Galwan River

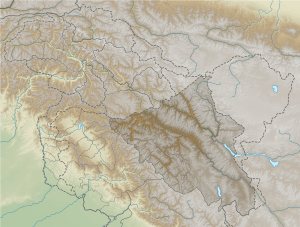

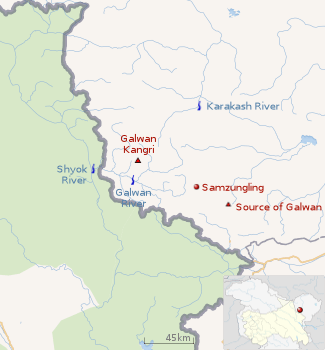

The Galwan River flows from the disputed Aksai Chin region administered by China to the Ladakh union territory of India. It originates to the east of the area of Samzungling on the eastern side of the Karakoram range and flows west to join the Shyok River at 34°45′33″N 78°10′13″E. It is one of the upstream tributaries of the Indus River.

| Galwan River | |

|---|---|

Mouth of the Galwan River in Ladakh to the west of the Sino-Indian Line of Actual Control | |

| Location | |

| Countries | China and India |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | |

| • location | Aksai Chin/Ladakh |

| • coordinates | 34.588°N 78.912°E |

| Mouth | |

• location | Shyok River |

• coordinates | 34°45′33″N 78°10′13″E |

| Basin features | |

| River system | Indus River |

| Galwan River | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 加勒萬河 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 加勒万河 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Hindi name | |||||||

| Hindi | गलवान नदी | ||||||

Etymology

The river is named after Ghulam Rasool Galwan, a Ladakhi explorer of Kashmiri descent, who first explored the course of the river. In 1899, he was part of a British expedition team that was exploring the areas to the north of the Chang Chenmo valley, when he ran into this previously unknown river valley. Harish Kapadia states that this is one of the rare instances where a major geographical feature is named after a native explorer.[1][2][3]

Course

|

|

The river's length is about 100 kilometres, and it is fast-flowing.

Sino-Indian border dispute

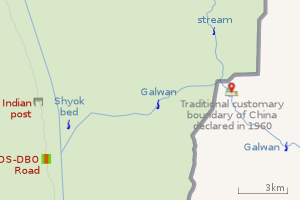

The Galwan river is to the west of China's 1956 claim line in Aksai Chin. However, in 1960 China advanced its claim line to the west of the river along the mountain ridge adjoining the Shyok river valley.[5] Meanwhile, India continued to claim the entire Aksai Chin plateau.

1962 standoff

These claims and counterclaims led to a military standoff in the Galwan River valley in 1962. On 4 July, a platoon of Indian Gorkha troops set up a post in the upper reaches of the valley. The post ended up cutting the lines of communication to a Chinese post at Samzungling. The Chinese interpreted it as a premeditated attack on their post, and surrounded the Indian post, coming within 100 yards of the post. The Indian government warned China of "grave consequences" and informed them that India was determined to hold the post at all costs. The post remained surrounded for four months and was supplied by helicopters. According to scholar Taylor Fravel, the standoff marked the "apogee of tension" for China's leaders.[6][7][8][9]

1962 war

By the time the Sino-Indian War started on 20 October 1962, the Indian post had been reinforced by a company of troops. The Chinese PLA bombarded the Indian post with heavy shelling and employed a battalion to attack it. The Indian garrison suffered 33 killed and several wounded, while the company commander and several others were taken prisoner.[6][7] By the end of the war, China reached its 1960 claim line.[5]

2020 standoff

In summer 2020, India and China have been engaged in a military stand-off at multiple locations along the Sino-Indian border. On 16 June 2020, it was reported that a violent clash took place between troops of the two countries near India's Patrolling Point 14 in Galwan Valley. Twenty Indian Army soldiers and an unknown number of Chinese soldiers were killed.[10]

References

- Kapadia, Harish (2005), Into the Untravelled Himalaya: Travels, Treks, and Climbs, Indus Publishing, pp. 215–216, ISBN 978-81-7387-181-8

- Kapadia, Harish (1992), "Lots in a Name", The Himalayan Journal, 48

- Backstory of Ladakh’s Galwan Valley and the legend of Rassul Galwan, Kashmir Observer, 31 May 2020.

-

India, Ministry of External Affairs, ed. (1962), Report of the Officials of the Governments of India and the People's Republic of China on the Boundary Question, Government of India Press, Chinese Report, Part 1, pp. 4–5

The location and terrain features of this traditional customary boundary line are now described as follows in three sectors, western, middle and eastern. ... [From the Chip Chap river] It then turns south-east along the mountain ridge and passes through peak 6,845 (approximately 78° 12' E, 34° 57' N) and peak 6,598 (approximately 78° 13' E, 34° 54' N). From peak 6,598 it runs along the mountain ridge southwards until it crosses the Galwan River at approximately 78° 13' E, 34° 46' N. - Hoffmann, Steven A. (1990), India and the China Crisis, University of California Press, pp. 76, 93, ISBN 978-0-520-06537-6

- Raghavan, Srinath (2010), War and Peace in Modern India, Palgrave Macmillan, p. 287, ISBN 978-1-137-00737-7

- Cheema, Brig Amar (2015), The Crimson Chinar: The Kashmir Conflict: A Politico Military Perspective, Lancer Publishers, p. 186, ISBN 978-81-7062-301-4

- Fravel, M. Taylor (2008), Strong Borders, Secure Nation: Cooperation and Conflict in China's Territorial Disputes, Princeton University Press, p. 186, ISBN 1-4008-2887-2

- Pranab Dhal Samanta, Galwan River Valley: An important history lesson, The Economic Times, 29 June 2020.

- Editor Of Beijing Mouthpiece Global Times Acknowledges Casualties For China, NDTV, 16 June 2020.

Further reading

- Kler, Gurdip Singh (1995), Unsung Battles of 1962, Lancer Publishers, pp. 111–, ISBN 978-1-897829-09-7

- Galwan, Ghulam Rassul (1923), Servant Of Sahibs, Cambridge, ISBN 81-206-1957-9

External links