Alexander Lukashenko

Alexander Grigoryevich Lukashenko or Alyaksandr Ryhoravich Lukashenka (Belarusian: Алякса́ндр Рыго́равіч Лукашэ́нка, IPA: [alʲaˈksand(a)r rɨˈɣɔravʲitʂ lukaˈʂɛnka], Russian: Алекса́ндр Григо́рьевич Лукаше́нко, IPA: [ɐlʲɪˈksandr ɡrʲɪˈɡorʲjɪvʲɪtɕ ɫʊkɐˈʂɛnkə]; born 30 August 1954) is a Belarusian politician, who has served as president of Belarus since the establishment of the office 26 years ago, on 20 July 1994.[7] Before launching his political career, Lukashenko worked as director of a collective farm (kolkhoz), and served in the Soviet Border Troops and in the Soviet Army. He was the only deputy of the Supreme Council of Belarus to vote against the 1991 dissolution of the Soviet Union.

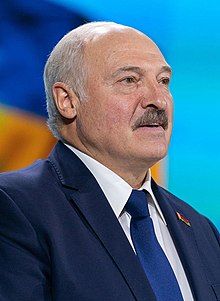

Alexander Lukashenko Аляксандр Лукашэнка Александр Лукашенко | |

|---|---|

Lukashenko in 2019 | |

| President of Belarus | |

| Assumed office 20 July 1994 Disputed with Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya since 9 August 2020[1][2][3][4] | |

| Prime Minister | |

| Preceded by | Office established Myechyslaw Hryb (Chairman of the Supreme Soviet) |

| Chairman of the Supreme State Council of the Union State | |

| Assumed office 26 January 2000 | |

| Chairman of the Council of Ministers | |

| General Secretary | |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Member of the Belarusian Supreme Council | |

| In office 1990–1994 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Aleksandr Grigoryevich Lukashenko 30 August 1954 Kopys, Belarusian SSR, Soviet Union (now Belarus) |

| Political party | Independent (1992–present) |

| Other political affiliations |

|

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | |

| Salary | $31,000 annual[5] |

| Signature | |

| Website | president |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service |

|

| Rank | Supreme Commander (Podpolkovnik)[6] |

Lukashenko opposed Western-backed economic shock therapy during the post-Soviet transition, which during the 1990s generally spared Belarus from recessions as devastating as those in other post-Soviet states like Russia.

He has supported state ownership of key industries in Belarus. Lukashenko's government has also retained much of the country's Soviet-era symbolism, especially those that are related to victory in World War II.[8]

Lukashenko heads an authoritarian regime in Belarus.[9][10] Elections are not free and fair, opponents of the regime are repressed, and the media is not free.[11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18] Since 2006, the European Union and the United States have periodically imposed sanctions on Lukashenko and on other Belarusian officials for human rights violations and challenging US national interests.[19][20]

Early life and career (1954–94)

Lukashenko was born on 30 August 1954[21][22] in the settlement of Kopys in the Vitebsk Oblast of the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic. His maternal grandfather, Trokhym Ivanovich Lukashenko, had been born in the Sumy Oblast of Ukraine near Shostka (today village of Sobycheve).[23] Lukashenko grew up without a father in his childhood, leading him to be taunted by his schoolmates for having an unmarried mother.[24] Due to this, the origin of his patronymic Grigorevich is unknown. His mother, Ekaterina Trofimovna Lukashenko (1924–2015), worked as a milkmaid.[25]

Lukashenko went to Alexandria secondary school. He graduated from the Mogilev Pedagogical Institute (now Mogilev State A. Kuleshov University) in 1975, after 4 years studying there and the Belarusian Agricultural Academy in Horki in 1985.

Military career

He served in the Border Guard (frontier troops) from 1975 to 1977, where he was an instructor of the political department of military unit No. 2187 of the Western Frontier District in Brest and in the Soviet Army from 1980 to 1982. In addition, he led an All-Union Leninist Young Communist League (Komsomol) chapter in Mogilev from 1977 to 1978. While in the Soviet Army, Lukashenko was a deputy political officer of the 120th Guards Motor Rifle Division, which was based in Minsk.[26] He later rejoined as a tank specialist.

Post-military career and entry into politics

In 1979, he joined the ranks of the CPSU. After leaving the military, he became the deputy chairman of a collective farm in 1982 and in 1985, he was promoted to the post of director of the Gorodets state farm and construction materials plant in the Shkloŭ district.[27] In 1987, he was appointed as the director of the Gorodets state farm in Shkloŭ district and in early 1988, was one of the first in Mogilev Region to introduce a leasing contract to a state farm.[28]

In 1990, Lukashenko was elected Deputy to the Supreme Council of the Republic of Belarus. Having acquired a reputation as an eloquent opponent of corruption, Lukashenko was elected in April 1993 to serve as the interim chairman of the anti-corruption committee of the Belarusian parliament.[29] In late 1993 he accused 70 senior government officials, including the Supreme Soviet chairman Stanislav Shushkevich and prime minister Vyacheslav Kebich, of corruption including stealing state funds for personal purposes. While the charges ultimately proved to be without merit, Shushkevich resigned his chairmanship due to the embarrassment of this series of events and losing a vote of no-confidence.[30][31] He served in that position until July 1994.

President of Belarus

First term (1994–2001)

A new Belarusian constitution enacted in early 1994 paved the way for the first democratic presidential election on 23 June and 10 July. Six candidates stood in the first round, including Lukashenko, who campaigned as an independent on a populist platform. Shushkevich and Kebich also ran, with the latter regarded as the clear favorite.[32] Lukashenko won 45.1% of the vote while Kebich received 17.4%, Zyanon Paznyak received 12.9% and Shushkevich, along with two other candidates, received less than 10% of votes.[32] Lukashenko won the second round of the election on 10 July with 80.1% of the vote.[32][33] Shortly after his election, he addressed the State Duma of the Russian Federation in Moscow proposing a new Union of Slavic states, which would culminate in the creation of the Union of Russia and Belarus in 1999.[34]

In May 1995, Belarus held a referendum on changing its national symbols; the referendum also made the Russian language equal to Belarusian, and forged closer economic ties to Russia. Lukashenko was also given the ability to disband the Supreme Soviet by decree.[35] In the summer of 1996, deputies of the 199-member Belarusian parliament signed a petition to impeach Lukashenko on charges of violating the Constitution.[36] Shortly after that, a referendum was held on 24 November 1996 in which four questions were offered by Lukashenko and three offered by a group of Parliament members. The questions ranged from social issues (changing the independence day to 3 July (the date of the liberation of Minsk from Nazi forces in 1944), abolition of the death penalty) to the national constitution. As a result of the referendum, the constitution that was amended by Lukashenko was accepted and the one amended by the Supreme Soviet was voided. On 25 November, it was announced that 70.5% of voters, of an 84% turnout, had approved the amended constitution. The US and the EU, however, refused to accept the legitimacy of the referendum.[37][38]

After the referendum, Lukashenko convened a new parliamentary assembly from those members of the parliament who were loyal to him.[39] After between ten and twelve deputies withdrew their signature from the impeachment petition, only about forty deputies of the old parliament were left and the Supreme Soviet was dismissed by Lukashenko.[40] Nevertheless, international organizations and many Western countries do not recognize the current parliament given the way it was formed.[41][42] At the start of 1998, the Central Bank of Russia suspended trading in the Belarusian ruble, which led to a collapse in the value of the currency. Lukashenko responded by taking control of the National Bank of the Republic of Belarus, sacking the entire bank leadership and blaming the West for the free fall of the currency.[43]

