Bookbinding

Bookbinding is the process of physically assembling a book of codex format from an ordered stack of paper sheets that are folded together into sections or sometimes left as a stack of individual sheets. The stack is then bound together along one edge by either sewing with thread through the folds or by a layer of flexible adhesive. Alternative methods of binding that are cheaper but less permanent include loose-leaf rings, individual screw posts or binding posts, twin loop spine coils, plastic spiral coils, and plastic spine combs. For protection, the bound stack is either wrapped in a flexible cover or attached to stiff boards. Finally, an attractive cover is adhered to the boards, including identifying information and decoration. Book artists or specialists in book decoration can also greatly enhance a book's content by creating book-like objects with artistic merit of exceptional quality.

.jpg)

Before the computer age, the bookbinding trade involved two divisions. First, there was stationery binding (known as vellum binding in the trade) that deals with books intended for handwritten entries such as accounting ledgers, business journals, blank books, and guest log books, along with other general office stationery such as note books, manifold books, day books, diaries, portfolios, etc. Computers have now replaced the pen and paper based accounting that constituted most of the stationery binding industry. Second was letterpress binding which deals with making books intended for reading, including library binding, fine binding, edition binding, and publisher's bindings.[1] A third division deals with the repair, restoration, and conservation of old used bindings.

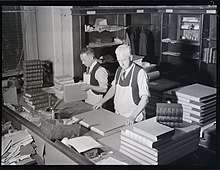

Today, modern bookbinding is divided between hand binding by individual craftsmen working in a shop and commercial bindings mass-produced by high-speed machines in a factory. There is a broad grey area between the two divisions. The size and complexity of a bindery shop varies with job types, for example, from one-of-a-kind custom jobs, to repair/restoration work, to library rebinding, to preservation binding, to small edition binding, to extra binding, and finally to large-run publisher's binding. There are cases where the printing and binding jobs are combined in one shop. For the largest numbers of copies, commercial binding is effected by production runs of ten thousand copies or more in a factory.

Overview

Bookbinding is a specialized trade that relies on basic operations of measuring, cutting, and gluing. A finished book might need dozens of operations to complete, according to the specific style and materials. Bookbinding combines skills from other trades such as paper and fabric crafts, leather work, model making, and graphic arts. It requires knowledge about numerous varieties of book structures along with all the internal and external details of assembly. A working knowledge of the materials involved is required. A book craftsman needs a minimum set of hand tools but with experience will find an extensive collection of secondary hand tools and even items of heavy equipment that are valuable for greater speed, accuracy, and efficiency.

Bookbinding is an artistic craft of great antiquity, and at the same time, a highly mechanized industry. The division between craft and industry is not so wide as might at first be imagined. It is interesting to observe that the main problems faced by the mass-production bookbinder are the same as those that confronted the medieval craftsman or the modern hand binder. The first problem is still how to hold together the pages of a book; secondly is how to cover and protect the gathering of pages once they are held together; and thirdly, how to label and decorate the protective cover.[2]

History

Origins of the book

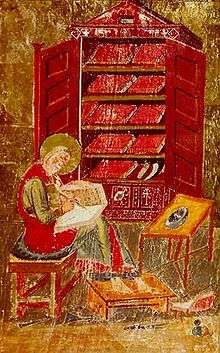

Writers in the Hellenistic-Roman culture wrote longer texts as scrolls; these were stored in boxes or shelving with small cubbyholes, similar to a modern winerack. Court records and notes were written on wax tablets, while important documents were written on papyrus or parchment. The modern English word book comes from the Proto-Germanic *bokiz, referring to the beechwood on which early written works were recorded.[3]

The book was not needed in ancient times, as many early Greek texts—scrolls—were 30 pages long, which were customarily folded accordion-fashion to fit into the hand. Roman works were often longer, running to hundreds of pages. The Greeks used to call their books tome, meaning "to cut". The Egyptian Book of the Dead was a massive 200 pages long and was used in funerary services for the deceased. Torah scrolls, editions of the Jewish holy book, were—and still are—also held in special holders when read.

Scrolls can be rolled in one of two ways. The first method is to wrap the scroll around a single core, similar to a modern roll of paper towels. While simple to construct, a single core scroll has a major disadvantage: in order to read text at the end of the scroll, the entire scroll must be unwound. This is partially overcome in the second method, which is to wrap the scroll around two cores, as in a Torah. With a double scroll, the text can be accessed from both beginning and end, and the portions of the scroll not being read can remain wound. This still leaves the scroll a sequential-access medium: to reach a given page, one generally has to unroll and re-roll many other pages.

Early book formats

In addition to the scroll, wax tablets were commonly used in Antiquity as a writing surface. Diptychs and later polyptych formats were often hinged together along one edge, analogous to the spine of modern books, as well as a folding concertina format. Such a set of simple wooden boards sewn together was called by the Romans a codex (pl. codices)—from the Latin word caudex, meaning "the trunk" of a tree, around the first century AD. Two ancient polyptychs, a pentaptych and octoptych, excavated at Herculaneum employed a unique connecting system that presages later sewing on thongs or cords.[4]

