Magyarization

Magyarization (also Magyarisation, Hungarization, Hungarisation, Hungarianization, Hungarianisation), after "Magyar"—the autonym of Hungarians—was an assimilation or acculturation process by which non-Hungarian nationals came to adopt the Hungarian culture and language, either voluntarily or due to social pressure, often in the form of a coercive policy.[2]

.png)

In the era of national awakening, the Hungarian intellectuals transposed the concepts of the so-called "Political Nation" and Nation State from the Western European countries (especially the principles of the similarly highly multiethnic 18th century France), which included the idea of linguistic and cultural assimilation of minorities.[3]

The Hungarian Nationalities Law (1868) guaranteed that all citizens of the Kingdom of Hungary (then part of Dual Monarchy), whatever their nationality, constituted politically "a single nation, the indivisible, unitary Hungarian nation", and there could be no differentiation between them except in respect of the official usage of the current languages and then only insofar as necessitated by practical considerations.[4] In spite of the law, the use of minority languages was banished almost entirely from administration and even justice.[4] Defiance of, or appeals to, the Nationalities Law were met with derision or abuse.[4] The Hungarian language was overrepresented in the primary schools, and almost all secondary education was in Hungarian.[4]

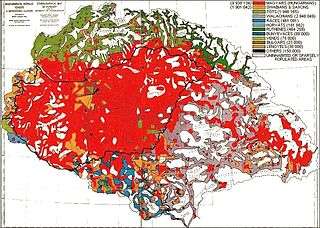

The Magyarization of the towns had proceeded at an astounding rate. Nearly all middle-class Jews and Germans and many middle-class Slovaks and Ruthenes had been Magyarized.[4] The percentage of the population with Hungarian as its mother tongue grew from 46.6% in 1880 to 54.5% in 1910. The 1910 census (and the earlier censuses) did not register ethnicity, but mother tongue (and religion) instead, based on which it is sometimes subject to criticism. However, most of the Magyarization happened in the centre of Hungary and among the middle classes, who had access to education; and much of it was the direct result of urbanization and industrialization. It had hardly touched the rural populations of the periphery, and linguistic frontiers had not shifted significantly from the line on which they had stabilized a century earlier.[4]

Use of the term

The term specifically applies to the policies that were enforced[5][6] in the Hungarian part of Austria-Hungary in the 19th century and early 20th century, especially after the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867,[4] and in particular after the rise in 1871 of the Count Menyhért Lónyay as head of the Hungarian government.[7]

When referring to personal and geographic names, Magyarization refers to the replacement of a non-Hungarian name with a Hungarian one.[8][9]

As is often the case with policies intended to forge or bolster national identity in a state, Magyarization was perceived by other ethnic groups such as the Romanians, Slovaks, Ruthenians (Rusyns or Ukrainians), Croats, Serbs, etc., as aggression or active discrimination, especially where they formed the majority of the population.[10][11]

In the Middle Ages

At the time of the Magyar conquest the Hungarian tribal alliance consisted of tribes of different ethnic backgrounds. There had to be a substantial Turkic element (e.g. Kabars).[12] The subjugated local population in the Hungarian settlement area (mainly the lowland territories) quickly merged with the Hungarians. In the period between the 9th and 13th centuries more groups of Turkic peoples migrated to Hungary (Pechenegs, Cumans etc.). Their past presence is visible in the occurrence of Turkic settlement names.

According to one of the theories, the ancestors of Székelys are Avars or Turkic Bulgars who were Magyarized in the Middle Ages.[13] Others argue that the Székely people descended from a Hungarian-speaking "Late Avar" population or from ethnic Hungarians who received special privileges and developed their own consciousness.

As a reward for their achievements in wars, noble titles were granted to some Romanian knezes. They entered Hungarian nobility, a part of them converting to Catholicism and their families being Magyarized: the Drágffy (Drăgoşteşti, Kendeffy (Cândeşti), Majláth (Mailat) or Jósika families were among the Romanian-origin Hungarian noble families.[14][15]

Historical context of the modern-times Magyarization

Between 1000–1784 and 1790–1844, Latin was the language of administration, legislation and schooling in Kingdom of Hungary.{Cf. http://hungarianparliament.com/history/} Joseph II (1780–90), a monarch influenced by the Enlightenment sought to centralize control of the empire and to rule it as an enlightened despot.[16] More than two and one half centuries following upon Martin Luther's "95 Theses" (1517) that in Central Europe, finally receptive of Protestantism, Emperor Joseph ll decreed that German replace Latin as the empire's official language.[16] In 1790, the change in administrative and next official language had signaled the narrowing terminus of the Holy Roman Empire. This centralization/homogenization struggle was not unique to Joseph II, it was a trend that one could observe all around Europe with the birth of the enlightened idea of Nation State.

Hungarians perceived Joseph's language reform as German cultural hegemony, and they reacted by insisting on the right to use their own tongue.[16] As a result, Hungarian lesser nobles sparked a renaissance of the Hungarian language and culture.[16] The lesser nobles questioned the loyalty of the magnates, of whom less than half were ethnic Magyars, and even those had become French- and German-speaking courtiers.[16]

The Magyarization policy actually took shape as early as the 1830s, when Hungarian started replacing Latin and German in education. Magyarization lacked any religious, racial or otherwise exclusionary component. Language was the only issue. The eagerness of the Hungarian government in its Magyarization efforts was comparable to that of tsarist Russification from the late 19th century.[17]

In the early 1840s Lajos Kossuth pleaded in the newspaper Pesti Hirlap for rapid Magyarization: "Let us hurry, let us hurry to Magyarize the Croats, the Romanians, and the Saxons, for otherwise we shall perish".[18] In 1842 he argued that Hungarian had to be the exclusive language in public life.[19] He also stated that in one country it is impossible to speak in a hundred different languages. There must be one language and in Hungary this must be Hungarian.[20] Zsigmond Kemény supported a multinational state led by Magyars, but he disapproved Kossuth's assimilatory ambitions.[21] István Széchenyi, who was more conciliatory toward other ethnic groups, criticized Kossuth for "pitting one nationality against another".[22] He promoted the Magyarization of non-Hungarians on the basis of the alleged "moral and intellectual supremacy" of the Hungarian population. But he felt that first Hungary itself must be made worthy of emulation if Magyarization was to succeed.[23] However the radical view on Magyarization of Kossuth gained more popular support than the moderate one of Széchenyi.[24] The slogan of the Magyarization campaign was One country – one language – one nation.[25]

On 28 July 1849, Hungarian Revolutionary Parliament acknowledged and enacted foremost[26][27] the ethnic and minority rights in the world,[28] but it was too late: to counter the successes of the Hungarian revolutionary army, the Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph asked for help from the "Gendarme of Europe", Tsar Nicholas I, whose Russian armies invaded Hungary. The army of the Russian Empire and the Austrian forces proved too powerful for the Hungarian army, and General Artúr Görgey surrendered in August 1849.