Lukashenko blamed foreign governments for conspiring against him and, in April 1998, expelled ambassadors from the Drazdy complex near Minsk and moved them to another building. The Drazdy conflict caused an international outcry and resulted in a travel ban on Lukashenko from the EU and the US.[44] Although the ambassadors eventually returned after the controversy died down, Lukashenko stepped up his rhetorical attacks against the West. He stated that Western governments were trying to undermine Belarus at all levels, even sports, during the 1998 Winter Olympics in Nagano, Japan.[45]

Upon the outbreak of the Kosovo War in 1999, Lukashenko suggested to Yugoslav President Slobodan Milošević that Yugoslavia join the Union of Russia and Belarus.[46]

Second term (2001–2006)

Under the original constitution, Lukashenko should have been up for reelection in 1999. However, the 1996 referendum extended Lukashenko's term for two additional years. In the 9 September 2001 election, Lukashenko faced Vladimir Goncharik and Sergei Gaidukevich.[47] During the campaign, Lukashenko promised to raise the standards of farming, social benefits and increase industrial output of Belarus.[48] Lukashenko won in the first round with 75.65% of the vote. The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) said the process "failed to meet international standards".[48] Jane's Intelligence Digest surmised that the price of Russian support for Lukashenko ahead of the 2001 presidential election was the surrender of Minsk's control over its section of the Yamal–Europe gas pipeline.[49] After the results were announced declaring Lukashenko the winner, Russia publicly welcomed Lukashenko's re-election; the Russian President, Vladimir Putin, telephoned Lukashenko and offered a message of congratulations and support.[48]

Following the 2003 invasion of Iraq, American intelligence agencies reported that aides of Saddam Hussein managed to acquire Belarusian passports while in Syria, but that it was unlikely that Belarus would offer a safe haven for Saddam and his two sons.[50] This action, along with arms deals with Iraq and Iran, prompted Western governments to take a tougher stance against Lukashenko. The US was particularly angered by the arms sales, and American political leaders increasingly began to refer to Belarus as "Europe's last dictatorship".[51] The EU was concerned for the security of its gas supplies from Russia, which are piped through Belarus, and took an active interest in Belarusian affairs. With the accession of Poland, Latvia and Lithuania, the EU's border with Belarus has grown to more than 1000 kilometers.[52]

During a televised address to the nation on 7 September 2004, Lukashenko announced plans for a referendum to eliminate presidential term limits. This was held on 17 October 2004, the same day as parliamentary elections, and, according to official results, was approved by 79.42% of voters. Previously, Lukashenko had been limited to two terms and thus would have been constitutionally required to step down after the presidential elections in 2006.[24][53] Opposition groups, the OSCE, the European Union, and the US State Department stated that the vote fell short of international standards. An example of the failure, cited by the OSCE, was the pre-marking of ballots. Belarus grew economically under Lukashenko, but much of this growth was due to Russian crude oil which was imported at below-market prices, refined, and sold to other European countries at a profit.[24]

Third term (2006–2010)

After Lukashenko confirmed he was running for re-election in 2005, opposition groups began to seek a single candidate. On 16 October 2005, on the Day of Solidarity with Belarus, the political groups Zubr and Third Way Belarus encouraged all opposition parties to rally behind one candidate to oppose Lukashenko in the 2006 election. Their chosen candidate was Alexander Milinkevich.[54] Lukashenko reacted by saying that anyone going to opposition protests would have their necks wrung "as one might a duck".[24] On 19 March 2006, exit polls showed Lukashenko winning a third term in a landslide, amid opposition reports of vote-rigging and fear of violence. The Belarusian Republican Youth Union gave Lukashenko 84.2% and Milinkevich 3.1%. The Gallup Organisation noted that the Belarusian Republican Youth Union are government-controlled and released the exit poll results before noon on election day even though voting stations did not close until 8 pm.[55]

Belarusian authorities vowed to prevent any large-scale demonstrations following the election (such as those that marked the Orange Revolution in Ukraine). Despite their efforts, the opposition had the largest number of demonstrators in years, with nightly protests in Minsk continuing for a number of days after the election. The largest protest occurred on election night; reporters for the Associated Press estimated that approximately 10,000 people turned out.[56] Election observers from the Russia-led Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) differed on the Belarusian election.[57]

The OSCE declared on 20 March 2006 that the "presidential election failed to meet OSCE commitments for democratic elections." Lukashenko "permitted State authority to be used in a manner which did not allow citizens to freely and fairly express their will at the ballot box... a pattern of intimidation and the suppression of independent voices... was evident throughout the campaign."[58] The heads of all 25 EU countries declared that the election was "fundamentally flawed".[59] In contrast, the Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs declared, "Long before the elections, the OSCE's Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights had declared that they [the elections] would be illegitimate and it was pretty biased in its commentaries on their progress and results, thus playing an instigating role."[59] Lukashenko later stated that he had rigged the election results, but against himself, in order to obtain a majority more typical of European countries. Although he had won 93.5% of the vote, he said, he had directed the government to announce a result of 86%.[60][61]

Some Russian nationalists, such as Dmitry Rogozin and the Movement Against Illegal Immigration, stated that they would like to see Lukashenko become President of Russia in 2008. Lukashenko responded that he would not run for the Russian presidency, but that if his health was still good, he might run for reelection in 2011.[62]

In September 2008, parliamentary elections were held. Lukashenko had allowed some opposition candidates to stand, though in the official results, opposition members failed to get a seat out of the available 110. OSCE observers described the vote as "flawed", including "several cases of deliberate falsification of results".[63] Opposition members and supporters demonstrated in protest.[63] According to the Nizhny Novgorod-based CIS election observation mission, the findings of which are often dismissed by the West,[64] the elections in Belarus conformed to international standards.[65] Lukashenko later commented that the opposition in Belarus was financed by foreign countries and was not needed.[66]

In April 2009, he held talks with Pope Benedict XVI in the Vatican, Lukashenko's first visit to Western Europe after a travel ban on him a decade earlier.[67]

Fourth term (2010–2015)

Lukashenko was one of ten candidates registered for the presidential election held in Belarus on 19 December 2010. Though originally envisaged for 2011, an earlier date was approved "to ensure the maximum participation of citizens in the electoral campaign and to set most convenient time for the voters".[68] The run-up to the campaign was marked by a series of Russian media attacks on Lukashenko.[69] The Central Election Committee said that all nine opposition figures were likely to get less than half the vote total that Lukashenko would get.[70] Though opposition figures alleged intimidation[71] and that "dirty tricks" were being played, the election was seen as comparatively open as a result of desire to improve relations with both Europe and the US.[70]

On election day, two presidential candidates were seriously beaten by police[72] in different opposition rallies.[73][74][75] On the night of the election, opposition protesters chanting "Out!", "Long live Belarus!" and other similar slogans attempted to storm the building of the government of Belarus, smashing windows and doors before riot police were able to push them back.[76] The number of protesters was reported by major news media as being around or above 10,000 people.[77][78][79][80] At least seven of the opposition presidential candidates were arrested.[72]

Several of the opposition candidates, along with their supporters and members of the media, were arrested. Many were sent to prison, often on charges of organizing a mass disturbance. Examples include Andrei Sannikov,[81] Alexander Otroschenkov,[82] Ales Michalevic,[83] Mikola Statkevich,[84] and Uladzimir Nyaklyayew.[85] Sannikov's wife, journalist Irina Khalip, was put under house arrest.[86] Yaraslau Ramanchuk's party leader, Anatoly Lebedko, was also arrested.[87]

The CEC said that Lukashenko won 79.65% of the vote (he gained 5,130,557 votes) with 90.65% of the electorate voting.[88] The OSCE categorized the elections as "flawed" while the CIS mission observers praised them as "free and transparent".[89] However, the OSCE also stated that some improvements were made in the run-up to the election, including the candidates' use of television debates and ability to deliver their messages unhindered.[90] Several European foreign ministers issued a joint statement calling the election and its aftermath an "unfortunate step backwards in the development of democratic governance and respect for human rights in Belarus."[91]

