History of the Székely people

The history of the Székely people (a subgroup of the Hungarians in Romania) can be documented from the 12th century. According to medieval chronicles, the Székelys were descended from the Huns who settled in the Carpathian Basin in the 5th century. This theory was refuted by modern scholars, but no consensual view about the origin of the Székelys exists. They fought in the vanguard of the Hungarian army, implying that they had been a separate ethnic group, but their tongue does not show any trace of a language shift.

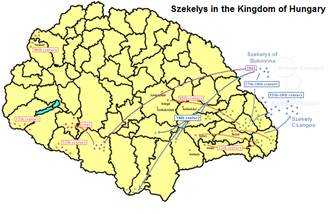

Scattered communities of light-armored Székely warriors lived in the Kingdom of Hungary, especially along the western frontier till the 14th century. Their migration to Transylvania began in the 11th or 12th century. They first settled in southern Transylvania, but they moved to present-day Székely Land after the arrival of the Transylvanian Saxons in the late 12th century. They were subjected to a royal official, the Count of the Székelys, from the 1220s. Their military role enabled them to preserve their privileged status. They did not pay tax and the kings of Hungary could not grant landed property in Székely Land. Their basic administrative units, known as seats from the 14th century, were headed by elected lieutenants and seat judges. They formed one of the "Three Nations of Transylvania" after a "brotherly union" was formed by the noblemen, Székelys and Saxons against the Transylvanian peasants in 1437.

The existence of three groups within the Székely society became evident in the 15th century. The commoners (or pixidarii) held small parcels of land and fought as foot soldiers. The wealthier primipili were mounted warriors. The high-ranking primores, who often also owned estates outside Székely Land, began to expand their authority over the commoners. Royal judges, appointed by the counts of the Székelys, supervised the elected officials of the seats from the 1460s. Being unable to serve in the army, the commoners lost their tax exemption in the 1550s. Many of them were reduced to serfdom after their rebellion was suppressed in 1562. The position of the royal judges was also strengthened, limiting the autonomy of the seats. On the other hand, the liberties of the Székely towns were confirmed. Although most Székelys remained Roman Catholic, significant groups adhered to Calvinism, Unitarianism or Sabbatarianism in the 16th century. The Székelys' privileges were restored in the 17th century, but many commoners (who did not want to serve in the army) voluntarily entered into serfdom. After Transylvania became part of the Habsburg Monarchy in the 1690s, the central government made attempts to limit the Székelys' liberties. Hundreds of villages were integrated into the Military Frontier after the Siculicidium (or Massacre of Székelys) at Madéfalva in 1764, but thousands of Székelys migrated to Moldavia to avoid military service. The Székely border guards lived under strict military rules.

Origins

Medieval chronicles unanimously stated that the Székelys were descended from the 5th-century Huns.[1] The Gesta Hungarorum and Simon of Kéza were the first to mention this information.[2][3] The Székelys' own tradition of their Hunnic origin is well-documented, but it is impossible to decide whether it is a genuine part of their folklore or an adoption of the medieval chroniclers' invention.[4] Most modern historians refute the Székelys' association with the Huns.[5]

Bálint Hóman was the first to propose that the Székelys were a Turkic group that joined the Magyars in the Pontic steppes.[6] György Györffy likewise said, the Székelys were obviously a separate ethnic group, because they fought in the vanguard of the Hungarian army.[6] Györffy and Gyula Kristó associated the Székelys with the Eskils (a tribe in Volga Bulgaria in the 9th century).[7] Kristó proposed that the Eskils was one of the three tribes of the Kabars who joined the Magyars after their secession from the Khazar Empire.[8] Gyula Németh and other linguists refuted the two peoples' identification, stating that their ethnonyms are not connected.[9]

According to most linguists and several historians, the Székelys did not change their language, because they speak the Hungarian language "without any trace of a Turkic substratum".[10][11] Linguist Lóránd Benkő asserted that the Székely dialects are closely connected to Hungarian dialects spoken along the borders of the medieval Kingdom of Hungary.[12] Consequently, he proposed that the Székelys were descended from the military guardians of the frontiers.[4] Their military role secured their special privileges, contributing to the development of their own consciousness.[13][4] Gyula László and Pál Engel proposed that the Székelys were descended from the (supposedly Hungarian-speaking) "Late Avar" (or Onogur) population of the Carpathian Basin.[14][10] The theory of the "double conquest" of the Carpathian Basin by the Hungarians has never been widely accepted.[11]

Kingdom of Hungary

Settlement in Székely Land

Royal charters indicate that scattered Székely groups lived in many regions of the Kingdom of Hungary.[15] A charter mentioned a military unit called Sceculzaz centurionatus ("Székelyszáz hundred") in Bihar County in 1217.[16][17] A 1256 diploma referred to a forest at Boleráz in Pozsony County (now in Slovakia) which was located "towards the Székelys".[15] The Székely warriors of Nagyváty in Baranya County were mentioned in 1272.[15] A 1314 royal charter stated that long time before Székelys had lived in an estate in Sopron County.[15] The Székelys of Sásvár in Ugocsa County (present-day Trosnik in Ukraine) were mentioned in 1323.[15]

The three main dialects of their tongue indicate that the Székelys' ancestors lived along the western frontiers.[12][18] The Székelys who now live along the rivers Nyárád and Kis-Küküllő (Niraj and Târnava Mică, respectively in Romania) speak a dialect similar to the tongue of the Hungarian communities near Pressburg (now Bratislava in Slovakia).[18] The dialect of Udvarhelyszék is closely related to the Hungarian variant spoken in Burgenland (now in Austria).[18] The third Hungarian variant of the Székely Land is similar to the Hungarian dialect of Baranya County.[18]

Székely and Pecheneg warriors fought side by side in the army of Stephen II of Hungary in the Battle of Olšava in 1116, according to the 14th-century Illuminated Chronicle.[17][19][20] The author of the chronicle blamed the Székelys and Pechenegs for the king's defeat, calling them as "the most wretched poltroons"[21] because of their unexpected retreat from the battlefield.[19] Györffy argues, thir flight from the battlefield was actually a feigned retreat which was an element of nomadic military tactics.[12] The same source recorded that the "wretched" Pechenges and the "worthless" Székelys "as usual went before the Hungarian army" in the Battle of the Fischa in 1146, evidencing that they fought in the vanguard.[17][19][22] The derogatory adjectives show that the Székelys were lightly armored archers.[23]

The Székelys were divided into six "kindreds";[note 1] and each "kindred" was composed of four "lineages".[24][25] All kindreds were documented in each district in Székely Land, implying that the kindreds had come into being by the time the Székelys settled in the territory.[24][25] The names of two kindreds[note 2] and five lineages[note 3] had their roots in Christian names.[24]

The exact date of the settlement of the Székelys in Transylvania cannot be determined.[26][27][28] Simon of Kéza wrote that the Székelys "acquired part of the country ... not in the plains of Pannonia but in the mountains, which they shared with the Vlachs, mingling with them, it is said".[29][2] Gyula Kristó says that the increase of the military role of the eastern borderlands caused their movement, because skirmishes along the western frontier became rare during the 12th century.[18] Pál Engel, Zoltán Kordé and Tudor Sălăgean argue that the kings of Hungary settled the Székelys in Transylvania in several stages.[26][27][28] Kristó adds, several Székely border guards voluntarily left for Transylvania, because the disintegration of the marchias (or border counties) threatened their freedom.[18]