The Magyar national reawakening therefore triggered national revivals among the Slovak, Romanian, Serbian, and Croatian minorities within Hungary and Transylvania, who felt threatened by both German and Magyar cultural hegemony.[16] These national revivals later blossomed into the nationalist movements of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries that contributed to the empire's ultimate collapse.[16]

Magyarization in the Kingdom of Hungary

| Time | Total population of the Kingdom of Hungary | Percentage rate of Hungarians |

|---|---|---|

| 900 | ca. 800,000 | 55–71% |

| 1222 | ca. 2,000,000 | 70–80% |

| 1370 | 2,500,000 | 60–70% (including Croatia) |

| 1490 | ca. 3,500,000 | 80% |

| 1699 | ca. 3,500,000 | 50–55% |

| 1711 | 3,000,000 | 53% |

| 1790 | 8,525,480 | 37.7% |

| 1828 | 11,495,536 | 40–45% |

| 1846 | 12,033,399 | 40–45% |

| 1850 | 11,600,000 | 41.4% |

| 1880 | 13,749,603 | 46% |

| 1900 | 16,838,255 | 51.4% |

| 1910 | 18,264,533 | 54.5% (including ca. 5% Jews) |

The term Magyarization is used in regards to the national policies put into use by the government of the Kingdom of Hungary, which was part of the Habsburg Empire. The beginning of this process dates to the late 18th century[29] and was intensified after the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, which increased the power of the Hungarian government within the newly formed Austria-Hungary.[7][30] some of them had little desire to be declared a national minority like in other cultures. However, Jews in Hungary appreciated the emancipation in Hungary at a time when anti-semitic laws were still applied in Russia and Romania. Large minorities were concentrated in various regions of the kingdom, where they formed significant majorities. In Transylvania proper (1867 borders), the 1910 census finds 55.08% Romanian-speakers, 34.2% Hungarian-speakers, and 8.71% German-speakers. In the north of the Kingdom, Slovaks and Ruthenians formed an ethnic majority also, in the southern regions the majority were South Slavic Croats, Serbs and Slovenes and in the western regions the majority were Germans.[31] The process of Magyarization did not succeed in imposing the Hungarian language as the most used language in all territories in the Kingdom of Hungary. In fact the profoundly multinational character of historic Transylvania was reflected in the fact that during the fifty years of the dual monarchy, the spread of Hungarian as the second language remained limited.[32] In 1880, 5.7% of the non-Hungarian population, or 109,190 people, claimed to have a knowledge of the Hungarian language; the proportion rose to 11% (183,508) in 1900, and to 15.2% (266,863) in 1910. These figures reveal the reality of a bygone era, one in which millions of people could conduct their lives without speaking the state's official language.[33] The policies of Magyarization aimed to have a Hungarian language surname as a requirement for access to basic government services such as local administration, education, and justice.[34] Between 1850 and 1910 the ethnic Hungarian population increased by 106.7%, while the increase of other ethnic groups was far slower: Serbians and Croatians 38.2%, Romanians 31.4% and Slovaks 10.7%.[35]

The Magyarization of Budapest was rapid[36] and it implied not only the assimilation of the old inhabitants, but also the Magyarization of the immigrants. In the capital of Hungary, in 1850 56% of the residents were Germans and only 33% Hungarians, but in 1910 almost 90% declared themselves Magyars.[37] This evolution had benefic influence to the Hungarian culture and literature.[36]

According to census data, the Hungarian population of Transylvania increased from 24.9% in 1869 to 31.6% in 1910. In the same time, the percentage of Romanian population decreased from 59.0% to 53.8% and the percentage of German population decreased from 11.9% to 10.7%. Changes were more significant in cities with predominantly German and Romanian population. For example, the percentage of Hungarian population increased in Braşov from 13.4% in 1850 to 43.43% in 1910, meanwhile the Romanian population decreased from 40% to 28.71% and the German population from 40.8% to 26.41%.

State policy andatios

The first Hungarian government after the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, the 1867–1871 liberal government led by Count Gyula Andrássy and sustained by Ferenc Deák and his followers, passed the 1868 Nationality Act, that declared "all citizens of Hungary form, politically, one nation, the indivisible unitary Hungarian nation (nemzet), of which every citizen of the country, whatever his personal nationality (nemzetiség), is a member equal in rights." The Education Act, passed the same year, shared this view as the Magyars simply being primus inter pares ("first among equals"). At this time ethnic minorities "de jure" had a great deal of cultural and linguistic autonomy, including in education, religion, and local government.[40]

However, after education minister Baron József Eötvös died in 1871, and in Andrássy became imperial foreign minister, Deák withdrew from active politics and Menyhért Lónyay was appointed prime minister of Hungary. He became steadily more allied with the Magyar gentry, and the notion of a Hungarian political nation increasingly became one of a Magyar nation. "[A]ny political or social movement which challenged the hegemonic position of the Magyar ruling classes was liable to be repressed or charged with 'treason'..., 'libel' or 'incitement of national hatred'. This was to be the fate of various Slovak, South Slav [e.g. Serb], Romanian and Ruthene cultural societies and nationalist parties from 1876 onward..."[41] All of this only intensified after 1875, with the rise of Kálmán Tisza,[42] who as minister of the Interior had ordered the closing of Matica slovenská on 6 April 1875. Until 1890, Kálmán Tisza, when he served as prime minister, brought the Slovaks many other measures which prevented them from keeping pace with the progress of other European nations.[43]

For a long time, the number of non-Hungarians that lived in the Kingdom of Hungary was much larger than a number of ethnic Hungarians. According to the 1787 data, the population of the Kingdom of Hungary numbered 2,322,000 Hungarians (29%) and 5,681,000 non-Hungarians (71%). In 1809, the population numbered 3,000,000 Hungarians (30%) and 7,000,000 non-Hungarians (70%). An increasingly intense Magyarization policy was implemented after 1867.[44]