Lukashenko's inauguration ceremony of 22 January 2011 was boycotted by EU ambassadors, and only thirty-two foreign diplomats attended.[92][93] During this ceremony, Lukashenko defended the legitimacy of his re-election and vowed that Belarus would never have its own version of the 2004 Orange Revolution in Ukraine or Georgia's 2003 Rose Revolution.[92]

Effective 31 January 2011, the EU renewed a travel ban, prohibiting Lukashenko and 156 of his associates from traveling to EU member countries, as a result of the crackdown on opposition supporters.[94][95][96]

Lukashenko was supportive of China's Belt and Road Initiative global infrastructure development strategy, and the inception in 2012 of the associated low-tax China–Belarus Industrial Park near Minsk National Airport planned to grow to 112 square kilometres (43 sq mi) by the 2060s.[97][98]

Fifth term (2015–2020)

_03.jpg)

.jpg)

On 11 October 2015, Lukashenko was elected for his fifth term as the President of Belarus. Just over three weeks later, he was inaugurated in the Independence Palace in the presence of attendees such as former President of Ukraine Leonid Kuchma, Chairman of the Russian Communist Party Gennady Zyuganov and Belarusian biathlete Darya Domracheva.[99] On mid-September 2017, Lukashenko oversaw the advancement of joint Russian and Belarusian military relations during the military drills that were part of the Zapad 2017 exercise.[100][101]

In August 2018, Lukashenko fired his prime minister Andrei Kobyakov and various other officials due to a corruption scandal.[102] Sergei Rumas was appointed to take his place as prime minister.[102] In May 2017, Lukashenko signed a decree on the Foundation of the Directorate of the 2019 European Games in Minsk.[103] In April 2019, Lukashenko announced that the games were on budget and on time and eventually he opened the 2nd edition of the event on 21 June.[104][105] Between 1–3 July 2019, he oversaw the country's celebrations of the 75th anniversary of the Minsk Offensive, which culminated in an evening military parade of the Armed Forces of Belarus on the last day, which is the country's Independence Day.[106]

In August 2019, Lukashenko met with former Kyrgyz President Kurmanbek Bakiyev, who has lived in exile in Minsk since 2010, in the Palace of Independence to mark Bakiyev's 70th birthday, which he had marked several days earlier.[107] The meeting, which included the presentation of traditional flowers and symbolic gifts, angered the Kyrgyz Foreign Ministry which stated that the meeting "fundamentally does not meet the principles of friendship and cooperation between the two countries".[108][109][110][111] On 29 August, John Bolton, the National Security Advisor of the United States, was received by Lukashenko during his visit to Minsk, which was the first of its kind in 18 years.[112][113][114] In November 2019, Lukashenko visited the Austrian capital of Vienna on a state visit, which was his first in three years to an EU country. During the visit, he met with President Alexander Van der Bellen, Chancellor Brigitte Bierlein, and National Council President Wolfgang Sobotka. He also paid his respects at the Soviet War Memorial at the Schwarzenbergplatz.[115][116][117]

During the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, he undertook two working visits to Russia, one of the few European leaders to undertake foreign visits during the pandemic. He also received Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban during his state visit to Minsk.[118] Orban called for an end to EU sanctions on Belarus during this visit.[119] His first visit to Russia was to attend the rescheduled Moscow Victory Day Parade on Red Square together with his son.[120]

Sixth term (2020–present)

On 9 August 2020, according to the preliminary count, Lukashenko was elected for his sixth term as the President of Belarus.[121] US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo has warned that the election was "not free and fair".[122]

Mass protests erupted across Belarus following the 2020 Belarusian presidential election which was marred by allegations of widespread electoral fraud.[123][124] Subsequently, opposition presidential candidate Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya claimed she had won the presidential election with between 60 and 70% of the vote[125][126] and formed a Coordination council to facilitate the peaceful and orderly transfer of power in Belarus.[127][128]

On 15 August 2020, Lithuanian Foreign Minister Linas Linkevicius referred to Lukashenko as the "former president" of Belarus.[129]

On 15 August, it was reported that President Lukashenko's authorities asked Kremlin representatives about the possibility of Lukashenko escaping to Russia. Furthermore, it was reported that Russia admits that Lukashenko's resignation from the post of head of state is likely.[130][131]

On 17 August the members of the European Parliament issued a joint statement which stated that they do not recognise Alexander Lukashenko as the president of Belarus, considering him to be persona non grata in the European Union.[132]

Policy

Domestic policy

Lukashenko promotes himself as a "man of the people." Due to his style of rule, he is often informally referred to as бацька (bats'ka, "dad").[51] He was elected chairman of the Belarusian Olympic Committee in 1997.[133] Lukashenko wanted to rebuild Belarus when he took office;[134] the economy was in freefall, due to declining industry and lack of demand for Belarusian goods.[135] Lukashenko kept many industries under the control of the government.[136] In 2001, he stated his intention to improve the social welfare of his citizens and to make Belarus "powerful and prosperous."[137]

With the gaining to the power of Lukashenko in 1994, the Russification policy of Russian Imperial and Soviet era was renewed.[138][139][140][141]

Since the November 1996 referendum, Lukashenko has effectively held all governing power in the nation. If the House of Representatives rejects his choice for prime minister twice, he has the right to dissolve it. His decrees have greater weight than ordinary legislation. He also has near-absolute control over government spending; parliament can only increase or decrease spending with his permission.[40] However, the legislature is dominated by his supporters in any event, and there is no substantive opposition to presidential decisions. Indeed, every seat in the lower house has been held by supporters of the president for all but one term since 2004. He also appoints eight members of the upper house, the Council of the Republic, as well as nearly all judges.

Economic policies

Lukashenko's early economic policies aimed to prevent issues that occurred in other post-Soviet states, such as the establishment of oligarchic structures and mass unemployment.[142] The unemployment rate for the country at the end of 2011 was at 0.6% of the population (of 6.86 million eligible workers), a decrease from 1995, when unemployment was 2.9% with a working-eligible population of 5.24 million.[143] The per-capita gross national income rose from US$1,423 in 1993 to US$5,830 at the end of 2011.[144]

One major economic issue Lukashenko faced throughout his presidency was the value of the Belarusian ruble. For a time it was pegged to major foreign currencies, such as the euro, US dollar and the Russian ruble in order to maintain the stability of the Belarusian ruble.[145] Yet, the currency has experienced several periods of devaluation. A major devaluation took place in 2011 after the government announced that average salaries would increase to US$500.[146] The 2011 devaluation was the largest on record for the past twenty years according to the World Bank.[147]

Belarus also had to seek a bailout from international sources and, although it has received loans from China, loans from the IMF and other agencies depend on how Belarus reforms its economy.[148][149]

Some critics of Lukashenko, including the opposition group Zubr, use the term Lukashism to refer to the political and economic system Lukashenko has implemented in Belarus.[150] The term is also used more broadly to refer to an authoritarian ideology based on a cult of his personality and nostalgia for Soviet times among certain groups in Belarus.[151][152] The US Congress sought to aid the opposition groups by passing the Belarus Democracy Act of 2004 to introduce sanctions against Lukashenko's government and provide financial and other support to the opposition.[8] Lukashenko supporters argue that his rule spared Belarus the turmoil that beset many other former Soviet countries.[153][154] Lukashenko commented on the criticism of him by saying: "I've been hearing these accusations for over 10 years and we have got used to it. We are not going to answer them. I want to come from the premise that the elections in Belarus are held for ourselves. I am sure that it is the Belarusian people who are the masters in our state."[155]