At the turn of the first century, a kind of folded parchment notebook called pugillares membranei in Latin, became commonly used for writing throughout the Roman Empire.[5] This term was used by both the pagan Roman poet Martial and Christian apostle Paul the Apostle. Martial used the term with reference to gifts of literature exchanged by Romans during the festival of Saturnalia. According to T. C. Skeat, "in at least three cases and probably in all, in the form of codices" and he theorized that this form of notebook was invented in Rome and then "must have spread rapidly to the Near East".[6] In his discussion of one of the earliest pagan parchment codices to survive from Oxyrhynchus in Egypt, Eric Turner seems to challenge Skeat's notion when stating "its mere existence is evidence that this book form had a prehistory" and that "early experiments with this book form may well have taken place outside of Egypt".[7]

Early intact codices were discovered at Nag Hammadi in Egypt. Consisting of primarily Gnostic texts in Coptic, the books were mostly written on papyrus, and while many are single-quire, a few are multi-quire. Codices were a significant improvement over papyrus or vellum scrolls in that they were easier to handle. However, despite allowing writing on both sides of the leaves, they were still foliated—numbered on the leaves, like the Indian books. The idea spread quickly through the early churches, and the word Bible comes from the town where the Byzantine monks established their first scriptorium, Byblos, in modern Lebanon. The idea of numbering each side of the page—Latin pagina, "to fasten"—appeared when the text of the individual testaments of the Bible were combined and text had to be searched through more quickly. This book format became the preferred way of preserving manuscript or printed material.

Development

The codex-style book, using sheets of either papyrus or vellum (before the spread of Chinese papermaking outside of Imperial China), was invented in the Roman Empire during the 1st century AD.[8] First described by the poet Martial from Roman Spain, it largely replaced earlier writing mediums such as wax tablets and scrolls by the year 300 AD.[9] By the 6th century AD, the scroll and wax tablet had been completely replaced by the codex in the Western world.[10]

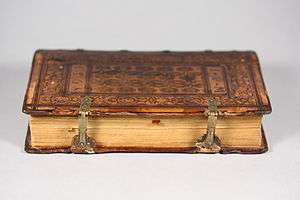

Western books from the fifth century onwards were bound between hard covers, with pages made from parchment folded and sewn onto strong cords or ligaments that were attached to wooden boards and covered with leather. Since early books were exclusively handwritten on handmade materials, sizes and styles varied considerably, and there was no standard of uniformity. Early and medieval codices were bound with flat spines, and it was not until the fifteenth century that books began to have the rounded spines associated with hardcovers today.[11] Because the vellum of early books would react to humidity by swelling, causing the book to take on a characteristic wedge shape, the wooden covers of medieval books were often secured with straps or clasps. These straps, along with metal bosses on the book's covers to keep it raised off the surface that it rests on, are collectively known as furniture.[12]

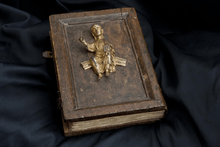

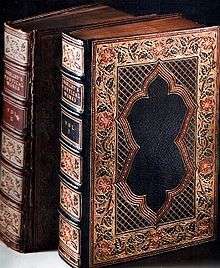

The earliest surviving European bookbinding is the St Cuthbert Gospel of about 700, in red goatskin, now in the British Library, whose decoration includes raised patterns and coloured tooled designs. Very grand manuscripts for liturgical rather than library use had covers in metalwork called treasure bindings, often studded with gems and incorporating ivory relief panels or enamel elements. Very few of these have survived intact, as they have been broken up for their precious materials, but a fair number of the ivory panels have survived, as they were hard to recycle; the divided panels from the Codex Aureus of Lorsch are among the most notable. The 8th century Vienna Coronation Gospels were given a new gold relief cover in about 1500, and the Lindau Gospels (now Morgan Library, New York) have their original cover from around 800.[13]

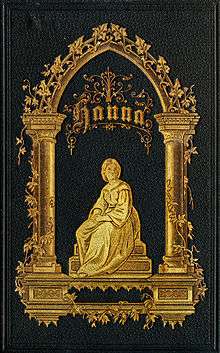

Luxury medieval books for the library had leather covers decorated, often all over, with tooling (incised lines or patterns), blind stamps, and often small metal pieces of furniture. Medieval stamps showed animals and figures as well as the vegetal and geometric designs that would later dominate book cover decoration. Until the end of the period books were not usually stood up on shelves in the modern way. The most functional books were bound in plain white vellum over boards, and had a brief title hand-written on the spine. Techniques for fixing gold leaf under the tooling and stamps were imported from the Islamic world in the 15th century, and thereafter the gold-tooled leather binding has remained the conventional choice for high quality bindings for collectors, though cheaper bindings that only used gold for the title on the spine, or not at all, were always more common. Although the arrival of the printed book vastly increased the number of books produced in Europe, it did not in itself change the various styles of binding used, except that vellum became much less used.[14]

Introduction of paper

Although early, coarse hempen paper had existed in China during the Western Han period (202 BC - 9 AD), the Eastern-Han Chinese court eunuch Cai Lun (ca. 50 AD – 121 AD) introduced the first significant improvement and standardization of papermaking by adding essential new materials into its composition.[15]

Bookbinding in medieval China replaced traditional Chinese writing supports such as bamboo and wooden slips, as well as silk and paper scrolls.[16] The evolution of the codex in China began with folded-leaf pamphlets in the 9th century AD, during the late Tang Dynasty (618-907 AD), improved by the 'butterfly' bindings of the Song dynasty (960-1279 AD), the wrapped back binding of the Yuan dynasty (1271-1368), the stitched binding of the Ming (1368-1644 AD) and Qing dynasties (1644-1912), and finally the adoption of Western-style bookbinding in the 20th century (coupled with the European printing press that replaced traditional Chinese printing methods).[17] The initial phase of this evolution, the accordion-folded palm-leaf-style book, most likely came from India and was introduced to China via Buddhist missionaries and scriptures.[18]

With the arrival (from the East) of rag paper manufacturing in Europe in the late Middle Ages and the use of the printing press beginning in the mid-15th century, bookbinding began to standardize somewhat, but page sizes still varied considerably.. Paper leaves also meant that heavy wooden boards and metal furniture were no longer necessary to keep books closed, allowing for much lighter pasteboard covers. The practice of rounding and backing the spines of books to create a solid, smooth surface and "shoulders" supporting the textblock against its covers facilitated the upright storage of books and titling on spine. This became common practice by the close of the 16th century but was consistently practiced in Rome as early as the 1520s.[19][20]

In the early sixteenth century, the Italian printer Aldus Manutius realized that personal books would need to fit in saddle bags and thus produced books in the smaller formats of quartos (one-quarter-size pages) and octavos (one-eighth-size pages).[21]

Leipzig, a prominent centre of the German book-trade, in 1739 had 20 bookshops, 15 printing establishments, 22 book-binders and three type-foundries in a population of 28,000 people.[22]

In the German book-distribution system of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the end-user buyers of books "generally made separate arrangements with either the publisher or a bookbinder to have printed sheets bound according to their wishes and their budget".[23]

The reduced cost of books facilitated cheap lightweight Bibles, made from tissue-thin oxford paper, with floppy covers, that resembled the early Arabic Qurans, enabling missionaries to take portable books with them around the world, and modern wood glues enabled the addition of paperback covers to simple glue bindings.

Historical forms of binding

Historical forms of binding include the following:[24]

- Coptic binding: a method of sewing leaves/pages together

- Ethiopian binding

- Long-stitch bookbinding

- Islamic bookcover with a distinctive flap on the back cover that wraps around to the front when the book is closed.[25]

- Wooden-board binding

- Limp vellum binding

- Calf binding ("leather-bound")

- Paper case binding

- In-board cloth binding

- Cased cloth binding

- Embroidered binding[26]

- Bradel binding

- Traditional Chinese and Korean bookbinding and Japanese stab binding

- Girdle binding

- Anthropodermic bibliopegy (rare) bookbinding in human skin.

- Secret Belgian binding (or "criss-cross binding"), invented in 1986, was erroneously identified as a historical method.[27]

Some older presses could not separate the pages of a book, so readers used a paper knife to separate the outer edges of pages as a book was read.

Modern commercial binding

There are various commercial techniques in use today. Today, most commercially produced books belong to one of four categories:

Hardcover binding

A hardcover, hardbound or hardback book has rigid covers and is stitched in the spine. Looking from the top of the spine, the book can be seen to consist of a number of signatures bound together. When the book is opened in the middle of a signature, the binding threads are visible. Signatures of hardcover books are typically octavo (a single sheet folded three times), though they may also be folio, quarto, or 16mo (see Book size). Unusually large and heavy books are sometimes bound with wire.

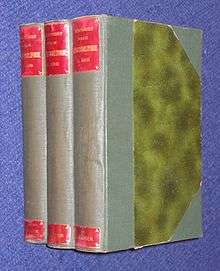

Until the mid-20th century, covers of mass-produced books were laid with cloth, but from that period onward, most publishers adopted clothette, a kind of textured paper which vaguely resembles cloth but is easily differentiated on close inspection. Most cloth-bound books are now half-and-half covers with cloth covering only the spine. In that case, the cover has a paper overlap. The covers of modern hardback books are made of thick cardboard.

Some books that appeared in the mid-20th century signature-bound appear in reprinted editions in glued-together editions. Copies of such books stitched together in their original format are often difficult to find, and are much sought after for both aesthetic and practical reasons.

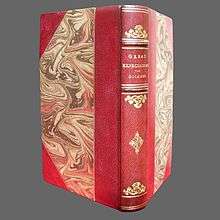

A variation of the hardcover which is more durable is the calf-binding, where the cover is either half or fully clad in leather, usually from a calf. This is also called full-bound or, simply, leather bound.

Library binding refers to the hardcover binding of books intended for the rigors of library use and are largely serials and paperback publications. Though many publishers have started to provide "library binding" editions, many libraries elect to purchase paperbacks and have them rebound in hard covers for longer life.

Methods of hardcover binding

There are a number of methods used to bind hardcover books. Those still in use include:

- Case binding is the most common type of hardcover binding for books. The pages are arranged in signatures and glued together into a "textblock." The textblock is then attached to the cover or "case" which is made of cardboard covered with paper, cloth, vinyl or leather. This is also known as cloth binding, or edition binding.

- Oversewing, where the signatures of the book start off as loose pages which are then clamped together. Small vertical holes are punched through the far left-hand edge of each signature, and then the signatures are sewn together with lock-stitches to form the text block. Oversewing is a very strong method of binding and can be done on books up to five inches thick. However, the margins of oversewn books are reduced and the pages will not lie flat when opened.

- Sewing through the fold (also called Smyth Sewing), where the signatures of the book are folded and stitched through the fold. The signatures are then sewn and glued together at the spine to form a text block. In contrast to oversewing, through-the-fold books have wide margins and can open completely flat. Many varieties of sewing stitches exist, from basic links to the often used Kettle Stitch. While Western books are generally sewn through punched holes or sawed notches along the fold, some Asian bindings, such as the Retchoso or Butterfly Stitch of Japan, use small slits instead of punched holes.

- Double-fan adhesive binding starts off with two signatures of loose pages, which are run over a roller—"fanning" the pages—to apply a thin layer of glue to each page edge. Then the two signatures are perfectly aligned to form a text block, and glue edges of the text block are attached to a piece of cloth lining to form the spine. Double-fan adhesive bound books can open completely flat and have a wide margin. However, certain types of paper do not hold adhesive well, and, with wear and tear, the pages can come loose.[28]

Punch and bind

Different types of the punch and bind binding include:

- Double wire, twin loop, or Wire-O binding is a type of binding that is used for books that will be viewed or read in an office or home type environment. The binding involves the use of a "C" shaped wire spine that is squeezed into a round shape using a wire closing device. Double wire binding allows books to have smooth crossover and is affordable in many colors. This binding is great for annual reports, owners manuals and software manuals. Wire bound books are made of individual sheets, each punched with a line of round or square holes on the binding edge. This type of binding uses either a 3:1 pitch hole pattern with three holes per inch or a 2:1 pitch hole pattern with two holes per inch. The three to one hole pattern is used for smaller books that are up to 9/16" in diameter while the 2:1 pattern is normally used for thicker books as the holes are slightly bigger to accommodate slightly thicker, stronger wire. Once punched, the back cover is then placed on to the front cover ready for the wire binding elements (double loop wire) to be inserted. The wire is then placed through the holes. The next step involves the binder holding the book by its pages and inserting the wire into a "closer" which is basically a vise that crimps the wire closed and into its round shape. The back page can then be turned back to its correct position, thus hiding the spine of the book.

- Comb binding uses a 9/16" pitch rectangular hole pattern punched near the bound edge. A curled plastic "comb" is fed through the slits to hold the sheets together. Comb binding allows a book to be disassembled and reassembled by hand without damage. Comb supplies are typically available in a wide range of colors and diameters. The supplies themselves can be re-used or recycled. In the United States, comb binding is often referred to as 19-ring binding because it uses a total of 19 holes along the 11-inch side of a sheet of paper.

- VeloBind is used to permanently rivet pages together using a plastic strip on the front and back of the document. Sheets for the document are punched with a line of holes near the bound edge. A series of pins attached to a plastic strip called a Comb feeds through the holes to the other side and then goes through another plastic strip called the receiving strip. The excess portion of the pins is cut off and the plastic heat-sealed to create a relatively flat bind method. VeloBind provides a more permanent bind than comb-binding, but is primarily used for business and legal presentations and small publications.

- Spiral binding is the most economical form of mechanical binding when using plastic or metal. It is commonly used for atlases and other publications where it is necessary or desirable to be able to open the publication back on itself without breaking the spine. There are several types but basically it is made by punching holes along the entire length of the spine of the page and winding a wire helix (like a spring) through the holes to provide a fully flexible hinge at the spine. Spiral coil binding uses a number of different hole patterns for binding documents. The most common hole pattern used with this style is 4:1 pitch (4 holes per inch). However, spiral coil spines are also available for use with 3:1 pitch, 5:1 pitch and 0.400-hole patterns.

Thermally activated binding

Some of the different types of thermally activated binding include:

- Perfect binding is often used for paperback books. It is also used for magazines; National Geographic is one example of this type. Perfect-bound books usually consist of various sections with a cover made from heavier paper, glued together at the spine with a strong glue. The sections are milled in the back and notches are applied into the spine to allow hot glue to penetrate into the spine of the book. The other three sides are then face-trimmed. This is what allows the magazine or paperback book to be opened. Mass-market paperbacks (pulp paperbacks) are small (16mo size), cheaply made with each sheet fully cut and glued at the spine; these are likely to fall apart or lose sheets after much handling or several years. Trade paperbacks are more sturdily made, with traditional gatherings or sections of bifolios, usually larger, and more expensive. The difference between the two can usually easily be seen by looking for the sections in the top or bottom sides of the book.

- Thermal binding uses a one-piece cover with glue down the spine to quickly and easily bind documents without the need for punching. Individuals usually purchase "thermal covers" or "therm-a-bind covers", which are usually made to fit a standard-size sheet of paper and come with a glue channel down the spine. The paper is placed in the cover, heated in a machine (basically a griddle), and when the glue cools, it adheres the paper to the spine. Thermal glue strips can also be purchased separately for individuals that wish to use customized/original covers. However, creating documents using thermal binding glue strips can be a tedious process, which requires a scoring device and a large-format printer.

- A cardboard article looks like a hardbound book at first sight, but it is really a paperback with hard covers. Many books that are sold as hardcover are actually of this type. The Modern Library series is an example. This type of document is usually bound with thermal adhesive glue using a perfect-binding machine.

- Tape binding refers to a system that wraps and glues a piece of tape around the base of the document. A tape-binding machine such as the PLANAX COPY Binder or Powis Parker Fastback system will usually be used to complete the binding process and to activate the thermal adhesive on the glue strip. However, some users also refer to tape binding as the process of adding a colored tape to the edge of a mechanically fastened (stapled or stitched) document.

Stitched or sewn binding

Types of stitched or sewn bindings:

- A sewn book is constructed in the same way as a hardbound book, except that it lacks the hard covers. The binding is as durable as that of a hardbound book.

- Stapling through the centerfold, also called saddle-stitching, joins a set of nested folios into a single magazine issue; most comic books are well-known examples of this type.