The first groups allegedly settled in southern Transylvania,[28] along the rivers Kézd, Orbó, and Sebes (now Saschiz, Gârbova and Sebeș in Romania), because three administrative units in Székely Land—Kézdiszék, Orbaiszék and Sepsiszék—were named after these rivers.[30] Early 12th-century cemeteries unearthed at Szászsebes and Homoróddaróc (now Sebeș and Drăuşeni in Romania) evidence that the region had been inhabited before the arrival of the ancestors of the Transylvanian Saxons.[31] The Székelys who lived around Telegd in Bihar County (now Tileagd in Romania) also moved to Transylvania, because a group of the Székelys was known as the Székelys of Telegd in the 13th century.[32][16]

Joachim, Count of Hermannstadt, led an army of Saxons, Vlachs, Székelys and Pechenegs across the Carpathian Mountains to fight for Boril of Bulgaria around 1210, according to a royal charter issued in 1250.[33][34] The record suggests that the four ethnic groups were subjected to the Counts of Hermannstadt in the early 13th century.[35] William, Bishop of Transylvania, granted the tithe in Burzenland to the Teutonic Knights in 1213, but preserved the right to collect the tithe from the Székelys (and Hungarians) who would settle in the region.[35] The grant shows that significant Székely groups were on the move in the early 13th century.[35] The "land of the Székelys" was located to the north and northeast of the domain of the Knights in 1222.[36] Two years later, Andrew II granted the land of the Székelys of Sebes to the west of the Olt River to the Transylvanian Saxons, thus uniting the territories where Saxons had settled in southern Transylvania under the jurisdiction of the Count of Hermannstadt.[35]

The adoption of more than a dozen place names of Slavic origin[note 4] suggests that scattered Slavic-speaking communities inhabited present-day Székely Land at the time of the Székelys' arrival.[37] More than a dozen place names representing the oldest layer of Hungarian place names (personal names in the nominative case),[note 5] implies that other Hungarian-speaking groups had also preceded the Székelys.[38][39] The same conclusion can be drawn from the existence of the enclaves of Fehér County in Székely Land which survived until the 19th century.[38]

High Middle Ages

The Székelys were put under the jurisdiction of a new royal official, the Count of the Székelys, in the early 13th century.[40] The first known count, Bogomer, son of Szoboszló, was captured during a campaign that Béla, Duke of Transylvania, launched against Bulgaria in 1228.[41] The monarchs always appointed the counts from among the Hungarian noblemen.[42] The main administrative units of Székely Land were initially known as "terra" (or land).[43] The Diploma Andreanum contained the first reference to such a territory, mentioning terra Sebes ("the land of the Székelys of Sebes") in 1224.[43]

The Mongol invasion of the Kingdom of Hungary obviously caused less destruction in Székely Land than in other regions of Hungary.[44] Only two years after the withdrawal of the Mongols, Székely troops accompanied Lawrence, Voivode of Transylvania, to the Principality of Halych-Volhynia.[45] Székely warriors fought in the royal army against the Czechs and Austrians in the Battle of Kressenbrunn in 1260.[46] Stephen V of Hungary granted the royal domains along the Aranyos River (now Arieș in Romania) to the Székelys of Kézd, who established 18 villages in two decades.[45] The Mongols again invaded the Kingdom of Hungary in 1285.[47] The Székelys, Vlachs and Saxons resisted the invaders at the border, hindering their sudden attack.[48] The Székelys of Aranyos successfully defended Torockó (now Rimetea in Romania), forcing the invaders to set hundreds of captives free.[49]

The Székelys did not receive a royal diploma summarizing their liberties, but royal charters evidence that they had a special legal status.[50][51] The Székelys were not subjected to the authority of the voivodes and the ispáns (or heads) of the counties.[52] Their landed property could not be confiscated in favor of the royal treasury.[51] Neither could the monarchs grant estates in Székely Land.[51][53] Béla IV, who wanted to reward one Comes Vincent for his services, donated him an estate in Fehér County (outside Székely Land) in 1252.[54] Vincent was obviously the head of a Székely kindred, because four families[note 6] which descended from him gave the highest officials of Sepsiszék for centuries.[55] The Székelys prevented two noblemen from taking possession of an estate (Lok) that Charles I of Hungary had granted them in Csík in 1324.[53]

Instead of individuals, the community owned most lands in Székely Land.[56] Stephen V of Hungary had to instruct the universitas (or community) of the Székelys of Telegd in the early 1270s to receive two men into their society, allowing them to hold their estates "without borders, like the Székelys".[52] Parcels of the communal lands were time to time divided through "drawing arrows".[56] Communal property diminished through deforestation and the draining of marshlands, because such territories were seized by the individuals who had transformed the land.[57] The Székelys did not pay taxes, but the owners of landed property in Székely Land were required to serve in the royal army.[58] Daughters could only inherit landed property if they had no brothers.[51] A daughter who inherited an estate (known as a "boy-daughter") had to equip a warrior to fight on her behalf.[51] The Székelys gave 80 horses to Ladislaus IV of Hungary in the late 13th century.[52][51] Later, each Székely household was required to give an ox to the king on the occasions of his marriage and the birth of his eldest son.[59]

The Székelys' collective privileges strengthened in the 1290s.[53] Their representatives attained the general assembly that Andrew III of Hungary held at Gyulafehérvár (now Alba Iulia in Romania) in 1291.[60] Ehelleus Ákos, Vice-Voivode of Transylvania, granted the fortress on Székelykő at Torockó (now Piatra Secuiului in Romania) to the Székelys of Aranyos.[61] The Székelys were also represented at the Diet of Hungary in Pest in 1298.[53][62]

Taking advantage of the collapse of the royal authority, Ladislaus III Kán took control of Transylvania in the 1290s.[63] In 1296, he held a general assembly near Torda (now Turda in Romania) where the head of the Székelys of Aranyos were also present.[64] However, the Székelys did not support his sons' rebellion against Charles I of Hungary in the late 1310s.[65][64]

Late Middle Ages

The register of the papal tithe (the tenth part of each clergyman's revenues which was to be paid to the pope) between 1330 and 1337 is the first document to provide detailed information of the Roman Catholic parishes in Székely Land.[66] At least 150 parishes were mentioned in the document, showing that a church had been built in at least 80% of the villages (this ratio did not exceed 40% in other regions of the kingdom).[67] The parishes were divided among four archdeaneries[note 7] of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Transylvania.[68] The presence of Orthodox communities in this period has not been demonstrated.[69]

The Székely administrative units were known as széks (or seats) from the middle of the 14th century.[43] There were initially seven seats,[note 8] but Stibor of Stiboricz, Voivode of Transylvania, authorized the community of Miklósvár (now Micloșoara in Romania) to set up its own court of justice around 1395. The other seats only acknowledged the establishment of Miklósvárszék in 1459.[70] Each seat was headed by two elected officials, the lieutenant (maior exercitus) and the seat judge (iudex terrestris).[71][72] Theoretically, lieutenants were responsible for the military affairs and seat judges administered justice, but lieutenants also heard legal disputes.[71] Both seat judges and lieutenants heard disputes together with twelve jurors.[73]

Only Székelys who owned landed property known as "Székely inheritance" could be elected lieutenants or seat judges.[74] Such property almost always included a mill, increasing the revenues of its owner.[74] "Székely inheritances" were divided among the lineages, because the right to nominate and elect the officials of a seat moved from lineage to lineage in each year.[74] Consequently, members of the families who owned more than one "Székely inheritance" held the offices more frequently than others.[74]

