Water of crystallization

In chemistry, water(s) of crystallization or water(s) of hydration are water molecules that are present inside crystals. Water is often incorporated in the formation of crystals from aqueous solutions.[1] In some contexts, water of crystallization is the total mass of water in a substance at a given temperature and is mostly present in a definite (stoichiometric) ratio. Classically, "water of crystallization" refers to water that is found in the crystalline framework of a metal complex or a salt, which is not directly bonded to the metal cation.

Upon crystallization from water or moist solvents, many compounds incorporate water molecules in their crystalline frameworks. Water of crystallization can generally be removed by heating a sample but the crystalline properties are often lost. For example, in the case of sodium chloride, the dihydrate is unstable at room temperature.

2_connectivity.png)

Compared to inorganic salts, proteins crystallize with large amounts of water in the crystal lattice. A water content of 50% is not uncommon for proteins.

Nomenclature

In molecular formulas water of crystallization is indicated in various ways, but is often vague. The terms hydrated compound and hydrate are generally vaguely defined.

Position in the crystal structure

A salt with associated water of crystallization is known as a hydrate. The structure of hydrates can be quite elaborate, because of the existence of hydrogen bonds that define polymeric structures.[3] [4] Historically, the structures of many hydrates were unknown, and the dot in the formula of a hydrate was employed to specify the composition without indicating how the water is bound. Examples:

- CuSO4 • 5H2O - copper(II) sulfate pentahydrate

- CoCl2 • 6H2O - cobalt(II) chloride hexahydrate

- SnCl2 • 2H2O - tin(II) (or stannous) chloride dihydrate

For many salts, the exact bonding of the water is unimportant because the water molecules are labilized upon dissolution. For example, an aqueous solution prepared from CuSO4 • 5H2O and anhydrous CuSO4 behave identically. Therefore, knowledge of the degree of hydration is important only for determining the equivalent weight: one mole of CuSO4 • 5H2O weighs more than one mole of CuSO4. In some cases, the degree of hydration can be critical to the resulting chemical properties. For example, anhydrous RhCl3 is not soluble in water and is relatively useless in organometallic chemistry whereas RhCl3 • 3H2O is versatile. Similarly, hydrated AlCl3 is a poor Lewis acid and thus inactive as a catalyst for Friedel-Crafts reactions. Samples of AlCl3 must therefore be protected from atmospheric moisture to preclude the formation of hydrates.

6_improved_image.tif.png)

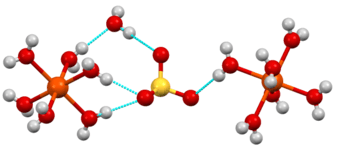

Crystals of hydrated copper(II) sulfate consist of [Cu(H2O)4]2+ centers linked to SO42− ions. Copper is surrounded by six oxygen atoms, provided by two different sulfate groups and four molecules of water. A fifth water resides elsewhere in the framework but does not bind directly to copper.[5] The cobalt chloride mentioned above occurs as [Co(H2O)6]2+ and Cl−. In tin chloride, each Sn(II) center is pyramidal (mean O/Cl-Sn-O/Cl angle is 83°) being bound to two chloride ions and one water. The second water in the formula unit is hydrogen-bonded to the chloride and to the coordinated water molecule. Water of crystallization is stabilized by electrostatic attractions, consequently hydrates are common for salts that contain +2 and +3 cations as well as −2 anions. In some cases, the majority of the weight of a compound arises from water. Glauber's salt, Na2SO4(H2O)10, is a white crystalline solid with greater than 50% water by weight.

Consider the case of nickel(II) chloride hexahydrate. This species has the formula NiCl2(H2O)6. Crystallographic analysis reveals that the solid consists of [trans-NiCl2(H2O)4] subunits that are hydrogen bonded to each other as well as two additional molecules of H2O. Thus 1/3 of the water molecules in the crystal are not directly bonded to Ni2+, and these might be termed "water of crystallization".

Analysis

The water content of most compounds can be determined with a knowledge of its formula. An unknown sample can be determined through thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) where the sample is heated strongly, and the accurate weight of a sample is plotted against the temperature. The amount of water driven off is then divided by the molar mass of water to obtain the number of molecules of water bound to the salt.