- Magazines are considered more ephemeral than books, and less durable means of binding them are usual. In general, the cover papers of magazines will be the same as the inner pages (self-cover)[29] or only slightly heavier (plus cover). Most magazines are stapled or saddle-stitched; however, some are bound with perfect binding and use thermally activated adhesive.

Modern hand binding

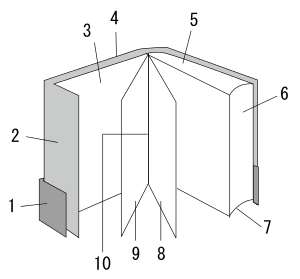

- Belly band

- Flap

- Endpaper

- Book cover

- Head

- Foredge

- Tail

- Right page, recto

- Left page, verso

- Gutter

Modern bookbinding by hand can be seen as two closely allied fields: the creation of new bindings, and the repair of existing bindings. Bookbinders are often active in both fields. Bookbinders can learn the craft through apprenticeship; by attending specialized trade schools;[30] by taking classes in the course of university studies, or by a combination of those methods. Some European countries offer a Master Bookbinder certification, though no such certification exists in the United States. MFA programs that specialize in the 'Book Arts' (hand paper-making, printmaking and bookbinding) are available through certain colleges and universities.[31]

Hand bookbinders create new bindings that run the gamut from historical book structures made with traditional materials to modern structures made with 21st-century materials, and from basic cloth-case bindings to valuable full-leather fine bindings. Repairs to existing books also encompass a broad range of techniques, from minimally invasive conservation of a historic book to the full restoration and rebinding of a text.

Though almost any existing book can be repaired to some extent, only books that were originally sewn can be rebound by resewing. Repairs or restorations are often done to emulate the style of the original binding. For new works, some publishers print unbound manuscripts which a binder can collate and bind, but often an existing commercially bound book is pulled, or taken apart, in order to be given a new binding. Once the textblock of the book has been pulled, it can be rebound in almost any structure; a modern suspense novel, for instance, could be rebound to look like a 16th-century manuscript. Bookbinders may bind several copies of the same text, giving each copy a unique appearance.

Hand bookbinders use a variety of specialized hand tools, the most emblematic of which is the bonefolder, a flat, tapered, polished piece of bone used to crease paper and apply pressure.[32] Additional tools common to hand bookbinding include a variety of knives and hammers, as well as brass tools used during finishing.

When creating new work, modern hand binders often work on commission, creating bindings for specific books or collections. Books can be bound in many different materials. Some of the more common materials for covers are leather, decorative paper, and cloth (see also: buckram). Those bindings that are made with exceptionally high craftsmanship, and that are made of particularly high-quality materials (especially full leather bindings), are known as fine or extra bindings. Also, when creating a new work, modern binders may wish to select a book that has already been printed and create what is known as a 'design binding'. "In a typical design binding, the binder selects an already printed book, disassembles it, and rebinds it in a style of fine binding—rounded and backed spine, laced-in boards, sewn headbands, decorative end sheets, leather cover etc."[33]

Conservation and restoration

Conservation and restoration are practices intended to repair damage to an existing book. While they share methods, their goals differ. The goal of conservation is to slow the book's decay and restore it to a usable state while altering its physical properties as little as possible. Conservation methods have been developed in the course of taking care of large collections of books. The term archival comes from taking care of the institutions archive of books. The goal of restoration is to return the book to a previous state as envisioned by the restorer, often imagined as the original state of the book. The methods of restoration have been developed by bookbinders with private clients mostly interested in improving their collections.

In either case, one of the modern standard for conservation and restoration is "reversibility". That is, any repair should be done in such a way that it can be undone if and when a better technique is developed in the future. Bookbinders echo the physician's creed, "First, do no harm". While reversibility is one standard, longevity of the functioning of the book is also very important and sometimes takes precedence over reversibility especially in areas that are invisible to the reader such as the spine lining.

Books requiring restoration or conservation treatment run the gamut from the very earliest of texts to books with modern bindings that have undergone heavy usage. For each book, a course of treatment must be chosen that takes into account the book's value, whether it comes from the binding, the text, the provenance, or some combination of the three. Many people choose to rebind books, from amateurs who restore old paperbacks on internet instructions to many professional book and paper conservators and restorationists, who often in the United States are members of the American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works (AIC).

Many times, books that need to be restored are hundreds of years old, and the handling of the pages and binding has to be undertaken with great care and a delicate hand. The archival process of restoration and conservation can extend a book's life for many decades and is necessary to preserve books that sometimes are limited to a small handful of remaining copies worldwide.

Typically, the first step in saving and preserving a book is its deconstruction. The text pages need to be separated from the covers and, only if necessary, the stitching removed. This is done as delicately as possible. All page restoration is done at this point, be it the removal of foxing, ink stains, page tears, etc. Various techniques are employed to repair the various types of page damage that might have occurred during the life of the book.

The preparation of the "foundations" of the book could mean the difference between a beautiful work of art and a useless stack of paper and leather.

The sections are then hand-sewn in the style of its period, back into book form, or the original sewing is strengthened with new lining on the text-spine. New hinges must be accounted for in either case both with text-spine lining and some sort of end-sheet restoration.