Coronavirus

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Lukashenko stated that concerns about the pandemic were a "frenzy and a psychosis" and that working the tractors, drinking vodka and going to saunas could prevent people from infection from the virus. "People are working in tractors. No one is talking about the virus", Lukashenko said on 16 March 2020. "There, the tractor will heal everyone. The fields heal everyone". He also said: "I don’t drink, but recently I’ve been saying that people should not only wash their hands with vodka, but also poison the virus with it. You should drink the equivalent of 40–50 milliliters of rectified spirit daily", but he advised against doing so while at work.[156][157] By early May, Belarus was reported to have 15,000 diagnosed cases, one of the highest per capita rates of infection in Eastern Europe.[158]

On 28 July, Lukashenko announced he had asymptomatic COVID-19.[159] Neither the Presidential Administration nor the country's health service have commented on this inadvertent statement.[160]

Foreign policy

Lukashenko's relationship with the EU has been strained, in part by choice and in part by his policies towards domestic opponents. Lukashenko's repression of opponents caused him to be called "Europe's last dictator" and resulted in the EU imposing visa sanctions on him and a range of Belarusian officials. At times, the EU has lifted sanctions as a way to encourage dialogue or gain concessions from Lukashenko.[161] Since the EU adopted this policy of "change through engagement", it has supported economic and political reforms to help integrate the Belarusian state.[162]

Lukashenko's relationship with Russia, once his powerful ally and vocal supporter, has significantly deteriorated. The run-up to the 2010 Belarusian presidential election was marked by a series of Russian media attacks on Lukashenko.[69] Throughout July state-controlled channel NTV broadcast a multi-part documentary entitled "The Godfather" highlighting the suspicious disappearance of the opposition leaders Yury Zacharanka and Viktar Hanchar, businessman Anatol Krasouski and journalist Dzmitry Zavadski during the late 1990s.[163] Lukashenko called the media attack "dirty propaganda".[164]

His policies have been praised by some other world leaders. In response to a question about Belarus's domestic policies, President Hugo Chávez of Venezuela said "We see here a model social state like the one we are beginning to create."[165] The Chairman of the Chinese Standing Committee of National People's Congress Wu Bangguo noted that Belarus has been rapidly developing under Lukashenko.[166]

_7.jpg)

.jpg)

In 2015, Lukashenko sought to improve trade relations between Belarus and Latin America.[167]

Following the 2014 Syrian presidential election, President Lukashenko congratulated President Bashar al-Assad. His cable "expressed keenness to strengthen and develop bilateral relations between Belarus and Syria in all fields for the benefit of the two peoples."[168]

Belarus condemned the military intervention in Libya, and the foreign ministry stated that "The missile strikes and bombings on the territory of Libya go beyond Resolution 1973 of the UN Security Council and are in breach of its principal goal, ensuring safety of civilian population. The Republic of Belarus calls on the states involved with the military operation to cease, with immediate effect, the military operations which lead to human casualties. The settlement of the conflict is an internal affair of Libya and should be carried out by the Libyan people alone without military intervention from outside."[169] They have not recognized the National Transitional Council.

Upon hearing the news regarding the death of Muammar Gaddafi, President Alexander Lukashenko said "Aggression has been committed, and the country's leadership, not only Muammar Gaddafi, has been killed. And how was it killed? Well, if they had shot him in a battle, it's one thing, but they humiliated and tormented him, they shot at him, they violated him when he was wounded, they twisted his neck and arms, and then they tortured him to death. It's worse than the Nazis once did." He also condemned the current situation of Libya and was critical regarding the future of the country.[170][171]

Despite a historically good relationship with Russia, tensions between Lukashenko and the Russian government started showing in 2020.[172][173] On 24 January 2020, Lukashenko publicly accused Russian President Vladimir Putin of trying to make Belarus a part of Russia.[172] This led to Russia cutting economic subsidies for Belarus.[174] In July 2020, the relationship between Belarus and Russia was described as "strained" after 33 Russian military contractors were arrested in Minsk.[173] Lukashenko afterwards accused Russia of trying to cover up an attempt to send 200 fighters from a private Russian military firm known as the Wagner Group into Belarus on a mission to destabilize the country ahead of its 9 August presidential election.[175] On 5 August 2020, Russia's security chief Dmitry Medvedev warned Belarus to release the contractors.[174] Lukashenko also claimed Russia was lying about its attempts to use the Wagner Group to influence the upcoming election.[176]

Controversial statements

In 1995, Lukashenko was accused of making a remark which has been construed to be in praise of Adolf Hitler: "The history of Germany is a copy of the history of Belarus. Germany was raised from ruins thanks to firm authority and not everything connected with that well-known figure Hitler was bad. German order evolved over the centuries and attained its peak under Hitler."[177]

In October 2007, Lukashenko was accused of making antisemitic comments; addressing the "miserable state of the city of Babruysk" on a live broadcast on state radio, he stated: "This is a Jewish city, and the Jews are not concerned for the place they live in. They have turned Babruysk into a pigsty. Look at Israel—I was there and saw it myself ... I call on Jews who have money to come back to Babruysk."[178][179] Members of the US House of Representatives sent a letter to the Belarusian ambassador to the US, Mikhail Khvostov, addressing Lukashenko's comments with a strong request to retract them,[180] and the comments also caused a negative reaction from Israel.[181] Consequently, Pavel Yakubovich, editor of Belarus Today, was sent to Israel, and in a meeting with the Israel Foreign Ministry said that Lukashenko's comment was "a mistake that was said jokingly, and does not represent his positions regarding the Jewish people" and that he was "anything but anti-Semitic," and had been "insulted by the mere accusation."[182] The Belarusian Ambassador to Israel, Igor Leshchenya, stated that the president had a "kind attitude toward the Jewish people", and Sergei Rychenko, the press secretary at the Belarusian Embassy in Tel Aviv, said parts of Lukashenko's comments had been mistranslated.[183]

On 4 March 2012, two days after EU leaders (including openly gay German Foreign Minister Guido Westerwelle) had called for new measures to pressure Lukashenko over alleged human rights abuses in Belarus at a summit in Brussels, Lukashenko provoked diplomatic rebuke from Germany after commenting that it was "better to be a dictator than gay"[184] in response to Westerwelle having referred to him as "Europe's last dictator" during the meeting.[185][186]

Public opinion

Independent polling is tightly restricted in Belarus.[187] Surveys are monopolized by the government, which either does not publish its surveys or uses them for propagandistic purposes.[187][188]

According to a leaked internal poll, a third of the population had trust in Lukashenko.[187] The last credible public poll in Belarus was a 2016 poll showing approximately 30% approval for Lukashensko.[189]

Personal life

Family

Lukashenko married Galina Zhelnerovich, his high school sweetheart, in 1975. Later that year, his oldest son, Viktor, was born. Their second son, Dmitry, was born in 1980. Galina lives separately in the family's house in the village near Shklov. Though they are still legally married, Galina Lukashenko has been estranged from her husband since shortly after he became president.[190]

Lukashenko fathered a son, Nikolai, who was born in 2004. Though never confirmed by the government, it is widely believed that the child's mother is Irina Abelskaya—the two had an affair when she was Lukashenko's personal doctor.[191] It has been reported by Western observers and media that Nikolai, nicknamed "Kolya", is being groomed as Lukashenko's successor.[192][193] According to Belarusian state media, these speculations were dismissed by Lukashenko, who also denied that he would remain in office for a further thirty years—the time Nikolai will become eligible to stand for election and succeed him.[194]

Hobbies

Lukashenko believes that the president should be a conservative person and avoid using modern electronic gadgets such as an iPad or iPhone.[196] He used to play bayan and football, but abandoned both during his presidency.[197] He is a keen skier and ice hockey forward, who played exhibition games alongside international hockey stars.[198][199][200] His two elder sons also play hockey, sometimes alongside their father.[201]

Lukashenko started training in cross-country running as a child, and in the 2000s still competed at the national level.[202]

Orders and honors

- Winner of the international premium of Andrey Pervozvanny "For Faith and Loyalty" (1995)[203]

- The Order of José Marti (Cuba, 2000)[204]

- Order of the Revolution (Libya, 2000)[205]

- Special prize of the International Olympic Committee "Gates of Olympus" (2000)[206]

- Order "For Services to the Fatherland", 2nd Class (Russia, 2001)[207]

- Honorary citizen of Yerevan, Armenia (2001)[208]

- Order of St. Dmitry Donskoy, First Degree (2005)[209]

- Medal of the International Federation of Festival Organizations "For development of the world festival movement" (2005)[210]

- Order of St. Cyril (by the Belarusian Orthodox Church) (2006)[211]

- Honorary Diploma of the Eurasian Economic Community (2006)[212]

- Order of St. Vladimir, First Degree (2007)[213]

- Keys to the City of Caracas, Venezuela (2010)[214]

- Order of Distinguished Citizen (Caracas, Venezuela; 2010)[215]

- Order of the Republic of Serbia (2013)[216][217]

- Presidential Order of Excellence (Georgia, 2013)[218]

- Order of Alexander Nevsky (2014)[219]

- Order of Nazarbayev (2019)[220][221]

References

- "Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya calls for end to violence in Belarus as election fallout continues". Sky News. 14 August 2020. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- "Belarus opposition candidate declares victory | NHK WORLD-JAPAN News". www3.nhk.or.jp.

- "Exiled leader calls weekend of protests in Belarus". 14 August 2020 – via www.bbc.co.uk.

- https://gordonua.com/news/worldnews/tihanovskaya-gotovitsya-obyavit-sebya-pobeditelnicey-vyborov-v-belarusi-press-sekretar-1513911.html

- "Lukashenko Earns $31,242". The Moscow Times. 22 November 2010. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- "Лукашенко рассказал о своем воинском звании и наградах". EADaily. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- "Belarus – Government". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. 18 December 2008. Archived from the original on 10 December 2008. Retrieved 26 December 2008.

- Office of the Press secretary (20 October 2004). "Statement on the Belarus Democracy Act of 2004". The White House. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- "Profile: Alexander Lukashenko". BBC News. BBC. 9 January 2007. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

'..an authoritarian ruling style is characteristic of me [Lukashenko]'

- Levitsky, Steven; Way, Lucan A. (2010). "The Evolution of Post-SovietCompetitive Authoritarianism". Competitive Authoritarianism: Hybrid Regimes after the Cold War. Problems of International Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 203. ISBN 9781139491488. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

Unlike his predecessor, Lukashenka consolidated authoritarian rule. He censored state media, closed Belarus's only independent radio station [...].

- Jones, Mark P. (2018). "Presidential and Legislative Elections". The Oxford Handbook of Electoral Systems. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190258658.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780190258658-e-23. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

unanimous agreement among serious scholars that... Lukashenko's 2015 election occurred within an authoritarian context.

- Levitsky, Steven (2013). Competitive authoritarianism: hybrid regimes after the Cold War. Cambridge University Press. pp. 4, 9–10, 21, 70. ISBN 978-0-521-88252-1. OCLC 968631692.

- Crabtree, Charles; Fariss, Christopher J.; Schuler, Paul (2016). "The presidential election in Belarus, October 2015". Electoral Studies. 42: 304–307. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2016.02.006. ISSN 0261-3794.

- "Belarus strongman Lukashenko marks 25 years in power | DW | 10 July 2019". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- "Belarus leader dismisses democracy even as vote takes place". AP NEWS. 17 November 2019. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- Rausing, Sigrid (7 October 2012). "Belarus: inside Europe's last dictatorship". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- "World Report 2020: Rights Trends in Belarus". Human Rights Watch. 10 December 2019. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

- "Human rights by country – Belarus". Amnesty International Report 2007. Amnesty International. 2007. Archived from the original on 12 December 2007. Retrieved 22 December 2007.

- "COUNCIL DECISION 2012/642/CFSP concerning restrictive measures against Belarus". Official Journal of the European Union. Council of the European Union. 15 October 2012. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- Department of the Treasury (5 December 2012). "Belarus Sanctions". Government of the United States. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- Скандал! Лукашенко изменил биографию (видео и фото) » UDF.BY | Новости Беларуси | Объединённые демократические силы Archived 24 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine. UDF.BY. Retrieved 13 April 2011.

- Официальный интернет-портал Президента Республики Беларусь/Биография. President.gov.by (11 May 1998). Retrieved 13 April 2011.

- Малишевский, Виктор; Ульяна Бобоед (15 August 2003). В Минск из Канады летит троюродный племянник Лукашенко. Комсомольской Правды в Белоруссии (in Russian). Archived from the original on 31 July 2008. Retrieved 28 December 2008.

- "Alexander Lukashenko: Dictator with a difference". The Daily Telegraph. London. 25 September 2008. Archived from the original on 26 September 2008. Retrieved 26 September 2008.

- ""Рослая, сильная, с характером". В Александрии похоронили мать Лукашенко". Tut.By. 26 May 2015.

- "President Visits New Swimming Complex in Minsk". President of the Republic of Belarus. 20 September 2007. Archived from the original on 30 November 2012. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- "Biographical profile of the President". President of the Republic of Belarus. Archived from the original on 17 October 2007. Retrieved 17 October 2007.

- "Александр Лукашенко, биография, новости, фото – узнай вce!" (in Russian). Unayvse. 30 August 2017.

- Spector, Michael (25 June 1994). "Belarus Voters Back Populist in Protest at the Quality of Life". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 October 2007.

- Savchenko, Andrew (15 May 2009). "Borderland Forever: Modern Belarus". Belarus: A Perpetual Borderland. Brill Academic Pub. p. 179. ISBN 978-9004174481.

- Jeffries, Ian (4 March 2004). "Belarus". The Countries of the Former Soviet Union at the Turn of the Twenty-First Century: The Baltic and European States in Transition. Routledge Studies of Societies in Transition. Routledge. p. 266. ISBN 978-0415252300.

- White, Stephen; Korosteleva, Elena; John, Löwenhardt (2005). "Ronald J. Hill". Postcommunist Belarus. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 6–7.

- Country Studies Belarus – Prelude to Independence. Library of Congress. Retrieved 21 March 2007.

- Alyaksandr Lukashenka in: Encyclopædia Britannica Online, 2009.

- Central Election Commission of the Republic of Belarus 1995 Referendum Questions (in Russian) Archived 18 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Babkina, Marina (19 November 1996). "Lukashenko Defies Impeachment Move". AP New Archives. Associated Press. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- "Belarus: Lukashenko wins referendum to extend mandate". www.euractiv.com. 18 October 2004. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- Центральной комиссии Республики Беларусь по выборам и проведению республиканских референдумов. rec.gov.by (1996)

- Bekus, Nelly (2012). Struggle over Identity: The Official and the Alternative "Belarusianness". Central European University Press. pp. 103–4. ISBN 978-9639776685.

- Wilson, Andrew (6 December 2011). "Belarus: The Last European Dictatorship". Yale University Press.

- U.S. Relations With Belarus. US Department of State. 19 February 2014.

- Poland's Role in the Development of an 'Eastern Dimension' of the European Union – Andreas Lorek. Retrieved 9 January 2013.

- "Belarus appoints new national bank chief". BBC. 21 March 1998.

- Maksymiuk, Jan (22 July 1998). "Eu punishes Belarusian leadership". RFE/RL Newsline, Vol. 2, No. 139, 98-07-22. From: Radio Free Europe/Radio Libert. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- "Poor Showing Reportedly Riles Ruler of Belarus". The Washington Post. Associated Press. 20 February 1998. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- "The Statement of the Belarus President Alexander Lukashenko". Serbia Info News. Ministry of Information of the Republic of Serbia. 15 April 1999. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- "Contemporary Belarus: Between Democracy and Dictatorship" (London: RoutledgeCurzon, 2003), with R. Marsh and C. Lawson

- "Lukashenko claims victory in Belarus election". USA Today. 10 September 2001. Retrieved 17 October 2007.

- Standish, M J A (11 January 2006). "Editor's notes." Jane's Intelligence Digest.

- "Saddam aides may flee to Belarus: report". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 24 June 2003. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- "Profile: Europe's last dictator?". BBC News. 10 September 2001. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- "Belarus Foreign Minister Sergei Martynov interview for The Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung – Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Belarus". Mfa.gov.by. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- "Observers deplore Belarus vote". BBC News. 18 October 2004. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- Collin, Matthew (3 October 2005). "Belarus opposition closes ranks". BBC News. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- Staff writer (20 March 2006). "Gallup/Baltic Surveys announces impossibility of independent and reliable exit polls under present conditions in Belarus". Charter'97. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- "Incumbent Declared Winner of Belarus Vote". Athens Banner-Herald. Associated Press. 20 March 2006. Archived from the original on 22 June 2013. Retrieved 13 September 2012.

The gathering was the biggest the opposition had mustered in years, reaching at least 10,000 before it started thinning out, according to AP reporters' estimates.

- Staff Writer (21 March 2006). "CIS, OSCE observers differ on Belarus vote". People's Daily. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

Election observers from the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) declared the Belarus presidential vote open and transparent on Monday. The Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) did not assess the election positively.

- Kramer, David (21 March 2006). "Ballots on the Frontiers of Freedom: Elections in Belarus and Ukraine". United States Department of State. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- "West slams Belarus crackdown". CNN. 24 March 2006. Archived from the original on 28 April 2007. Retrieved 17 October 2007.

- Лукашенко: Последние выборы мы сфальсифицировали (in Russian). BelaPAN. 23 November 2006. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- "Poland, Belarus & Ukraine Report". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 28 November 2006. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- Staff writer (28 February 2007). "Rightist Group Promote Belarus Dictator Lukashenko as Russian Presidential Candidate". MosNews. Archived from the original on 28 February 2007. Retrieved 11 July 2007.

- "Belarus clean sweep poll 'flawed'", BBC News, 29 September 2008.

- "CIS: Monitoring The Election Monitors". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 2 April 2005. Retrieved 24 September 2009.

- "CIS observers: Belarus' elections meet international standards" (in Russian). National Center of Legal Information of the Republic of Belarus. 29 September 2008. Archived from the original on 17 June 2009. Retrieved 12 October 2008.

- "Opposition gewinnt keinen einzigen Sitz – Proteste in Weißrussland". Der Spiegel (in German). 29 September 2008. Archived from the original on 3 October 2008. Retrieved 30 September 2008.

- Belarus leader meets Pope in landmark trip. Agence France-Presse. Google News (27 April 2009). Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- Belarus sets date of presidential election for 19 December 2010 Archived 6 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. News.belta.by (14 September 2010). Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- RFE/RL. Has Moscow Had Enough Of Belarus's Lukashenka?. (19 July 2010).

- "'Dirty tricks' taint Belarus vote". Al Jazeera. 18 December 2010. Archived from the original on 20 December 2010. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- "Activist fears over Belarus vote". Al Jazeera. 19 December 2010. Archived from the original on 23 December 2010. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- "'Hundreds of protesters arrested' in Belarus". BBC News. 20 December 2010. Archived from the original on 21 December 2010. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- "Police break up opposition rally after Belarus poll". BBC News. 19 December 2010. Archived from the original on 19 December 2010. Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- "Two Belarus presidential candidates say attacked by special forces". RIA Novosti. 19 December 2010. Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- "Спецназ избил двух кандидатов в президенты Белоруссии; Некляев без сознания". Gazeta.ru. 19 December 2010. Retrieved 19 December 2010.

- "Protesters try to storm government HQ in Belarus". BBC News. 20 December 2010. Archived from the original on 20 December 2010. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- "Belarus president re-elected". Al Jazeera. 20 December 2010. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- "Protesters try to storm government HQ in Belarus". BBC. 20 December 2010. Archived from the original on 26 January 2011. Retrieved 11 January 2011.

- "Belarus' Lukashenko re-elected, police crackdown". Reuters. 19 December 2010. Archived from the original on 23 December 2010. Retrieved 11 January 2011.

- "Hundreds arrested in Belarus protests". Financial Times. 20 December 2010. Archived from the original on 22 January 2011. Retrieved 11 January 2011.

- "BBC News – Leading Belarus dissident Sannikov gets UK asylum". Bbc.co.uk. 26 October 2012. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- "Center for Public Scholarship :: Alexander Otroschenkov". Newschool.edu. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- "RIGHTS AND DEMOCRACY | Media Advisory – Exiled Belarusian presidential candidate Ales Michalevic to visit Toronto". Newswire.ca. 23 November 2011. Archived from the original on 28 March 2014. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (1 June 2011). "Jailed Belarusian opposition leader not allowed to see wife, father". Refworld. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- Foreign Policy and Security Research (15 November 2011). "Swedish PEN awards prize to Uladzimir Nyaklyayew". Forsecurity.org. Archived from the original on 28 March 2014. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- Taylor, Jerome (15 February 2013). "Captive Belarusian journalist Irina Khalip allowed to visit husband in Britain – Europe – World". The Independent. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- Interview by Stephen Browne (21 February 2011). "BELARUSIAN DISSIDENT JAROSLAV ROMANCHUK". TheAtlasSphere.com. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- СООБЩЕНИЕ об итогах выборов Президента Республики Беларусь (PDF) (in Russian). Central Election Commission of Belarus. 5 January 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 January 2011. Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- "Belarus vote count 'flawed' says OSCE | RIA Novosti". RIA Novosti. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- "Belarus still has considerable way to go in meeting OSCE commitments, despite certain improvements, election observers say". OSCE. 20 December 2010. Archived from the original on 23 December 2010. Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- Lukashenko the Loser. Joint letter of Foreign Ministers of Germany, Sweden, Poland and Czech Republic. NYTimes (24 December 2010)

- Lukashenko Growls at Inauguration, The Moscow Times (24 January 2011)

- "32 foreign diplomats to attend Lukashenko inauguration | World | RIA Novosti". En.rian.ru. 20 January 2011. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- Dempsey, Judy (2 January 2011). U.S. and E.U. Join to Show Support for Belarus Opposition. New York Times

- The European Union has News for Belarus’s Alexander Lukashenko: You’re Grounded. macleans.ca (17 February 2011).

- COUNCIL DECISION 2011/69/CFSP. Official Journal of the European Union. (31 January 2011).

- Jacopo Dettoni; Wendy Atkins (15 August 2019). "What the BRI brings to Belarus and Great Stone Industrial Park". fDi Intelligence. Financial Times. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- Simes, Dimitri (16 July 2020). "Unrest threatens China's Belt and Road 'success story' in Belarus". Nikkei Asian Review. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- "Belarus' Lukashenko at his swearing-in ceremony rejects calls for reforms". Fox News. 6 November 2015. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- "NATO Nervous As Russia, Belarus Team Up For Cold-War-Style War Games". Npr.org. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- "Russian War Games Aim To Head Off Another Color Revolution". The Washington Post.

- "Belarus president fires prime minister after corruption scandal". Agence France-Presse. 18 August 2018. Retrieved 13 February 2020 – via theguardian.com.

- "II European Games 2019 Directorate set up". National Olympic Committee of the Republic of Belarus. 12 May 2017. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- "President Aleksandr Lukashenko Emphasises Significance of European Games For Belarus". Around the Rings. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- "European Games open in Belarus". TRT World. 22 June 2019. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

- "Военный парад в честь 75-летия освобождения: Беларусь отметила День независимости". TUT.BY. 3 July 2019. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- "Alexander Lukashenko meets with former President of Kyrgyzstan Kurmanbek Bakiyev". tvr.by. 6 August 2019.

- "Lukashenka angers Kyrgyz Foreign Ministry". belsat.eu. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- "В Министерство иностранных дел КР был вызван Временный Поверенный в делах Посольства Республики Беларусь в Кыргызской Республике С.Иванов – Министерство иностранных дел Кыргызской Республики". mfa.gov.kg (in Russian).

- "Kyrgyz FM Summons Belarusian Ambassador Over Lukashenka-Bakiev Meeting". rferl.org. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- "Новости | Официальный интернет-портал Президента Республики Беларусь". president.gov.by. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- "John Bolton's Belarus trip stirs threat to Putin". Washington Examiner. 30 August 2019. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- "Bolton Says U.S.-Belarus Dialogue Necessary, Despite 'Significant Issues'". rferl.org. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- "Why National Security Adviser John Bolton's Trip to Belarus Matters". The Daily Signal. 29 August 2019. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- "Lukashenko ends his European isolation". amp.dw.com. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- "Isolated Belarus looks towards Europe despite Russian overtures". aljazeera.com. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- "Belarus' leader visits Austria, pushes for closer EU ties". WKMG. 12 November 2019. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- "About Hungary – Statement by Prime Minister Viktor Orbán following his talks with Alexander Lukashenko, President of the Republic of Belarus". abouthungary.hu. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- "Orbán urges end to EU sanctions on Belarus". 6 June 2020. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- "Lukashenko: Belarus will not cancel Victory Day celebrations". eng.belta.by. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- "Belarus election: Clashes after poll predicts Lukashenko re-election". BBC News. 10 August 2020.

- "US 'deeply concerned' over election in Belarus". The Hill. 10 August 2020.

- Jones, Mark P. (2018). Herron, Erik S; Pekkanen, Robert J; Shugart, Matthew S (eds.). "Presidential and Legislative Elections". The Oxford Handbook of Electoral Systems. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190258658.001.0001. ISBN 9780190258658. Retrieved 21 May 2020.

unanimous agreement among serious scholars that... Lukashenko's 2015 election occurred within an authoritarian context.

- "Lukashenka vs. democracy: Where is Belarus heading?". AtlanticCouncil. 10 August 2020. Archived from the original on 12 August 2020.

However, the vote was marred by allegations of widespread fraud. These suspicions appeared to be confirmed by data from a limited number of polling stations that broke ranks with the government and identified opposition candidate Svyatlana Tsikhanouskaya as the clear winner.

- "Belarus election: Exiled leader calls weekend of 'peaceful rallies'". BBC News. 14 August 2020. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- "Belarus opposition candidate declares victory | NHK WORLD-JAPAN News". www3.nhk.or.jp.

- https://en.interfax.com.ua/news/general/681364.html

- https://apnews.com/2654151658e4a01e36248a71a3911324

- "Tweet of Linas Linkevicius (@LinkeviciusL)". Twitter. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- Лукашенко планирует бегтсво в Россию. searchnews (in Russian). 15 August 2020.

- "Bloomberg узнал о планах окружения Лукашенко в случае его свержения". Газета.Ru.

- https://tass.com/world/1190499

- "NOC RB". National Olympic Committee of the Republic of Belarus. 2002. Archived from the original on 17 October 2007. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- "Lukashenko's first term as president". Brussels Review. 16 March 2006. Archived from the original on 20 October 2007. Retrieved 21 October 2007.

- "Belarus – Industry". Country Studies. Library of Congress. 1995. Retrieved 8 October 2007.

- Karatnycky, Adrian; Alexander J. Motyl; Amanda Schnetzer (2001). Nations in Transit, 2001. Transaction Publishers. p. 101. ISBN 0-7658-0897-8.

- "Lukashenko Sworn in as Belarusian President". People's Daily. 21 September 2001. Retrieved 17 October 2007.

- Vadzim Smok. Belarusian Identity: the Impact of Lukashenka’s Rule // Analytical Paper. Ostrogorski Centre, BelarusDigest, 9 December 2013.

- Belarus has an identity crisis // openDemocracy

- Галоўная бяда беларусаў у Беларусі — мова // Novy Chas (in Belarusian)

- Аляксандар Русіфікатар // Nasha Niva (in Belarusian)

- "The official internet-portal of the President of the Republic of Belarus/State Policy". President.gov.by. 11 May 1998. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- "Labour". Belstat.gov.by. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- "Belarus | Data". World Bank. 30 November 2012. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- "National Bank to peg Belarusian ruble to foreign currency system in 2009 – Economy / News / Belarus Belarusian Belarus today | Minsk BELTA – Belarus Belarusian Belarus today | Minsk BELTA". News.belta.by. 17 June 2008. Archived from the original on 19 February 2013. Retrieved 9 January 2013.

- "Belarus Plans New Ruble Devaluation | RIA Novosti". RIA Novosti. 30 July 2012. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- "Ruble devaluation spreads panic among Belarusians". People's Daily. 26 May 2011. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- "Belarus eyes new IMF loans – Xinhua | English.news.cn". Xinhua News Agency. 30 October 2012. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- "BBC News – RBS agrees to end work for Belarus". BBC. 29 August 2011. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- Potupa, Aleksandr (2 May 1997). "Lukashism" has the potential to spread beyond Belarus. Prism Volume: 3 Issue: 6.

- Dubina, Yuras (1998). "A museum to commemorate victims of communism". Belarus Now. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

Belarusian MPs propose to dedicate a section in the future museum to Lukashism

- "Beware of Lukashism!". Zubr. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- Pavlov, Nikolai (27 March 2006). "Belarus protesters go on trial as new rallies loom". Belarus News and Analysis. Archived from the original on 9 October 2006. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- The Belarus Democracy Act of 2004. house.gov. 20 October 2004.

- Staff writer (9 January 2007). "Profile: Alexander Lukashenko". BBC News. Archived from the original on 17 October 2007. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- Dixon, Robyn (27 March 2020). "No lockdown here: Belarus's strongman rejects coronavirus risks. He suggests saunas and vodka". The Washington Post. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- Grez, Matias (29 March 2020). "Football is shut down across Europe due to the coronavirus, but in Belarus it's business as usual". CNN. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- Khurshudyan, Isabelle (2 May 2020). "Coronavirus is spreading rapidly in Belarus, but its leader still denies there is a problem". The Washington Post. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- Haltiwanger, John. "Europe's last dictator got COVID-19 after telling people they could avoid it by drinking vodka and going to the sauna". Business Insider. Retrieved 28 July 2020.

- Montgomery, Blake (28 July 2020). "Belarus President, Who Said Vodka Would Cure the Coronavirus, Says He Tested Positive and Recovered". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- Czachor, Rafał (2011) Polityka zagraniczna Republiki Białoruś w latach 1991–2011. Studium politologiczne, Wydawnictwo DWSPiT, Polkowice, p. 299, ISBN 978-83-61234-72-2

- Makhovsky, Andrei. "Belarus leader calls for dialogue with European Union". Reuters. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- RFE/RL. Is Lukashenka In The Kremlin's Crosshairs?. (8 July 2010).