Other solvents of crystallization

Water is particularly common solvent to be found in crystals because it is small and polar. But all solvents can be found in some host crystals. Water is noteworthy because it is reactive, whereas other solvents such as benzene are considered to be chemically innocuous. Occasionally more than one solvent is found in a crystal, and often the stoichiometry is variable, reflected in the crystallographic concept of "partial occupancy." It is common and conventional for a chemist to "dry" a sample with a combination of vacuum and heat "to constant weight."

For other solvents of crystallization, analysis is conveniently accomplished by dissolving the sample in a deuterated solvent and analyzing the sample for solvent signals by NMR spectroscopy. Single crystal X-ray crystallography is often able to detect the presence of these solvents of crystallization as well. Other methods may be currently available.

Table of crystallization water in some inorganic halides

In the table below are indicated the number of molecules of water per metal in various salts.[6][7]

| Formula of hydrated metal halides | Coordination sphere of the metal | Equivalents of water of crystallization that are not bound to M | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| CaCl2(H2O)6 | [Ca(μ-H2O)6(H2O)3]2+ | none | Case of water as a bridging ligand[8] |

| VCl3(H2O)6 | trans-[VCl2(H2O)4]+ | two | |

| VBr3(H2O)6 | trans-[VBr2(H2O)4]+ | two | bromides and chlorides are usually similar |

| VI3(H2O)6 | [V(H2O)6]3+ | none | iodide competes poorly with water |

| CrCl3(H2O)6 | trans-[CrCl2(H2O)4]+ | two | dark green isomer, aka "Bjerrums's salt" |

| CrCl3(H2O)6 | [CrCl(H2O)5]2+ | one | blue-green isomer |

| CrCl2(H2O)4 | trans-[CrCl2(H2O)4] | none | square planar/tetragonal distortion |

| CrCl3(H2O)6 | [Cr(H2O)6]3+ | none | [9] |

| AlCl3(H2O)6 | [Al(H2O)6]3+ | none | isostructural with the Cr(III) compound |

| MnCl2(H2O)6 | trans-[MnCl2(H2O)4] | two | |

| MnCl2(H2O)4 | cis-[MnCl2(H2O)4] | none | cis molecular, the unstable trans isomer has also been detected[10] |

| MnBr2(H2O)4 | cis-[MnBr2(H2O)4] | none | cis, molecular |

| MnCl2(H2O)2 | trans-[MnCl4(H2O)2] | none | polymeric with bridging chloride |

| MnBr2(H2O)2 | trans-[MnBr4(H2O)2] | none | polymeric with bridging bromide |

| FeCl2(H2O)6 | trans-[FeCl2(H2O)4] | two | |

| FeCl2(H2O)4 | trans-[FeCl2(H2O)4] | none | molecular |

| FeBr2(H2O)4 | trans-[FeBr2(H2O)4] | none | molecular |

| FeCl2(H2O)2 | trans-[FeCl4(H2O)2] | none | polymeric with bridging chloride |

| FeCl3(H2O)6 | trans-[FeCl2(H2O)4]+ | two | one of four hydrates of ferric chloride,[11] isostructural with Cr analogue |

| FeCl3(H2O)2.5 | cis-[FeCl2(H2O)4]+ | two | the dihydrate has a similar structure, both contain FeCl4− anions.[11] |