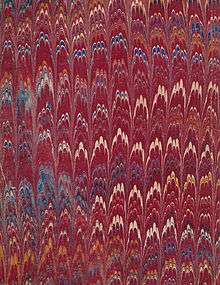

The next step is the restoration of the book cover; This can be as complicated as completely re-creating a period binding to match the original using whatever is appropriate for that time it was originally created. Sometimes this means a new full leather binding with vegetable tanned leather, dyed with natural dyes, and hand-marbled papers may be used for the sides or end-sheets. Finally the cover is hand-tooled in gold leaf. The design of the book cover involves such hand-tooling, where an extremely thin layer of gold is applied to the cover. Such designs can be lettering, symbols, or floral designs, depending on the nature of any particular project.

Sometimes the restoration of the cover is a matter of surgically strengthening the original cover by lifting the original materials and applying new materials for strength. This is perhaps a more common method for covers made with book-cloth although leather books can be approached this way as well. Materials such as Japanese tissues of various weights may be used. Colors may be matched using acrylic paints or simple colored pencils.

It is harder to restore leather books typically because of the fragility of the materials.

Terms and techniques

Most of the following terms apply only with respect to American practices:

- A leaf (often wrongly referred to as a folio) typically has two pages of text and/or images, front and back, in a finished book. The Latin for leaf is folium, therefore the ablative "folio" ("on the folium") should be followed by a designation to distinguish between recto and verso. Thus "folio 5r" means "on the recto of the leaf numbered 5". Although technically not accurate, common usage is "on folio 5r". In everyday speech it is common to refer to "turning the pages of a book", although it would be more accurate to say "turning the leaves of a book"; this is the origin of the phrase "to turn over a new leaf" i.e. to start on a fresh blank page.

- The recto side of a leaf faces left when the leaf is held straight up from the spine (in a paginated book this is usually an odd-numbered page).

- The verso side of a leaf faces right when the leaf is held straight up from the spine (in a paginated book this is usually an even-numbered page).

- A bifolium (often wrongly called a "bifolio", "bi-folio", or even "bifold") is a single sheet folded in half to make two leaves. The plural is "bifolia", not "bifolios".

- A section, sometimes called a gathering, or, especially if unprinted, a quire,[34] is a group of bifolia nested together as a single unit.[35] In a completed book, each quire is sewn through its fold. Depending of how many bifolia a quire is made of, it could be called:[36]

- duernion – two bifolia, producing four leaves;

- ternion – three bifolia, producing six leaves;

- quaternion – four bifolia, producing eight leaves;

- quinternion – five bifolia, producing ten leaves;

- sextern or sexternion[37] – six bifolia, producing twelve leaves.

- A codex is a series of one or more quires sewn through their folds, and linked together by the sewing thread.

- A signature, in the context of printed books, is a section that contains text. Though the term signature technically refers to the signature mark, traditionally a letter or number printed on the first leaf of a section in order to facilitate collation, the distinction is rarely made today.[38]

- Folio, quarto, and so on may also refer to the size of the finished book, based on the size of sheet that an early paper maker could conveniently turn out with a manual press. Paper sizes could vary considerably, and the finished size was also affected by how the pages were trimmed, so the sizes given are rough values only.

- A folio volume is typically 15 in (38 cm) or more in height, the largest sort of regular book.

- A quarto volume is typically about 9 by 12 in (23 by 30 cm), roughly the size of most modern magazines. A sheet folded in quarto (also 4to or 4º) is folded in half twice at right angles to make four leaves. Also called: eight-page signature.

- An octavo volume is typically about 5 to 6 in (13 to 15 cm) by 8 to 9 in (20 to 23 cm), the size of most modern digest magazines or trade paperbacks. A sheet folded in octavo (also 8vo or 8º) is folded in half 3 times to make 8 leaves. Also called: sixteen-page signature.

- A sextodecimo volume is about 4 1⁄2 by 6 3⁄4 in (11 by 17 cm), the size of most mass market paperbacks. A sheet folded in sextodecimo (also 16mo or 16º) is folded in half 4 times to make 16 leaves. Also called: 32-page signature.

- Duodecimo or 12mo, 24mo, 32mo, and even 64mo are other possible sizes. Modern paper mills can produce very large sheets, so a modern printer will often print 64 or 128 pages on a single sheet.

- Trimming separates the leaves of the bound book. A sheet folded in quarto will have folds at the spine and also across the top, so the top folds must be trimmed away before the leaves can be turned. A quire folded in octavo or greater may also require that the other two sides be trimmed. Deckle edge, or Uncut books are untrimmed or incompletely trimmed, and may be of special interest to book collectors.

Paperback binding

Though books are sold as hardcover or paperback, the actual binding of the pages is important to durability. Most paperbacks and some hard cover books have a "perfect binding". The pages are aligned or cut together and glued. A strong and flexible layer, which may or may not be the glue itself, holds the book together. In the case of a paperback, the visible portion of the spine is part of this flexible layer.

Spine

Orientation

In languages written from left to right, such as English, books are bound on the left side of the cover; looking from on top, the pages increase counter-clockwise. In right-to-left languages, books are bound on the right. In both cases, this is so the end of a page coincides with where it is turned. Many translations of Japanese comic books retain the binding on the right, which allows the art, laid out to be read right-to-left, to be published without mirror-imaging it.

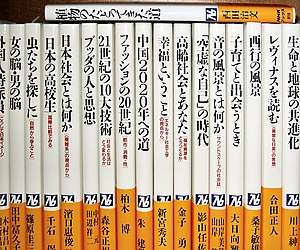

In China (only areas using Traditional Chinese), Japan, and Taiwan, literary books are written top-to-bottom, right-to-left, and thus are bound on the right, while text books are written left-to-right, top-to-bottom, and thus are bound on the left. In mainland China the direction of writing and binding for all books was changed to be like left to right languages in the mid-20th century.

