Sheffield Wednesday F.C.

Sheffield Wednesday Football Club is a professional association football club based in Sheffield, Yorkshire, England. The team competes in the Championship, the second tier of the English football league system. Formed in 1867 as an offshoot of The Wednesday Cricket Club (itself formed in 1820), they went by the name of the Wednesday Football Club until changing to their current name in 1929.

| |||

| Full name | Sheffield Wednesday Football Club | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Nickname(s) | The Owls | ||

| Short name | SWFC | ||

| Founded | 1867 as The Wednesday | ||

| Ground | Hillsborough Stadium | ||

| Capacity | 34,854[1][2][3] | ||

| Owner | Dejphon Chansiri | ||

| Manager | Garry Monk[4] | ||

| League | Championship | ||

| 2019–20 | Championship, 16th of 24 | ||

| Website | Club website | ||

|

| |||

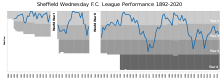

Wednesday is one of the oldest football clubs in the world of any code, and the third-oldest professional association football club in England.[lower-alpha 1] In 1868 its team won the Cromwell Cup, only the second tournament of its kind. They were founding members and inaugural champions of the Football Alliance in 1889, before joining The Football League three years later. In 1992, they became founder members of the Premier League. The team has spent most of its league history in English football's top flight, but they have not played at that level since being relegated in 2000.

The Owls, as they are nicknamed, have won four league titles, three FA Cups, one League Cup and one FA Community Shield. Wednesday have also competed in UEFA cup competitions on four occasions, reaching the quarter-finals of the Inter-Cities Fairs Cup in 1963. In 1991, they defeated Manchester United 1–0 in the Football League Cup Final as a tier 2 team. As of 2019 they remain the last team to win one of English football's major trophies while outside the top flight[5]

In the 19th century, they played their matches at several stadiums around central Sheffield, including Olive Grove and Bramall Lane. Since 1899, the club has played all its home matches at Hillsborough stadium, a near-40,000 capacity stadium in the north-west Sheffield suburb of Owlerton.[6][7] Wednesday’s biggest rivals are Sheffield United, with whom they contest the Steel City derby.

History

Early years (1867–1889)

Although no contemporary evidence has been found to support the claim, it is commonly believed that "The Wednesday Cricket Club" was formed in 1820.[8] Nevertheless, an 1842 article in Bell's Life magazine states the club was founded as far back as 1816.[8]

The club was so named because it was on Wednesdays that the founding members had their day off work. They were initially based at the New Ground in Darnall, and often went by the name of Darnall Wednesday, but also played at Hyde Park. In 1855 they were one of six clubs that helped build Bramall Lane, and held a wicket there for many years.[8]

Famous players to have represented the cricket club include Harry Sampson, who scored 162 on ice in 1841, Tom Marsden, who scored 227 for Sheffield & Leicester vs Nottingham in 1826, and George Ulyett, who represented the club in the first ever international test match before becoming one of only a select band of players who played for both sections of The Wednesday Club.

On the evening of Wednesday 4 September 1867, a meeting was held at the Adelphi Hotel to establish whether there was interest among the club's members to form a football club to keep the team together and fit during the winter months. The proposal proved very popular, with over 60 members signing up for the new team on the first night. They played their first match against The Mechanics on 19 October the same year, winning by three goals and four 'rouges' to nil.[9]

It soon became apparent that football would come to eclipse the cricketing side of the club in terms of popularity—the two sections went their separate ways in 1882 after a dispute over finances, and the cricket club ceased to exist in 1925. On 1 February 1868, Wednesday played their first competitive football match as they entered the Cromwell Cup, a one-off four-team competition for newly formed clubs. A week after their semi-final, they went on to win the cup, beating the Garrick club in the final after extra time, the only goal being scored in diminishing light at Bramall Lane. This was one of the first recorded instances of a match being settled by a "golden goal" although the term was not in use at the time.[10]

A key figure during the formative years of the football club was Charles Clegg, who joined the Wednesday in 1867. His relationship with the club lasted for the rest of his life and eventually led to his becoming the club's chairman. He also became president and chairman of the Football Association, and was known as the "Napoleon of Football".[11] Clegg played for England in the first-ever international match, against Scotland in November 1872, thereby completing a unique double for the club, who could lay claim to having a player in the first international games of cricket and football.

In 1876 Wednesday acquired Scot James Lang. Although he was not employed by the club, he was given a job by a member of the Sheffield Wednesday board that had no formal duties. He is now acknowledged as the first professional football player in England.[12] With Lang in their team the football club became one of the strongest in the region, a reputation that was cemented when they won the inaugural Sheffield FA Challenge Cup in 1877.