| CoCl2(H2O)6 | trans-[CoCl2(H2O)4] | two | |

| CoBr2(H2O)6 | trans-[CoBr2(H2O)4] | two | |

| CoI2(H2O)6 | [Co(H2O)6]2+ | none[12] | iodide competes poorly with water |

| CoBr2(H2O)4 | trans-[CoBr2(H2O)4] | none | molecular |

| CoCl2(H2O)4 | cis-[CoCl2(H2O)4] | none | note: cis molecular |

| CoCl2(H2O)2 | trans-[CoCl4(H2O)2] | none | polymeric with bridging chloride |

| CoBr2(H2O)2 | trans-[CoBr4(H2O)2] | none | polymeric with bridging bromide |

| NiCl2(H2O)6 | trans-[NiCl2(H2O)4] | two | |

| NiCl2(H2O)4 | cis-[NiCl2(H2O)4] | none | note: cis molecular |

| NiBr2(H2O)6 | trans-[NiBr2(H2O)4] | two | |

| NiI2(H2O)6 | [Ni(H2O)6]2+ | none[12] | iodide competes poorly with water |

| NiCl2(H2O)2 | trans-[NiCl4(H2O)2] | none | polymeric with bridging chloride |

| CuCl2(H2O)2 | [CuCl4(H2O)2]2 | none | tetragonally distorted two long Cu-Cl distances |

| CuBr2(H2O)4 | [CuBr4(H2O)2]n | two | tetragonally distorted two long Cu-Br distances |

Hydrates of metal sulfates

Transition metal sulfates form a variety of hydrates, each of which crystallizes in only one form. The sulfate group often binds to the metal, especially for those salts with fewer than six aquo ligands. The heptahydrates, which are often the most common salts, crystallize as monoclinic and the less common orthorhombic forms. In the heptahydrates, one water is in the lattice and the other six are coordinated to the ferrous center.[13] Many of the metal sulfates occur in nature, being the result of weathering of mineral sulfides.[14]

| Formula of hydrated metal ion sulfate | Coordination sphere of the metal ion | Equivalents of water of crystallization that are not bound to M | mineral name | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MgSO4(H2O)6 | [Mg(H2O)6] | none | hexahydrite | common motif[14] |

| MgSO4(H2O)7 | [Mg(H2O)6] | one | epsomite | common motif[14] |

| TiOSO4(H2O) | [Ti(μ-O)2(H2O)(κ1-SO4)3] | none | further hydration gives gels | |

| VSO4(H2O)6 | [V(H2O)6] | none | Adopts the hexahydrite motif[15] | |

| VOSO4(H2O)5 | [VO(H2O)4(κ1-SO4)4] | one | ||

| Cr2(SO4)3(H2O)18 | [Cr(H2O)6] | six | One of several chromium(III) sulfates | |

| MnSO4(H2O) | [Mn(μ-H2O)2(κ1-SO4)4][16] | none | The most common of several hydrated manganese(II) sulfates | |

| FeSO4(H2O)7 | [Fe(H2O)6] | one | melanterite | see Mg analogue |

| CoSO4(H2O)7 | [Co(H2O)6] | one | see Mg analogue | |

| NiSO4(H2O)7 | [Ni(H2O)6] | one | morenosite | see Mg analogue |

| NiSO4(H2O)6 | [Ni(H2O)6] | none | retgersite | One of several nickel sulfate hydrates[17] |

| CuSO4(H2O)5 | [Cu(H2O)4(κ1-SO4)2] | one | chalcanthite | sulfate is bridging ligand[18] |

| CdSO4(H2O) | [Cd(μ-H2O)2(κ1-SO4)4] | none | bridging water ligand[19] | |

Gallery

Hydrated copper(II) sulfate is bright blue.

Hydrated copper(II) sulfate is bright blue. Anhydrous copper(II) sulfate is white.

Anhydrous copper(II) sulfate is white.

See also

References

- Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- Klewe, B.; Pedersen, B. (1974). "The crystal structure of sodium chloride dihydrate". Acta Crystallographica B. 30 (10): 2363–2371. doi:10.1107/S0567740874007138.

- Yonghui Wang et al. "Novel Hydrogen-Bonded Three-Dimensional Networks Encapsulating One-Dimensional Covalent Chains: ..." Inorg. Chem., 2002, 41 (24), pp. 6351–6357. doi:10.1021/ic025915o

- Carmen R. Maldonadoa, Miguel Quirós and J.M. Salas: "Formation of 2D water morphologies in the lattice of the salt..." Inorganic Chemistry Communications Volume 13, Issue 3, March 2010, p. 399–403; doi:10.1016/j.inoche.2009.12.033

- Moeller, Therald (Jan 1, 1980). Chemistry: With Inorganic qualitative Analysis. Academic Press Inc (London) Ltd. p. 909. ISBN 978-0-12-503350-3. Retrieved 15 June 2014.