Titling

Early books did not have titles on their spines; rather they were shelved flat with their spines inward and titles written with ink along their fore edges. Modern books display their titles on their spines.

In languages with Chinese-influenced writing systems, the title is written top-to-bottom, as is the language in general. In languages written from left to right, the spine text can be pillar (one letter per line), transverse (text line perpendicular to long edge of spine) and along spine. Conventions differ about the direction in which the title along the spine is rotated:

- Top-to-bottom (descending):

In texts published or printed in the United States, the United Kingdom, the Commonwealth, Scandinavia and the Netherlands, the spine text, when the book is standing upright, runs from the top to the bottom. This means that when the book is lying flat with the front cover upwards, the title is oriented left-to-right on the spine. This practice is reflected in the industry standards ANSI/NISO Z39.41[39] and ISO 6357.[40], but ″... lack of agreement in the matter persisted among English-speaking countries as late as the middle of the twentieth century, when books bound in Britain still tended to have their titles read up the spine ...″.[41]

- Bottom-to-top (ascending):

In most of continental Europe, Latin America, and French Canada the spine text, when the book is standing upright, runs from the bottom up, so the title can be read by tilting the head to the left. This allows the reader to read spines of books shelved in alphabetical order in accordance to the usual way left-to-right and top-to-bottom.[42]

See also

References

- Vaughan 1950, p. xi.

- Robinson 1968, p. 9.

- Harper, Douglas. "book". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- Pugliese Carratelli, Giovanni (1950). "L'Instrumentum Scriptorium nei Monumenti Pompeiani ed Ercolanesi". Pompeiana: raccolta di studi per il secondo centenario degli di Pompei. pp. 166–178.

- Roberts & Skeat 1987, pp. 15–22.

- Skeat 2004, p. 45.

- Turner, Eric (1977). The Typology of the Early Codex. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 38. ISBN 0-8122-7696-5.

- Roberts, Colin H; Skeat, TC (1983). The Birth of the Codex. London: British Academy. pp. 15–22. ISBN 0-19-726061-6.

- "Codex" in The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium, Oxford University Press, New York & Oxford, 1991, p. 473. ISBN 0195046528

- Skeat, T.C. (2004). The Collected Biblical Writings of T.C. Skeat. Leiden: E.J. Brill. p. 45. ISBN 90-04-13920-6.

- Greenfield, Jane (2002). ABC of Bookbinding. New Castle, DE: Oak Knoll Press. pp. 79–117. ISBN 1-884718-41-8.

- Harthan 1950, p. 8.

- Harthan 1950, pp. 8–9.

- Harthan 1950, pp. 8–11.

- Needham, Joseph; Tsien, Tsuen-Hsuin (1985). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 5: Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 1: Paper and Printing. Cambridge University Press. pp. 38–41. ISBN 0-521-08690-6.

- Needham, Joseph; Tsien, Tsuen-Hsuin (1985). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 5: Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 1: Paper and Printing. Cambridge University Press. p. 227. ISBN 0-521-08690-6.

- Needham, Joseph; Tsien, Tsuen-Hsuin (1985). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 5: Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 1: Paper and Printing. Cambridge University Press. pp. 227–229. ISBN 0-521-08690-6.

- Needham, Joseph; Tsien, Tsuen-Hsuin (1985). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 5: Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 1: Paper and Printing. Cambridge University Press. pp. 227–229. ISBN 0-521-08690-6.

- "The Book on Two Legs". Boundless Books and Writingware. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- Piepenbring, Dan (12 November 2015). "A brief history of shelving, and other news". The Paris Review. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- "Aldus Manutius facts, information, pictures | Encyclopedia.com articles about Aldus Manutius". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- Wittmann 2011, p. 269.

-

Erlin, Matt (2010). "How to Think about Luxury Editions in Late Eighteenth- & Early Nineteenth-Century Germany". In Tatlock, Lynne (ed.). Publishing Culture and the "Reading Nation": German Book History in the Long Nineteenth Century. Studies in German Literature Linguistics and Culture Series. 76. Camden House. pp. 25–54. ISBN 9781571134028. Retrieved 19 February 2013.

In most cases, questions related to book-binding did not figure into the discussions between authors and publishers about the formal aspects of editions of their works, because individual purchasers generally made separate arrangements with either the publisher or a bookbinder to have printed sheets bound according to their wishes and their budget.

- See some examples at "Historic Cut-away Binding Structure Models". Book Arts Web. 2013. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- Yale University library exhibition "Islamic Books and Bookbinding"; spread out example from the Brooklyn Museum

- Cyril James, Humphries Davenport (23 January 2006). "English Embroidered Bookbindings". BookRags. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- Miller, Rhonda "Secret Belgian Binding – not a secret anymore" at My Handbound Books – Bookbinding Blog, 19 June 2011

- Parisi, Paul (February 1994). "Methods of Affixing Leaves: Options and Implications". New Library Scene. 13 (1): 8–11, 15.

- "A Dictionary of Descriptive Terminology: self-cover". Stanford University Libraries and Academic Information Resources. Retrieved 22 October 2008.

- Such as the: Centro del bel Libro Archived 26 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine, The Camberwell College of Arts, The London College of Communication, and The North Bennet Street School

- Such as: Columbia College Chicago Archived 12 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine, the University of Alabama, – Nova Scotia College of Art and Design and the University of the Arts in Philadelphia Archived 21 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- "Etherington & Roberts. Dictionary—folder". US Government Printing Office. Retrieved 23 October 2008.