In 1880 the club entered the FA Cup for the first time, and they soon became one of the most respected sides in the country. But although they had had Lang on their books a decade earlier, the club officially remained staunchly amateur, and this stance almost cost the club its very existence.[8] By the middle of the decade, Wednesday's best players were leaving in their droves to join clubs who would pay them, and in January 1887 they lost 0–16 against Halliwell with just 10 players in their team. An emergency meeting was held, and the board members finally agreed to pay its players.[13]

Professional football, English Champions & FA Cup winners (1889–1939)

The move to professionalism took the club from Bramall Lane, which had taken a share of the ticket revenue, to the new Olive Grove.[14] In 1889 the club became founder members of the Football Alliance, of which they were the first champions in a season where they also reached the 1890 FA Cup Final, losing 6–1 to Blackburn Rovers at Kennington Oval, London. Despite finishing the following season bottom of the Alliance, they were eventually elected to the expanded Football League in 1892. They won the FA Cup for the first time in 1896, beating Wolverhampton Wanderers 2–1 at Crystal Palace.

Owing to an expansion of the local railway lines, the club was told that they would have to find a new ground for the 1899–1900 season.[13] After a difficult search the club finally bought some land in the village of Owlerton, which at the time was several miles outside the Sheffield city boundaries. Construction of a new stadium (now known as Hillsborough Stadium) was completed within months and the club was secured for the next century. In a strong decade, Wednesday won the League in the 1902–03 and 1903–04 seasons and the FA Cup again in 1907, beating Everton 2–1, again at Crystal Palace. When competitive football was suspended in 1915 because of the outbreak of World War One, the club participated in several regionalised war leagues, until 1919, when normal service was resumed.

They were relegated from the top flight for the first time in 1920, and did not return until 1926, and in the 1927–28 season they looked like going down again before securing a haul of 17 points from their last 10 matches to secure safety. Wednesday went on to win the League title the following season (1928–29), which started a run that saw the team finishing lower than third only once until 1936.[14] The period was topped off with the team winning the FA Cup for the third time in the club's history in 1935. When World War Two began, the club entered non-competitive war leagues, returning to the status quo in 1946.

The yo-yo years (1945–1989)

The 1950s saw Wednesday unable to consistently hold on to a position in the top flight and this period became known as the yo-yo years.[15] After being promoted in 1950 they were relegated three times, although each time they returned to the top flight by winning the Second Division the following season. The decade ended on a high note with the team finishing in the top half of the First Division for the first time since the Second World War.

In 1961, the club ran toe-to-toe with Tottenham Hotspur at the top of the table for the majority of the season – Wednesday became the first team to beat Spurs all season – before finally finishing in second place, which still (as of 2019) remains the club's highest post-war league finish. In 1966 the club reached its fifth FA Cup final, but they were beaten 2–3 by Everton, having led 2–0.

Off the field the club was embroiled in the British betting scandal of 1964 in which three of its players, Peter Swan, David Layne and Tony Kay, were accused of match fixing and betting against their own team in an away game at Ipswich Town. The three were subsequently convicted and, on release from prison, banned from football for life.[16] The three were reprieved in the early 1970s, with Swan and Layne returning to Hillsborough, and, though their careers were virtually over, Swan at least played some league games for The Owls.

Wednesday were relegated at the end of the 1969–70 season; this began the darkest period in the club's history, eventually culminating in the club dropping to the Third Division for the first time in its history, and in 1976 it almost fell into the Fourth Division. It was not until the appointment of Jack Charlton as manager in 1977 that the club started to climb back up the league pyramid. Charlton led the Owls back to the Second Division in 1980 before handing the reins to Howard Wilkinson, who took the club back into the top flight in 1984, after an absence of 14 years.

On 15 April 1989 the club's stadium was the scene of one of the worst sporting tragedies ever, at the FA Cup semi-final between Liverpool and Nottingham Forest, at which 96 Liverpool fans were fatally crushed in the Leppings Lane end of the stadium.[17] The tragedy resulted in many changes at Hillsborough and all other leading stadiums in England; it was required that all capacity should be of seats rather than of terracing for fans to stand,[18] and that perimeter fencing should be removed.[19]

Life at the top of the Premier League & European Football (1989–1995)

In Atkinson's first full season as manager, 1989–90, Sheffield Wednesday finished 18th in the First Division and were relegated on goal difference, despite the acquisition of the talented John Sheridan and the fact they had pulled towards mid-table at one stage of the season. They regained promotion at the first attempt but the real highlight of the season was a League Cup final victory over Atkinson's old club Manchester United. Midfielder Sheridan scored the only goal of the game, which delivered the club's first major trophy since their FA Cup success of 1935. Atkinson moved to Aston Villa shortly after promotion was achieved, and handed over the reins to 37-year-old striker Trevor Francis.