- K. Waizumi, H. Masuda, H. Ohtaki, "X-ray structural studies of FeBr2 • 4H2O, CoBr2 • 4H2O, NiCl2 • 4H2O, and CuBr2 • 4H2O. cis/trans Selectivity in transition metal(I1) dihalide Tetrahydrate" Inorganica Chimica Acta, 1992 volume 192, pages 173–181.

- B. Morosin "An X-ray diffraction study on nickel(II) chloride dihydrate" Acta Crystallogr. 1967. volume 23, pp. 630-634. doi:10.1107/S0365110X67003305

- Agron, P.A.; Busing, W.R. "Calcium and strontium dichloride hexahydrates by neutron diffraction" Acta Crystallographica Section C 1986, volume 42, pp. 141-p1.

- violet isomer. isostructural with aluminium compound.Andress, K.R.; Carpenter, C. "Kristallhydrate. II.Die Struktur von Chromchlorid- und Aluminiumchloridhexahydrat" Zeitschrift für Kristallographie, Kristallgeometrie, Kristallphysik, Kristallchemie 1934, volume 87, p446-p463.

- Zalkin, Allan; Forrester, J. D.; Templeton, David H. (1964). "Crystal structure of manganese dichloride tetrahydrate". Inorganic Chemistry. 3 (4): 529–33. doi:10.1021/ic50014a017.

- Simon A. Cotton (2018). "Iron(III) chloride and its coordination chemistry". Journal of Coordination Chemistry. 71 (21): 3415–3443. doi:10.1080/00958972.2018.1519188.

- "Structure Cristalline et Expansion Thermique de L’Iodure de Nickel Hexahydrate" (Crystal structure and thermal expansion of nickel(II) iodide hexahydrate) Louër, Michele; Grandjean, Daniel; Weigel, Dominique Journal of Solid State Chemistry (1973), 7(2), 222-8. doi: 10.1016/0022-4596(73)90157-6

- Baur, W.H. "On the crystal chemistry of salt hydrates. III. The determination of the crystal structure of FeSO4(H2O)7 (melanterite)" Acta Crystallographica 1964, volume 17, p1167-p1174. doi:10.1107/S0365110X64003000

- Chou, I-Ming; Seal, Robert R.; Wang, Alian (2013). "The stability of sulfate and hydrated sulfate minerals near ambient conditions and their significance in environmental and planetary sciences". Journal of Asian Earth Sciences. 62: 734–758. Bibcode:2013JAESc..62..734C. doi:10.1016/j.jseaes.2012.11.027.

- Cotton, F. Albert; Falvello, Larry R.; Llusar, Rosa; Libby, Eduardo; Murillo, Carlos A.; Schwotzer, Willi (1986). "Synthesis and Characterization of Four Vanadium(II) Compounds, Including Vanadium(II) Sulfate Hexahydrate and Vanadium(II) Saccharinates". Inorganic Chemistry. 25 (19): 3423–3428. doi:10.1021/ic00239a021.

- Wildner, M.; Giester, G. (1991). "The Crystal Structures of Kieserite-type Compounds. I. Crystal Structures of Me(II)SO4*H2O (Me = Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Zn) (English translation)". Neues Jahrbuch fuer Mineralogie, Monatshefte: 296–p306.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Stadnicka, K.; Glazer, A.M.; Koralewski, M. "Structure, absolute configuration and optical activity of alpha-nickel sulfate hexahydrate" Acta Crystallographica, Section B: Structural Science (1987) 43, p319-p325.

- V. P. Ting, P. F. Henry, M. Schmidtmann, C. C. Wilson, M. T. Weller "In situ Neutron Powder Diffraction and Structure Determination in Controlled Humidities" Chem. Commun., 2009, 7527-7529. doi:10.1039/B918702B

- Theppitak, Chatphorn; Chainok, Kittipong (2015). "Crystal Structure of CdSO4(H2O): A Redetermination". Acta Crystallographica E. 71: i8-i9. doi:10.1107/S2056989015016904.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)