- Leslie, W. (2016). "Bridging the Gap: Artist's Book and Design Bindings by Karen Hanmer". Journal of Artists Books. 39: 47–49.

- "Etherington & Roberts. Dictionary—quire". US Government Printing Office. Retrieved 7 June 2009.

- "Etherington & Roberts. Dictionary—section". US Government Printing Office. Retrieved 17 July 2007.

- "Printing and Book Designs". National Diet Library, Japan. Retrieved 7 June 2009.

- "Etherington & Roberts. Dictionary—sexternion". US Government Printing Office. Retrieved 7 June 2009.

- "Etherington & Roberts. Dictionary—signature". US Government Printing Office. Retrieved 17 July 2007.

- ANSI/NISO Z39.41-1997 Printed Information on Spines Archived 14 November 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ISO 6357 Spine titles on books and other publications, 1985.

- Petroski, Henry (1999). The Book on the Bookshelf. Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-375-40649-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Drösser, Christoph (9 April 2011). "Linksdrehende Bücher". Die Zeit. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- Burdett, Eric (1975). The Craft of Bookbinding: A Practical Handbook. Vancouver, BC: David & Charles Limited. ISBN 978-071536656-1.

- Harthan, John P. (1950). Bookbindings. H.M. Stationery Office – via Victoria and Albert Museum.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Roberts, Colin H.; Skeat, T. C. (1987). The Birth of the Codex. OUP/British Academy. ISBN 978-0-19-726061-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Robinson, Ivor (1968). Introducing Bookbinding. Batsford.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Skeat, Theodore Cressy (2004). Elliot, J. K. (ed.). The Collected Biblical Writings of T. C. Skeat. Brill. ISBN 90-04-13920-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vaughan, Alex J. (1950). Modern Bookbinding: A Treatise Covering Both Letterpress and Stationery Branches of the Trade, with a Section on Finishing and Design. Hale. ISBN 978-0-7090-5820-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wittmann, Reinhard (2011). Geschichte des deutschen Buchhandels [History of the German Book Trade] (in German). C.H.Beck. ISBN 978-3-406-61760-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Brenni, Vito J., compiler. Bookbinding: A Guide to the Literature. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1982. ISBN 0-313-23718-2

- Diehl, Edith. Bookbinding: Its Background and Technique. New York: Dover Publications, 1980. ISBN 0-486-24020-7. (Originally published by Rinehart & Company, 1946 in two volumes.)

- Gross, Henry. Simplified Bookbinding. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, ISBN 0-442-22898-8

- Ikegami, Kojiro. Japanese Bookbinding: Instructions from a Master Craftsman / adapted by Barbara Stephan. New York: Weatherhill, 1986. ISBN 0-8348-0196-5. (Originally published as Hon no tsukuriikata (本のつくり方).)

- Johnson, Arthur W. Manual of Bookbinding. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1978. ISBN 0-684-15332-7

- Johnson, Arthur W. 'The Practical Guide to Craft Bookbinding. London: Thames and Hudson, 1985. ISBN 0-500-27360-X

- Lewis, A. W. Basic Bookbinding. New York: Dover Publications, 1957. ISBN 0-486-20169-4. (Originally published by B.T. Batsford, 1952)

- Smith, Keith A. Non-adhesive Binding: Books Without Paste or Glue. Fairport, NY: Sigma Foundation, 1992. ISBN 0-927159-04-X

- Waller, Ainslie C. "The Guild of Women-Binders", in The Private Library Autumn 1983, published by the Private Libraries Association

- Zeier, Franz. Books, Boxes and Portfolios: Binding Construction, and Design Step-by-Step. New York: Design Press, 1990. ISBN 0-8306-3483-5

- Rossen Petkov, Licheva, Elitsa and others, Binding design and paper conservation of antique books, albums and documents (BBinding), Sofia, 2014. ISBN 978-954-92311-8-2

External links

| Wikibooks has more on the topic of: Bookbinding |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bookbinding. |

- Fine Printing & Binding of the English Bible – Great and Manifold: A Celebration of the Bible in English digital collection, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto

- Book bindings through the ages on Flickr by the National Library of Sweden

- Several free books on Bookbinding, Gilding, Box construction

- Online exhibit of publishers' bookbinding, 1830–1910 from the University of Rochester

- English Embroidered Bookbindings, by Cyril James Humphries Davenport, from Project Gutenberg

- British Library Database of Bookbindings

- Publishers Bindings Online, 1815–1930: The Art of Books

- University of Iowa Libraries Bookbinding Models Digital Collection

- Dorothy Burnett's bookbinding tools – A rich set of tools, ranging in age from 60 years old to 100 years old, used by the first independent craft binder to set up shop in Vancouver, British Columbia, from the UBC Library Digital Collections

- Dutch art nouveau and art deco bookbindings on Anno1900.nl

- UNCG Digital Collections: American Publishers' Trade Bindings

- BBinding project, resources and manuals

- Joseph William Zaehnsdorf, The Art of Bookbinding, 1890

- T. J. Cobden-Sanderson, "Bookbinding" in Arts and Crafts Essays, 1893

- Cobden-Sanderson, T. J. (March 1895). . Popular Science Monthly. 46.

- Davenport, Cyril J. H. (1911). "Bookbinding". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.).

- Museum Libraries. "Bookbinding and Book Collecting". Digital Collections. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art.