Wednesday finished third in the First Division at the end of the 1991–92 season, booking their place in the following season's UEFA Cup and becoming a founder member of the new FA Premier League.

1992–93 was one of the most eventful seasons in the history of Sheffield Wednesday football club. They finished seventh in the Premier League and reached the finals of both the FA Cup and the League Cup, but were on the losing side to Arsenal in both games, the FA Cup final going to a replay and only settled in the last minute of extra time. This prevented the Owls from making another appearance in European competition. Still, the 1992–93 season established Sheffield Wednesday as a top club. Midfielder Chris Waddle was voted Football Writers' Association Footballer of the Year, and the strike partnership of David Hirst and Mark Bright was one of the most feared in the country. Francis was unable to achieve any more success at the club, and two seasons later he was sacked. His successor was former Luton, Leicester and Tottenham manager David Pleat.

David Pleat's first season as Sheffield Wednesday manager was frustrating, as they finished 15th in the Premiership despite an expensively-assembled line-up which included the likes of Marc Degryse, Dejan Stefanovic and Darko Kovacevic – who all had disappointing and short-lived tenures at the club. An excellent start to the 1996–97 season saw the Owls top the Premiership after winning their first four games, and David Pleat was credited Manager of the Month for August 1996. But the club failed to mount a serious title challenge and they faded away to finish seventh in the final table. Pleat was sacked the following November with the club struggling at the wrong end of the Premiership, and Ron Atkinson briefly returned to steer the Owls clear of relegation.

At the end of the 1997–98 season, Ron Atkinson's short-term contract was not renewed and Sheffield Wednesday turned to the Barnsley boss Danny Wilson as their new manager after being given the backword by both Gerard Houllier and Walter Smith who joined Liverpool and Everton respectively. Wilson's first season at the helm brought a slight improvement as they finished 12th in the Premiership. An expensively assembled squad including Paolo Di Canio, Benito Carbone and Wim Jonk failed to live up to the massive wage bill the club was paying and things eventually came to a head when Italian firebrand Di Canio was sent off in a match against Arsenal and proceeded to push the referee on his way off. Danny Wilson was sacked the following March with relegation looking a certainty for the Hillsborough club, following a disastrous season where they had been hammered 8–0 by Newcastle United as early as September. His assistant Peter Shreeves took temporary charge but was unable to stave off relegation.

Modern highs and lows (1995–2012)

Wednesday couldn't keep the forward momentum going however, and by the turn of the new millennium again found itself on the brink of relegation – a 3–3 draw at Arsenal in May 2000 was enough to see the Owls tumble into the First Division. Having spent large sums building squads that were ultimately ineffective, the club's finances took a turn for the worse, and in 2003 they were relegated for a second time in four years, to the Second Division.[20]

The club spent two years in the third tier before returning the Championship, Paul Sturrock's side winning promotion via the play-offs in 2005.[21] Ultimately however, the club's perilous financial position ensured another drop to League 1 was not too far away – five years after the play-off win of 2005, the Owls were again relegated to League 1.[22]

Between July and November 2010, Sheffield Wednesday faced a series of winding up orders for unpaid tax and VAT bills, with the club's existence under severe threat.[23][24][25] It was not until 29 November 2010, when businessman Milan Mandarić agreed to buy out the old owners, that the club could move forward.

Fight back to the top (2012–present)

Mandarić appointed former Wednesday player Gary Megson as manager partway through the 2010–11 season, and while Megson only stayed in the job for a year, what was mostly his side won promotion back to the Championship in May 2012, under the stewardship of new manager Dave Jones.[26]

In 2014 the club was again taken over by a new owner, Thai businessman Dejphon Chansiri, purchasing the club from Milan Mandarić for £37.5m.[27] Chansiri stated his intention to win promotion back to the club for the 2017–18 season – the football club's 150th anniversary – and came close to achieving that goal a year head of schedule, with new coach Carlos Carvalhal leading the club into the end of season play-offs at the end of the 2015–16 season. Wednesday were beaten in the final by Hull City at Wembley. They made the play-offs again the following season, but lost on penalties to the eventually promoted Huddersfield Town in the semi final.[28]

The club were favourites to be promoted in the 2017/18 season, but injuries and poor results saw them drop to the lower half of the table. Carvalhal left by mutual consent in December 2017, and was replaced by Dutch manager Jos Luhukay a month later.[29][30] The team finished in an uneventful 15th place at the end of the season. Luhukay was sacked in December 2018 after a run of only 1 win in 10, which left the team 18th in the table.[31] He was replaced by former Aston Villa boss Steve Bruce who saw an upturn in form to finish 12th. However, Bruce controversially resigned in July 2019 to manage Newcastle United.[32]

On 6 September 2019, the club appointed former Birmingham City manager Garry Monk as the new manager, who achieved a 16th place finish in a season that was interrupted from March to June by the COVID-19 pandemic.[33][34][35]

Nickname, kits, crest and traditions

Nickname

In their early years, the club was nicknamed The Blades, a term used for any sporting team from the city of Sheffield, famous the world over for its cutlery and knives. That nickname has been retained by Wednesday's crosstown rivals, Sheffield United.

Although it is widely assumed that the club's nickname changed to The Owls in 1899 after the club's move to Owlerton, it was not until 1912, when Wednesday player George Robertson presented the club with an owl mascot, that the name took hold. A monkey mascot introduced some years earlier had not brought much luck.[36]

Kits

Since its founding the club has played their home games in blue and white shirts, traditionally in vertical stripes. However, this has not always been the case and there have been variations upon the theme. A monochrome photograph from 1874–75 shows the Wednesday team in plain dark shirts,[37] while the 1871 "Rules of the Sheffield Football Association" listed the Wednesday club colours as blue and white hoops.[14] A quartered blue and white design was used in 1887 and a blue shirt with white sleeves between 1965 and 1973.[38] Wednesday's socks have been predominantly black, blue or white throughout their history.

The club's away strip has changed regularly over the years. Traditionally, white was the second choice for many teams, including Wednesday, although the club has used a multitude of colours for its change strip over the years, including yellow, black, silver, green and orange.

Crest

Since 1912, the owl has become a theme that has run throughout the club. The original club crest was introduced in 1956[39] and consisted of a shield showing a traditionally drawn owl perched on a branch. The White Rose of York[40] was depicted below the branch alluding to the home county of Yorkshire and the sheaves of Sheffield (Sheaf field) were shown at either side of the owl's head. The club's Latin motto, Consilio et Animis, was displayed beneath the shield.[39] This translates into English as "By Wisdom and Courage".[41]

The crest was changed in 1970 to a minimalist version designed by a local art student, and this logo was used by the club, with variations, until 1995, when it was replaced by a similar design to the original crest. It again featured a traditionally drawn owl perched on a branch although the design of both had changed. The sheaves were replaced by a stylised SWFC logo that had been in use on club merchandise for several years prior to the introduction of the new crest. The Yorkshire Rose was moved to above the owl's head to make way for the words Sheffield Wednesday. The word Hillsborough was also curved around the top of the design. The club motto was absent on the new design. The crest was encased in a new shape of shield. This crest remained in use for only a few years, during which several versions were used with different colours, including a white crest with blue stripes down either side and the colouring of the detail inverted.[42]

In 1999, the minimalist version was brought back, albeit inside a crest, and with the addition of a copyright symbol in 2002.[39] In 2016, new owner Dejphon Chansiri again changed the club crest, opting for a similar design to the 1956 badge.

1956–1973

1973–1995

1995–1999

1999–2016

2016–

Mascots

Over the years Sheffield Wednesday have had several Owl themed matchday mascots. Originally it was Ozzie the Owl and later two further Owls, Baz & Ollie were added. All three were replaced in 2006 by Barney Owl, a similar looking owl but with more defined eyes to make it look cuter. Ozzie Owl was reintroduced as Wednesday's main mascot during the home game with Charlton Athletic on 17 January 2009. The current mascots are Ozzie and Barney Owl. In 2012, Ollie Owl also made his return to the scene, as the club announced him Mascot for the Owls work with children in the local community.

Stadium

Past stadiums

Originally, Wednesday played matches at Highfield, but moved several times before adopting a permanent ground. Other locations included Myrtle Road, Heeley and Hunter's Bar. Major matches were played at Sheaf House or Bramall Lane, before Sheffield United made it their home ground.[13] Sheffield Wednesday's first permanent home ground was at Olive Grove, a site near Queen's Road originally leased from the Duke of Norfolk. The first game at Olive Grove was a 4–4 draw with Blackburn Rovers on 12 September 1887. Extensions to the adjacent railway forced the club to move to their current ground in 1899.