Most Székely villages were named either after a lineage,[note 9] or after individuals,[note 10] known from 13th- and 14th-century charters.[75] Unlike the villages in the counties, the Székely villages preserved their autonomous status.[76][71] Ten families made up the basic administrative units (known as "tenth") of Székely Land.[71] Tenths supervised the regular division of the communal lands.[71]

Tenths were also responsible for the mobilization of the Székely warriors.[71] The Székelys' military obligations did not diminish in the 14th century.[71] Andrew Lackfi, Count of the Székelys, launched a campaign against the Golden Horde in 1345.[77] His victory enabled the expansion of Hungary across the Carpathian Mountains and contributed to the establishment of Moldavia.[77] Székely troops also participated in the campaigns of Louis I of Hungary in Italy, Lithuania, Serbia and Bulgaria.[78] Stephen Kanizsai commanded the Székely warriors in the Battle of Nicopolis,[78] which ended with the catastrophic defeat of the Christian army by the Ottomans in 1396.[77]

The Székelys primarily grew grain, onion, cabbage, hops, hemp and flax in the late 15th century.[79] Apple, pear, plum, walnut and hazelnut were the characteristic fruits of Székely Land.[79] The breeding of horses and cattle was also important segment of the local economy.[79] The Székelys also traded in skins of wolves, foxes, squirrels, martens and other wild animals.[79] The staple right of the Saxon town of Brassó hindered the development of the nearby Székely towns, especially that of Sepsiszentgyörgy (now Sfântu Gheorghe in Romania).[80] A royal charter recorded that a town was located in each seat in 1427, but most towns received privileges only during the following century.[80]

The existence of legally distinct groups of the Székely society was first documented in the early 15th century, but the origin of the three main groups can be traced back to the previous centuries.[81] Archaeologist Elek Benkő proposes that the tripartite Székely community (consisting of the high-ranking primores and primipili, and the commoners) preserved the features of the 11th-century Hungarian society.[82] The number of Székelys who could not secure their living increased due to the divisions of landed property through inheritance in the 15th century.[83] The poor entered the service of wealthy landowners.[84] On the other hand, Székelys who participated in military campaigns had the opportunity to receive land grants outside Székely Land.[85] Hungarian noblemen could seize a "Székely inheritance" through marriage or purchase.[86] Consequently, the wealthiest landowners held offices in both the seats and the counties.[87] For their estates in the counties were cultivated by dependent peasants, they also wanted to reduce the freedom of the commoners who worked on their estates in Székely Land.[83]

The Hungarian and Vlach peasants rose up in the Transylvanian counties in spring 1437.[88] Roland Lépes, Vice-Voivode of Transylvania, sought assistance from the Székelys and Saxons against them.[89] The representatives of the counties and the Székely and Saxon seats assembled at Bábolna (now Bobâlna in Romania).[90] They signed a "brotherly union" on 16 September, pledging that they would assist each other against all but the monarch.[90][91] After their united army defeated the peasants, they confirmed their alliance on 2 February 1438, which gave rise to the concept of the "Three Nations of Transylvania".[90][89]

Ottoman marauders made regulars incursions in Transylvania from the early 15th century.[92] Ottoman raiders routed an army of Székelys and Saxons at Brassó (now Brașov in Romania) in 1421; Ottoman, Wallachian and Moldavian troops made an incursion in Székely Land in 1432; Ottomans broke into Székely Land in 1438.[92][93] Sigismund, King of Hungary, had already in 1419 ordered that a third of the Transylvanian noblemen and a tenth of the peasants had to take up arms in case of an Ottoman invasion to assist the Székelys and Saxons in defending the borders.[92] The churches of Székely Land reflected a "frontier-guard mentality".[94] Churches in Csíkszék were fortified in the 15th century.[95] Frescoes on the walls of many churches represented King St Ladislaus's legendary fight with a "Cuman" warrior.[96] Episodes of the life of Saint Margaret of Antioch were also depicted on the walls of at least 8 churches.[97] Most frescoes were painted in Byzantine style.[97] The first references to Székely primary schools were recorded in the 15th century.[98] A schoolmaster lived in Hídvég (now Hăghig in Romania), and a teacher in Előpatak (now Vâlcele) in 1419.[98]

To secure the unified command of the borders, Vladislaus I of Hungary made John Hunyadi, Ban of Szörény, and Nicholas Újlaki, Ban of Macsó, the joint voivodes of Transylvania and counts of the Székelys in 1441.[99] Székely warriors accompanied Hunyadi during his campaigns in the Balkan Peninsula.[100] At Hunyadi's order, Nicholas Vízaknai, Vice-Voivode of Transylvania, and John Geréb of Vingárt, Castellan of Görgény (now Gurghiu in Romania), held an assembly for 24 Székely jurors in Marosvásárhely in 1451 to record customary laws.[100] This first known legislative assembly of the Székelys decreed that those who possessed landed property for 32 years acquired the title to it.[100]

Hunyadi's son, Matthias Corvinus, was elected king in 1458.[101] He confirmed the right of the Székelys of Kászon region to freely elect a lieutenant and a seat judge in 1462.[102] The offices of voivode of Transylvania and count of the Székelys were in practise united in the 1460s, because thereafter the kings always appointed the same noblemen to both offices.[103] To secure the military potential of the Székely community, Matthias ordered the collection of the liberties of the commoners in 1466.[83] The joint assembly of the Transylvanian noblemen and the Székely elders decreed that a Székely could not be forced to work on a landowner's estate.[83] The assembly also ruled that two-thirds of the jurors were to be elected from among the commoners.[83] Thereafter, the counts of the Székelys appointed a "royal judge" (or iudex regius) to supervise the administration of justice in each seat.[83]

Impoverished Székely commoners, however, could not fight as mounted warriors, forcing Matthias to revise his policy.[83] In 1473, he issued a new decree which distinguished the military obligations of the three main Székely groups.[83] The pimores, who owned an estate with a territory of at least three "bowshots", were thereafter required to equip three mounted warriors.[83] The primipili, who owned an estate with a territory of two "bowshots", continued to fight as mounted soldiers in person.[104] The Székely commoners, or pixidarii, were obliged to fight only as foot-soldiers.[57][104]

Stephen Báthory, Voivode of Transylvania and Count of the Székelys, made several attempts to reduce the autonomy of the seats in the early 1490s.[105] Accusing many primores of high treason, he confiscated their estates and forced Székely heiresses to marry his retainers.[106] At the Székelys' demand, Vladislaus II of Hungary replaced Báthory with Bartholomew Drágffy and Stephen Losonczy in 1493.[107] However, Drágffy, Losonczy and their successors neglected the administration of justice.[108] János Bögözi, Lieutenant of Udvarhelyszék, convoked the general assembly, which set up an appellate court in 1505.[108]

The Székelys' self-consciousness strengthened after their identifications as Huns was published in printed books in the late 15th century.[104] They regarded themselves as the representatives of the Huns' military virtues and began demanding the recognition of their privileged status.[104] After King Vladislaus II's only son, Louis, was born on 1 July 1506, royal officials came to Székely Land to collect the oxen which had traditionally been given to the monarchs on similar occasions.[104] However, the custom had been forgotten, because the kings had not fathered sons during the previous century.[109] Stating that they were noblemen (who did not pay taxes), the Székelys refused to give oxen to the royal officials.[104] The commander of the royal army, Pál Tomori, could only suppress the riot with the assistance of Saxon troops.[110] András Lázár convoked a new general assembly to Agyagfalva (now Lutiţa in Romania), which banished those who had conspired against the monarch and confiscated their landed property.[111]

