Leatherback sea turtle

The leatherback sea turtle (Dermochelys coriacea), sometimes called the lute turtle or leathery turtle or simply the luth, is the largest of all living turtles and is the fourth-heaviest modern reptile behind three crocodilians.[5][6] It is the only living species in the genus Dermochelys and family Dermochelyidae. It can easily be differentiated from other modern sea turtles by its lack of a bony shell, hence the name. Instead, its carapace is covered by skin and oily flesh.

| Leatherback sea turtle | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Testudines |

| Suborder: | Cryptodira |

| Superfamily: | Chelonioidea |

| Family: | Dermochelyidae |

| Subfamily: | Dermochelyinae |

| Genus: | Dermochelys Blainville, 1816[3] |

| Species: | D. coriacea |

| Binomial name | |

| Dermochelys coriacea | |

| |

| Synonyms[4] | |

|

List of synonyms

| |

Taxonomy and evolution

Taxonomy

Dermochelys coriacea is the only species in genus Dermochelys. The genus, in turn, contains the only extant member of the family Dermochelyidae.[7]

Domenico Agostino Vandelli named the species first in 1761 as Testudo coriacea after an animal captured at Ostia and donated to the University of Padua by Pope Clement XIII.[8] In 1816, French zoologist Henri Blainville coined the term Dermochelys. The leatherback was then reclassified as Dermochelys coriacea.[9] In 1843, the zoologist Leopold Fitzinger put the genus in its own family, Dermochelyidae.[10] In 1884, the American naturalist Samuel Garman described the species as Sphargis coriacea schlegelii.[11] The two were then united in D. coriacea, with each given subspecies status as D. c. coriacea and D. c. schlegelii. The subspecies were later labeled invalid synonyms of D. coriacea.[12][13]

Both the turtle's common and scientific names come from the leathery texture and appearance of its carapace (Dermochelys coriacea literally translates to "Leathery Skin-turtle"). Older names include "leathery turtle"[6] and "trunk turtle".[14] The common names incorporating "lute" and "luth" compare the seven ridges that run the length of the animal's back to the seven strings on the musical instrument of the same name.[15] But probably more accurately derived from the lute's ribbed back which is in the form of a shell.

Evolution

Relatives of modern leatherback turtles have existed in relatively the same form since the first true sea turtles evolved over 110 million years ago during the Cretaceous period.[16] The dermochelyids are relatives of the family Cheloniidae, which contains the other six extant sea turtle species. However, their sister taxon is the extinct family Protostegidae that included other species that did not have a hard carapace.[17][18]

Anatomy and physiology

Leatherback turtles have the most hydrodynamic body design of any sea turtle, with a large, teardrop-shaped body. A large pair of front flippers powers the turtles through the water. Like other sea turtles, the leatherback has flattened forelimbs adapted for swimming in the open ocean. Claws are absent from both pairs of flippers. The leatherback's flippers are the largest in proportion to its body among extant sea turtles. Leatherback's front flippers can grow up to 2.7 m (8.9 ft) in large specimens, the largest flippers (even in comparison to its body) of any sea turtle.

The leatherback has several characteristics that distinguish it from other sea turtles. Its most notable feature is the lack of a bony carapace. Instead of scutes, it has thick, leathery skin with embedded minuscule osteoderms. Seven distinct ridges rise from the carapace, crossing from the cranial to caudal margin of the turtle's back. Leatherbacks are unique among reptiles in that their scales lack β-keratin. The entire turtle's dorsal surface is colored dark grey to black, with a scattering of white blotches and spots. Demonstrating countershading, the turtle's underside is lightly colored.[19][20] Instead of teeth, the leatherback turtle has points on the tomium of its upper lip, with backwards spines in its throat (esophagus) to help it swallow food and to stop its prey from escaping once caught.

D. coriacea adults average 1–1.75 m (3.3–5.7 ft) in curved carapace length (CCL), 1.83–2.2 m (6.0–7.2 ft) in total length, and 250 to 700 kg (550 to 1,540 lb) in weight.[19][21] In the Caribbean, the mean size of adults was reported at 384 kg (847 lb) in weight and 1.55 m (5.1 ft) in CCL.[22] Similarly, those nesting in French Guiana, weighed an average of 339.3 kg (748 lb) and measured 1.54 m (5.1 ft) in CCL.[23][24] The largest verified specimen ever found was discovered on the Pakistani beach of Sandspit and measured 213 cm (6.99 ft) in CCL and 650 kg (1,433 lb) in weight.[25] A previous contender, the "Harlech turtle", was purportedly 256.5 cm (8.42 ft) in CCL and 916 kg (2,019 lb) in weight,[26][27] however recent inspection of its remains housed at the National Museum Cardiff have found that its true CCL is closer to 1.5 m (4.9 ft), casting doubt on the accuracy of the claimed weight, as well.[25] On the other hand, one scientific paper has claimed that the species can weigh up to 1,000 kg (2,200 lb) without providing more verifiable detail.[28] The leatherback turtle is scarcely larger than any other sea turtle upon hatching, as they average 61.3 mm (2.41 in) in carapace length and weigh around 46 g (1.6 oz) when freshly hatched.[22]

D. coriacea exhibits several anatomical characteristics believed to be associated with a life in cold waters, including an extensive covering of brown adipose tissue,[29] temperature-independent swimming muscles,[30] countercurrent heat exchangers between the large front flippers and the core body, and an extensive network of countercurrent heat exchangers surrounding the trachea.[31]