Hillsborough Stadium

Since 1899 Wednesday have played their home games at Hillsborough Stadium in the Owlerton district of Sheffield. The stadium was originally named Owlerton Stadium but in 1914 Owlerton became part of the parliamentary constituency of Hillsborough and the ground took on its current name.[43] With 39,732 seats, Hillsborough has the third highest capacity of stadiums in Championship, and the 12th highest in England. The club intended to increase Hillsborough's capacity to 44,825 by 2012 and 50,000 by 2016 and make several other improvements in the process, but due to England's failed World Cup bid, this is now not the case.[44]

The stadium has hosted FIFA World Cup football (1966), The 1996 European Championships (Euro 96) and 27 FA Cup Semi-finals. The Kop at Hillsborough was re-opened in 1986 by Queen Elizabeth II and was once the largest covered stand of any football stadium in Europe.[45]

On 15 April 1989 at an FA Cup semi-final between Liverpool and Nottingham Forest, 96 Liverpool fans were crushed to death after the terraces at the Leppings Lane end of the ground became overcrowded, in what became known as the Hillsborough disaster. The following report concluded that the root cause of the disaster was the failure of local police to adequately manage the crowds.[46][47] A memorial to the victims of the disaster stands outside Hillsborough's South Stand, near the main entrance on Parkside Road. After many years of dispute about the facts, in June 2017 six men responsible for safety were charged with criminal offences including manslaughter and misconduct in public office.[48]

Support

The club's move to Owlerton in 1899 was a risky one, as it moved the club several miles away from the city centre, but its loyal followers continued to make the journey to the new ground, and the club has been one of the best supported in England ever since. However, official attendances were not taken at Football League games until the 1920s.

The club's highest average attendance over the course of a season was 42,530 in 1952–53, when gates across the country were at their highest. The lowest average attendance in the Owls' history came in 1978–79, when an average of just 10,643 fans turned out to watch their side.

In 1992, Wednesday were the fourth best supported team in the country, but although that ranking has come down since relegation from the Premier League in 2000, the club still has still enjoyed crowds of well over 20,000 since then, and was the best supported club outside the top flight in 2006.[49][50][51]

At the 2005 playoff final, Wednesday took over 39,000 fans to the Millennium Stadium.[52] In 2016, Sheffield Wednesday took over 38,000 fans to Wembley for a play-off final defeat by Hull City, selling substantially more seats than their counterparts many of whom boycotted the game. The Owls have managed to average 30000 at home in the last 60 years. The FA Cup Final seasons in 1965/6 30000 and 1966/7 31000 plus 32000 when coming League Championship Runners Up in 1960/61.

Sheffield Wednesday have had a large variety of fanzines over the years; examples include Just Another Wednesday, Out of the Blue, Spitting Feathers, Boddle, A View From The East Bank, Cheat! and War of the Monster Trucks, which acquired its name from the programme that Yorkshire Television elected to show instead of the celebrations after the 1991 League Cup victory over Manchester United.[53]

There are several online message boards dedicated to discussions on the club, including Owlstalk, OwlsOnline and OwlsMad.

Rivalry

Sheffield Wednesday's main rivals are city neighbours Sheffield United. Matches between these two clubs are nicknamed Steel City derbies, so called because of the steel industry for which the city of Sheffield is famous.

United were formed in 1889 by the committee at Bramall Lane, who had lost their biggest source of income – Wednesday – two years earlier over a dispute concerning pitch rent. As well as playing at Wednesday's former ground, United also took Wednesday's former nickname, the Blades, as their own. The first derby game took place on 15 December 1890, with Wednesday winning 2–1 at Olive Grove.

The 1993 FA Cup semi-final match which took place at Wembley on 3 April 1993. Initially, it was announced that the match was scheduled to take place at Elland Road but this was met with dismay by both sets of fans. After a re-think, the Football Association decided to switch venue to Wembley. A crowd of 75,365 supporters made the trip to London to watch Wednesday beat United 2–1 after extra time.

A survey conducted in 2019 revealed that, as well as Sheffield United, Wednesday fans consider fellow-Yorkshire sides Leeds United, Barnsley, Rotherham United and Doncaster Rovers as rivals.[54]

Honours

League

- First Division/Premier League (4)

- Second Division/Championship (5)

- Third Division/League One:

- Football Alliance (1)

- Winners: 1889–90

Cup

- FA Cup (3)

- Football League Cup (1)

- FA Community Shield (1)

- Sheriff of London Charity Shield (1):

