Lady Drower, 1937 – the entire book