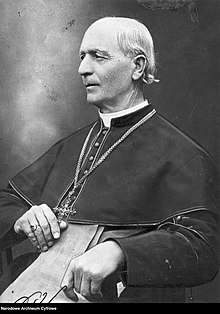

Andrej Hlinka

Andrej Hlinka (27 September 1864 – 16 August 1938) was a Slovak Catholic priest, journalist, banker and politician, one of the most important Slovak public activists in Czechoslovakia before Second World War. He was the leader of the Hlinka's Slovak People's Party (since 1913), papal chamberlain (since 1924), inducted papal protonotary (since 1927), member of the National Assembly of Czechoslovakia (the parliament) and chairman of the St. Vojtech Fellowship (a religious publication organization).

Andrej Hlinka | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 27 September 1864 |

| Died | 16 August 1938 (aged 73) |

| Political party | Catholic People's Party (until 1914) Slovak National Party Slovak People's Party (1914–1938) |

Life

Born in Černová (today part of the city of Ružomberok) in the Liptov County of the Kingdom of Hungary (present-day Slovakia), Hlinka graduated in theology from Spišská Kapitula and was ordained priest in 1889. He tried to improve the social status of his parishioners, fought against alcoholism and organized educational lectures and theater performances. He founded credit and food bank associations to help ordinary people and wrote a manual how to found further.

In his political views he was a strong defender of Catholic ethics against all secularizing tendencies connected with economic and political liberalism of the Kingdom of Hungary at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century. This was a similar position to that of the Hungarian Katolikus Néppárt (Catholic People's Party), led by Count Zichy, so Hlinka became an activist of this party. However, as the party disregarded Slovak demands Hlinka left and along with František Skyčák founded the Slovak People's Party.

He gained widespread popularity thanks to his social activities. In 1905, he was elected parson in Ružomberok against the wishes of his Hungarian bishop Alexander Párvy. In the Hungarian parliamentary elections of 1906, he supported Slovak candidate Vavro Šrobár and featured in favor of the Slovak national movement. His activities met with disapproval from the church hierarchy, which suspended him as a priest. On June 27, 1906, he was imprisoned and later convicted of sedition. While Hlinka was suspended and waited for admission to prison, Bishop Sándor Párvy ordered the consecration of a church in Černová, in the construction of which Hlinka had been instrumental, by Hungarian-speaking priests. This was met with protests and resistance from the local population and led to the Černová massacre, which brought international attention to the situation of the Slovak minority in the Kingdom of Hungary. In prison, Hlinka led the translation of the Old Testament into the Slovak language. His friends worked on his rehabilitation and Hlinka, who complained of his suspension to the Holy See, finally won the case against the bishop.

In 1907, he founded the Ľudová banka (People's Bank) and became the chairman of the board three years later.

The Slovak People's Party was separated from the Slovak National Party in 1913. Hlinka became party chairman and remained in this position for the rest of his life.

At the end of World War I, Hlinka significantly contributed to the creation of Czechoslovakia. On the confidential meeting of the Slovak National Party on 24 May 1918, he took a clear position and ended a prolonged discussion of undecided participants ("Thousand years old marriage with the Hungarians goes wrong. We have to divorce.") He became a member of the Slovak National Council and signed the Martin Declaration, which advocated a political union with the Czech nation. In the early period of Czechoslovakia, when a part of the Church hierarchy still preferred the Kingdom of Hungary, he intensively lobbied for the new state.

Hlinka quickly became disappointed by the undemocratic methods of his ex-colleague Vavro Šrobár (Minister-plenipotentiary for Slovakia affairs), some anti-religious actions and the unequal position of Slovakia. He complained to the Prime Minister and warned him that he would escalate these problems to the Paris peace conference. Hlinka believed that the problems could be solved on the basis of the Pittsburgh Agreement which promised autonomy of Slovakia within Czechoslovakia. On 28 August 1918, he really traveled to Paris under the influence of František Jehlička, whom Hlinka blindly trusted. Hlinka then distributed a memorandum about Slovakia to journalists and diplomats but failed to meet with key decision makers.[1] Hlinka, who arrived on a false passport, was arrested and hustled out of Paris by French police. This poorly timed and organized journey could have seriously harmed the interests of Czechoslovakia at the conference and damaged the image of Slovak autonomists. Except Hlinka, all participants stayed abroad and later worked for Hungarian irredentism.[2] Even the Slovak People's Party distanced itself from the actions of its leader. Hlinka was imprisoned and politically isolated and the ability of SĽS to act was limited.