- Winners: 1905

European record

| Season | Competition | Round | Opponent | Home | Away | Aggregate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1961–62 | Inter-Cities Fairs Cup | First round | 5–2 | 2–4 | 7–6 | |

| Second round | 4–0 | 0–1 | 4–1 | |||

| Quarter-final | 3–2 | 0–2 | 3–4 | |||

| 1963–64 | Inter-Cities Fairs Cup | First round | 4–1 | 4–1 | 8–2 | |

| Second round | 1–2 | 2–3 | 3–5 | |||

| 1992–93 | UEFA Cup | First round | 8–1 | 2–1 | 10–2 | |

| Second round | 2–2 | 1–3 | 3–5 | |||

| 1995–96 | UEFA Intertoto Cup | Group stage | N/A | 0–1 | N/A | |

| 3–2 | N/A | N/A | ||||

| N/A | 1–1 | N/A | ||||

| 3–1 | N/A | N/A |

Records

Wednesday's biggest recorded win was a 12–0 victory over Halliwell in the first round of the FA Cup on 18 January 1891. The biggest league win was against Birmingham City in Division 1 on 13 December 1930; Wednesday won 9–1. Both of these wins occurred at home.

The heaviest defeat was away from home against Aston Villa in a Division 1 match on 5 October 1912 which Wednesday lost 10–0.

The most goals scored by the club in a season was the 106 scored in the 1958–59 season. The club accumulated their highest league points total in the 2011–12 season when they racked up 93 points.

The highest home attendance was in the FA Cup fifth round on 17 February 1934. A total of 72,841 turned up to see a 2–2 draw with Manchester City. Unfortunately for Wednesday, they went on to lose the replay 2–0. Manchester City won the FA Cup that season.

The most capped Englishman to play for the club was goalkeeper Ron Springett who won 33 caps while at Sheffield Wednesday. Springett also held the overall record for most capped Sheffield Wednesday player until Nigel Worthington broke the record, eventually gaining a total of 50 caps for Northern Ireland whilst at the club.

The fastest sending off in British league football is held by Sheffield Wednesday goalkeeper Kevin Pressman – who was sent off after just 13 seconds for handling a shot from Wolverhampton Wanderers's Temuri Ketsbaia outside the area during the opening weekend of 2000.[55]

The fastest shot ever recorded in the Premier League was hit by David Hirst against Arsenal at Highbury in September 1996 – Hirst hit the bar with a shot clocked at 114 mph.

Former players and managers

Former players

A list of former players can be found at List of Sheffield Wednesday F.C. players.

Notable managers

Only managers with over 200 games in charge are included. For the complete list see List of Sheffield Wednesday F.C. managers.

| Name | Nat | From | To | Record | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | W | L | D | Win% | ||||

| Arthur Dickinson | 1 August 1891 | 31 May 1920 | 919 | 393 | 338 | 188 | 42.27% | |

| Robert Brown | 1 June 1920 | 1 December 1933 | 600 | 266 | 199 | 135 | 44.33% | |

| Eric Taylor | 1 April 1942 | 31 July 1958 | 539 | 196 | 215 | 128 | 36.36% | |

| Jack Charlton | 8 October 1977 | 27 May 1983 | 269 | 105 | 77 | 87 | 39.03% | |

| Howard Wilkinson | 24 June 1983 | 10 October 1988 | 255 | 114 | 73 | 68 | 44.70% | |

| Trevor Francis | 7 June 1991 | 20 May 1995 | 214 | 88 | 58 | 68 | 41.12% | |

Dickinson, who was in charge for 29 years, is Wednesday's longest-serving manager, and helped establish the club during the first two decades of the 20th century.

Brown succeeded Dickinson and remained in charge for 13 years; in 1930 he secured their most recent top division league title to date.

Taylor took over during the Second World War and remained in charge until 1958, but failed to win a major trophy, even though Wednesday were in the top flight for most of his reign.

Charlton took Wednesday out of the Third Division in 1980 and in his final season (1982–83) he took them to the semi-finals of the FA Cup.

Wilkinson succeeded Charlton in the summer of 1983 and was in charge for more than five years before he moved to Leeds United. His first season saw Wednesday gain promotion to the First Division after a 14-year exile. He guided them to a fifth-place finish in 1986, but Wednesday were unable to compete in the 1986–87 UEFA Cup due to the ban on English teams in European competitions due to the Heysel Disaster of 1985.

Francis took over as player-manager in June 1991 after Ron Atkinson (who had just guided them to Football League Cup glory and promotion to the First Division) departed to Aston Villa. He guided them to third place in the league in 1992, and earned them a UEFA Cup place. They finished seventh in the inaugural Premier League and were runners-up of the FA Cup and League Cup that year. He was sacked in 1995 after Wednesday finished 13th – their lowest standing in four years since winning promotion.