Although in Slovak, Romanian and Serbian history writing, administrative and often repressive Magyarization is usually singled out as the main factor accountable for the dramatic change in the ethnic composition of the Kingdom of Hungary in the 19th century, spontaneous assimilation was also an important factor. In this regard, it must be pointed out that large territories of central and southern Kingdom of Hungary lost their previous, predominantly Magyar population during the numerous wars fought by the Habsburg and Ottoman empires in the 16th and 17th centuries. These empty lands were repopulated, by administrative measures adopted by the Vienna Court especially during the 18th century, by Hungarians and Slovaks from the northern part of the Kingdom that avoided the devastation (see also Royal Hungary), Swabians, Serbs (Serbs were the majority group in most southern parts of the Pannonian Plain during Ottoman rule, i.e. before those Habsburg administrative measures), Croats and Romanians. Various ethnic groups lived side by side (this ethnic heterogeneity is preserved until today in certain parts of Vojvodina, Bačka and Banat). After 1867, Hungarian became the lingua franca on this territory in the interaction between ethnic communities, and individuals who were born in mixed marriages between two non-Magyars often grew a full-fledged allegiance to the Hungarian nation.[45] Of course since Latin was the official language until 1844 and the country was directly governed from Vienna (which excluded any large-scale governmental assimilation policy from the Hungarian side before the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, the factor of spontaneous assimilation should be given due weight in any analysis relating to the demographic tendencies of the Kingdom of Hungary in the 19th century.[46]

The other key factor in mass ethnic changes is that between 1880 and 1910 about 3 million[47] of Austro-Hungarians migrated to the United States alone. More than half of them were from Hungary (1.5 million+ or about 10% of the total population) alone.[48][49] Besides the 1.5 million that fled to the US (2/3 of them or about a million were ethnically non-Hungarians) mainly Romanians and Serbs had migrated to their newly established mother states in large numbers, like the Principality of Serbia or the Kingdom of Romania, who proclaimed their independence in 1878.[50] Amongst them were such noted people, like the early aviator Aurel Vlaicu (represented on the 50 Romanian lei banknote) or famous writer Liviu Rebreanu (first illegally in 1909, then legally in 1911) or Ion Ivanovici. Also many fled to Western Europe or other parts of the Americas.

Allegation of violent oppression

Many Slovak intellectuals and activists (such as Janko Kráľ) were imprisoned or even sentenced to death during the Hungarian Revolution of 1848.[51] One of the incidents that shocked European public opinion[52] was the Černová (Csernova) massacre in which 15 people were killed[52] and 52 injured in 1907. The massacre caused the Kingdom of Hungary to lose prestige in the eyes of the world when English historian R. W. Seton-Watson, Norwegian writer Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson and Russian writer Leo Tolstoy championed this cause.[53] The case being a proof for the violence of Magyarization is disputed, partly because the sergeant who ordered the shooting and all the shooters were ethnic Slovaks and partly because of the controversial figure of Andrej Hlinka.[54]

The writers who condemned forced Magyarization in printed publications were likely to be put in jail either on charges of treason or for incitement of national hatred.[55]

Education

The Hungarian secondary school is like a huge machine, at one end of which the Slovak youths are thrown in by the hundreds, and at the other end of which they come out as Magyars.

Schools funded by churches and communes had the right to provide education in minority languages. These church-funded schools, however, were mostly founded before 1867, that is, in different socio-political circumstances. In practice, the majority of students in commune-funded schools who were native speakers of minority languages were instructed exclusively in Hungarian.

Beginning with the 1879 Primary Education Act and the 1883 Secondary Education Act, the Hungarian state made more efforts to reduce the use of non-Magyar languages, in strong violation of the 1868 Nationalities Law.[55]

In about 61% of these schools the language used was exclusively Magyar, in about 20% it was mixed, and in the remainder some non-Magyar language was used.[58]

The number of minority-language schools was steadily decreasing: in the period between 1880 and 1913, when the number of Hungarian-only schools almost doubled, the number of minority language-schools almost halved.[59] Nonetheless, Transylvanian Romanians had more Romanian-language schools under the Austro-Hungarian Empire rule than there were in the Romanian Kingdom itself. Thus, for example, in 1880, in Austro-Hungarian Empire there were 2,756 schools teaching exclusively in the Romanian language, while in the Kingdom of Romania there were only 2,505 (The Romanian Kingdom gained its independence from the Ottoman Empire only two years before, in 1878).[60] The process of Magyarization culminated in 1907 with the lex Apponyi (named after education minister Albert Apponyi) which forced all primary school children to read, write and count in Hungarian for the first four years of their education. From 1909 religion also had to be taught in Hungarian.[61] "In 1902 there were in Hungary 18,729 elementary schools with 32,020 teachers, attended by 2,573,377 pupils, figures which compare favourably with those of 1877, when there were 15,486 schools with 20,717 teachers, attended by 1,559,636 pupils. In about 61% of these schools the language used was exclusively Magyar"[62] Approximately 600 Romanian villages were depleted of proper schooling due to the laws. As of 1917, 2,975 primary schools in Romania were closed as a result.[63]

The effect of Magyarization on the education system in Hungary was very significant, as can be seen from the official statistics submitted by the Hungarian government to the Paris Peace Conference (formally, all the Jewish people of the kingdom were considered as Hungarians, who had higher ratio in tertiary education than Christians):

By 1910 about 900,000 religious Jews made up approximately 5% of the population of Hungary and about 23% of Budapest's citizenry. They accounted for 20% of all general grammar school students, and 37% of all commercial scientific grammar school students, 31.9% of all engineering students, and 34.1% of all students in human faculties of the universities. Jews were accounted for 48.5% of all physicians,[64] and 49.4% of all lawyers/jurists in Hungary.[65]

| Major nationalities in Hungary | Rate of literacy in 1910 |

|---|---|

| German | 70.7 % |

| Hungarian | 67.1 % |

| Croatian | 62.5 % |

| Slovak | 58.1 % |

| Serbian | 51.3 % |

| Romanian | 28.2 % |

| Ruthenian | 22.2 % |

| Hungarian | Romanian | Slovak | German | Serbian | Ruthenian | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % of total population | 54.5% | 16.1% | 10.7% | 10.4% | 2.5% | 2.5% |

| Kindergartens | 2,219 | 4 | 1 | 18 | 22 | - |

| Elementary schools | 14,014 | 2,578 | 322 | 417 | n/a | 47 |

| Junior high schools | 652 | 4 | - | 6 | 3 | - |

| Science high schools | 33 | 1 | - | 2 | - | - |

| Teachers' colleges | 83 | 12 | - | 2 | 1 | - |

| Gymnasiums for boys | 172 | 5 | - | 7 | 1 | - |

| High schools for girls | 50 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Trade schools | 105 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Commercial schools | 65 | 1 | - | - | - | - |

Source:[67]