The leader of the great uprising of the Hungarian peasants in 1514, György Dózsa, was of Székely origin, but the Székely commoners did not support the rebels.[110] John Zápolya, who had been count of the Székelys since 1510,[110] played a preeminent role in the victory of the noblemen over the peasants.[112] He also suppressed a revolt of the Székely commoners in 1519.[110] He ignored the special status of landed property in Székely Land and confiscated the rioters' estates in favor of the royal treasury.[110]

Disintegration

The Ottoman Sultan, Suleiman the Magnificent, inflicted a crushing defeat on the Hungarian army in the Battle of Mohács on 29 August 1526.[113] For Louis II of Hungary died in the battlefield, John Zápolya and Ferdinand of Habsburg laid claim to Hungary.[114] Both claimants were elected kings before the end of the year.[115] The Székelys supported John.[116] After he made an alliance with the Ottomans, the sultan instructed Petru Rareș, Voivode of Moldavia, to invade Transylvania through Székely Land to fight against Ferdinand's local supporters in 1529.[117]

In 1538, John recognized Ferdinand's right to reunite Hungary after his death.[118] However, John's supporters proclaimed his infant son, John Sigismund, king after he died in 1540.[119] Taking advantage of the new civil war, Suleiman occupied central Hungary, but allowed John Sigismund to retain the lands to the east of the Tisza River.[119][120] The minor king and his mother, Isabella Jagiellon, settled in Transylvania in 1542.[121]

Johannes Honter, the Lutheran priest of Brassó, sent preachers to Székely Land in the 1540s.[122] The wealthy Pál Daczó, who renovated the old church of Sepsiszentgyörgy (now Sfântu Gheorghe in Romania) "for the glory of God" in 1547, was the first Székely to certainly adopt Lutheranism.[123] Most villages in Miklósvárszék adhered to Lutheranism by the early 1550s,[123] but the majority of the Székelys remained Roman Catholic.[124] The Reformation also contributed to the development of education.[98] New schools were opened in dozens of settlements, including Székelykál and Gidófalva (now Căluşeri and Ghidfalău in Romania).[98] The high schools at Marosvásárhely and Székelyudvarhely became the first institutions of secondary education.[125]

Isabella renounced her son's realm in favor of Ferdinand of Habsburg in 1551.[126] Ferdinand made István Dobó and Ferenc Kendi voivodes of Transylvania.[127] The two voivodes confirmed the privileges of the Székelys in 1555.[128] John Sigismund and his mother returned to Transylvania in 1556.[129] During the following years, the Diet passed a series of decrees limiting the Székelys' liberties.[128] In 1557, the king was authorized to confiscate the estates of the Székelys who had been sentenced for high treason.[128] A year later, the Székely community was forced to pay a lump sum tax of 5,000 florins, only the primores and the primipili who were descended from 15th-century notables were exempted.[128] On the other hand, the queen declared that the Székely towns were required only to contribute to the yearly tribute payable to the sultans.[130] The towns were also exempted from the jurisdiction of the seats.[130]

After Melchior Balassa rebelled against John Sigismund, the primipili assembled at Székelyudvarhely in April 1562.[131] Thousands of commoners joined them, demanding the punishment of the wealthy Székelys whom they accused of unlawful collection of taxes and predatory lending.[132] The commoners attacked manors and defeated a royal army.[133] However, their army broke up without resistance after John Sigismund routed a small troop.[134] The Diet passed decrees to limit the commoners' freedom on 20 June 1562.[135] The court of appeal of Székely Land was dissolved, the commoners' right to be elected jurors was abolished and the royal judges became the sole leaders of the seats.[135] Two royal castles named Székelytámad ("Székely-assault") and Székelybánja ("Székely-regret") were erected in Székely Land.[136][137] The Székely commoners were not required to fight in the royal army, which deprived them from the legal basis of their freedom.[135] They were regarded the king's serfs, and many of them were forced to work at the building of royal castles or in the salt mines.[138] John Sigismund donated hundreds of Székely serfs to his supporters after 1566.[138]

Hungarian-speaking preachers promoted the theology of John Calvin from the late 1550s.[139] The synod of Marosvásárhely accepted Calvin's views of the Eucharist in 1559.[140] The creed was the first document of a Church assembly to be recorded in Hungarian.[141] In 1568, the Diet declared that all preachers could preach "according to his own understanding", which contributed to the spread of Anti-Trinitarian views.[142] Most Székely villages persisted with Roman Catholicism, but some Calvinist settlements joined the newly established Unitarian Church of Transylvania.[143][144]

Principality of Transylvania

Ottoman suzerainty

John Sigismund styled himself "prince of Transylvania" after the Treaty of Speyer in 1570.[129][145] Shortly after his death, armed Székely commoners marched to Gyulafehérvár to demand the restoration of their freedom from his successor, Stephen Báthory.[136][146] After Báthory refused them, hundreds of Székelys joined his opponent, Gáspár Bekes.[146] After Báthory defeated Bekes in 1575, more than 60 Székelys were executed or mutilated, and Báthory's supporters received Székely serfs.[146]

Anti-Trinitarian preachers who discouraged the adoration of Jesus appeared in Székely Land in the late 1570s.[147] Individual interpretation of the Bible became popular in the 1580s.[148] The idea of social equality in the Old Testament corresponded to the Székely traditions, which contributed to the spread of "Judaizing" views among the Székelys.[148] András Eőssi was the first leader of the Szekler Sabbatarians.[149] After the Diet ordered the persecution of radical Protestants in 1595, Benedek Mindszenti, Captain of Udvarhelyszék, forced hundreds of Sabbatarians to leave Transylvania in 1595.[150]

Stephen Báthory's successor, Sigismund Báthory, joined the Holy League that Pope Clement VIII organized against the Ottoman Empire.[151] After Sigismund promised the restoration of the Székelys' liberties if they took up arms against the Ottomans, more than 20,000 Székelys joined the royal army.[151][152] The united troops of Transylvania, Wallachia and Moldavia defeated the Ottomans in the Battle of Giurgiu.[151] Although the Székely serfs' contribution to the victory was undeniable, the landowners refused to grant them freedom.[153][152] After Sigismund also revoked his promise, the serfs rose up.[153] Stephen Bocskai crushed the revolt with extraordinary brutality during the "Bloody Carnival" of 1596.[154] Sigismund abdicated in favor of his cousin, Andrew Báthory, in March 1599.[152] Andrew's pro-Ottoman foreign policy threatened Michael the Brave, Voivode of Wallachia, who decided to invade Transylvania.[155] The Holy Roman Emperor, Rudolph II, who had laid claim to Transylvania, supported him.[156] After Michael presented a fake document in which Rudolph pledged that he would liberate the Székely serfs, thousand of Székelys joined Michael's army, but many Székely noblemen[note 11] remained faithful to Andrew.[157] Andrew was murdered by Székely peasants after Michael's victory in the Battle of Sellenberk.[158] Michael the Brave restored the Székely commoners' freedom, and they took revenge for the Bloody Carnival.[159]

Transylvania sank into political anarchy during the following years.[160] Rudolph's general, Giorgio Basta, expelled Michael from Transylvania and abolished the Székelys' liberties.[161] Moses Székely (the only prince of Székely origin) took up arms against Basta in 1603.[162] Most Székelys of Udvarhelyszék, Marosszék and Aranyosszék supported him, but the majority of the Székelys from other seats joined his opponent, Radu Șerban, Voivode of Wallachia.[154] János Petki, Captain of Udvarhelyszék, convoked the general assembly of the Székelys shortly after Stephen Bocskai had risen up against Rudolph in October 1604.[163] The Székely noblemen and commoners unanimously decided to support Bocskai if he was willing to confirm their liberties and to grant a general amnesty for the crimes committed during the anarchy.[163] Bocskai confirmed the Székelys' liberties in a charter on 16 February 1606.[164] Five days later, the delegates of the counties and the Székelys proclaimed him prince.[164]

The restoration of the Székely liberties included the Székely serfs' exemption from regular taxes.[165] For the serfs did not serve in the royal army, many Székely commoners entered into the service of wealthier landowners.[165] About 44% of the Székelys were serfs, according to the conscription in 1614.[166] Most serfs in Marosszék declared that they had voluntarily chosen serfdom to avoid poverty, starvation and military service.[165]

The detailed memoire of the Székely nobleman, Ferenc Mikó, is an important source of Transylvanian history between 1594 and 1613.[167] The development of large estates transformed the Székely society.[168] More than a hundred peasants worked on the domains of the wealthiest landowners.[169] They[note 12] renovated their old castles, or built new castles, strengthening them by walls and towers in the 17th century.[170] Lesser noblemen's manors were mostly decorated by wooden "Székely gates".[171]

The landowners invited colonists to settle in their lands.[172] The 1614 conscription mentioned peasants named "Oláh" (or Vlach) who had come from Moldavia, Wallachia or from the region of Fogaras and Karánsebes (now Făgăraș and Caransebeș in Romania).[172] The presence of colonists and serfs in the Székely villages required the adoption of new rules regarding the distribution of communal lands.[173] For instance, the community of Udvarfalva (now Curteni in Romania) allowed two serfs to seize parcels of the communal lands, stipulating that they had to leave the parcels if they came into conflict with the community.[174] The villages also regulated the use of streams and rivers, limiting tanning, dyeing and other activities that could pollute the water.[175] Hydro-energy of the swift rivers was also utilized: the Ottoman traveller, Evliya Çelebi, noticed hundreds of sawmills in Székelyudvarhely.[175] The mineral waters of Székely Land were famous in the whole principality.[176]

Gabriel Bethlen was the first prince to realize that the decrease of the number of free Székelys threatened the military potential of Transylvania.[177] He prohibited the Székelys to choose serfdom, ordered the redemption of hundreds of serfs and abolished the Székely serfs' tax exemption.[177][169] The latter measure persuaded many serfs to leave Székely Land.[177] The redemption of Székely serfs continued during the reign of George I Rákóczi, who also granted parcels of land to the liberated Székelys.[178] Rákóczi renounced the royal prerogarive of seizing and granting landed property in Székely Land in 1636.[179] Since the Sabbatarians supported Rákóczi's opponent, Moses Székely, the Diet ordered them to convert to one of the four official religions in 1638.[180] All who continued to celebrate the Sabbath on Saturday and failed to baptize their children were imprisoned.[181] Small Sabbatarian communities survived in the villages.[181]

George II Rákóczi broke into Poland without the sultan's authorization in 1656, provoking the invasion of Transylvania by the Ottomans.[182] After István Petki, Captain General of Csíkszék, did not accept the sultan's offer to claim the princely throne for himself, the Crimean Tatars pillaged Székely Land in 1661.[183][184] Michael I Apafi, who was elected prince at the Ottomans' order, recruited Székelys to defend his palace and fortresses.[185] He joined the Holye League against the Ottomans, recognizing that Transylvania was a land of the Holy Crown of Hungary in 1686.[186]

Military government and uprising

The army of Emperor Leopold I occupied Transylvania in late 1687.[187] He restored civil government in 1690, by issuing the Diploma Leopoldinum which confirmed the privileges of the Three Nations.[188][189] However, five years later, the imperial army again occupied the principality.[190] The new government increased the taxes and strengthened the position of the Roman Catholic Church, which stirred up discontent.[191][192] The increase of the taxes especially aggrieved the Székely villages, but the commander of the imperial army, Jean-Louis Rabutin de Bussy, suppressed all riots, imprisoning many Székelys.[193]

Francis II Rákóczi (a descendant of the Rákóczi princes of Transylvania) became the leader of the opposition against Leopold.[194] After taking control of Upper Hungary (now Slovakia) and large territories to the east of the Tisza in autumn 1703, he sent letters to the Three Nations (and also to the Romanians), urging them to support his war for independence.[193] The Székelys of Háromszék and Csíkszék were among the first to join him.[195] Rákóczi's supporters took control of Székely Land by early 1704.[195]

The Diet proclaimed Rákóczi prince,[196] but he could not enter Transylvania after the imperial army defeated his supporters in the Battle of Zsibó on 11 November 1705.[197] Székely Land was put under military administration and hundreds of Székelys left the principality.[198] The authorities limited free movement and began collecting all weapons.[198] The Székely soldiers returned under the command of Lőrinc Pekry in summer 1706.[198] Rákóczi, who was again elected prince, confirmed the Székelys' privileges in 1707.[198]

Leopold's successor, Joseph I, promised a general amnesty to those who would capitulate.[199] After Rákóczi left Hungary for Poland to seek assistance, the representatives of the rebels signed the Treaty of Szatmár in 1711, acknowledging the rule of the Habsburgs.[200][201] The Székely Kelemen Mikes was one of the few noblemen who followed Rákóczi into exile.[198] Mikes's Letters from Turkey demonstrate both his education in France and his Transylvanian heritage.[202]

Towards absolutism

The integration of Transylvania into the Habsburg Monarhcy accelerated after the Treaty of Szatmár.[203] The Gubernium (which was composed of 12 members appointed by the monarchs) became the supreme body of administration, but the most important decisions were made in Vienna.[204] The Diet enacted the decisions of the Gubernium without opposition.[205] The command of the imperial and local troops was unified in 1713.[203][204] Appeals against the decisions of the seat courts were heard at the Royal Table.[206] Since the monarchs supported the ideas of Counter-Reformation, many Székely noble families[note 13] converted to Catholicism.[207] The Unitarians and Sabbatarians were especially exposed to persecution in the 1720s.[203] The Diet was last summoned in 1761.[208]

Around 20% of the Transylvanian population perished because of a plague between 1717 and 1720.[209] Migration of serfs to Moldavia and Wallachia continued, but most migrants returned to Transylvania.[210] The Székely commoners and primipili made attempts to regain their tax exempt status, but their movements were suppressed.[207] Their largest rebellion broke out after Adolf Nikolaus Buccow, the military commander, decided to introduce the system of the Military Frontier in Székely Land in 1762, without consulting with the Diet or the seats.[211]

Buccow ordered the conscription of the commoners and primipili to set up new border guard troops, appointing German officers to complete the task.[211] Referring to their traditional privileges, most Székelys declared that they would only serve under the command of their own officers.[212] However, some commoners were ready to accept the new system and the imperial officials also promised freedom to the serfs who joined the new army.[210] They turned against those who resisted, attacking their houses and villages.[213]

Queen Maria Theresa appointed a new official, József Siskovics, to complete the organization of the Military Frontier.[213] Siskovics sent 10–20 soldiers to each villages, declaring that he would confiscated the landed property of those who resisted.[214] Most Székelys in Gyergyó yielded, but the men from Madéfalva (now Siculeni in Romania) and the nearby villages fled to the mountains.[214] After Siskovics ordered the expulsion of their wives and children from their houses, more than 2,700 armed Székelys came to Madéfalva from Háromszék and Csíkszék.[215] The imperial army attacked the village, slaughtering more than 200 Székelys on 7 January 1764.[215]

The Siculicidium (or Massacre of Székelys) at Madéfalva broke the Székelys' resistance.[213] The organization of the Székely border guard was completed before the end of March.[213] Two infantry regiments were set up in Csíkszék and Háromszék, and one hussar regiment in Csíkszék, Háromszék and Aranyosszék.[216] Romanian peasants from Aranyosszék made up more than a fifth of the hussar regiment.[216] Thousands of Székelys fled to Moldavia instead of joining the army.[215]

Grand Principality of Transylvania

Enlightment and absolutism

Maria Theresa declared Transylvania to be a grand principality on 2 November 1765.[217] The partial integration of Székely Land in the Military Frontier divided the society into a military and a civil part.[216] In the Military Frontier, most commoners and primipili joined the regiments.[218] In addition to the defence of the frontier, the border guards were obliged to chase robbers and smugglers.[219] The military commanders supervised the election of the magistrates, which diminished the autonomy of the Székely villages.[213] Many aspects of everyday life were also controlled by the officers: the border guards could only marry with the consent of their commanders and the officers were authorized to ban smoking and dancing.[220]

More than 44% of the inhabitants of Székely Land were commoners and primipili in the late 1760s, but the ratio of serfs and landless cotters exceeded 38%.[221] The settlement of Romanian peasants in Csíkszék, Háromszék and Aranyosszék contributed to the increase of their number.[221] Romani (or Gypsy) cotters were also mentioned in the 1760s.[221] Many of them were employed as blacksmiths and musicians in the noblemen's manors.[222] To regulate the obligations of the peasantry, the Gubernium issued a decree (the so-called Certain Points) in 1769, prescribing that they were to work four or three days a week on the estates of the noblemen.[220] Nevertheless, the peasants in Székely Land enjoyed more freedom than the serfs in the counties.[223] For instance, Székely serfs run taverns and butcheries together with the noblemen, while it was the noblemen's monopoly in the counties.[223]

The ideas of Enlightenment spread in Transylvania from the 1770s.[224] The polymath József Benkő (who was a Calvinist priest) wrote a trilingual botanical dictionary and a manual of caves.[225] He also promoted tobaccoo growing and the use of sumac in the leather industry.[225]

Maria Theresa's son and successor, Joseph II, wanted to transform the Habsburg Monarchy into a unitary state.[226] He abolished the seats and divided Transylvania into eleven counties in 1784.[227] He made German the official language of the central government and the towns.[228] The representatives of the noblemen and the Székelys wrote a joint memorandum to perusade him to withdraw his reforms in 1787, but he revoked most of his decrees only on his deathbed in 1790.[229] At the Diet that Joseph's successor, Leopold II, convoked in December 1790, the Székely György Aranka proposed the establishment of the Transylvanian Hungarian Philological Society.[230][231] On the other hand, the Székely delegates did not support the proposed union of Transylvania with Hungary, because they feared that it would jeopardize their traditional liberties.[232]

Transylvanian culture flourished in the early 19th century.[233] Farkas Bolyai improved the teaching of natural sciences at the college of Marosvásárhely.[234] Sándor Kőrösi Csoma, who left Székely Land for Central Asia to search for the Hungarians' ancient homeland, compiled the first Tibetan-English dictionary.[230][235] Sándor Farkas Bölöni published a book about his journeys in England and the United States, describing the latter as the country of "common sense".[230][236] Székely noblemen[note 14] and scholars[note 15] who adopted the ideas of Liberalism demanded the unification of Hungary and Transylvania.[237] However, Conservative noblemen[note 16] headed the seats.[237]

Revolution

A group of young artists and scholars published the reform program of the radical delegates of the Diet of Hungary without official authorization in Buda (the capital of Hungary) on 15 March 1848.[238] Six days later the radical burghers and students of Kolozsvár accepted a similar program, in which they also demanded a remedy to the grievances of the Székely people.[239] Before long, the assemblies of the Székely seats replaced the Conservative royal judges with Liberal politicians.[239]

The Diet of Transylvania, which was dominated by ethnic Hungarian delegates, voted for the union of Transylvania and Hungary on 30 May.[240] The Diet also abolished serfdom on 6 June.[241] The new law secured a plot of land even for the cotters, with the exception of those who had settled in a "Székey inheritance", because the division of the properties of free Székelys would have created thousands of smallholders living below the level of subsistence.[242] The population of Székely Land had doubled between 1767 and 1846,[note 17] but the territory of arable lands could not be increased.[243] Zsigmond Perényi (whom the Diet of Hungary appointed to study the problem) proposed that the landless Székely peasants should be settled in Banat.[244]

Lajos Batthyány, Prime Minister of Hungary, urged the Székelys to take up arms for the revolutionary government.[245] Before long, three Székely battalions joined the Hungarian army and fought against Josip Jelačić, Ban of Croatia, who had turned against the Hungarian government.[245] The government dissolved the Military Frontier to abolish the authority of the imperial officials over the Székely regiments.[246] Most Romanians and Saxons, who opposed the union of Transylvania and Hungary, sided with the royal court, which caused a civil war.[240][247] Before long, hundreds of Hungarians were massacred in the counties.[248]

Batthyány's commissioner, László Berzenczey convoked the general assembly of the Székelys to Agyagfalva, threatening those who would not attend with capital punishment in accordance with customary law.[246] On 18 October, the assembly declared that all Székelys were equal before the law.[249] An army of 30,000 strong was set up.[249] The Székely troops pillaged the Saxon town of Szászrégen (now Reghin in Romania), but the cannons of the imperial army forced them to flee from the battlefield at Marosvásárhely.[250] Before long, imperial troops occupied Marosszék and Udvarhelyszék, but the Székelys of Háromszék resisted till the end of 1848, preventing General Anton Puchner from assisting the imperial army in Hungary.[251] The dozens of cannons that Áron Gábor (a former artillery officer) produced during the fights contributed to the success of the resistance.[252]

By the end of 1848 – beginning of 1849, Székelys joined the army set up by General Józef Bem and took part in his successful campaigns driving out Habsburg troops from Transylvania. The successful campaign was finally crushed when the imperial Russian army intervened in Transylvania following a request from the Habsburg Monarchy.

Union with Hungary

.png)

In 1867, an agreement (Compromise) was made between Austria and Hungary about the creation of the Dual Monarchy. According to the Compromise, Transylvania was united with the Kingdom of Hungary. A decade later, a new county system was introduced in the Kingdom, which put an end to the long tradition of Székely Seats.

See also

- Treaty of Trianon

- Hungarian minority in Romania

- Magyar Autonomous Region

- Avar Khaganate

Notes

- Halom, Örlőcz, Jenő, Meggyes, Adorján and Ábrán.

- Adorján and Ábrán.

- Balázs, Gyerő, György, Karácson and Péter.

- Including, Kászon ("sour"), Kálnok ("muddy"), and Bölön ("henbane").

- For instance, Székelyderzs and Tarcsafalva.

- The Mikó, Mikes, Nemes and Kálnoky families.

- Deaneries of Telegd, Gyulafehérvár, Kézd and Torda.

- Aranyosszék, Csíkszék, Kézdiszék, Marosszék, Orbaiszék, Sepsiszék and Udvarhelyszék.