Players

First team squad

Note: Flags indicate national team as defined under FIFA eligibility rules. Players may hold more than one non-FIFA nationality.

|

|

Academy

First team staff

| Role | Name |

|---|---|

| Manager | |

| Assistant manager | |

| Coach | |

| Coach | |

| Goalkeeper coach | |

| Head of sports science and medicine | |

| Head of tactical analysis | |

| Head of performance | |

| Club doctor | |

| Head physio | |

| Physio | |

| Head of recruitment | |

| Recruitment analyst | |

| Performance analyst | |

| Sports scientist | |

| Masseur | |

| Masseur | |

| Head kitman | |

| Kitman |

Chairman and directors

| Role | Name |

|---|---|

| Chairman |

Notes

- Excluding clubs with informal or disputed foundation dates

References

- "Sheffield Wednesday Announce Capacity Increase ahead of Steel City Derby". Sheffield Star. 19 September 2017. Archived from the original on 22 October 2017. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- Wright, Oliver (23 May 2014). "Hillsborough: The changing face of a tragic stadium". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- "Ranking all 54 stadiums in Premier League history – where does Upton Park feature?". The Daily Telegraph. London: Telegraph Media Group. 10 May 2016. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- "Garry Monk confirmed as Wednesday boss". Sheffield Wednesday. Retrieved 6 September 2019.

- "Man United and Arsenal's SHOCK defeats: When teams outside the top flight reach cup finals". 24 January 2012.

- "Dave Jones to manage Sheffield Wednesday". BBC Sport. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- "Hillsborough". Sheffield Wednesday F.C. Archived from the original on 6 March 2009.

- Dickinson, Jason (2015). The Origins of Sheffield Wednesday. Amberley Publishing.

- Farnsworth, Keith (1995). Sheffield Football A History: Volume 1 1857–1861. Hallamshire Press. ISBN 1-874718-13-X.

- "The Cromwell Cup". Archived from the original on 28 July 2012. Retrieved 15 August 2006.

- "Players, Managers and Administrators". Sheffield Wednesday official website. Archived from the original on 2 May 2008. Retrieved 6 October 2008.

- "In the Beginning". FL Interactive Limited. Archived from the original on 8 August 2007. Retrieved 8 April 2009.

- Farnsworth, Keith (1982). Wednesday!. Sheffield City Libraries.

- Young, Percy M. (1962). Football in Sheffield. S. Paul.

- Adrian Bullock's Sheffield Wednesday Archive 1950s > yo-yo years.

- Broadbent, Rick (22 July 2006). "Swan still reduced to tears by the fix that came unstuck". The Times. London. Retrieved 8 April 2009.

- "BBC ON THIS DAY | 1989: Football fans crushed at Hillsborough". BBC News. 15 April 1945. Retrieved 31 January 2013.

- "Hillsborough Thatcher files to be released by June 2012". BBC. 30 November 2011. Retrieved 31 January 2013.

- Bolton, Andy (2 May 2012). "No.10 Hillsborough disaster | New Civil Engineer". Nce.co.uk. Retrieved 31 January 2013.

- "Sheffield Wednesday". London: Guardian Unlimited fanzines. 20 November 2001. Retrieved 6 October 2008.

- "Brighton 0–2 Sheff Wed". BBC. 17 April 2006. Retrieved 18 August 2006.

- Fletcher, Paul (2 May 2010). "Sheff Wed 2 – 2 Crystal Palace". BBC. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- "Sheffield Wednesday served winding up order by HMRC". BBC Sport. 23 July 2010. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- "Sheffield Wednesday broker deal to avoid administration". BBC Sport. 7 September 2010. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- "Sheffield Wednesday served with second winding-up order". BBC Sport. 9 November 2010. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- "Spirited End at Wednesday's Party". Wycombe Wanderers Trust. 5 May 2012. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- "Sheffield Wednesday: Dejphon Chansiri targets Premier League". BBC Sport. 2 March 2015.

- Sheffield Wednesday 1-1 Huddersfield Town, BBS Sport, 17 May 2017

- "Sheffield Wednesday part company with boss Carlos Carvalhal". BBC Sport. 24 December 2017.

- "Jos Luhukay: Sheffield Wednesday name new manager". BBC Sport. 5 January 2018.

- "Club statement".

- Jackson, Jamie (17 July 2019). "Sheffield Wednesday take legal advice after Newcastle appoint Steve Bruce". The Guardian.

- "Garry Monk: Sheffield Wednesday appoint ex-Birmingham City boss as manager". BBC Sport. 6 September 2019.