Regardless of the mistake, Hlinka remained popular among voters of the Slovak People's Party. In April 1920, he was elected to the Czechoslovak Parliament and released from prison. Thereafter, he led the struggle for autonomy and for acknowledgment of an independent Slovak nation for almost 20 years. His motivation was based on religious and language grounds.[3] Hlinka accepted the idea of the common Czechoslovak political nation[4] but believed that centralism and ethnic Czechoslovakism threatened Slovak interests and their national and cultural identity ("We are for the common state of Czechs and Slovaks, but we are for the application of national individuality of both constituent nations."[5]) His party quickly became the most popular party in Slovakia with potential around 25%–35%.

Hlinka was known for his charisma, temperament, stubbornness and sharp tongue. The same qualities made him a difficult partner for negotiation. Hlinka regularly insulted his opponents and was often criticized for primitivism. The lack of higher education led him to an uncritical admiration of some of his questionable coworkers.[2] This was especially the case of Vojtech Tuka who several times undermined the interests of the party, but preserved Hlinka's trust regardless of the resistance of the HSLS.

At the end of his life, Hlinka was more a living symbol of the party than a real policymaker. In the 1930s, the party gradually moved closer to authoritative and undemocratic political ideas. Hlinka sympathized with authoritarian regimes like Salazar's Portugal or Dollfuss' Austria, both states in which catholic clericalism played a central role. During the final years of his life, his party was internally divided into two wings – the conservatives led by Catholic priest Jozef Tiso and the radicals, mostly young dissatisfied members. Hlinka tried to balance them and for tactical reasons supported them alternately. Hlinka, who never well understood foreign policy, was in favor of cooperation with Konrad Henlein and János Esterházy.[2] In February 1938, he refused closer cooperation with German minority parties, criticized the persecution of Christians in Germany and declared that Hilter is a "cultural beast",[6] despite his alleged sympathy with him.[7]

On June 5, 1938, Hlinka made a speech at a demonstration in Bratislava where he again raised a demand for Slovak autonomy. He signed the third proposal for the autonomy but died before he reached his goal. Only after the Munich Agreement when Czechoslovakia got into Nazi sphere of influence, loss of the Czech borderland and under the threat of territorial demands of Hungary, HSLS exploited the weakness of the state and declared autonomy on October 6, 1938, less than two months after Hlinka's death.

Legacy

During the first Slovak Republic, client state of Nazi Germany (1939–1945), Hlinka was considered by the regime as a national hero. Josef Tiso, his deputy and successor in Hlinka's Slovak People's Party, became the president of the fascist first Slovak Republic. Hlinka Guard, militia maintained by the Hlinka's Slovak People's Party created shortly before Hlinka's death, later participated in The Holocaust in Slovakia.

In Communist Czechoslovakia Hlinka was portrayed as a "clerofascist".

After the fall of Communism, Hlinka became again a respected person, mostly to nationalist sympathisers and to Christian democratic organisations, while the rest of current Slovak society seems mostly indifferent towards Hlinka's memory. Hlinka's image could be found on the Slovak 1000-crown banknote, before Slovakia's adoption of the Euro in 2009. A motion in the Parliament of Slovakia to proclaim him "father of the nation" nearly passed in September 2007.[8]

Now Andrej Hlinka, is mostly commemorated in his native Černová, where his House can be found. The exhibit is open to the public. Recently , the Mausoleum of Andrej Hlinka in Ružomberok was reopened.

References

- Vašs 2011, p. 127.

- Krajčovičová 2004.

- Vašs 2011, p. 128.

- Vašs 2011, p. 129.

- Vašs 2011, p. 133.

- a.s, Petit Press. "Letz: Hlinka nazval Hitlera pred nemeckými politikmi "kultúrnou beštiou"". domov.sme.sk.

- "Hlinka mal nevyberaný slovník, ale jeho pozitíva prevažujú". hn.hnonline.sk.

- Balogová, Beata (2007-12-17). "2007 was turbulent for the ruling coalition". The Slovak Spectator. Retrieved 2008-11-09.

Sources

- Krajčovičová, Natália (2004). "Andrej Hlinka v slovenskej politike" [Andrej Hlinka in the Slovak Policy]. Historická revue (in Slovak). Bratislava: Slovenský archeologický a historický ústav. ISSN 1335-6550. Archived from the original on 2011-09-12.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vašš, Martin (2011). Slovenská otázka v 1. ČSR (1918–1938) [The Slovak Question in the 1st Czechoslovakia (1918–1938)] (in Slovak). Martin: Matica slovenská. ISBN 978-80-8115-053-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Talks about the Slovak history and about Andrej Hlinka by Dr. Juraj Kuniak (Agens Banska Bystrica, 1991; ISBN 80-900504-0-9) translation into English by Dr. H. Reuvers, Maastricht, 2004.

- Newspaper clippings about Andrej Hlinka in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW