West India Docks

The West India Docks are a series of three docks on the Isle of Dogs in London, England the first of which opened in 1802. The docks closed to commercial traffic in 1980 and the Canary Wharf development was built on the site.[1]

| West India Docks | |

|---|---|

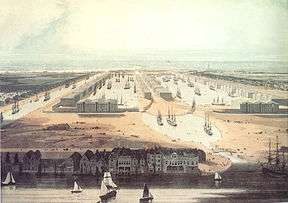

An 1802 painting of the completed docks. The canal to the left of the painting was later closed and became a third dock. The view is looking west towards the City of London. | |

| Location | London |

| Coordinates | 51.50347°N 0.01722°W |

| Built | 1802 |

| Built for | West India Dock Company |

| Architect | Robert Milligan |

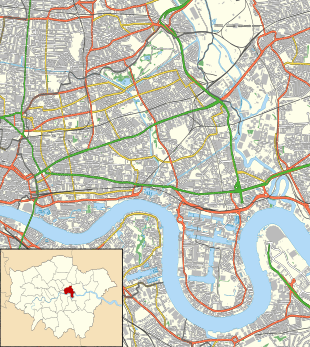

Location of West India Docks in London Borough of Tower Hamlets | |

History

.jpg)

Early history

Robert Milligan (c. 1746-1809) was largely responsible for the construction of the West India Docks. Milligan was a wealthy West Indies slave-owner, merchant, slave-factor and ship owner, who returned to London having previously managed his family's Jamaica sugar plantations.[2] Outraged at losses due to theft and delay at London's riverside wharves, Milligan headed a group of powerful businessmen, including the chairman of the London Society of West India Planters and Merchants, George Hibbert, a slave-owner, merchant, politician,and ship-owner[3], who promoted the creation of a wet dock circled by a high wall. The group planned and built West India Docks, lobbying Parliament to allow the creation of a West India Dock Company. Milligan served as both Deputy Chairman and Chairman of the West India Dock Company. The Docks were authorised by the West India Dock Act 1799 (39 Geo. 3, c. lxix).[1]

The Docks were constructed in two phases. The two northern docks were constructed between 1800 and 1802 for the West India Dock Company to a design by leading civil engineer William Jessop (John Rennie was a consultant, and Thomas Morris, Liverpool's third dock engineer, was also involved; Ralph Walker was appointed resident engineer),[4] and were the first commercial wet docks in London. British Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger and Lord Chancellor Lord Loughborough were assisted in the foundation stone ceremony on 12 July 1800 by Milligan and Hibbert.[5] The docks were formally opened on 27 August 1802 when the unladen Henry Addington was hauled in by ropes. Echo, a ship laden with cargo from the West Indies, followed.[6] For the following 21 years all vessels in the West India trade using the Port of London were compelled to use the West India docks by a clause in the Act of Parliament that had enabled their construction.[7]

The southern dock, the South West India Dock, later known as South Dock, was constructed in the 1860s, replacing the unprofitable City Canal, built in 1805.[Note 1] The City of London Corporation acquired the Company in 1829. In 1909 the Port of London Authority (PLA) took over the West India Docks, along with the other enclosed docks from St Katharines to Tilbury.[8]

From 1960 to 1980, trade in the docks declined to almost nothing. There were two main reasons. First, the development of the shipping container made this type of relatively small dock inefficient, and the dock-owners were slow to embrace change. Second, the manufacturing exports which had maintained the trade through the docks dwindled and moved away from the local area. The docks were closed in 1981.[9]

Re-development

After the closure of the upstream enclosed docks, the area was regenerated as part of the Docklands scheme, and is now home to the developments of Canary Wharf. The early phase one buildings of Canary Wharf were built out over the water, reducing the width of the north dock and middle dock. Canary Wharf tube station was constructed within the middle dock in the 1990s.[10] Part of the original dock building was converted for use as the Museum of London Docklands in 2003.[11][12]

The Crossrail Place development was completed in May 2015[13] and the Canary Wharf Crossrail station below it was completed in September 2015.[14]

Layout

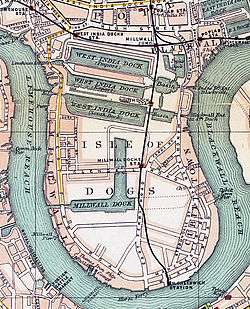

The original docks consisted of an Import Dock of 30 acres (120,000 m2) of water, later named North Dock, and an Export Dock of 24 acres (97,000 m2), later named Middle Dock. Between them, the docks had a combined capability to berth over 600 vessels. Locks and basins at either end of the Docks connected them to the river Thames. These were known as Blackwall Basin and Limehouse Basin, not to be confused with the Regent's Canal Dock also known as Limehouse Basin. To avoid congestion, ships entered from the (eastern) Blackwall end; lighters entered from the Limehouse end to the west. A dry dock for ship repairs was constructed connecting to Blackwall Basin. Subsequently, the North London Railway's Poplar Dock was also connected to Blackwall Basin.[15]

The Docks' design allowed a ship arriving from the West Indies to unload in the northern dock, sail round to the southern dock and load up with export cargo in a fraction of the time it had previously taken in the heavily congested and dangerous upper reaches of the Thames. Around the Import Dock a continuous line of five-storey warehouses was constructed, designed by architect George Gwilt and his son, also named George.[16] The Export Dock needed fewer buildings as cargo was loaded upon arrival. To protect against theft, the whole complex was surrounded by a brick wall 20 ft (6.1 m) high.[17]

The three docks were initially separate, with the two northern docks interconnected only via the basin at each end, and South Dock connected via a series of three basins at the eastern end. Railway access was very difficult. Under PLA control, cuts were made to connect the three docks into a single system, and the connections to the Thames at the western end were filled, along with the Limehouse basin and with it the western connection between the two northern docks. This allowed improved road and rail access from the north and west. South Dock was also connected to the north end of Millwall Dock, its enlarged eastern lock becoming the only entrance from the Thames to the whole West India and Millwall system.[18]

See also

Notes and references

Notes

- The City Canal had been constructed across the Isle of Dogs just to the south of West India Docks. The aim to provide a short cut for sailing ships, to save them travelling around the bottom of the Isle of Dogs to access the wharves in the upper reaches of the river; if winds were unfavourable, this journey could take some time. However, access to the canal was determined by the state of the tide, fees were expensive, and the transit slow.

References

- "History of the Port of London pre 1908". Port of London Authority. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- "London slavery statue removed from outside museum". BBC News. 9 June 2020. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- "Summary of Individual | Legacies of British Slave-ownership". www.ucl.ac.uk. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- Skempton, A.W. (2002) A Biographical Dictionary of Civil Engineers in Great Britain and Ireland, pp. 757-758

- West India Docks, The Times 14 July 1800 p.3

- The Morning Chronicle 28 August 1802

- West India Company Notice, The Morning Post and Gazetteer 31 Dec 1802

- "The Port of London". The Times (38921). 31 March 1909. p. 10. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- "History". London's Royal Docks. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- Mitchell, Bob (2003). Jubilee Line Extension: From Concept to Completion. ICE Publishing. p. 145. ISBN 978-0727730282.

- Sara Wajid (9 November 2007). "London, Sugar & Slavery Opens At Museum In Docklands". Culture24.org. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- Emma Midgley (23 May 2003). "MGM 2003 - A Capital Addition, Museum In Docklands Now Open". Culture24.org. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- Curtis, Nick (14 May 2015). "Norman conquest: Lord Foster's Crossrail Place garden". London Evening Standard. UK. Retrieved 26 July 2015.

- "Norman conquest: Lord Foster's Crossrail Place garden". The Standard. 14 May 2015. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

- 'Poplar Dock: Historical development', Survey of London: volumes 43 and 44: Poplar, Blackwall and Isle of Dogs (1994), pp. 336-341. URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=46502. Date accessed: 22 October 2007.

- Gwilt design Archived 19 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine accessed 8 February 2007

- 'The West India Docks: Security', in Survey of London: Volumes 43 and 44, Poplar, Blackwall and Isle of Dogs, ed. Hermione Hobhouse (London, 1994), pp. 310-313. British History Online URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vols43-4/pp310-313 accessed 30 November 2019

- 'The West India Docks: Historical development', Survey of London: volumes 43 and 44: Poplar, Blackwall and Isle of Dogs (1994), pp. 248-268. URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=46494. Date accessed: 22 October 2007.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to West India Docks. |