- https://www.thestar.co.uk/sport/football/sheffield-wednesday/anatomy-fall-assessing-turning-points-sheffield-wednesdays-disastrous-201920-campaign-2924491

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/sport/football/51867989

- Dickenson, Jason. One Hundred Years at Hillsborough.

- Spalding, Richard A. (1926). Romance of the Wednesday. Desert Island Books. ISBN 1-874287-17-1.

- Bickerton, Bob (1998). Club Colours. Hamlyn. ISBN 0-600-59542-0.

- "Sheffield Wednesday F.C. Crest & Club History". Footballcrests.com. 27 November 2003. Retrieved 31 January 2013.

- "1962 – Football Clubs and Badges card Sheffield Wednesday". Mike Duggan. Archived from the original on 27 December 2007. Retrieved 17 December 2007.

- "Facts and Figures". Sheffield Wednesday official website. Archived from the original on 17 April 2008. Retrieved 6 October 2008.

- "The Club Crest". A. Drake. Archived from the original on 18 October 2012. Retrieved 11 September 2006.

- "Hillsborough Stadium – About Hillsborough". Sheffield Wednesday Football Club. 26 June 2012. Archived from the original on 19 March 2015. Retrieved 9 May 2014.

- Hillsborough – a vision of the future Archived 20 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- "The ASD Lighting Kop". Sheffield Wednesday Football Club. Archived from the original on 8 August 2008. Retrieved 18 May 2008.

- "The Hillsborough Football Disaster". Hillsborough Justice Campaign. Retrieved 11 September 2006.

- "Information relating to the Hillsborough Stadium incident 15 April 1989". Health & Safety Executive. Retrieved 11 September 2006.

- Conn, David (28 June 2017). "Hillsborough disaster: six people, including David Duckenfield, charged". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- "Best Supporters". Sheffield Wednesday official website. 23 May 2006. Retrieved 6 October 2008.

- "2003–2004 Division Two average attendances". Sheffield Wednesday Football Club. Retrieved 8 April 2009.

- "2004–2005 League 1 average attendances". Sheffield Wednesday Football Club. Retrieved 8 April 2009.

- "Sturrock salutes fans". BBC News. 29 May 2005. Retrieved 18 August 2006.

- "About War of the Monster Trucks". The Guardian. London. 20 November 2001. Retrieved 6 October 2008.

- Swan, Rob (27 August 2019). "The top five rivals of English football's top 92 clubs revealed". GiveMeSport.

- "Pressman sent for earliest ever bath". BBC. 13 August 2000. Retrieved 27 October 2008.

Further reading

- Allen, Paul; Naylor, Douglas (2005). Flying with the Owls Crime Squad. London: John Blake. ISBN 1-84454-093-6.

- Brodie, Eric; Troilett, Allan. Jackie Robinson Story, The. ISBN 0-9547264-2-1.

- Dickinson, Jason (1999). One Hundred Years at Hillsborough, 2nd September 1899–1999. Sheffield: Hallamshire Press in association with Sheffield Wednesday Football Club. ISBN 1-874718-29-6.

- Dooley, Derek; Farnsworth, Keith (2000). Dooley!: The Autobiography of a Soccer Legend. Sheffield: Hallamshire. ISBN 1-874718-59-8.

- Farnsworth, Keith (1987). Sheffield Wednesday Football Club: A Complete Record, 1867–1987. Derby: Breedon. ISBN 0-907969-25-9.

- Farnsworth, Keith (1998). Wednesday: Every Day of the Week – An Oral History of the Owls. Derby: Breedon Books. ISBN 1-85983-131-1.

- Firth, John (2009). I Hate Football – A Sheffield Wednesday Fan's Memoir. Derbyshire: Peakpublish. ISBN 978-1-907219-02-3.

- Gordon, Daniel (2002). Blue-and-white-wizards: The Sheffield Wednesday Dream Team. Edinburgh: Mainstream. ISBN 1-84018-680-1.

- Hayes, Dean (1997). Hillsborough Encyclopaedia, The: A-Z of Sheffield Wednesday. Edinburgh: Mainstream Pub. ISBN 1-85158-960-0.

- Johnson, Nick (December 2003). Sheffield Wednesday 1867–1967. ISBN 0-7524-2720-2.

- Liversidge, Michael; Mackender, Gary. Sheffield Wednesday, Illustrating the Greats. ISBN 0-9547264-5-6.

- Waring, Peter (2004). Sheffield Wednesday Head to Head. Derby: Breedon. ISBN 1-85983-417-5.

External links

- Official site

- Owlstalk -Sheffield Wednesday News

- Sheffield Wednesday F.C. on BBC Sport: Club news – Recent results and fixtures

- Sheffield Wednesday play-off record