- RFE/RL. Lukashenka Calls Russian Media Attacks 'Dirty Propaganda' . (29 July 2010).

- "Chavez forges ties with Belarus". BBC News. 25 July 2005. Archived from the original on 8 March 2007. Retrieved 17 October 2007.

- "China Praises Lukashenko for His Successful Opposition to the West". The China Times. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- "Lukashenko highlights Belarus' cooperation with Latin America". Belarusian News. 25 June 2015. Archived from the original on 8 July 2015. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- "President Assad receives Congratulations from the President of Belarus: Confidence in Syria Elimination of Current Crisis". Syriatimes.com.

- "Statement released by the Foreign Ministry in connection with the missile strikes and bombings on Libya". Mfa.gov.by. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- "Lukashenko outraged by Gaddafi's treatment". Kyivpost.com. 4 November 2011.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 4 July 2012. Retrieved 25 December 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Lukashenka Accuses Moscow Of Pressuring Belarus Into Russian Merger". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- Welle (www.dw.com), Deutsche. "Belarus: Lukashenko accuses Russian mercenaries, critics of plotting attack | DW | 31.07.2020". DW.COM. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- "Russia warns Belarus will pay price for contractors' arrests". Stars and Stripes. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- "Belarusian President Accuses Russia Of Trying To Cover Up Vagner Group Election Plot". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- "Belarus ruler says Russia lying over 'mercenaries'". 4 August 2020. Retrieved 9 August 2020 – via www.bbc.com.

- "Bigotry in Belarus". The Jerusalem Post. 20 October 2007. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- In 1926 there were 21,558 Jews in Babruysk or 42% of the town's population; by 1989, they numbered just over 4% and by 1999 a mere 0.6%. See Jewish Heritage Research Group in Belarus

- Sofer, Ronny (18 October 2007). "Belarus president attacks Jews". Ynet News. Yedioth Internet. Archived from the original on 20 October 2007. Retrieved 19 October 2007.

- "Kirk-Hastings Letter Calls on Belarusian President to Apologize for Blatantly Anti-Semitic Remarks". Office of Rep. Mark Steven Kirk. 2007. Archived from the original on 3 November 2007. Retrieved 1 November 2007.

- "FM Livni condemns anti-Semitic remarks made by Belarusian President". Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 18 October 2007. Archived from the original on 21 October 2007. Retrieved 19 October 2007.

- "News in Brief". Haaretz. 31 October 2007. Retrieved 1 November 2007.

- Herb Keinon (25 October 2007). "Belarus to send envoy to Israel". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- Germany rebukes Lukashenko over anti-gay comment | euronews, world news. Euronews.com (5 March 2012). Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- "Belarus's Lukashenko: "Better a dictator than gay"". Berlin. Reuters. 4 March 2012.

...German Foreign Minister's branding him 'Europe's last dictator'

- World News – 'Better a dictator than gay,' Belarus President Alexander Lukashenko says. MSN.com (5 March 2012). Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- Higgins, Andrew (22 June 2020). "Political Grip Shaky, Belarus Leader Blames Longtime Ally: Russia". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- Shraibman, Artyom. "The House That Lukashenko Built: The Foundation, Evolution, and Future of the Belarusian Regime". Carnegie Moscow Center. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- "Belarus presidential election: Will the lights go out on Lukashenko?". euronews. 12 June 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ЛЯШКЕВИЧ, Анна. "Галина Лукашенко: Саша – необыкновенный человек". Комсомольская правда в Белоруссии (in Russian). БелаПАН. Retrieved 26 December 2008.

- Parfitt, Tom (6 April 2009). "Belarus squirms as son follows in dictator's steps". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 8 December 2009.

- Walker, Shaun (29 June 2012). "Who's that boy in the grey suit? It's Kolya Lukashenko – the next dictator of Belarus..." The Independent. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- Haddadi, Anissa (29 June 2012). "The Belarus Boy Wonder: Nikolai Lukashenko, 7, Anointed to become President". International Business Times. IBTimes Co. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- "Lukashenko denies reports he is grooming Nikolai as his successor". Belarusian News. BELTA. 22 October 2012. Archived from the original on 15 August 2014. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- "Belarus president visits Vatican". BBC News. 27 April 2009. Retrieved 26 June 2010.

- Д.Медведев объяснил, почему заменил iPad блокнотом Archived 7 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine. rbc.ru. 15 May 2013.

- Александр Лукашенко разучился играть на баяне. km.ru. 15 January 2013.

- Ветераны «Сборной звезд мира» проведут товарищескую игру. sports.ru. 12 December 2008.

- Лукашенко – звезда мирового хоккея. sports.ru. 20 December 2008.

- Лукашенко забил шайбу. Команда Президента Беларуси играет и выигрывает в Казахстане 10:8. CentrAsia. 22 December 2004.

- Президент-хоккей Александра Лукашенко. ng.ru. 1 October 2003.

- Александр Лукашенко выиграл лыжные соревнования. vsesmi.ru. 3 March 2007.

- Лауреаты Международной премии Андрея Первозванного "За Веру и Верность". 1993–2005 годы (in Russian). Фонд Святого Всехвального апостола Андрея Первозванного. 1995. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- А.Г. Лукашенко награжден орденом Хосе Марти. Вечерний Минск (in Russian). 5 September 2000. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- Белоруссия. Zatulin.ru (in Russian). 15 November 2000. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- Олимпийский приз для Беларуси (in Russian). Пресс-центр НОКа. 12 June 2006. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- "Президент России". Archive.kremlin.ru. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- "Honorary Citizens of Yerevan" (in Russian). City of Yerevan, Armenia. Archived from the original on 16 January 2008. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- Korobov, Pavel (11 May 2005). Патриарх наградил Александра Лукашенко. Religare.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- Президент Беларуси Александр Лукашенко удостоен медали "За развитие мирового фестивального движения" (in Russian). Embassy of the Republic of Belarus in the Russian Federation. 18 July 2005. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- Александр Лукашенко награжден орденом Белорусской Православной Церкви (in Russian). Maranatha. 26 September 2006. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- В Минске прошло заседание Межгосударственного Совета ЕврАзЭС (in Russian). President of the Republic of Belarus. 23 June 2006. Archived from the original on 10 November 2007. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- "Александр Лукашенко награжден орденом Святого Владимира I степени". Патриархия.ru (in Russian). 5 June 2007. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- "Presidente Chávez se reúne con su par bielorruso Lukashenko". Mre.gov.ve. Archived from the original on 24 December 2012. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- "Jorge Rodríguez | Alcalde de Libertador " " Alcalde Jorge Rodríguez entrega llaves de la Ciudad de Caracas al Presidente Lukashenko". Jorgerodriguez.psuv.org.ve. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- "Ukazi o odlikovanjima". Predsednik.rs (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 18 June 2013. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- "Meeting with President Tomislav Nikolić of the Republic of Serbia". President.gov.by. Archived from the original on 10 April 2013. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- "State Awards Issued by Georgian Presidents in 2003–2015". Institute for Development of Freedom of Information. 10 May 2018. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- "Putin signed the decree about Lukashenko's rewarding with the Order of Alexander Nevsky". itar-tass.com. 30 August 2014.

- Первый Президент Казахстана встретился с Президентом Республики Беларусь Александром Лукашенко (in Kazakhstani), 28 March 2019. Accessed on 10 October 2019.

- "Nursultan Nazarbayev presents Order of Yelbasy to Alexander Lukashenko". inform.kz. 28 May 2019. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

External links

- President's official site (in English, Russian, Belarusian, and Polish)

- BBC – Profile: Alexander Lukashenko

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Myechyslaw Hryb as Chairperson of the Supreme Soviet of Belarus |

President of Belarus 1994–present |

Incumbent |