Physiology

Leatherbacks have been viewed as unique among extant reptiles for their ability to maintain high body temperatures using metabolically generated heat, or endothermy. Initial studies on their metabolic rates found leatherbacks had resting metabolisms around three times higher than expected for reptiles of their size.[32] However, recent studies using reptile representatives encompassing all the size ranges leatherbacks pass through during ontogeny discovered the resting metabolic rate of a large D. coriacea is not significantly different from predicted results based on allometry.[33]

Rather than using a high resting metabolism, leatherbacks appear to take advantage of a high activity rate. Studies on wild D. coriacea discovered individuals may spend as little as 0.1% of the day resting.[34] This constant swimming creates muscle-derived heat. Coupled with their countercurrent heat exchangers, insulating fat covering, and large size, leatherbacks are able to maintain high temperature differentials compared to the surrounding water. Adult leatherbacks have been found with core body temperatures that were 18 °C (32 °F) above the water in which they were swimming.[35]

Leatherback turtles are one of the deepest-diving marine animals. Individuals have been recorded diving to depths as great as 1,280 m (4,200 ft).[36][37] Typical dive durations are between 3 and 8 minutes, with dives of 30–70 minutes occurring infrequently.[38]

They are also the fastest-moving reptiles. The 1992 edition of the Guinness Book of World Records lists the leatherback turtle moving at 35.28 km/h (21.92 mph) in the water.[39][40] More typically, they swim at 1.80–10.08 km/h (1.12–6.26 mph).[34]

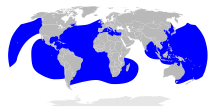

Distribution

The leatherback turtle is a species with a cosmopolitan global range. Of all the extant sea turtle species, D. coriacea has the widest distribution, reaching as far north as Alaska and Norway and as far south as Cape Agulhas in Africa and the southernmost tip of New Zealand.[19] The leatherback is found in all tropical and subtropical oceans, and its range extends well into the Arctic Circle.[41]

The three major, genetically distinct populations occur in the Atlantic, eastern Pacific, and western Pacific Oceans.[5][42] While nesting beaches have been identified in the region, leatherback populations in the Indian Ocean remain generally unassessed and unevaluated.[43]

Recent estimates of global nesting populations are that 26,000 to 43,000 females nest annually, which is a dramatic decline from the 115,000 estimated in 1980.[44]

Atlantic subpopulation

The leatherback turtle population in the Atlantic Ocean ranges across the entire region. They range as far north as the North Sea and to the Cape of Good Hope in the south. Unlike other sea turtles, leatherback feeding areas are in colder waters, where an abundance of their jellyfish prey is found, which broadens their range. However, only a few beaches on both sides of the Atlantic provide nesting sites.[45]

Off the Atlantic coast of Canada, leatherback turtles feed in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence near Quebec and as far north as Newfoundland and Labrador.[46] The most significant Atlantic nesting sites are in Suriname, Guyana, French Guiana in South America, Antigua and Barbuda, and Trinidad and Tobago in the Caribbean, and Gabon in Central Africa. The beaches of Mayumba National Park in Mayumba, Gabon, host the largest nesting population on the African continent and possibly worldwide, with nearly 30,000 turtles visiting its beaches each year between October and April.[42][47][47] Off the northeastern coast of the South American continent, a few select beaches between French Guiana and Suriname are primary nesting sites of several species of sea turtles, the majority being leatherbacks.[23] A few hundred nest annually on the eastern coast of Florida.[6] In Costa Rica, the beaches of Gandoca and Parismina provide nesting grounds.[43][48]

Pacific subpopulation

Pacific leatherbacks divide into two populations. One population nests on beaches in Papua, Indonesia, and the Solomon Islands, and forages across the Pacific in the Northern Hemisphere, along the coasts of California, Oregon, and Washington in North America. The eastern Pacific population forages in the Southern Hemisphere, in waters along the western coast of South America, nesting in Mexico, Panama, El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica.[42][49]

The continental United States offers two major Pacific leatherback feeding areas. One well-studied area is just off the northwestern coast near the mouth of the Columbia River. The other American area is located in California.[49] Further north, off the Pacific coast of Canada, leatherbacks visit the beaches of British Columbia.[46]

Estimates by the WWF suggest only 2,300 adult females of the Pacific leatherback remain, making it the most endangered marine turtle subpopulation.[50]

South China Sea subpopulation

A third possible Pacific subpopulation has been proposed, those that nest in Malaysia. This subpopulation, however, has effectively been eradicated. The beach of Rantau Abang in Terengganu, Malaysia, once had the largest nesting population in the world, hosting 10,000 nests per year. The major cause of the decline was egg consumption by humans. Conservation efforts initiated in the 1960s were ineffective because they involved excavating and incubating eggs at artificial sites which inadvertently exposed the eggs to high temperatures. It only became known in the 1980s that sea turtles undergo temperature-dependent sex determination; it is suspected that nearly all the artificially incubated hatchlings were female.[51] In 2008, two turtles nested at Rantau Abang, and unfortunately, the eggs were infertile.

Indian Ocean subpopulation

While little research has been done on Dermochelys populations in the Indian Ocean, nesting populations are known from Sri Lanka and the Nicobar Islands. These turtles are proposed to form a separate, genetically distinct Indian Ocean subpopulation.[43]

Ecology and life history

.jpg)

Habitat

Leatherback sea turtles can be found primarily in the open ocean. Scientists tracked a leatherback turtle that swam from Jen Womom beach of Tambrauw Regency in West Papua of Indonesia to the U.S. in a 20,000 km (12,000 mi) foraging journey over a period of 647 days.[19][52] Leatherbacks follow their jellyfish prey throughout the day, resulting in turtles "preferring" deeper water in the daytime, and shallower water at night (when the jellyfish rise up the water column).[34] This hunting strategy often places turtles in very frigid waters. One individual was found actively hunting in waters that had a surface temperature of 0.4 °C. (32.72 °F).[53] Leatherback turtles are known to pursue prey deeper than 1000 m—beyond the physiological limits of all other diving tetrapods except for beaked whales and sperm whales.[54]

Their favored breeding beaches are mainland sites facing the deep water, and they seem to avoid those sites protected by coral reefs.[55]

Feeding

Adult D. coriacea turtles subsist almost entirely on jellyfish.[19] Due to their obligate feeding nature, leatherbacks help control jellyfish populations.[5] Leatherbacks also feed on other soft-bodied organisms, such as tunicates and cephalopods.[56]

Pacific leatherbacks migrate about 6,000 mi (9,700 km) across the Pacific from their nesting sites in Indonesia to eat California jellyfish. One cause for their endangered state is plastic bags floating in the ocean. Pacific leatherback sea turtles mistake these plastic bags for jellyfish; an estimated one-third of adults have ingested plastic.[57] Plastic enters the oceans along the west coast of urban areas, where leatherbacks forage, with Californians using upward of 19 billion plastic bags every year.[58]

Several species of sea turtles commonly ingest plastic marine debris, and even small quantities of debris can kill sea turtles by obstructing their digestive tracts.[59] Nutrient dilution, which occurs when plastics displace food in the gut, affects the nutrient gain and consequently the growth of sea turtles.[60] Ingestion of marine debris and slowed nutrient gain leads to increased time for sexual maturation that may affect future reproductive behaviors.[61] These turtles have the highest risk of encountering and ingesting plastic bags offshore of San Francisco Bay, the Columbia River mouth, and Puget Sound.

Lifespan

Very little is known of the species' lifespan. Some reports claim "30 years or more",[62] while others state "50 years or more".[63] Upper estimates exceed 100 years.[64]

Death and decomposition

Dead leatherbacks that wash ashore are microecosystems while decomposing. In 1996, a drowned carcass held sarcophagid and calliphorid flies after being picked open by a pair of Coragyps atratus vultures. Infestation by carrion-eating beetles of the families Scarabaeidae, Carabidae, and Tenebrionidae soon followed. After days of decomposition, beetles from the families Histeridae and Staphylinidae and anthomyiid flies invaded the corpse, as well. Organisms from more than a dozen families took part in consuming the carcass.[65]

Life history

Predation

Leatherback turtles face many predators in their early lives. Eggs may be preyed on by a diversity of coastal predators, including ghost crabs, monitor lizards, raccoons, coatis, dogs, coyotes, genets, mongooses, and shorebirds ranging from small plovers to large gulls. Many of the same predators feed on baby turtles as they try to get to the ocean, as well as frigatebirds and varied raptors. Once in the ocean, young leatherbacks still face predation from cephalopods, requiem sharks, and various large fish. Despite their lack of a hard shell, the huge adults face fewer serious predators, though they are occasionally overwhelmed and preyed on by very large marine predators such as killer whales, great white sharks, and tiger sharks. Nesting females have been preyed upon by jaguars in the American tropics.[66][67][68]

The adult leatherback has been observed aggressively defending itself at sea from predators. A medium-sized adult was observed chasing a shark that had attempted to bite it and then turned its aggression and attacked the boat containing the humans observing the prior interaction.[69] Dermochelys juveniles spend more of their time in tropical waters than do adults.[56]

Adults are prone to long-distance migration. Migration occurs between the cold waters where mature leatherbacks feed, to the tropical and subtropical beaches in the regions where they hatch. In the Atlantic, females tagged in French Guiana have been recaptured on the other side of the ocean in Morocco and Spain.[23]

Mating

Mating takes place at sea. Males never leave the water once they enter it, unlike females, which nest on land. After encountering a female (which possibly exudes a pheromone to signal her reproductive status), the male uses head movements, nuzzling, biting, or flipper movements to determine her receptiveness. Males can mate every year but the females mate every two to three years. Fertilization is internal, and multiple males usually mate with a single female. This polyandry does not provide the offspring with any special advantages.[70]

Offspring

While other sea turtle species almost always return to their hatching beach, leatherbacks may choose another beach within the region. They choose beaches with soft sand because their softer shells and plastrons are easily damaged by hard rocks. Nesting beaches also have shallower approach angles from the sea. This is a vulnerability for the turtles because such beaches easily erode. They nest at night when the risk of predation and heat stress is lowest. As leatherback turtles spend the vast majority of their lives in the ocean, their eyes are not well adapted to night vision on land. The typical nesting environment includes a dark forested area adjacent to the beach. The contrast between this dark forest and the brighter, moonlit ocean provides directionality for the females. They nest towards the dark and then return to the ocean and the light.

Females excavate a nest above the high-tide line with their flippers. One female may lay as many as nine clutches in one breeding season. About nine days pass between nesting events. Average clutch size is around 110 eggs, 85% of which are viable.[19] After laying, the female carefully back-fills the nest, disguising it from predators with a scattering of sand.[56][71]

Development of offspring

Cleavage of the cell begins within hours of fertilization, but development is suspended during the gastrulation period of movements and infoldings of embryonic cells, while the eggs are being laid. Development then resumes, but embryos remain extremely susceptible to movement-induced mortality until the membranes fully develop after incubating for 20 to 25 days. The structural differentiation of body and organs (organogenesis) soon follows. The eggs hatch in about 60 to 70 days. As with other reptiles, the nest's ambient temperature determines the sex of the hatchings. After nightfall, the hatchings dig to the surface and walk to the sea.[72][73]

Leatherback nesting seasons vary by location; it occurs from February to July in Parismina, Costa Rica. Farther east in French Guiana, nesting is from March to August. Atlantic leatherbacks nest between February and July from South Carolina in the United States to the United States Virgin Islands in the Caribbean and to Suriname and Guyana.[74]

Importance to humans

People around the world still harvest sea turtle eggs. Asian exploitation of turtle nests has been cited as the most significant factor for the species' global population decline. In Southeast Asia, egg harvesting in countries such as Thailand and Malaysia has led to a near-total collapse of local nesting populations.[75] In Malaysia, where the turtle is practically locally extinct, the eggs are considered a delicacy.[76] In the Caribbean, some cultures consider the eggs to be aphrodisiacs.[75]

They are also a major jellyfish predator,[50][77] which helps keep populations in check. This bears importance to humans, as jellyfish diets consist largely of larval fish, the adults of which are commercially fished by humans.[78]

Cultural significance

The turtle is known to be of cultural significance to tribes all over the world. The Seri people, from the Mexican state of Sonora, find the leatherback sea turtle culturally significant because it is one of their five main creators. The Seri people devote ceremonies and fiestas to the turtle when one is caught and then released back into the environment.[79] The Seri people have noticed the drastic decline in turtle populations over the years and created a conservation movement to help this. The group, made up of both youth and elders from the tribe, is called Grupo Tortuguero Comaac. They use both traditional ecological knowledge and Western technology to help manage the turtle populations and protect the turtle's natural environment.[80]

In the Malaysian state of Terengganu, the turtle is the state's main animal and is usually seen in tourism ads.

Conservation

Leatherback turtles have few natural predators once they mature; they are most vulnerable to predation in their early life stages. Birds, small mammals, and other opportunists dig up the nests of turtles and consume eggs. Shorebirds and crustaceans prey on the hatchings scrambling for the sea. Once they enter the water, they become prey to predatory fish and cephalopods.

Leatherbacks have slightly fewer human-related threats than other sea turtle species. Their flesh contains too much oil and fat to be considered palatable, reducing the demand. However, human activity still endangers leatherback turtles in direct and indirect ways. Directly, a few are caught for their meat by subsistence fisheries. Nests are raided by humans in places such as Southeast Asia.[75] In the state of Florida, there have been 603 leatherback strandings between 1980 and 2014. Almost one-quarter (23.5%) of leatherback strandings are due to vessel-strike injuries, which is the highest cause of strandings.[81]

Light pollution is a serious threat to sea turtle hatchlings which have a strong attraction to light. Human-generated light from streetlights and buildings causes hatchlings to become disoriented, crawling toward the light and away from the beach. Hatchlings are attracted to light because the lightest area on a natural beach is the horizon over the ocean, the darkest area is the dunes or forest. On Florida's Atlantic coast, some beaches with high turtle nesting density have lost thousands of hatchlings due to artificial light.[82]

Many human activities indirectly harm Dermochelys populations. As a pelagic species, D. coriacea is occasionally caught as bycatch. Entanglement in lobster pot ropes is another hazard the animals face.[83] As the largest living sea turtles, turtle excluder devices can be ineffective with mature adults. In the eastern Pacific alone, a reported average of 1,500 mature females were accidentally caught annually in the 1990s.[75] Pollution, both chemical and physical, can also be fatal. Many turtles die from malabsorption and intestinal blockage following the ingestion of balloons and plastic bags which resemble their jellyfish prey.[19] Chemical pollution also has an adverse effect on Dermochelys. A high level of phthalates has been measured in their eggs' yolks.[75]

Global initiatives

D. coriacea is listed on CITES Appendix I, which makes export/import of this species (including parts) illegal. It has been listed as an EDGE species by the Zoological Society of London.[84]

The species is listed in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species as VU (Vulnerable),[1] and additionally with the following infraspecific taxa assessments:

- East Pacific Ocean subpopulation: CR (Critically Endangered)[85]

- Northeast Indian Ocean subpopulation: DD (Data Deficient)[86]

- Northwest Atlantic Ocean subpopulation: EN (Endangered)[87]

- Southeast Atlantic Ocean subpopulation: DD (Data Deficient)[88]

- Southwest Atlantic Ocean subpopulation CR (Critically Endangered)[89]

- Southwest Indian Ocean subpopulation CR (Critically Endangered)[90]

- West Pacific Ocean subpopulation CR (Critically Endangered)[91]

Conserving Pacific and Eastern Atlantic populations were included among the top-ten issues in turtle conservation in the first State of the World's Sea Turtles report published in 2006. The report noted significant declines in the Mexican, Costa Rican, and Malaysian populations. The eastern Atlantic nesting population was threatened by increased fishing pressures from eastern South American countries.[92]

The Leatherback Trust was founded specifically to conserve sea turtles, specifically its namesake. The foundation established a sanctuary in Costa Rica, the Parque Marino Las Baulas.[93]

National and local initiatives

The leatherback sea turtle is subject to differing conservation laws in various countries.

The United States listed it as an endangered species on 2 June 1970. The passing of the Endangered Species Act of 1973 ratified its status.[94] In 2012, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration designated 41,914 square miles of Pacific Ocean along California, Oregon, and Washington as "critical habitat".[95] In Canada, the Species at Risk Act made it illegal to exploit the species in Canadian waters. The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada classified it as endangered.[46] Ireland and Wales initiated a joint leatherback conservation effort between Swansea University and University College Cork. Funded by the European Regional Development Fund, the Irish Sea Leatherback Turtle Project focuses on research such as tagging and satellite tracking of individuals.[96]

Earthwatch Institute, a global nonprofit that teams volunteer with scientists to conduct important environmental research, launched a program called "Trinidad's Leatherback Sea Turtles". This program strives to help save the world's largest turtle from extinction in Matura Beach, Trinidad, as volunteers work side-by-side with leading scientists and a local conservation group, Nature Seekers. This tropical island off the coast of Venezuela is known for its vibrant ethnic diversity and rich cultural events. It is also the site of one of the most important nesting beaches for endangered leatherback turtles, enormous reptiles that can weigh a ton and dive deeper than many whales. Each year, more than 2,000 female leatherbacks haul themselves onto Matura Beach to lay their eggs. With leatherback populations declining more quickly than any other large animal in modern history, each turtle is precious. On this research project, Dr. Dennis Sammy of Nature Seekers and Dr. Scott Eckert of Wider Caribbean Sea Turtle Conservation Network work alongside a team of volunteers to help prevent the extinction of leatherback sea turtles.[97]

Several Caribbean countries started conservation programs, such as the St. Kitts Sea Turtle Monitoring Network, focused on using ecotourism to highlight the leatherback's plight. On the Atlantic coast of Costa Rica, the village of Parismina has one such initiative. Parismina is an isolated sandbar where a large number of leatherbacks lay eggs, but poachers abound. Since 1998, the village has been assisting turtles with a hatchery program. The Parismina Social Club is a charitable organization backed by American tourists and expatriates, which collects donations to fund beach patrols.[98][99] In Dominica, patrollers from DomSeTCo protect leatherback nesting sites from poachers.

Mayumba National Park in Gabon, Central Africa, was created to protect Africa's most important nesting beach. More than 30,000 turtles nest on Mayumba's beaches between September and April each year.[47]

In mid-2007, the Malaysian Fisheries Department revealed a plan to clone leatherback turtles to replenish the country's rapidly declining population. Some conservation biologists, however, are skeptical of the proposed plan because cloning has only succeeded on mammals such as dogs, sheep, cats, and cattle, and uncertainties persist about cloned animals' health and lifespans.[100] Leatherbacks used to nest in the thousands on Malaysian beaches, including those at Terengganu, where more than 3,000 females nested in the late 1960s.[101] The last official count of nesting leatherback females on that beach was recorded to be a mere two females in 1993.[42]

In Brazil, reproduction of the leatherback turtle is being assisted by the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources' projeto TAMAR (TAMAR project), which works to protect nests and prevent accidental kills by fishing boats. The last official count of nesting leatherback females in Brazil yielded only seven females.[102] In January 2010, one female at Pontal do Paraná laid hundreds of eggs. Since leatherback sea turtles had been reported to nest only at Espírito Santo's shore, but never in the state of Paraná, this unusual act brought much attention to the area, biologists have been protecting the nests and checking their eggs' temperature, although it might be that none of the eggs are fertile.[103]

Australia's Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 lists D. coriacea as vulnerable, while Queensland's Nature Conservation Act 1992 lists it as endangered.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dermochelys coriacea. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Dermochelys coriacea |

References

- Wallace, B.P.; Tiwari, M. & Girondot, M. (2013). "Dermochelys coriacea". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2013: e.T6494A43526147. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013-2.RLTS.T6494A43526147.en.

- https://ecos.fws.gov/ecp0/reports/ad-hoc-species-report-input

- Rhodin, A. G. J.; van Dijk, P. P.; Inverson, J. B.; Shaffer, H. B. (14 December 2010). Turtles of the world, 2010 update: Annotated checklist of taxonomy, synonymy, distribution and conservation status (PDF). Chelonian Research Monographs. 5. p. 000.xx. doi:10.3854/crm.5.000.checklist.v3.2010. ISBN 978-0965354097. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 December 2010.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Uwe, Fritz; Havaš, Peter (2007). "Checklist of Chelonians of the World" (PDF). Vertebrate Zoology. 57 (2): 174–176. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 December 2010. Retrieved 29 May 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "WWF - Leatherback turtle". Marine Turtles. World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF). 16 February 2007. Retrieved 9 September 2007.

- "The Leatherback Turtle (Dermochelys coriacea)". turtles.org. 24 January 2004. Retrieved 15 September 2007.

- "Dermochelys coriacea". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 14 September 2007.

- "Testudo coriacea". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 14 September 2007.

- "Dermochelys". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 14 September 2007.

- "Dermochelyidae". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 14 September 2007.

- "Sphargis coriacea schlegelii". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 14 September 2007.

- "Dermochelys coriacea coriacea". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 14 September 2007.

- "Dermochelys coriacea schlegelii". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 14 September 2007.

- Dundee, Harold A. (2001). "The Etymological Riddle of the Ridley Sea Turtle". Marine Turtle Newsletter. 58: 10–12. Retrieved 30 December 2008.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Giant turtle a captive". Weekly Times (Melbourne, Vic. : 1869 - 1954). 3 March 1954. p. 40. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- Godfrey, Matthew (2018). "Leatherback Sea Turtle" (PDF). North Carolina Wildlife Profiles.

- Haaramo, Miiko (15 August 2003). "Dermochelyoidea - leatherback turtles and relatives". Miiko's Phylogeny Archive. Finnish Museum of the Natural History. Archived from the original on 25 June 2007. Retrieved 15 September 2007.

- Hirayama R. (16 April 1998). "Oldest known sea turtle". Nature. 392 (6677): 705–708. Bibcode:1998Natur.392..705H. doi:10.1038/33669.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Species Fact Sheet: Leatherback Sea Turtle". Caribbean Conservation Corporation & Sea Turtle Survival League. Caribbean Conservation Corporation. 29 December 2005. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 6 September 2007.

- Fontanes, F. (2003). "ADW: Dermochelys coriacea: Information". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Retrieved 17 September 2007.

- Wood, Gerald (1983). The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats. Enfield, Middlesex : Guinness Superlatives. ISBN 978-0-85112-235-9.

- http://www.dnr.sc.gov/cwcs/pdf/Leatherbacktutle.pdf

- Girondot M, Fretey J (1996). "Leatherback turtles, Dermochelys coriacea, nesting in French Guiana, 1978–1995". Chelonian Conservation and Biology. 2: 204–208. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 14 September 2007.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Georges, J. Y., & Fossette, S. (2006). Estimating body mass in the leatherback turtle Dermochelys coriacea. arXiv preprint q-bio/0611055.

- McClain, CR; Balk, MA; Benfield, MC; Branch, TA; Chen, C; Cosgrove, J; Dove, ADM; Gaskins, LC; Helm, RR; Hochberg, FG; Lee, FB; Marshall, A; McMurray, SE; Schanche, C; Stone, SN; Thaler, AD (2015). "Sizing ocean giants: patterns of intraspecific size variation in marine megafauna". PeerJ. 3: e715. doi:10.7717/peerj.715. PMC 4304853. PMID 25649000.

- Eckert KL, Luginbuhl C (1988). "Death of a Giant". Marine Turtle Newsletter. 43: 2–3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- George, R (1996). "Age and growth in leatherback turtles, Dermochelys coriacea (Testudines: Dermochelyidae): a skeletochronological analysis". Chelonian Conservation and Biology. 2 (2): 244–249.

- Reina, R. D.; Mayor, P. A.; Spotila, J. R.; Piedra, R.; Paladino, F. V. (2002). "Nesting ecology of the leatherback turtle, Dermochelys coriacea, at Parque Nacional Marino Las Baulas, Costa Rica: 1988-1989 to 1999-2000". Copeia. 2002 (3): 653–664. doi:10.1643/0045-8511(2002)002[0653:neotlt]2.0.co;2.

- Goff GP, Stenson GB (1988). "Brown Adipose Tissue in Leatherback Sea Turtles: A Thermogenic Organ in an Endothermic Reptile". Copeia. 1988 (4): 1071–1075. doi:10.2307/1445737. JSTOR 1445737.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Penick DN, Spotila JR, O'Connor MP, Steyermark AC, George RH, Salice CJ, Paladino FV (1998). "Thermal Independence of Muscle Tissue Metabolism in the Leatherback Turtle, Dermochelys coriacea". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology A. 120 (3): 399–403. doi:10.1016/S1095-6433(98)00024-5. PMID 9787823.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Davenport J, Fraher J, Fitzgerald E, McLaughlin P, Doyle T, Harman L, Cuffe T, Dockery P (2009). "Ontogenetic Changes in Tracheal Structure Facilitate Deep Dives and Cold Water Foraging in Adult Leatherback Sea Turtles". Journal of Experimental Biology. 212 (Pt 21): 3440–3447. doi:10.1242/jeb.034991. PMID 19837885.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Paladino FV, O'Connor MP, Spotila JR (1990). "Metabolism of Leatherback Turtles, Gigantothermy, and Thermoregulation of Dinosaurs". Nature. 344 (6269): 858–860. Bibcode:1990Natur.344..858P. doi:10.1038/344858a0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wallace BP, Jones TT (2008). "What Makes Marine Turtles Go: A Review of Metabolic Rates and their Consequences". Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology. 356 (1–2): 8–24. doi:10.1016/j.jembe.2007.12.023.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Eckert SA (2002). "Swim Speed and Movement Patterns of Gravid Leatherback Sea Turtles (Dermochelys coriacea) at St Croix, US Virgin Islands". Journal of Experimental Biology. 205 (Pt 23): 3689–3697. PMID 12409495.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Frair W, Ackman RG, Mrosovsky N (1972). "Body Temperatures of Dermochelys coriacea: Warm Turtle from Cold Water". Science. 177 (4051): 791–793. Bibcode:1972Sci...177..791F. doi:10.1126/science.177.4051.791. PMID 17840128.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Doyle TK, Houghton JD, O'Súilleabháin PF, Hobson VJ, Marnell F, Davenport J, Hays GC (2008). "Leatherback Turtles Satellite Tagged in European Waters". Endangered Species Research. 4: 23–31. doi:10.3354/esr00076. hdl:10536/DRO/DU:30058338.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Leatherbacks home". Daily News Tribune. Daily News Tribune. 31 July 2008. Retrieved 16 November 2008.

- Alessandro Sale; Luschi, Paolo; Mencacci, Resi; Lambardi, Paolo; Hughes, George R.; Hays, Graeme C.; Benvenuti, Silvano; Papi, Floriano (2006). "Long-term monitoring of leatherback turtle diving behaviour during oceanic movements" (PDF). Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology. 328 (2): 197–210. doi:10.1016/j.jembe.2005.07.006. Retrieved 31 May 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shweky, Rachel (1999). "Speed of a Turtle or Tortoise". The Physics Factbook. Retrieved 13 September 2007.

- McFarlan, Donald (1991). Guinness Book of Records 1992. New York: Guinness.

- Willgohs JF (1957). "Occurrence of the Leathery Turtle in the Northern North Sea and off Western Norway". Nature. 179 (4551): 163–164. Bibcode:1957Natur.179..163W. doi:10.1038/179163a0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "WWF - Leatherback turtle - Population & Distribution". Marine Turtles. World Wide Fund for Nature. 16 February 2007. Archived from the original on 9 August 2007. Retrieved 13 September 2007.

- Dutton P (2006). "Building our Knowledge of the Leatherback Stock Structure" (PDF). The State of the World's Sea Turtles Report. 1: 10–11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 May 2011. Retrieved 5 February 2019.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Leatherback Sea Turtle-Fact Sheet". U.S Fish & Wildlife Service-North Florida Office. 31 August 2007.

- Caut, Stéphane; Guirlet, Elodie; Angulo, Elena; Das, Krishna; Girondot, Marc (25 March 2008). "Isotope Analysis Reveals Foraging Area Dichotomy for Atlantic Leatherback Turtles". PLoS ONE. 3 (3): e1845. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.1845C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001845. PMC 2267998. PMID 18365003.

- "Nova Scotia Leatherback Turtle Working Group". Nova Scotia Leatherback Turtle Working Group. 2007. Retrieved 13 September 2007.

- "Marine Turtles". Mayumba National Park: Protecting Gabon's Wild Coast. Mayumba National Park. 2006. Retrieved 13 September 2007.

- "Sea Turtles of Parismina". Village of Parismina, Costa Rica - Turtle Project. Parismina Social Club. 13 May 2007. Archived from the original on 11 September 2007. Retrieved 13 September 2007.

- Profita, Cassandra (1 November 2006). "Saving the 'dinosaurs of the sea'". Headline News. The Daily Astorian. Retrieved 7 September 2007.

- "WWF - Leathetback turtle". panda.org. WWF - World Wide Fund For Nature. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

- Heng, Natalie Hope remains in conserving Malaysia’s three turtle species Archived 25 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine. The Star Malaysia, 8 May 2012, retrieved from Universiti Malaysia Terengganu's Sea Turtle Research Unit website on 13 May 2012.

- "Leatherback turtle swims from Indonesia to Oregon in epic journey". International Herald Tribune. 8 February 2008. Retrieved 8 February 2008.

- James, M.C.; Davenport, J. & Hays, G.C. (2006). "Expanded Thermal Niche for a Diving Vertebrate: A Leatherback Turtle Diving into Near-Freezing Water". Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology. 335 (2): 221–226. doi:10.1016/j.jembe.2006.03.013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hamann, Mark; Riskas, Kimberly (15 August 2013). "Australian endangered species: Leatherback Turtle". The Conversation. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- Piper, Ross (2007), Extraordinary Animals: An Encyclopedia of Curious and Unusual Animals, Greenwood Press.

- "WWF - Leatherback turtle - Ecology & Habitat". Marine Turtles. World Wide Fund for Nature. 16 February 2007. Archived from the original on 9 August 2007. Retrieved 13 September 2007.

- Mrosovky; Ryan, GD; James, MC; et al. (2009). "Leatherback turtles: The meance of plastic". Marine Pollution Bulletin. 58 (2): 287–289. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2008.10.018. hdl:10214/2014. PMID 19135688.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Calrecycle.ca.gov, California Integrated Waste Management Board.

- Bjorndal; Bolten, Alan B.; Lagueux, Cynthia J.; et al. (1994). "Ingestion of marine debris by juvenile sea turtles in coastal Florida habitats". Marine Pollution Bulletin. 28 (3): 154–158. doi:10.1016/0025-326X(94)90391-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tomas; Guitart, R; Mateo, R; Raga, JA; et al. (2002). "Marine debris ingestion in loggerhead sea turtles, Caretta caretta, from the Western Mediterranean". Marine Pollution Bulletin. 44 (3): 211–216. doi:10.1016/S0025-326X(01)00236-3. PMID 11954737.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bjorndal, K.A. et al., 1997. Foraging Ecology and Nutrition of Sea Turtles. In The Biology of Sea Turtles by Peter L. Lutz and John A. Musick. 218-220.

- "Dermochelys coriacea (Leatherback, Leathery Turtle, Luth, Trunkback Turtle)". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- Department of Environmental Protection (24 October 2006). "DEEP: Leatherback Sea Turtle Fact Sheet". Ct.gov. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- Broadstock, Amelia (31 December 2014). "A Leatherback turtle has been found washed up on Macs Beach, about 6km north of Ardrossan". The Advertiser. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- Fretey J, Babin R (January 1998). "Arthropod succession in leatherback turtle carrion and implications for determination of the postmortem interval" (PDF). Marine Turtle Newsletter. 80: 4–7. Retrieved 15 September 2007.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Caut, S.; Guirlet, E.; Jouquet, P.; Girondot, M. (2006). "Influence of nest location and yolkless eggs on the hatching success of leatherback turtle clutches in French Guiana". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 84 (6): 908–916. doi:10.1139/z06-063.

- Chiang, M. 2003. The plight of the turtle. Science World, 59: 8.

- "Sea Turtle". Seaworld. Archived from the original on 29 May 2013. Retrieved 2 September 2011.

- Ernst, C., J. Lovich, R. Barbour. 1994. Turtles of the United States and Canada. Washington, D.C., USA: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Lee PL, Hays GC (27 April 2004). "Polyandry in a marine turtle: Females make the best of a bad job". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 101 (17): 6530–6535. Bibcode:2004PNAS..101.6530L. doi:10.1073/pnas.0307982101. PMC 404079. PMID 15096623.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fretey J, Girondot M (1989). "Hydrodynamic factors involved in choice of nesting site and time of arrivals of Leatherback in french Guiana". Ninth Annual Workshop on Sea Turtle Conservation and Biology: 227–229. NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-SEFC-232.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rimblot F, Fretey J, Mrosovsky N, Lescure J, Pieau C (1985). "Sexual differentiation as a function of the incubation temperature of eggs in the sea-turtle Dermochelys coriacea (Vandelli, 1761)". Amphibia-Reptilia. 85: 83–92. doi:10.1163/156853885X00218.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Desvages G, Girondot M, Pieau C (1993). "Sensitive stages for the effects of temperature on gonadal aromatase activity in embryos of the marine turtle Dermochelys coriacea". General and Comparative Endocrinology. 92 (1): 54–61. doi:10.1006/gcen.1993.1142. PMID 8262357.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Leatherback Turtle (Dermochelys coriacea)". NOAA. Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- "WWF - Leatherback Turtle - Threats". Marine Turtles. World Wide Fund for Nature. 16 February 2007. Archived from the original on 21 November 2007. Retrieved 11 September 2007.

