Quarto

Quarto (abbreviated Qto, 4to or 4º) is a book or pamphlet produced from full sheets printed with eight pages of text, four to a side, then folded twice to produce four leaves. The leaves are then trimmed along the folds to produce eight book pages. Each printed page presents as one-fourth size of the full sheet.

The earliest known European printed book is a quarto, the Sibyllenbuch, believed to have been printed by Gutenberg in 1452–53, before the Gutenberg Bible, surviving only as a fragment. Quarto is also used as a general description of size of books that are about 12 inches (30 cm) tall, and as such does not necessarily indicate the actual printing format of the books, which may even be unknown as is the case for many modern books. These terms are discussed in greater detail in Book sizes.

Quarto as format

A quarto (from Latin quārtō, ablative form of quārtus, fourth)[2] is a book or pamphlet made up of one or more full sheets of paper on which 8 pages of text were printed, which were then folded two times to produce four leaves. Each leaf of a quarto book thus represents one fourth the size of the original sheet. Each group of 4 leaves (called a "gathering" or "quire") could be sewn through the central fold to attach it to the other gatherings to form a book. Sometimes, additional leaves would be inserted within another group to form, for example, gatherings of 8 leaves, which similarly would be sewn through the central fold. Generally, quartos have more squarish proportions than folios or octavos.[3]

There are variations in how quartos were produced. For example, bibliographers call a book printed as a quarto (four leaves per full sheet) but bound in gatherings of 8 leaves each a "quarto in 8s."[4]

The actual size of a quarto book depends on the size of the full sheet of paper on which it was printed. A demy quarto (abbreviated demy 4to) is a chiefly British term referring to a book size of about 11.25 by 8.75 inches (286 by 222 mm), a medium quarto 9 by 11.5 inches (230 by 290 mm), a royal quarto 10 by 12.5 inches (250 by 320 mm), and a small quarto equalled a square octavo, all untrimmed.[5]

The earliest surviving books printed by movable type by Gutenberg are quartos, which were printed before the Gutenberg Bible. The earliest known one is a fragment of a medieval poem called the Sibyllenbuch, believed to have been printed by Gutenberg in 1452–53.[6][7] Quartos were the most common format of books printed in the incunabula period (books printed before 1501).[8] The British Library Incunabula Short Title Catalogue currently lists about 28,100 different editions of surviving books, pamphlets and broadsides (some fragmentary only) printed before 1501,[9] of which about 14,360 are quartos,[10] representing just over half of all works in the catalogue.

Quarto as size

Beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, technology permitted the manufacture of large sheets or rolls of paper on which books were printed, many text pages at a time. As a result, it may be impossible to determine the actual format (i.e., number of leaves formed from each sheet fed into a press). The term "quarto" as applied to such books may refer simply to the size, i.e., books that are approximately 10 inches (250 mm) tall by 8 inches (200 mm) wide.

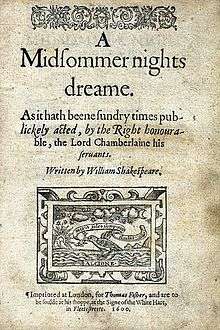

Quartos for separate plays and poems

During the Elizabethan era and through the mid-seventeenth century, plays and poems were commonly printed as separate works in quarto format. Eighteen of Shakespeare's 36 plays included in first folio collected edition of 1623, were previously separately printed as quartos, with a single exception that was printed in octavo.[11] For example, Shakespeare's Henry IV, Part 1, the most popular play of the era, was first published as a quarto in 1598, with a second quarto edition in 1599, followed by a number of subsequent quarto editions. Bibliographers have extensively studied these different editions, which they refer to by abbreviations such as Q1, Q2, etc. The texts of some of the Shakespeare quartos are highly inaccurate and are full of errors and omissions. Bibliographer Alfred W. Pollard named those editions Bad quartos, and it is speculated that they may have been produced, not from manuscript texts, but from actors who had memorized their lines.

Other playwrights in this period also published their plays in quarto editions. Christopher Marlowe's Doctor Faustus, for example, was published as a quarto in 1604 (Q1), with a second quarto edition in 1609. The same is true of poems, Shakespeare's poem Venus and Adonis being first printed as a quarto in 1593 (Q1), with a second quarto edition (Q2) in 1594.

In Spanish culture, a similar concept of separate editions of plays is known as comedia suelta.

See also

References

- Folger Shakespeare Library

- Oxford English Dictionary, 2d ed, (1989), on line access.

- McKerrow, p. 164.

- McKerrow, p. 28.

- Chambers English Dictionary

- British Library, Incunabula Short Title Catalogue, entry for the Sybyllenbuch.

- Margaret Bingham Stillwell, The Beginning of the World of Books, 1450–1470, Bibliographical Society of America, New York, 1972, pp. 3–4, described as a medieval poem printed in about 1451–52, but not identifying the format.

- British Library, Incunabula Short Title Catalogue, search for format as "4to", sorted by year

- Search of Incunabula Short Title Catalog for imprints before 1501, sorted by date. Search done July 12, 2009.

- British Library, Incunabula Short Title Catalogue, search for imprints before 1501 and format as "4to", sorted by year. Search done July 12, 2009.

- The exception was the 1595 first edition of Henry VI, Part 3, in the version known as The True Tragedy of Richard Duke of York; it was an octavo, not a quarto.

Sources

- McKerrow, R. (1927) An Introduction to Bibliography for Literary Students, Oxford University Press: Oxford.