- For instance, Udvarfalva and Meggyesfalva (now Curteni and Mureșeni, respectively in Romania).

- For instance, Erdőszentgyörgy (now Sângeorgiu de Pădure in Romania) bears the name of one "Erdew" from the Meggyes lineage of the Meggyes kindred, who lived in the mid-14th century.

- Including, János Béldi, Miklós Mikó, Farkas and Imre Lázár.

- For instance, the Lázárs renovated their castle at Szárhegy (now Lăzarea in Romania), and the Dániels built a new castle at Vargyas (now Vârghiș in Romania).

- For instance, the Apors and Kálnokys.

- For instance, Baron Zsigmond Szentkereszti, László Berzenczey and Mihály Mikó.

- Including, Mózes Berde and Dániel Fábián.

- Baron Lázár Apor, Lajos Matskási and Ferenc Tholdalagi.

- The 1767 census recorded 37,145 families, suggesting that more than 185,000 people lived in Székely Land. According to the 1846 census, 379,500 people lived in the seats.

References

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 178.

- Egyed 2013, p. 9.

- Kristó 1996, p. 23.

- Hermann 2004, p. 1.

- Egyed 2013, pp. 10–11.

- Egyed 2013, p. 11.

- Kristó 1996, pp. 10–11.

- Kristó 1996, pp. 33–34, 137.

- Kristó 1996, p. 12.

- Engel 2001, p. 116.

- Egyed 2013, p. 13.

- Egyed 2013, p. 12.

- Sedlar 1994, p. 406.

- Egyed 2013, pp. 12–13.

- Kristó 1996, p. 66.

- Kristó 2003a, p. 130.

- Pop & Bolovan 2006, p. 161.

- Kristó 2003a, p. 128.

- Kordé 2001, p. 35.

- Kristó 2003b, pp. 96–97.

- The Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle (ch. 153), p. 134.

- Kristó 1996, p. 37.

- Kristó 2003b, p. 97.

- Egyed 2013, p. 51.

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 179.

- Engel 2001, p. 117.

- Kordé 2001, p. 64.

- Pop & Bolovan 2006, pp. 161–162.

- Simon of Kéza: The Deeds of the Hungarians (ch. 21.), p. 71.

- Kristó 2003a, p. 131.

- Curta 2006, pp. 352–353.

- Egyed 2013, p. 15.

- Sălăgean 2016, p. 17.

- Curta 2006, p. 385.

- Kristó 2003a, p. 132.

- Curta 2006, p. 405.

- Kristó 2003a, pp. 38, 132.

- Egyed 2013, p. 14.

- Kristó 2003a, pp. 58–59, 134–135.

- Kristó 2003a, p. 133.

- Kristó 2003b, pp. 141–142.

- Egyed 2013, p. 22.

- Egyed 2013, p. 24.

- Egyed 2013, pp. 16–17.

- Egyed 2013, p. 17.

- Kristó 2003b, pp. 178–179.

- Sălăgean 2016, p. 135.

- Sălăgean 2016, p. 137.

- Sălăgean 2016, p. 136.

- Kristó 2003, p. 133.

- Egyed 2013, p. 46.

- Kristó 2003a, p. 136.

- Kristó 2003a, p. 137.

- Egyed 2013, pp. 18, 46.

- Egyed 2013, pp. 18, 51.

- Egyed 2013, pp. 41, 46.

- Egyed 2013, p. 50.

- Egyed 2013, pp. 46–47.

- Egyed 2013, p. 47.

- Sălăgean 2016, p. 154.

- Sălăgean 2016, p. 182.

- Sălăgean 2016, p. 156.

- Kontler 1999, p. 84.

- Sălăgean 2016, p. 195.

- Kristó 2003a, p. 231.

- Egyed 2013, p. 18.

- Kristó 2003a, p. 135.

- Egyed 2013, p. 19.

- Egyed 2013, p. 21.

- Egyed 2013, pp. 30–32.

- Egyed 2013, p. 40.

- Benkő & Székely 2008, p. 13.

- Egyed 2013, p. 48.

- Benkő & Székely 2008, p. 17.

- Benkő & Székely 2008, pp. 12, 18.

- Sedlar 1994, p. 93.

- Engel 2001, p. 166.

- Egyed 2013, p. 58.

- Egyed 2013, p. 75.

- Egyed 2013, p. 43.

- Egyed 2013, pp. 50–51.

- Benkő & Székely 2008, p. 12.

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 236.

- Barta et al. 1994, pp. 236–237.

- Benkő & Székely 2008, p. 14.

- Benkő & Székely 2008, p. 18, 24.

- Barta et al. 1994, pp. 209, 236.

- Pop & Bolovan 2006, p. 258.

- Barta et al. 1994, pp. 226.

- Engel 2001, p. 277.

- Kontler 1999, p. 110.

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 224.

- Pop & Bolovan 2006, p. 259.

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 240.

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 242.

- Barta et al. 1994, pp. 240–241.

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 241.

- Egyed 2013, p. 141.

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 227.

- Egyed 2013, p. 61.

- Engel 2001, p. 298.

- Egyed 2013, p. 62.

- Engel 2001, p. 115.

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 237.

- Egyed 2013, p. 66.

- Egyed 2013, pp. 66–67.

- Egyed 2013, p. 67.

- Egyed 2013, p. 68.

- Egyed 2013, p. 70.

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 238.

- Egyed 2013, p. 72.

- Engel 2001, pp. 363–364.

- Engel 2001, p. 370.

- Pop & Bolovan 2006, p. 280.

- Kontler 1999, p. 139.

- Egyed 2013, pp. 83–84.

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 249.

- Kontler 1999, p. 140.

- Kontler 1999, p. 142.

- Pop & Bolovan 2006, p. 281.

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 253.

- Egyed 2013, pp. 96–97.

- Egyed 2013, p. 97.

- Keul 2009, p. 102.

- Egyed 2013, p. 143.

- Kontler 1999, pp. 146–147.

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 257.

- Egyed 2013, p. 85.

- Kontler 1999, p. 148.

- Egyed 2013, p. 137.

- Egyed 2013, p. 88.

- Egyed 2013, p. 89.

- Egyed 2013, p. 91.

- Barta et al. 1994, pp. 283–284.

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 284.

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 285.

- Egyed 2013, p. 94.

- Egyed 2013, p. 95.

- Egyed 2013, p. 98.

- Egyed 2013, p. 99.

- Keul 2009, p. 97.

- Keul 2009, p. 111.

- Egyed 2013, pp. 99–100.

- Keul 2009, p. 130.

- Egyed 2013, p. 102.

- Egyed 2013, p. 103.

- Keul 2009, p. 121.

- Keul 2009, p. 129.

- Keul 2009, pp. 130–131.

- Keul 2009, p. 140.

- Pop & Bolovan 2006, p. 306.

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 295.

- Egyed 2013, p. 105.

- Egyed 2013, pp. 105–106.

- Pop & Bolovan 2006, p. 310.

- Barta et al. 1994, pp. 295–296.

- Horn 2002, p. 202.

- Pop & Bolovan 2006, p. 311.

- Keul 2009, pp. 142–143.

- Keul 2009, p. 142.

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 296.

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 297.

- Egyed 2013, p. 111.

- Egyed 2013, p. 112.

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 335.

- Egyed 2013, p. 121.

- Egyed 2013, pp. 148–149.

- Egyed 2013, p. 136.