- Townsend, Hamish (10 February 2007). "Taste for leatherback eggs contributes to Malaysian turtle's demise". Yahoo! Inc. Retrieved 10 February 2007.

- "Jellyfish Gone Wild". NSF. Archived from the original on 12 July 2010. Retrieved 6 June 2013.

- http://www.jellyfishfacts.net/jellyfish-diet.html

- Felger, Richard (1985). People of the Desert and Sea. Arizona: The University of Arizona Press.

- "Grupo Tortuguero Comcaåc". www.oceanrevolution.org. Archived from the original on 20 October 2018. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- Foley, Allen (2017). "Distributions, relative abundances, and mortality factors of sea turtles in Florida during 1980-2014 as determined from strandings". Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission.

- Safina, Carl (2006). Voyage of the Turtle: In Pursuit of the Earth's Last Dinosaur. New York: Henry Holt and Company. pp. 52, 53, 60. ISBN 978-0-8050-8318-7.

- "TURTLE CAUGHT WITH CRAY POT". West Australian (Perth, WA : 1879 - 1954). 3 January 1951. p. 10. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- http://www.edgeofexistence.org/species/leatherback/

- Wallace, B.P.; Tiwari, M.; Girondot, M. (2013). "Dermochelys coriacea (East Pacific Ocean subpopulation)". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2013: e.T46967807A46967809. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013-2.RLTS.T46967807A46967809.en. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- Tiwari, M.; Wallace, B.P.; Girondot, M. (2013). "Dermochelys coriacea (Northeast Indian Ocean subpopulation)". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2013: e.T46967873A46967877. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013-2.RLTS.T46967873A46967877.en. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- The Northwest Atlantic Leatherback Working Group (2019). "Dermochelys coriacea (Northwest Atlantic Ocean subpopulation)". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T46967827A83327767. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-2.RLTS.T46967827A83327767.en. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- Tiwari, M.; Wallace, B.P.; Girondot, M. (2013). "Dermochelys coriacea (Southeast Atlantic Ocean subpopulation)". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2013: e.T46967848A46967852. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013-2.RLTS.T46967848A46967852.en. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- Tiwari, M.; Wallace, B.P.; Girondot, M. (2013). "Dermochelys coriacea (Southwest Atlantic Ocean subpopulation)". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2013: e.T46967838A46967842. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013-2.RLTS.T46967838A46967842.en. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- Wallace, B.P.; Tiwari, M.; Girondot, M. (2013). "Dermochelys coriacea (Southwest Indian Ocean subpopulation)". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2013: e.T46967863A46967866. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013-2.RLTS.T46967863A46967866.en. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- Tiwari, M.; Wallace, B.P.; Girondot, M. (2013). "Dermochelys coriacea (West Pacific Ocean subpopulation)". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2013: e.T46967817A46967821. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013-2.RLTS.T46967817A46967821.en. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- Mast RB, Pritchard PC (2006). "The Top Ten Burning Issues in Global Sea Turtle Conservation". The State of the World's Sea Turtles Report. 1: 13. Retrieved 14 September 2007.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "The Leatherback Trust". The Leatherback Trust. 2007. Archived from the original on 1 November 2007. Retrieved 13 September 2007.

- "The Leatherback Turtle (Dermochelys coriacea)". The Oceanic Resource Foundation. 2005. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 17 September 2007.

- "NOAA designates additional critical habitat for leatherback sea turtles off West Coast". 2012. Retrieved 27 January 2012.

- Doyle, Tom; Jonathan Houghton (2007). "Irish Sea Leatherback Turtle Project". Irish Sea Leatherback Turtle Project. Retrieved 13 September 2007.

- "Earthwatch: Trinidad's Leatherback Sea Turtles".

- "Parismina.com". Save the Turtles. Heather Hjorth. 2009. Retrieved 20 October 2009.

- Cruz, Jerry McKinley (December 2006). "History of the Sea Turtle Project in Parismina". Village of Parismina, Costa Rica - Turtle Project. Parismina Social Club. Retrieved 13 September 2007.

- Zappei, Julia (12 July 2007). "Malaysia mulls cloning rare turtles". Yahoo! News. Retrieved 12 July 2007.

- "Experts meet to help save world's largest turtles". Yahoo! News. 17 July 2007. Retrieved 18 July 2007.

- "Tamar's Bulletin". Projeto Tamar's official website (in Portuguese). December 2007. Archived from the original on 21 December 2007. Retrieved 26 December 2007.

- "UFPR's bulletin". Federal University of Paraná's official website (in Portuguese). January 2010. Retrieved 23 January 2010.

Further reading

- Wood, Roger Conant; Johnson-Gove, Jonnie; Gaffney, Eugene S.; Maley, Kevin F. (1996). "Evolution and phylogeny of the leatherback turtles (Dermochelyidae), with descriptions of new fossil taxa". Chelonian Conservation and Biology. 2: 266–286.