Election system

| Major nationalities | Ratio of nationalities | Ratio of franchise |

|---|---|---|

| Hungarians | 54.4 % | 56.2 % |

| Romanians | 16.1 % | 11.2 % |

| Slovaks | 10.7 % | 11,4 % |

| Germans | 10.4 % | 12,7 % |

| Ruthenians | 2,5 % | 2,9 % |

| Serbs | 2.5 % | 2.5 % |

| Croats | 1.1 % | 1,2% |

| Other smaller groups | 2,3 % |

The census system of the post-1867 Kingdom of Hungary was unfavourable to many of the of non-Hungarian nationality, because francishe was based on the income of the person. According to the 1874 election law, which remained unchanged until 1918, only the upper 5.9% to 6.5% of the whole population had voting rights.[69] That effectively excluded almost the whole of the peasantry and the working class from Hungarian political life. The percentage of those on low incomes was higher among other nationalities than among the Magyars, with the exception of Germans and Jews who were generally richer than Hungarians, thus proportionally they had a much higher ratio of voters than the Hungarians. From a Hungarian point of view, the structure of the settlement system was based on differences in earning potential and wages. The Hungarians and Germans were much more urbanised than Slovaks, Romanians and Serbs in the Kingdom of Hungary.

In 1900, nearly a third of the deputies were elected by fewer than 100 votes, and close to two-thirds were elected by fewer than 1000 votes.[70] Due to the economic reasons Transylvania had an even worse representation: the more Romanian a county was, the fewer voters it had. Out of the Transylvanian deputies sent to Budapest, 35 represented the 4 mostly Hungarian counties and the major towns (which together formed 20% of the population), whereas only 30 deputies represented the other 72% of the population, which was predominantly Romanian.[71][72]

In 1913, even the electorate that elected only one-third of the deputies had a non-proportional ethnic composition.[70] The Magyars who made up 54.5% of the population of the Kingdom of Hungary represented a 60.2% majority of the electorate. Ethnic Germans made up 10.4% of the population and 13.0% of the electorate. The participation of other ethnic groups was as follows: Slovaks (10.7% in population, 10.4% in the electorate), Romanians (16.1% in population, 9.9% in the electorate), Rusyns (2.5% in population, 1.7% in the electorate), Croats (1.1% in population, 1.0% in the electorate), Serbs (2.2% in population, 1.4% in the electorate), and others (2.2% in population, 1.4% in the electorate). There is no data about the voting rights of the Jewish people, because they were counted automatically as Hungarians, due to their Hungarian mother tongue. Jewish origin people were represented high ratio among the businessmen and intellectuals in the country, thus making the ratio of Hungarian voters much higher.

Officially, Hungarian electoral laws never contained any legal discrimination based on nationality or language. The high census suffrage was not uncommon in other European countries in the 1860s but later the countries of Western Europe gradually lowered and at last abolished their census suffrage. That never happened in the Kingdom of Hungary, although electoral reform was one of the main topics of political debates in the last decades before World War I.

Heavy dominance of ethnic minority elected liberal parties in the Hungarian Parliament

The Austro-Hungarian compromise and its supporting liberal parliamentary parties remained bitterly unpopular among the ethnic Hungarian voters, and the continuous successes of these pro-compromise liberal parties in the Hungarian parliamentary elections caused long lasting frustration among Hungarian voters. The ethnic minorities had the key role in the political maintenance of the compromise in Hungary, because they were able to vote the pro-compromise liberal parties into the position of the majority/ruling parties of the Hungarian parliament. The pro-compromise liberal parties were the most popular among ethnic minority voters, however i.e. the Slovak, Serb and Romanian minority parties remained unpopular among their own ethnic minority voters. The coalitions of Hungarian nationalist parties – which were supported by the overwhelming majority of ethnic Hungarian voters – always remained in the opposition, with the exception of the 1906–1910 period, where the Hungarian-supported nationalist parties were able to form a government.[73]

The Magyarization of personal names

The Hungarianization of names occoured mostly in bigger towns and cities, mostly in Budapest, in Hungarian majority regions like Southern Transdanubia, Danube–Tisza Interfluve (the territory between the Danube and Tisza rivers), and Tiszántúl, however the change of names in Upper Hungary (today mostly Slovakia) or Transylvania (now in Romania) remained a marginal phenomenon.[74]

Hungarian authorities put constant pressure upon all non-Hungarians to Magyarize their names and the ease with which this could be done gave rise to the nickname of Crown Magyars (the price of registration being one korona).[75] A private non-governmental civil organization "Central Society for Name Magyarization" (Központi Névmagyarositó Társaság) was founded in 1881 in Budapest. The aim of this private society was to provide advice and guidelines for those who wanted to Magyarize their surnames. Simon Telkes became the chairman of the society, and professed that "one can achieve being accepted as a true son of the nation by adopting a national name". The society began an advertising campaign in the newspapers and sent out circular letters. They also made a proposal to lower the fees for changing one's name. The proposal was accepted by the Parliament and the fee was lowered from 5 Forints to 50 Krajcárs. After this the name changes peaked in 1881 and 1882 (with 1261 and 1065 registered name changes), and continued in the following years at an average of 750–850 per year.[76] During the Bánffy administration there was another increase, reaching a maximum of 6,700 applications in 1897, mostly due to pressure from authorities and employers in the government sector. Statistics show that between 1881 and 1905 alone, 42,437 surnames were Magyarized, although this represented less than 0.5% of the total non-Hungarian population of the Kingdom of Hungary.[75] Voluntary Magyarization of German or Slavic-sounding surnames remained a typical phenomenon in Hungary during the whole course of the 20th century.

According to Hungarian statistics[77] and considering the huge number of assimilated persons between 1700 and 1944 (~3 million) only 340,000–350,000 names were Magyarised between 1815 and 1944; this happened mainly inside the Hungarian-speaking area. One Jewish name out of 17 was Magyarised, in comparison with other nationalities: one out of 139 (Catholic) -427 (Lutheran) for Germans and 170 (Catholic) -330 (Lutheran) for Slovaks.

The attempts to assimilate the Carpatho-Rusyns started in the late 18th century, but their intensity grew considerably after 1867. The agents of forced Magyarization endeavored to rewrite the history of the Carpatho-Rusyns with the purpose of subordinating them to Magyars by eliminating their own national and religious identity.[78] Carpatho-Rusyns were pressed to add Western Rite practices to their Eastern Christian traditions and efforts were made to replace the Slavonic liturgical language with Hungarian.[79]

The Magyarization of place names

Together with Magyarization of personal names and surnames, the exclusive use of the Hungarian forms of place names, instead of multilingual usage, was also common.[80] For those places that had not been known under Hungarian names in the past, new Hungarian names were invented and used in administration instead of the former original non-Hungarian names. Examples of places where non-Hungarian origin names were replaced with newly invented Hungarian names are: Szvidnik – Felsővízköz (in Slovak Svidník, now Slovakia), Sztarcsova – Tárcsó (in Serbian Starčevo, now Serbia), or Lyutta – Havasköz (in Ruthenian Lyuta, now Ukraine).[81]

There is a list of geographical names in the former Kingdom of Hungary, which includes place names of Slavic, Romanian or German origin that were replaced with newly invented Hungarian names between 1880 and 1918. On the first place the former official name used in Hungarian is given, on the second the new name and on the third place the name as it was restored after 1918 with the proper orthography of the given language.[81]

Migration

During the dualism era, there was an internal migration of segments of the ethnically non-Hungarian population to the Kingdom of Hungary's central predominantly Hungarian counties and to Budapest where they assimilated. The ratio of ethnically non-Hungarian population in the Kingdom was also dropping due to their overrepresentation among the migrants to foreign countries, mainly to the United States.[82] Hungarians, the largest ethnic group in the Kingdom representing 45.5% of the population in 1900, accounted for only 26.2% of the emigrants, while non-Hungarians (54.5%) accounted for 72% from 1901 to 1913.[83] The areas with the highest emigration were the northern mostly Slovak inhabited counties of Sáros, Szepes, Zemlén, and from Ung county where a substantial Rusyn population lived. In the next tier were some of the southern counties including Bács-Bodrog, Torontál, Temes, and Krassó-Szörény largely inhabited by Serbs, Romanians, and Germans, as well as the northern mostly Slovak counties of Árva and Gömör-Kishont, and the central Hungarian inhabited county of Veszprém. The reasons for emigration were mostly economic.[84] Additionally, some may have wanted to avoid Magyarization or the draft, but direct evidence of other than economic motivation among the emigrants themselves is limited.[85] The Kingdom's administration welcomed the development as yet another instrument of increasing the ratio of ethnic Hungarians at home.[86]

The Hungarian government made a contract with the English-owned Cunard Steamship Company for a direct passenger line from Rijeka to New York. Its purpose was to enable the government to increase the business transacted through their medium.[87]

By 1914, a total number of 3 million had emigrated,[88] of whom about 25% returned. This process of returning was halted by World War I and the partition of Austria-Hungary. The majority of the emigrants came from the most indigent social groups, especially from the agrarian sector. Magyarization did not cease after the collapse of Austria-Hungary but has continued within the borders of the post-WW-I Hungary throughout most of the 20th century and resulted in high decrease of numbers of ethnic Non-Hungarians.[89]

Jews

In the nineteenth century, the Neolog Jews were located mainly in the cities and larger towns. They arose in the environment of the latter period of the Austro-Hungarian Empire – generally a good period for upwardly mobile Jews, especially those of modernizing inclinations. In the Hungarian portion of the Empire, most Jews (nearly all Neologs and even most of the Orthodox) adopted the Hungarian language as their primary language and viewed themselves as "Magyars of the Jewish persuasion".[90] The Jewish minority which to the extent it is attracted to a secular culture is usually attracted to the secular culture in power, was inclined to gravitate toward the cultural orientation of Budapest. (The same factor prompted Prague Jews to adopt an Austrian cultural orientation, and at least some Vilna Jews to adopt a Russian orientation.)[91]

After the emancipation of Jews in 1867, the Jewish population of the Kingdom of Hungary (as well as the ascending German population)[92] actively embraced Magyarization, because they saw it as an opportunity for assimilation without conceding their religion. (We also have to point out that in the case of the Jewish people that process had been preceded by a process of Germanization[91] earlier performed by Habsburg rulers). Stephen Roth writes, "Hungarian Jews were opposed to Zionism because they hoped that somehow they could achieve equality with other Hungarian citizens, not just in law but in fact, and that they could be integrated into the country as Hungarian Israelites. The word 'Israelite' (Hungarian: Izraelita) denoted only religious affiliation and was free from the ethnic or national connotations usually attached to the term 'Jew'. Hungarian Jews attained remarkable achievements in business, culture and less frequently even in politics. By 1910 about 900,000 religious Jews made up approximately 5% of the population of Hungary and about 23% of Budapest's citizenry. Jews accounted for 54% of commercial business owners, 85% of financial institution directors and owners in banking, and 62% of all employees in commerce,[93] 20% of all general grammar school students, and 37% of all commercial scientific grammar school students, 31.9% of all engineering students, and 34.1% of all students in human faculties of the universities. Jews were accounted for 48.5% of all physicians,[64] and 49.4% of all lawyers/jurists in Hungary.[65] During the cabinet of pm. István Tisza three Jewish men were appointed as ministers. The first was Samu Hazai (Minister of War), János Harkányi (Minister of Trade) and János Teleszky (Minister of Finance).

While the Jewish population of the lands of the Dual Monarchy was about five percent, Jews made up nearly eighteen percent of the reserve officer corps.[94] Thanks to the modernity of the constitution and to the benevolence of emperor Franz Joseph, the Austrian Jews came to regard the era of Austria-Hungary as a golden era of their history.[95]

But even the most successful Jews were not fully accepted by the majority of the Magyars as one of their kind—as the events following the Nazi German invasion of the country in World War II so tragically demonstrated." [96]

However, in the 1930s and early 1940s Budapest was a safe haven for Slovak, German, and Austrian Jewish refugees[97] and a center of Hungarian Jewish cultural life.[97]

In 2006 the Company for Hungarian Jewish Minority failed to collect 1000 signatures for a petition to declare Hungarian Jews a minority, even though there are at least 100,000 Jews in the country. The official Hungarian Jewish religious organization, Mazsihisz, advised not to vote for the new status because they think that Jews identify themselves as a religious group, not as a 'national minority'. There was no real control throughout the process and non-Jewish people could also sign the petition.[98]

Notable dates

- 1844 – Hungarian is gradually introduced for all civil records (kept at local parishes until 1895). German became an official language again after the 1848 revolution, but the laws reverted in 1881 yet again. From 1836 to 1881, 14,000 families had their name Magyarized in the area of Banat alone.

- 1849 – Hungarian Parliament during the revolution of 1848 acknowledged and enacted foremost the ethnic and minority rights in the world.

- 1874 – All Slovak secondary schools (created in 1860) were closed. Also the Matica slovenská was closed down in April 1875. The building was taken over by the Hungarian government and the property of Matica slovenská, which according to the statutes belonged to the Slovak nation, was confiscated by the Prime Minister's office, with the justification that, according to Hungarian laws, there did not exist a Slovak nation.[43]

- 1874–1892 – Slovak children were being forcefully moved into "pure Magyar districts".[99][100][101] Between 1887 and 1888 about 500 Slovak orphans were transferred by FEMKE.[102]

- 1883 – The Upper Hungary Magyar Educational Society, FEMKE, was created. The society was founded to propagate Magyar values and Magyar education in Upper Hungary.[43]

- 1897 – The Bánffy law of the villages is ratified. According to this law, all officially used village names in the Hungarian Kingdom had to be in Hungarian language.

- 1898 – Simon Telkes publishes the book "How to Magyarize family names".

- 1907 – The Apponyi educational law made Hungarian a compulsory subject in all schools in the Kingdom of Hungary. This also extended to confessional and communal schools, which had the right to provide instruction in a minority language as well. "All pupils regardless of their native language must be able to express their thoughts in Hungarian both in spoken and in written form at the end of fourth grade [~ at the age of 10 or 11]"[59]

- 1907 – The Černová massacre in present-day northern Slovakia, a controversial event in which 15 people were killed during a clash between a group of gendarmes and local villagers.

Post-Trianon Hungary

A considerable number of other nationalities remained within the frontiers of the post-Trianon Hungary:

According to the 1920 census 10.4% of the population spoke one of the minority languages as their mother language:

- 551,212 German (6.9%)

- 141,882 Slovak (1.8%)

- 23,760 Romanian (0.3%)

- 36,858 Croatian (0.5%)

- 23,228 Bunjevac and Šokci (0.3%)

- 17,131 Serb (0.2%)

The number of bilingual people was much higher, for example

- 1,398,729 people spoke German (17%)

- 399,176 people spoke Slovak (5%)

- 179,928 people spoke Croatian (2.2%)

- 88,828 people spoke Romanian (1.1%).

Hungarian was spoken by 96% of the total population and was the mother language of 89%.

In interwar period, Hungary expanded its university system so the administrators could be produced to carry out the Magyarization of the lost territories for the case they were regained.[103] In this period the Roman Catholic clerics dwelled on Magyarization in the school system even more strongly than did the civil service.[104]

The percentage and the absolute number of all non-Hungarian nationalities decreased in the next decades, although the total population of the country increased. Bilingualism was also disappearing. The main reasons of this process were both spontaneous assimilation and the deliberate Magyarization policy of the state.[105] Minorities made up 8% of the total population in 1930 and 7% in 1941 (on the post-Trianon territory).

After World War II about 200,000 Germans were deported to Germany according to the decree of the Potsdam Conference. Under the forced exchange of population between Czechoslovakia and Hungary, approximately 73,000 Slovaks left Hungary.[106] After these population movements Hungary became an ethnically almost homogeneous country except the rapidly growing number of Romani people in the second half of the 20th century.

After the First Vienna Award which gave Carpathian Ruthenia to Hungary, a Magyarization campaign was started by the Hungarian government in order to remove Slavic nationalism from Catholic Churches and society. There were reported interferences in the Uzhorod (Ungvár) Greek Catholic seminary, and the Hungarian-language schools excluded all pro-Slavic students.[107]

According to Chris Hann, most of the Greek Catholics in Hungary are of Rusyn and Romanian origin, but they have been almost totally Magyarized.[108] While according to the Hungarian Catholic Lexicon, though originally, in the 17th century, the Greek Catholics in the Kingdom of Hungary were mostly composed of Rusyns and Romanians, they also had Polish and Hungarian members. Their number increased drastically in the 17–18th centuries, when during the conflict with Protestants many Hungarians joined the Greek Catholic Church, and so adopted the Byzantine Rite rather than the Latin. In the end of the 18th century, the Hungarian Greek Catholics themselves started to translate their rites to Hungarian and created a movement to create their own diocese.[109]

See also

References

- New Europe College, Universitatea din București: Nation and National Ideology: Past, Present and Prospects : Proceedings of the International Symposium Held at the New Europe College, Bucharest. p. 328-329, ISBN 9789739862493

- "page60" (PDF). umd.edu.

- Stefan Berger and Alexei Miller (2015). Nationalizing Empires. Central European University Press. p. 409. ISBN 9789633860168.

- "Hungary – Social and economic developments". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008. Retrieved 20 May 2008.

- Western civilization: ideas, politics & society. From the 1600s – Marvin Perry – Google Boeken. Books.google.com. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- Sixteen months of indecision: Slovak American viewpoints toward compatriots ... – Gregory C. Ference – Google Boeken. Books.google.com. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- Bideleux and Jeffries, 1998, p. 363.

- The policy of the Hungarian state concerning the Romanian church in ... – Mircea Păcurariu – Google Books. Books.google.co.uk. 1 January 1990. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- Google Translate. Translate.google.com. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- The policy of the Hungarian state concerning the Romanian church in ... – Mircea Păcurariu – Google Books. Books.google.co.uk. 1 January 1990. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- The Central European Observer – Joseph Hanč, F. Souček, Aleš Brož, Jaroslav Kraus, Stanislav V. Klíma – Google Books. Books.google.co.uk. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- Paul Lendvai, The Hungarians: A Thousand Years of Victory in Defeat, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 2003, p. 14

- Dennis P. Hupchick. Conflict and Chaos in Eastern Europe. Palgrave Macmillan, 1995. p.55.

- (Romanian) László Makkai . Colonizarea Transilvaniei (p.75)

- Răzvan Theodorescu. E o enormitate a afirma că ne-am născut ortodocşi (article in Historia magazine)

- A Country Study: Hungary – Hungary under the Habsburgs. Federal Research Division. Library of Congress. Retrieved 30 November 2008.

- The Finno-Ugric republics and the Russian state, by Rein Taagepera 1999. p. 84.

- Ioan Lupaș (1992). The Hungarian Policy of Magyarization. Romanian Cultural Foundation. p. 14.

- "The Hungarian Liberal Opposition's Approach to Nationalities and Social Reform". mek.oszk.hu. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- László Deme (1976). The radical left in the Hungarian revolution of 1848. East European quarterly.

- Matthew P. Fitzpatrick (2012). Liberal Imperialism in Europe. Palgrave Macmillan US. p. 97. ISBN 978-1-137-01997-4.

- Peter F. Sugar, Péter Hanák, Tibor Frank. A History of Hungary

- Robert Adolf Kann; Stanley B. Winters; Joseph Held (1975). Intellectual and Social Developments in the Habsburg Empire from Maria Theresa to World War I: Essays Dedicated to Robert A. Kann. East European Quarterly. ISBN 978-0-914710-04-2.

- John D Nagle; Alison Mahr (1999). Democracy and Democratization: Post-Communist Europe in Comparative Perspective. SAGE Publications. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-85702-623-1.

- Anton Špiesz; Ladislaus J. Bolchazy; Dusan Caplovic (2006). Illustrated Slovak History: A Struggle for Sovereignty in Central Europe. Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-86516-426-0.

- Mikulas Teich, Roy Porter (1993). The National Question in Europe in Historical Context. Cambridge University Press. p. 256. ISBN 9780521367134.

- Ferenc Glatz (1990). Etudes historiques hongroises 1990: Ethnicity and society in Hungary,+ Volume 2. Institute of History of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. p. 108. ISBN 9789638311689.

- Katus, László: A modern Magyarország születése. Magyarország története 1711–1848. Pécsi Történettudományért Kulturális Egyesület, 2010. p. 268.

- Pástor, Zoltán, Dejiny Slovenska: Vybrané kapitoly. Banská Bystrica: Univerzita Mateja Bela. 2000

- Michael Riff, The Face of Survival: Jewish Life in Eastern Europe Past and Present, Valentine Mitchell, London, 1992, ISBN 0-85303-220-3.

- Katus, László: A modern Magyarország születése. Magyarország története 1711–1848. Pécsi Történettudományért Kulturális Egyesület, 2010. p. 553.

- Katus, László: A modern Magyarország születése. Magyarország története 1711–1848. Pécsi Történettudományért Kulturális Egyesület, 2010. p. 558.

- Religious Denominations and Nationalities Archived 29 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Magyarization process. Genealogy.ro. 5 June 1904. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- "IGL – SS 2002 – ao. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Karl Vocelka – VO". univie.ac.at.

- John Lukacs. Budapest 1900: A Historical Portrait of a City and Its Culture (1994) p.102

- István Deák. Assimilation and nationalism in east central Europe during the last century of Habsburg rule, Russian and East European Studies Program, University of Pittsburgh, 1983 (p.11)

- Rogers Brubaker (2006). Nationalist Politics and Everyday Ethnicity in a Transylvanian Town. Princeton University Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-691-12834-4.

- Eagle Glassheim (2005). Noble Nationalists: The Transformation of the Bohemian Aristocracy. Harvard University Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-674-01889-1.

- Bideleux and Jeffries, 1998, pp. 362–363.

- Bideleux and Jeffries, 1998, pp. 363–364.

- Bideleux and Jeffries, 1998, p. 364.

- Kirschbaum, Stanislav J. (March 1995). A History of Slovakia: The Struggle for Survival. New York: Palgrave Macmillan; St. Martin's Press. p. a136 b139 c139. ISBN 978-0-312-10403-0. Archived from the original on 25 September 2008. Retrieved 2 August 2011.

- Bideleux and Jeffries, 1998, pp. 362–364.

- Ács, Zoltán: Nemzetiségek a történelmi Magyarországon. Kossuth, Budapest, 1986. p. 108.

- Katus, László: A modern Magyarország születése. Magyarország története 1711–1848. Pécsi Történettudományért Kulturális Egyesület, 2010. p. 220.

- Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Rogers Bruebaker: Nationalism Reframed, New York, Cambridge University Press, 1996.

- Yosi Goldshṭain, Joseph Goldstein: Jewish history in modern times

- Katus, László: A modern Magyarország születése. Magyarország története 1711–1848. Pécsi Történettudományért Kulturális Egyesület, 2010. p. 392.

- Encyklopédia spisovateľov Slovenska. Bratislava: Obzor, 1984.

- Holec, Roman (1997). Tragédia v Černovej a slovenská spoločnosť. Martin: Matica slovenská.

- Gregory Curtis Ference (1995). Sixteen Months of Indecision: Slovak American Viewpoints Toward Compatriots and the Homeland from 1914 to 1915 as Viewed by the Slovak Language Press in Pennsylvania. Susquehanna University Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-945636-59-5.

- Katus, László: A modern Magyarország születése. Magyarország története 1711–1848. Pécsi Történettudományért Kulturális Egyesület, 2010. p. 570.

- Robert Bideleux and Ian Jeffries, A History of Eastern Europe: Crisis and Change, Routledge, 1998, p. 366.

- Ference, Gregory Curtis (2000). Sixteen Months of Indecision: Slovak American Viewpoints Toward Compatriots and the Homeland from 1914 to 1915 As Viewed by the Slovak Language Press from Pennsylvania. Associated University Press. p. 31. ISBN 0-945636-59-8.

- Brown, James F. (2001). The Grooves of Change: Eastern Europe at the Turn of the Millennium. Duke University Press. pp. 56. ISBN 0-8223-2652-3.

- Hungary article of Encyclopedia Britannica 1911

- Romsics, Ignác. Magyarország története a huszadik században ("A History of Hungary in the 20th Century"), pp. 85–86.

- Raffay Ernő: A vajdaságoktól a birodalomig-Az újkori Románia története = From voivodates to the empire-History of modern Romania, JATE Kiadó, Szeged, 1989)

- Teich, Mikuláš; Dušan Kováč; Martin D. Brown (2011). Slovakia in History. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 31 August 2011.

- Members of the Royal Society, Editor: Hugh Chisholm (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica: a dictionary of arts, sciences, literature and general information, VOLUME: 13. Encyclopædia Britannica. p. 901.

- Stoica, Vasile (1919). The Roumanian Question: The Roumanians and their Lands. Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh Printing Company. p. 27.

- László Sebők (2012): The Jews in Hungary in the light of the numbers LINK:

- Victor Karady and Peter Tibor Nagy: The numerus clausus in Hungary, Page: 42 LINK:

- Robert B. Kaplan; Richard B. Baldauf (2005). Language Planning and Policy in Europe. Multilingual Matters. p. 56. ISBN 9781853598111.

- Z. Paclisanu, Hungary's struggle to annihilate its national minorities, Florida, 1985 pp. 89–92

- Andras Gerő (2014). Nationalitiesandthe Hungarian Parliament(1867-1918) (PDF). p. 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 May 2020.

- http://www-archiv.parlament.hu/fotitkar/angol/book_2011.pdf, pg. 21

- R. W. Seton-Watson, Corruption and reform in Hungary, London, 1911

- R. W. Seton-Watson, A history of the Roumanians, Cambridge, University Press, 1934, p. 403

- Georges Castellan, A history of the Romanians, Boulder, 1989, p. 146

- András Gerő (2014). Nationalities and the Hungarian Parliament (1867–1918).

- (in Hungarian) Kozma, István, A névmagyarosítások története. A családnév-változtatások Archived 18 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine, História (2000/05-06)

- R. W. Seton-Watson, A history of the Roumanians, Cambridge, University Press, 1934, p. 408

- "A Pallas nagy lexikona". www.elib.hu.

- (in Hungarian) Kozma, István, A névmagyarosítások története. A családnév-változtatások Archived 18 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine, História (2000/05-06)

- Marek Wojnar. Department of Central and Eastern Europe, Institute of Political Studies, Polish Academy of Sciences A minor ally or a minor enemy? The Hungarian issue in the political thought and activity of Ukrainian integral nationalists (until 1941)

- Oliver Herbel (2014). Turning to Tradition: Converts and the Making of an American Orthodox Church. OUP USA. pp. 29–30. ISBN 978-0-19-932495-8.

- Tsuḳerman, Mosheh (2002). Ethnizität, Moderne und Enttraditionalisierung. Wallstein Verlag. p. 92. ISBN 978-3-89244-520-3.

- Lelkes György: Magyar helységnév-azonosító szótár, Talma Könyvkiadó, Baja, 1998

- István Rácz, A paraszti migráció és politikai megítélése Magyarországon 1849–1914. Budapest: 1980. p. 185–187.

- Júlia Puskás, Kivándorló Magyarok az Egyesült Államokban, 1880–1914. Budapest: 1982.

- László Szarka, Szlovák nemzeti fejlõdés-magyar nemzetiségi politika 1867–1918. Bratislava: 1995.

- Aranka Terebessy Sápos, "Középső-Zemplén migrációs folyamata a dualizmus korában." Fórum Társadalomtudományi Szemle, III, 2001.

- László Szarka, A szlovákok története. Budapest: 1992.

- James Davenport Whelpey, The Problem of the Immigrant. London: 1905.

- Immigration push and pull factors, conditions of living and restrictive legistration Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, UFR d'ETUDES ANGLOPHONES, Paris

- Loránt Tilkovszky, A szlovákok történetéhez Magyarországon 1919–1945. Kormánybiztosi és más jelentések nemzetiségpolitikai céllal látogatott szlovák lakosságú településekről Hungaro – Bohemoslovaca 3. Budapest: 1989.

- Michael Riff, The Face of Survival: Jewish Life in Eastern Europe Past and Present, Valentine Mitchell, London, 1992, ISBN 0-85303-220-3.

- Mendelsohn, Ezra (1987). The Jews of East Central Europe Between the World Wars. Indiana University Press. p. 87. ISBN 0-253-20418-6.

- Erényi Tibor: A zsidók története Magyarországon, Változó Világ, Budapest, 1996

- "Hungary – Social Changes". Countrystudies.us. Archived from the original on 14 October 2012. Retrieved 19 November 2013.

- Rothenberg 1976, p. 128.

- David S. Wyman, Charles H. Rosenzveig: The World Reacts to the Holocaust. (page 474)

- Roth, Stephen. "Memories of Hungary", pp. 125–141 in Riff, Michael, The Face of Survival: Jewish Life in Eastern Europe Past and Present. Valentine Mitchell, London, 1992, ISBN 0-85303-220-3. p. 132.

- "Budapest". Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Archived from the original on 4 April 2003. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- Index/MTI (3 July 2006). "Nem lesz kisebbség a zsidóság". index.hu (in Hungarian). Retrieved 11 December 2018.

- Nationalities Papers – Google Knihy. Books.google.com. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- Oddo, Gilbert Lawrence (1960). Slovakia and its people. R. Speller.

Deportation of Slovak children.

- Slovaks in America: a Bicentennial study – Slovak American Bicentennial Editorial Board, Slovak League of America – Google Knihy. Books.google.com. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- Strhan, Milan; David P. Daniel. Slovakia and the Slovaks.

- George W. White (2000). Nationalism and Territory: Constructing Group Identity in Southeastern Europe. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-8476-9809-7.

- Joseph Rothschild (1974). East Central Europe between the two World Wars. University of Washington Press. p. 193.

- András Gerő; James Patterson; Enikő Koncz (1995). Modern Hungarian Society in the Making: The Unfinished Experience. Central European University Press. p. 214. ISBN 978-1-85866-024-0.

-

- Bobák, Ján (1996). Mad̕arská otázka v Česko-Slovensku, 1944–1948 [Hungarian Question in Czechoslovakia] (in Slovak). Matica slovenská. ISBN 978-80-7090-354-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Christopher Lawrence Zugger (2001). The Forgotten: Catholics of the Soviet Empire from Lenin through Stalin. Syracuse University Press. p. 378. ISBN 978-0-8156-0679-6.

- Hann, C. M. (ed.) The Postsocialist Religious Question. LIT Verlag Berlin-Hamburg-Münster, 2007, ISBN 3-8258-9904-7.

- Magyar Katolikus Lexikon (Hungarian Catholic Lexicon): Görögkatolikusok (Greek Catholics)

Sources

- Rothenberg, Gunther E. (1976), The Army of Francis Joseph, Purdue University Press

- Dr. Dimitrije Kirilović, Pomađarivanje u bivšoj Ugarskoj, Novi Sad – Srbinje, 2006 (reprint). Originally printed in Novi Sad in 1935.

- Dr. Dimitrije Kirilović, Asimilacioni uspesi Mađara u Bačkoj, Banatu i Baranji, Novi Sad – Srbinje, 2006 (reprint). Originally printed in Novi Sad in 1937 as Asimilacioni uspesi Mađara u Bačkoj, Banatu i Baranji – Prilog pitanju demađarizacije Vojvodine.

- Lazar Stipić, Istina o Mađarima, Novi Sad – Srbinje, 2004 (reprint). Originally printed in Subotica in 1929 as Istina o Madžarima.

- Dr. Fedor Nikić, Mađarski imperijalizam, Novi Sad – Srbinje, 2004 (reprint). Originally printed in Novi Sad in 1929.

- Borislav Jankulov, Pregled kolonizacije Vojvodine u XVIII i XIX veku, Novi Sad – Pančevo, 2003.

- Dimitrije Boarov, Politička istorija Vojvodine, Novi Sad, 2001.

- Robert Bideleux and Ian Jeffries, A History of Eastern Europe: Crisis and Change, Routledge, 1998. ISBN 0-415-16111-8 hardback, ISBN 0-415-16112-6 paper.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Magyarization. |

- Scotus Viator (pseudonym), Racial Problems in Hungary, London: Archibald and Constable (1908), reproduced in its entirety on line. See especially Magyarization of schools (as of 1906)

- Magyarization in Banat