- Egyed 2013, p. 122.

- Egyed 2013, p. 153.

- Egyed 2013, p. 154.

- Egyed 2013, p. 125.

- Egyed 2013, p. 133.

- Egyed 2013, pp. 133–134.

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 386.

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 407.

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 336.

- Egyed 2013, p. 127.

- Egyed 2013, p. 126.

- Keul 2009, pp. 198–199.

- Keul 2009, p. 200.

- Pop & Bolovan 2006, p. 338.

- Egyed 2013, p. 155.

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 359.

- Barta et al. 1994, pp. 360,397–398.

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 369.

- Pop & Bolovan 2006, p. 354.

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 371.

- Pop & Bolovan 2006, pp. 354–355.

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 372.

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 374.

- Pop & Bolovan 2006, p. 356.

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 377.

- Kontler 1999, pp. 185–186.

- Egyed 2013, p. 158.

- Kontler 1999, p. 187.

- Egyed 2013, pp. 159–160.

- Egyed 2013, p. 160.

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 381.

- Kontler 1999, p. 189.

- Pop & Bolovan 2006, p. 359.

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 411.

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 415.

- Pop & Bolovan 2006, p. 413.

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 430.

- Pop & Bolovan 2006, p. 414.

- Egyed 2013, p. 164.

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 431.

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 417.

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 418.

- Egyed 2013, p. 166.

- Egyed 2013, p. 167.

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 433.

- Egyed 2013, p. 169.

- Egyed 2013, p. 170.

- Egyed 2013, p. 176.

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 755.

- Egyed 2013, p. 178.

- Egyed 2013, p. 172.

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 434.

- Egyed 2013, p. 177.

- Egyed 2013, p. 182.

- Egyed 2013, p. 181.

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 435.

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 436.

- Kontler 1999, p. 212.

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 446.

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 447.

- Barta et al. 1994, pp. 447–448.

- Egyed 2013, pp. 190–191.

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 449.

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 450.

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 454.

- Egyed 2013, p. 190.

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 456.

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 462.

- Egyed 2013, p. 193.

- Kontler 1999, pp. 247–248.

- Egyed 2013, p. 195.

- Hitchins 2014, p. 99.

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 496.

- Egyed 2013, p. 199.

- Egyed 2013, pp. 184, 203.

- Egyed 2013, p. 203.

- Egyed 2013, p. 200.

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 508.

- Barta et al. 1994, pp. 501, 506–508.

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 510.

- Egyed 2013, p. 208.

- Barta et al. 1994, p. 512.

- Egyed 2013, pp. 209–211.

- Egyed 2013, p. 210-211.

Sources

Primary sources

- Anonymus, Notary of King Béla: The Deeds of the Hungarians (Edited, Translated and Annotated by Martyn Rady and László Veszprémy) (2010). In: Rady, Martyn; Veszprémy, László; Bak, János M. (2010); Anonymus and Master Roger; CEU Press; ISBN 978-9639776951.

- Simon of Kéza: The Deeds of the Hungarians (Edited and translated by László Veszprémy and Frank Schaer with a study by Jenő Szűcs) (1999). CEU Press. ISBN 963-9116-31-9.

- Stephen Werbőczy: The Customary Law of the Renowned Kingdom of Hungary in Three Parts (1517) (Edited and translated by János M. Bak, Péter Banyó and Martyn Rady with an introductory study by László Péter) (2005). Charles Schlacks, Jr. Publishers. ISBN 1-884445-40-3.

- The Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle: Chronica de Gestis Hungarorum (Edited by Dezső Dercsényi) (1970). Corvina, Taplinger Publishing. ISBN 0-8008-4015-1.

Secondary sources

- Barta, Gábor; Bóna, István; Köpeczi, Béla; Makkai, László; Miskolczy, Ambrus; Mócsy, András; Péter, Katalin; Szász, Zoltán; Tóth, Endre; Trócsányi, Zsolt; R. Várkonyi, Ágnes; Vékony, Gábor (1994). History of Transylvania. Akadémiai Kiadó. ISBN 963-05-6703-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Benkő, Elek; Székely, Attila (2008). Középkori udvarház és nemesség a Székelyföldön [Medieval Manor and Nobility in Székely Land] (in Hungarian). Nap Kiadó. ISBN 978-963-9658-28-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Curta, Florin (2006). Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500-1250. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-89452-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Egyed, Ákos (2013). A székelyek rövid története a megtelepedéstől 1989-ig (in Hungarian). Pallas-Akadémiai Könyvkiadó. ISBN 978-973-665-365-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Engel, Pál (2001). The Realm of St Stephen: A History of Medieval Hungary, 895–1526. I.B. Tauris Publishers. ISBN 1-86064-061-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hermann, Gusztáv Mihály (2004). Székely történeti kistükör [Small Mirror of Székely History] (in Hungarian). Litera. ISBN 973-85950-6-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hitchins, Keith (2014). A Concise History of Romania. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-69413-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Horn, Ildikó (2002). Báthory András [Andrew Báthory] (in Hungarian). Új Mandátum. ISBN 963-9336-51-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Keul, István (2009). Early Modern Religious Communities in East-Central Europe: Ethnic Diversity, Denominational Plurality, and Corporative Politics in the Principality of Transylvania (1526–1691). Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-17652-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kontler, László (1999). Millennium in Central Europe: A History of Hungary. Atlantisz Publishing House. ISBN 963-9165-37-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kordé, Zoltán (2001). A középkori székelység: krónikák és oklevelek a középkori székelyekről [Székely in the Middle Ages: Chronicles and Charters of the Medieval Székely People] (in Hungarian). Pro-Print Könyvkiadó. ISBN 973-9311-77-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kristó, Gyula (1996). A székelyek eredetéről [On the Origin of the Székely] (in Hungarian). Szegedi Középkorász Műhely. ISBN 963-482-150-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kristó, Gyula (2003a). Early Transylvania (895-1324). Lucidus Kiadó. ISBN 963-9465-12-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kristó, Gyula (2003b). Háborúk és hadviselés az Árpád-korban [Wars and Warfare under the Árpáds] (in Hungarian). Szukits Könyvkiadó. ISBN 963-9441-87-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Madgearu, Alexandru (2005). The Romanians in the Anonymous Gesta Hungarorum: Truth and Fiction. Romanian Cultural Institute, Center for Transylvanian Studies. ISBN 973-7784-01-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pop, Ioan-Aurel; Bolovan, Ioan (2006). History of Romania: Compendium. Romanian Cultural Institute (Center for Transylvanian Studies). ISBN 978-973-7784-12-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sedlar, Jean W. (1994). East Central Europe in the Middle Ages, 1000–1500. University of Washington Press. ISBN 0-295-97290-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sălăgean, Tudor (2016). Transylvania in the Second Half of the Thirteenth Century: The Rise of the Congregational System. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-24362-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Balogh, Judit (2005). A székely nemesség kialakulásának folyamata a 17. század első felében [Development of the Székely Nobility in the First Half of the Seventeenth Century] (in Hungarian). Erdélyi Múzeum-Egyesület. ISBN 973-8231-48-5.

- Ehrenthal, Ferenc Frank (2014). From Mongolia to Transylvania: Székely Origins and Radical Faith: The Birth of Unitarianism. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1494926953.

External links

- Köpeczi, Béla; Makkai, László; Mócsy, András; Szász, Zoltán; Barta, Gábor (2001–2002), History of Transylvania, Atlantic Research and Publications, Inc., retrieved 23 August 2016